Your cart is currently empty!

Byline: Ezrha Jean Black

-

High Anxiety: A Conversation with Karen Finley

I have an ongoing conversation with Karen Finley that operates on several levels, one of which is simply her public conversation; i.e., the level on which her work has made its enduring imprint on the culture and more specifically the phenomenon of cultural trauma.

Our “live” conversation has been going on since 2015, around the time of her The Jackie Look performances in LA and the companion “Love Field” gallery show, in which she broke down the “Jackie” narrative—the discrete layers of trauma bound up in the interwoven narratives of Jacqueline Onassis’ lives—into its most resonant incidents, performances, props and gestures.

There’s an interesting resonance to her work right now in that, for many of us, the last four years have been a period of unbroken cultural trauma, magnified by an unparalleled political trauma and an environmental trauma without precedent afflicting the entire planet. The Covid-19 pandemic and attendant shutdowns in New York, California and points between have given an additional dimension to her projects as her interactions in the public sphere have migrated to electronic screens and cell phones.

Not unlike a billion or so of my fellow earthlings, I have an off-again, on-again relationship with social media. Off Facebook (mostly), and on Facebook-controlled (alas) Instagram. Although Finley is most celebrated for her performance work, the often stark pictogramic imagery that has often accompanied her published transcriptions and parable-like narratives and prose-poems, summarizing their deep psychological and cultural deconstructions, continue to show up on her own Instagram feed.

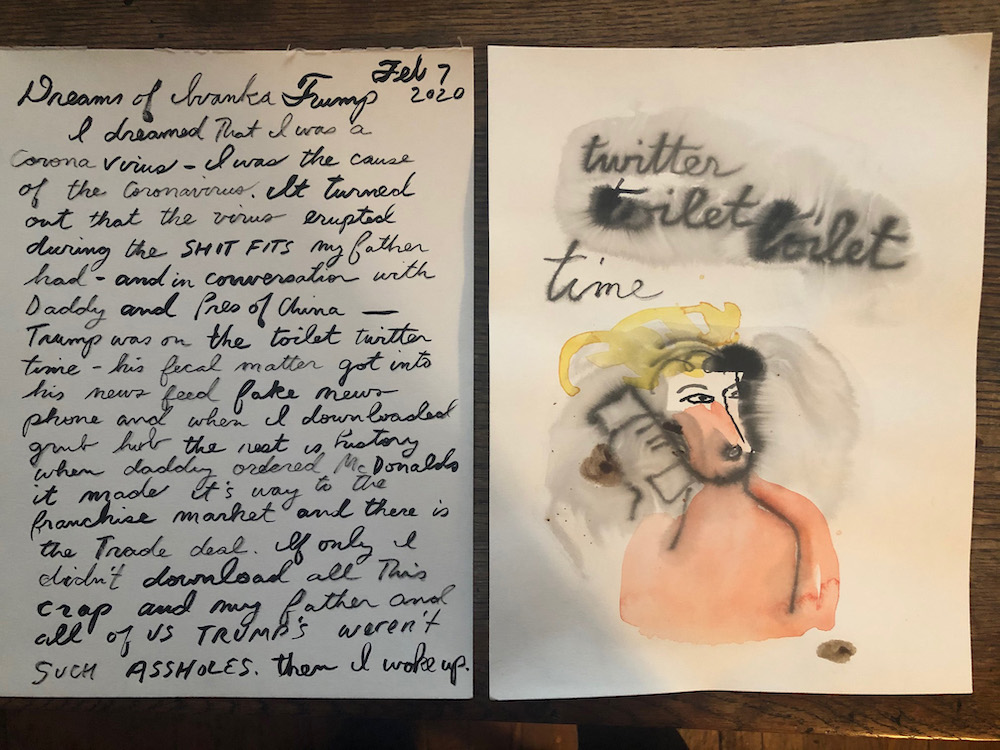

Not long before CV-19 hit New York like a cyclone, she had a series of drawings, entitled “The Dreams of Ivanka Trump,” that seemed to feed off the energy from her 2019 “Sext Me If You Can” series. But sometime around the vernal equinox, the feed abruptly shifted to word drawings in watercolor or pen and ink that placed a single word, sometimes burnished with color or a coppery gold, in a shadowy gray, miasmic field: Covid, mask, corona, quarantine; and so forth. These gradually gave way to short phrases, often laid out on printed pages—pages ripped from old poetry anthologies, children’s storybook pages, calendars, cookbook recipes, advertising, flash cards, sheet music—which might sardonically emphasize or ironize the word or intention behind it. More often, though, the message has been pretty direct: Scrawled vertically across a telephone message pad in one such post (with each message slip marked [To] ‘Trump’/[From] ‘Fauci’ (and signed by ‘Pence’): SHUT / THE / FUCK / UP.

