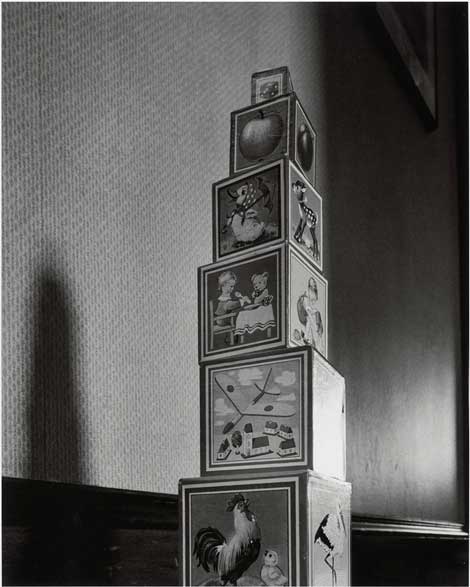

In 1987, the year his son Brady turned two, Abelardo Morell lay down on the nursery floor in order to see the world the way a wriggling baby would. From that vantage point he looked up at a stack of blocks towering over him as if it were a BCE column or stele, and he took a photograph. In 1993 when Brady was six or seven, Morell looked up at a wine glass sitting on the kitchen table, seeing it approximately the way that his son would have then, and saw that the glass full of liquid was acting as a lens. The window beyond it was focused upside down and backwards, bending its frame to the curvature of the glass. So he took another picture. The next year, when he accidentally broke his glasses, snapping the frame in half at the bridge, he set up the two pieces on a table and took a picture of himself focused through the lenses of the broken glasses. In this photograph he sits with his eyes closed, as if dreaming about how the world would look without the usual modern enhancements of vision.

By then, Morell had taken lots of pictures from odd points of view. Trying to look at the world through fresh eyes like this, the way a newborn infant would, led him to wonder whether he couldn’t do the same thing with photography itself–to go back to the earliest kind of camera, before film even existed, and meditate on such imagery in its fleeting, original form. In 1991 he had taken a cardboard box recently emptied of Martini & Rossi bottles and, cutting a hole in the side, gaffer-taped a lens mount over the hole. Presto! When he turned on a light bulb he’d placed outside the box near the lens, an inverted image of the bulb was seen through the open end of the box glowing in the darkened interior. This was his earliest experiment with the camera obscura, a device described by Aristotle, elaborated by Leonardo, and in wide use as a visual aid by the Baroque era.

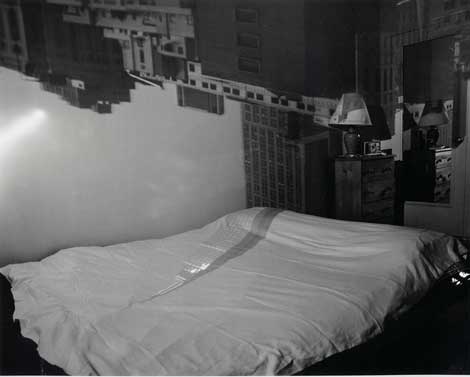

“Camera” means room, of course, and over the last two decades Morell has been turning rooms in hotels or houses where he was staying into a camera obscura. Standing in this original kind of camera behind the other kind, one loaded with film, he then photographs the image he’s projected onto the walls, furniture and whatever else is in the room. Between the confusing relationship of the two kinds of cameras and the fact that the outside view now comes inside, but upside down and backwards, there is a certain hall-of-mirrors effect to the photographs he makes. We are, literally, seeing double. The imagery is usually as beautiful as it is mystifying; it’s a brain teaser that holds our attention because we can’t disentangle its ambiguities. In a room in New York, Morell made the Empire State Building lie down on a day bed as if it were taking a nap, and in Paris he did the same thing with the Eiffel Tower. The dizzying effect of such pictures makes us feel as if we might need to lie down too.