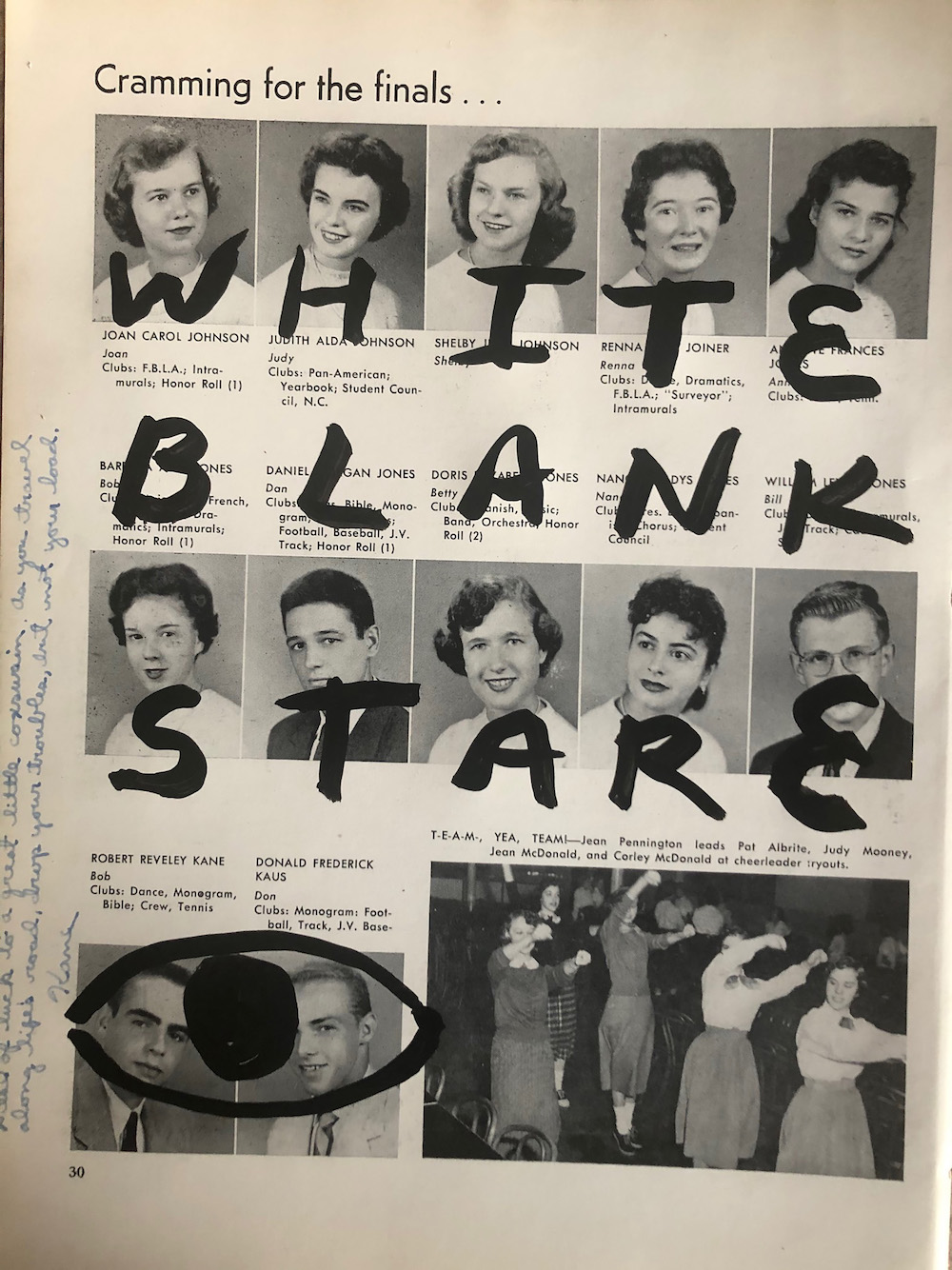

There are shifts in the feed that reflect the mood or the moment, the events pressing in on all of us—though they can sometimes take us by surprise. As with almost anything that shows up on one’s mobile device, much depends upon when the image is viewed. Awakening to Finley’s IG post, White Blank Stare (2020) after some days away from my last digital encounter, I found myself sorting through the trauma of youthful repression underlying my default resting bitch persona, rather than the unconscious white privilege the image (at second glance) clearly addressed. It was at some point into my second cup of coffee (and laughing at myself), I decided it was time to catch up with Karen Finley.

It was more than a month later, not long after the Republican National Convention, when we finally caught up via (what else?) Zoom. After a bit of my own contextualizing, and the recent context of her Instagram (by way of Michelle Obama: “It is what it is.”), we picked up where we left off.

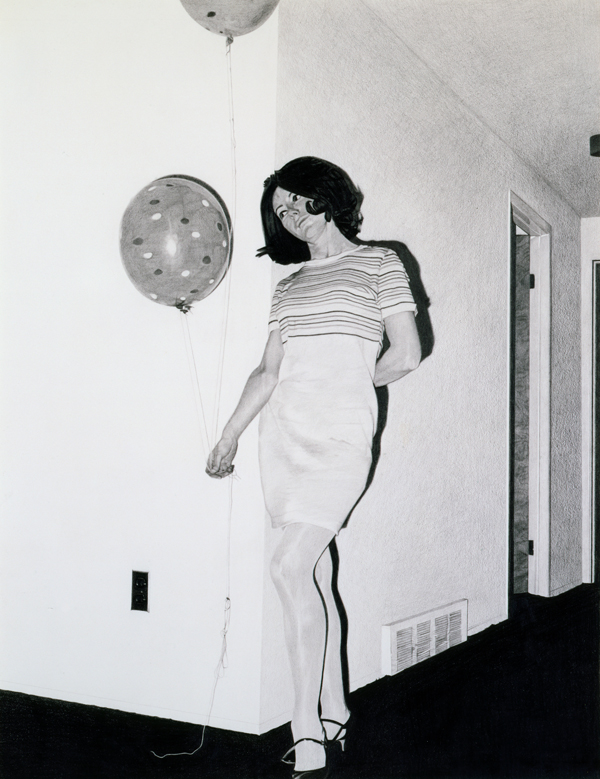

Jackie at the Biltmore, The Jackie Look performance series, 2015, photo by Violet Overn. Ezrha Jean Black: So where are we now? Where are you now?

Karen Finley: I think that’s what we’re all kind of asking ourselves. I have a double consciousness of where we are now. I have the day-to-day living of just experiencing what we’re all going through under the pandemic and through the regime of Trump, and the day-to-day realities of what is happening in ways I’ve never experienced in my life: with the pandemic, with the protests. Although I did grow up with protest, looking at the extreme violence coming from the leadership, from the White House, the authoritarian rule with the continuing lies—yes, I lived through Nixon, the FBI, the police state we’re all aware of; but in this moment, we’re in desperate times. Yet I am inspired by what has been happening with the protests. And since I’m not able to be putting a lot of my energy into performing, the urgency is invested in the response I create with my artwork. I’m responding from a kind of social critic’s perspective, but also narrowing it down to something very specific. It’s an artist’s perspective as kind of a historical recorder of the times we’re living in. It looks quick and spontaneous, but it does take a certain amount of thought and practice in getting it—to look at the idea, to manipulate the subtexts, so I’m layering it over images in terms of the political work. Or even, let’s say, what I was doing today, which came out of the conversation we were just texting each other about, thinking about the RNC and looking at the portrayals, the costuming, the gender presentation for the Trump women—which almost went to the level of a costume horror show. All of the women had this Night of the Living Dead or Frankenstein kind of look with the black eyeliner; and with Melania, her eyes set back to such an extent. They looked like something out of the Addams Family—and that had comedy in it—but it almost looks like Morticia.That might be giving them too much credit.

It’s like a horror show. And I was thinking of this idea of the Dark Shadows, the Trump Shadows. So that’s what I wanted to be doing today. I think they really are projecting a kind of horror family, the monsters that they are. There was a sense of monstrosity in the way that they presented themselves Thursday night. Besides their action now, that you really see …who was the Trump girlfriend who spoke?