His intention is to recover some of the mystery and power of photography in our digital age, when the image glut issuing from cellphones and online sources has deadened our visual senses. To that end, he works in a disarmingly low-tech way. To turn whatever room he was using into a camera obscura, he would tape black plastic sheeting (garbage bags?) over the windows and then scratch a three-eighths inch hole in this window cover in order to turn the whole room into a pin-hole camera. If the image didn’t fall where he wanted it to in the room, he’d tape up that hole and scratch another somewhere else, until he got the image he wanted. Then he’d set up his view camera so it could photograph the results, an exposure that usually lasted six to eight hours in the room’s dim interior.

In 1997, while he was creating a view of the Tetons, he and his 11-year-old son got in a whole day of hiking while the exposure was being made. The view of the Tetons also shows how Morell likes to play, facetiously, with photographic history. He took down a piece of hotel art on the wall of the room and replaced it with a framed reproduction of a photograph of the Tetons Ansel Adams had made nearby in 1942. Like Morell’s inverted camera obscura view of Adams’ subject, the mass-produced Adams poster and a kitsch figurine of a stag Morell put on a table in the room turn Adams’ view of the world topsy-turvy.

While his work with the camera obscura has been the mainstay of his career, he’s also done other, equally beguiling projects. Among the improbable subjects he has turned into fascinating ones are books. He didn’t use the camera obscura for these images; they are straight-forward film-camera photographs of the subject. But the magic and mystery comes from the way he arranges the books he photographs. A page in a book is of course a two-dimensional object that enables us, through reading, to imagine a three-dimensional world. But Morell’s gambit is to make the books and the stories they tell three-dimensional.

A copy of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland that’s sitting on edge with its pages fanned out, for instance, is opened to a quite malevolent-looking picture of Alice ( one of John Tenniel’s woodblock illustrations for the first edition). In Morell’s photograph, she is watching a cut-out of the White Rabbit as he, having escaped the book, tries to tiptoe past the fan of pages, from which Alice’s scary hand reaches out to grab him. In another photograph, a medieval astronomer looking through his telescope in a book lying open on a table appears to stare at the starry heavens seen in a book standing on edge above him. An ancient grandfather clock is beside him. In Morell’s composition, the dimension of time intersects with the dimension of space. Again, Morell takes something silly, a conceit—child’s play—and makes a metaphysical conundrum of it.

All of these examples and lots more are in the traveling exhibition Abelardo Morell; the Universe Next Door, which was organized by Elizabeth Siegel, a curator of photography at the Art Institute of Chicago, where the exhibition was on view last summer before coming to the J. Paul Getty Museum in the fall. It closed at the Getty this past January and opened at the High Museum of Art in Atlanta, its final venue in February. Even if you missed the exhibition in Chicago or LA, you can still be dazzled by Morell’s work in the catalog where most of the images are beautifully reproduced.

Morell’s most recent work is with a new, old optical device, the tent camera. This is a light-tight tent that has a periscope sticking up through the top of it. It was yet another drawing aid, for the mirror at 45 degrees in the periscope projected the scene outside onto a piece of drawing paper on a horizontal surface inside the tent. Morell’s innovation with this device is to project the image onto the ground and make a photograph of it there, atomized by gravel or gridded by paving stones or laid down on the dirty strips of a tarpaper roof. Thus does the eruption of Old Faithful look like a volcano rather than a geyser. Some of these images are also a commentary on the history of photographic and other visual arts. In Yosemite National Park, Morell made two tent-camera images by following in the footsteps of 19th-century photographer Carleton Watkins, and he did a view of the sea from the backyard of Winslow Homer. His most recent project is a commission to produce views of Toledo, Spain, in order to commemorate the death there of El Greco 400 years ago.

Among the views Morell has made, those done on a trip to Cuba in 2002 may have a special poignancy for him. It was the first time he had been back since his parents had decided to leave Cuba in 1962, after the Bay of Pigs invasion but before the missile crisis. Life in New York must have been a shock after having lived in a small coastal village in Cuba. In New York, his father, who had been in the Cuban navy during the Battista era, became a building superintendent, a job that included a basement apartment for his family. Throughout his subterranean teens Morell was only able to see “the world outside through a single, street-level window,” as the curator Diana Gaston put it. Perhaps it’s not surprising that, having spent his formative years trapped in Plato’s Cave, Morell should be spending his adult years looking over and over again for a room with a view.

All images Courtesy Edwynn Houk Gallery/New York