Nightmares of Ivanka 2, 2020 You must be referring to Kimberly Guilfoyle. Yeah—she was something!

[Then ensued a brief deconstruction of the Guilfoyle Evita/Bananas/The Maids performance.] And also Melania had that khaki-green outfit she was wearing—it was like military garb.The whole thing looked a bit militarized. And of course she had to mow down half the Rose Garden to be a better backdrop for her new military look.

It looked like it was absent of nature, like they’d removed it.Well they removed that entire row of crabapple trees.

[We then thrashed out the Melania-Ivanka psychological dynamics for a minute or so, while we practiced shade-throwing eye rolls.]It’s horrific; and I’m so concerned about taking this situation and making art out of it. What are these borders of art as an escape, an entertainment, as this space within which it’s palatable to be creating this work; where it’s decorative—what are those places?

But I’m just interested in hosting it. I’ve been doing much more work than that. But I don’t want to put everything on [Instagram].

But there’s a consistent through line. It’s not a gesture, it’s not simply a word. You’re really deconstructing it, following every implication of the word, gesture, image—breaking it down, exploring it at the most basic psychosexual level—and I think you have to go there, because what we’re addressing here is this kind of authoritarianism that has never been so nakedly exposed. Certainly not like this—in lights, against the most officially sanctioned stage in the world.

I’m not necessarily doing it to be converting people, but I’m trying to offer a way of taking a deeper look—to do what art does. I feel that’s part of my job as an artist, and I take that job seriously. Can I say that it’s part of my artistic service? And because I’m not able to be performing—it’s not about performing for the camera, my voice—I’m not interested in putting me in there. It’s about what I’m inspired to be doing now within the visual work right now.I will say that I look at these things as once upon a time I looked at the drawings, sketches in the book versions [of collected performance work]. In that I can see performance coming from this. In that it goes from a word to a phrase to a kind of poetic fragment, to a kind of chant, or incantation, through to fully fledged performance. You know how to evolve these things.

I think that has always been part of what my creative response has been.I was just recently speaking with the choreographer Miguel Gutierrez about the NEA (he’s doing a series of podcasts—so I had to re-live that period again) and thinking about artists’ responses in the 1990s. What seems to have happened in a strange way is that more young people are adapting methods we were developing then. So it’s more familiar, easier for me, for them to be doing it. So there’s a lot of incredibly interesting work going on right now, and I’m inspired by it.

[Finley singled out two other artists—Amy Khoshbin and John Sims—and we discussed their work briefly.]

So that‘s the contrast—between the familiarity, the politics of the times—whether you go back to the 1960s, 1970s, 1990s, Vietnam war, Iraq war, the Civil Rights Movement—and the art and response coming out of it. I’m not surprised. I mean I’m devastated. But there’s a familiarity. The latest [performance] work I’ve been developing over the last two years was about a certain paralyzing trauma I see being acted out—sometimes by people you know or are acquainted with. They behave as if they were in agony, traumatized, can’t leave their houses—just refusing to look at what’s happening. They can’t believe what they’re seeing in the news and are completely paralyzed by it. And I find that’s just such a form of whiteness. I mean, where were they? ‘Where were you during the Reagan years?’ Or, looking at the Bushes—getting us into the [Iraq] war. Or thinking about the FBI and everything that they have done to so many people, from the Black Panthers to protesters. You want to see a horrible time? That was horror. People get almost nostalgic. People saying, ‘Oh my god, I miss the Bushes; I miss Laura so much.’

[This stops me dead in my tracks for a split second. ]

Karen Finley, photo by Midge Wattle. Wait—but these aren’t really pals, people you know.

No, but they’re people that you can see, who have the sense that this time, what’s happening now, has never happened before. I think this is a feeling you see in different places throughout America.Because there was the veneer of civility that, thanks to people like Stephen Miller and Steve Bannon, has suddenly been violently ripped away. The veneer that masked the actuality of, maybe not kids in cages, but black mass incarceration—a reality, an ongoing reality. There’s no dressing it up.

But it could also be part of my denial, too. I mean it is a horrible time, so you have to watch out for this sense of, ‘Oh it’s been like this before’—that’s a kind of denial, too; you have to focus the determination to make sure that there’s accountability. And I do have a real fear, with this election, of it becoming more authoritarian—I have real fears about the election. There is a real difference between having him [Trump] in that office, that regime, and Biden and Harris. And I’m aware of their histories.[We briefly discuss their political, prosecutorial histories here.]

Both of them. I’m rolling my eyes here—like Melania!

Yes, both of them. And Anita Hill—there’s a lot there.And there was a lot more there; and we carried it forward a bit, from politics, to climate change, anxiety—and the humor and perspective we use to pull ourselves through it.

While Finley’s next print and performance works are still in development, her Instagram feed continues: @the_yam_mam—a must for this new-old age of anxiety.

-

Deep Listening By the Light of a “Full Pink Moon”: Opera Povera in Quarantine

The planet, some of us might say, is having a moment. Panic, collapse, disruption—with the tables turned on the principal disrupting species by an errant configuration of protein presumably just doing its thing in the carbon cycle; also course-correction, regrouping, re-orientation, re-alignment. And—also for a change—this might not simply be a function of human projection. As the carbon cycles run their variable course in the biosphere, the planet moves in its own time-space relationship with planets, the nearest stars, and not least of all, its satellite, the moon. These are cycles that can be neither denied nor disrupted for the simple fact that they are unlikely to be resisted by any living thing, even those on the ocean floor.

Whether musicians might be more susceptible to such natural rhythms is a thesis that can’t be proven; but the late composer and theorist, Pauline Oliveros, would almost certainly have embraced the notion of cultivating awareness and sensitivity to environmental rhythm, sound and vibrations. What she and others referred to as “deep listening” or “sonic awareness” were at the core of her artistic practice. From an environmentally engaged approach to listening, composing and making music that ranged from spelunking to the furthest edges of electronic music to pure meditative silence, Oliveros shaped her work by in effect sounding it out peripatetically amid collaborators, musicians, audiences transformed into participants, and the moment itself.

Sean Griffin, the director of Opera Povera, no less than Oliveros herself was, is alive to such moments; and as the moon moved towards its near-perigee alignment with Venus and Mercury that terrestrials refer to, more wishfully than accurately, as the “Pink Moon”—perhaps more wishful than ever, as most of us are nearly frozen in isolation from one another—Griffin seized on the idea of executing Oliveros’ The Lunar Opera: Deep Listening For_Tunes, as if in reverse: instead of simply pulling all of the performers and participants through internet and telecommunications to a single place (the original locus was Manhattan’s Lincoln Center), why not make the cloud in effect the actual platform, convening participants and performers by video-conferencing tools (Zoom) into a live-streamed virtual locus that would unfold as the moon appeared and began its ascent relative to the earth.

“We wanted to open it up to the world. Instead of creating an elaborate imagined city, we could have a series of actions that that we would do together, sonic monuments projecting our good will out to each other.”

His near-random idea (Oliveros would have loved the spontaneity) took shape as he chatted with his CalArts colleague and frequent collaborator, violinist Madeline Falcone, who, along with Nick Norton, rallied to help co-organize the Equal Sound Corona Relief Fund to provide emergency financial relief for musicians who suddenly found themselves without work, contracts, or engagements effectively for an entire season or longer. As the word filtered out via social media, musicians emerged from all corners of the world to participate. Some of the names will be instantly familiar to new music fans both in Los Angeles and world-wide: George Lewis, Anne LeBaron, Max Richter, Carmina Escobar, Midori, Christine Tavolaci, and on—a list 250 names and growing (including many performance and multi-disciplinary artists—Cassils, Nao Bustamante and Susan Silton were just three of the names that jumped out at me).

This will be Falcone’s eighth project with Griffin. They came together in 2013. Falcone, whose Isaura Quartet collaborated with Griffin on two of his 2015 Opera Povera presentations at the Schindler House in West Hollywood—the Charles Gaines Declaration on the Rights of Women from Manifestos 2, and George Lewis’s 2007 Unison, last worked together with Ron Athey in Griffin’s production of Athey’s Gifts of the Spirit – a ritualized setting of the automatic writing ‘seances’ Athey has been conducting/performing for some years now.

For this collaboration, though, Falcone will be producing, working alongside the production’s technical director, Sagan West Fylak. “Two of us are going to be at CalArts, where we’ll be running the live feed from a set-up performance area. There will be a lot going on…. It will be chaos at times. Each performer will be able to experience all the performers in the Zoom meeting. The performers will be free to duet with another available musician; and performers can use the chat function to chat with one another. We want this to be a participatory event.”

Griffin elaborates: “This is why I knew the score would work so well. It’s an algorithmic score for large crowds of people: performers listen from where they are for a cue to perform; then when they hear the cue again, they pause, and wait for the cue to happen again.

“Everyone generates his or her own characters. In one passage, everyone will come together to blast out as much noise as they can in different directions. Then there will be a ten-minute passage of complete silence; and another where we’re trying to tune into, mix into each other.

“I have to reinforce that this is a participation opera, and best viewed from inside the opera. The openness of the score is evidence of Pauline’s trust in her fellow artists to create something out of these descriptions which are basically relationships, using that as a compositional device.”

Griffin has some hands-on experience with this kind of material. One of his Schindler House presentations was a treatment of Oliveros’ landmark 1970 To Valerie Solanas and Marilyn Monroe in Recognition of Their Desperation.

As they move through—and actually conduct—the chaos, Griffin and Falcone are making room for music or other performance elements that may or may not always mesh with the stream coherently for the rest of the participant-audience. “There will be rooms for participants and small breakout rooms that will not be live-streamed in the international feed.” Griffin mentions costume changes, a “documentation collage.” Falcone independently clarifies, “We will select other sections to feature at our end. We’ll be collecting documentation to be edited afterwards.”

Once again, Griffin and Falcone will be working with Ron Athey, which seems to promise that the essential element of Druid ritual will be working its lunar magic.

The performance begins at 6:00 p.m. PDT (and through to at least midnight); with a pre-concert conversation including Griffin, Athey, George Lewis, and others set to commence at 5:00 p.m. PDT.

Although it’s hard to predict how a net cast as far and wide as this one—with participants everywhere from the California coast to New York to Germany and even Australia—Griffin indicated that a test last Friday night that included at least 66 participants went well. Griffin signs off with an isolation-breaking note, reminding me that “when we look up at the sky no matter where we are, we’re looking at the same world together that night.”

Full Pink Moon streams live beginning at 6:00 p.m. (with pre-concert conversation at 5:00 p.m.) on Twitch, YouTube, FacebookLive and at seangriffin.org/full-pink-moon/livestream. Contributions may be made to the Equal Sound Corona Relief Fund by going to the Equal Sound website.

-

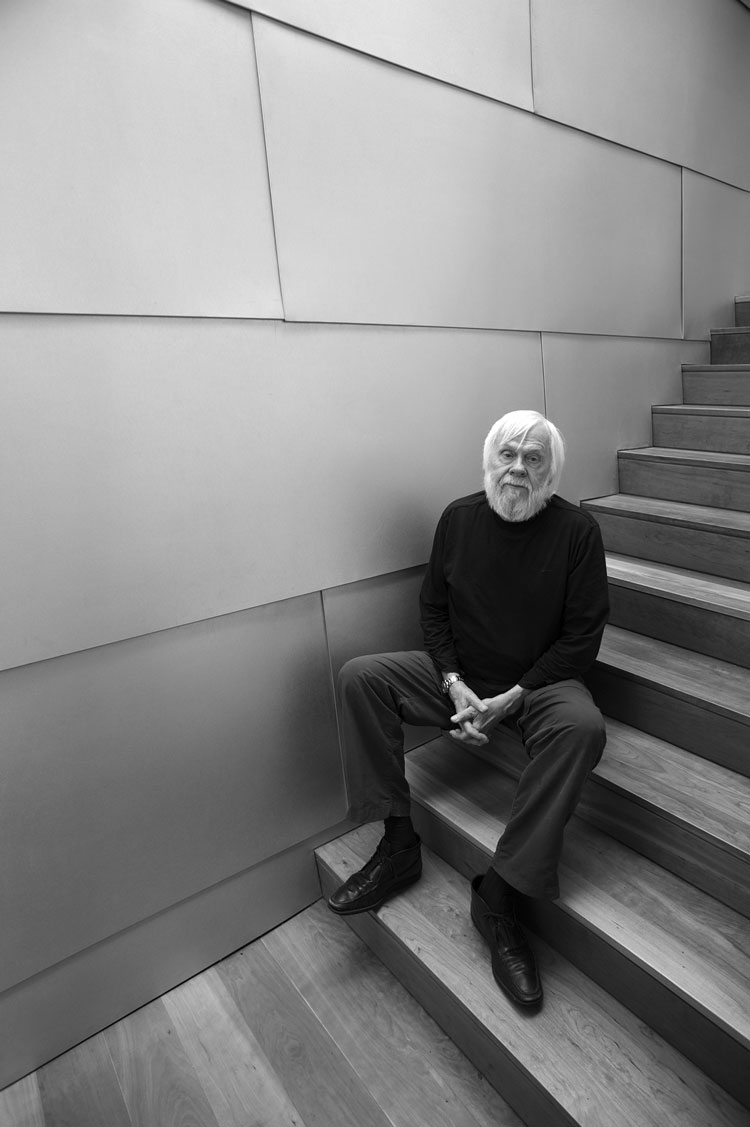

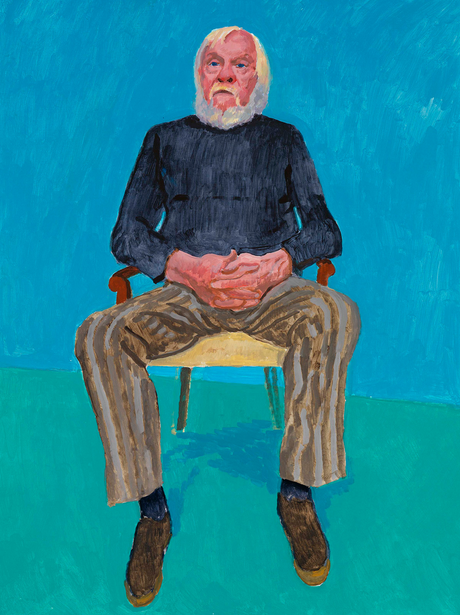

Saying Goodbye to the Godfather: John Baldessari (1931–2020)

I learned yesterday—along with most of the Los Angeles art world –that John Baldessari had died. (He had actually died Thursday, but the word filtered out only this week-end.) Long before I knew him or what he represented (not only in Los Angeles, but the world), and long before I wrote about fine arts in Los Angeles, I would see him frequently at art gallery openings. (I always had many artist friends; and in Los Angeles it was easy to fall into the habit of keeping an eye open for developments on that front.) There were odd jags when I would see him at several in a row, often in the same evening.

You couldn’t miss him. He was almost always the tallest man in the room and, even in his minimalist, pared down artist/teacher’s style of dress (usually a simple T-shirt or sweater and jeans), the most distinctive—with his thatch of white hair fringing his forehead and short white beard; and everyone seemed to know him. In other words, even before I knew him as the godfather of L.A. conceptualism, he was clearly the godfather of at least half the L.A. art world. He was by that time already quite famous – though it seemed as much by association with other artists as by his own work, some of which was already the stuff of legend. Even then, the scope of his influence hadn’t quite hit me.

The ‘legend’ finally saw ‘print’ in his hometown not long thereafter with his 1990 mid-career retrospective at MOCA; and it was probably only then that I began to ‘connect the dots.’ It was certainly the first time I began to fully contextualize his place in the larger art world (though even then I did not grasp the global reach of his influence). This was a way different kind of ‘cool’: cerebral but grounded; distilled more than abstracted; and informed by the entirety of actual and variously filtered or mediated experience. It seemed immaterial to me at the time that he had abandoned painting, or what might be considered traditional art media and the notion of hand facture.

John Baldessari, photo by Tyler Hubby. But this abandonment was more than a mere gesture, in a post-Duchamp, post-Warhol sense. In retrospect it seems of a piece with his work in other media—not simply the text paintings, though they certainly presaged it, but the later ‘commissioned’ paintings (with their pointing fingers), and the early photographic series that played on visual syntax, rhyming, conjunctions and disjunctions—works which reached a kind of zenith in his works with film noir stills. His insight into the syntax of commercial narrative was uncanny. No one understood cut, composition, and dissolve like Baldessari (with a few possible exceptions, e.g., Godard). But Baldessari was moving towards a kind of metacritical art—preoccupied no longer with composition, but with the notion of composition; not time, but the notion of time (naturally using art itself—e.g., his proto-canon of contemporary art history). He was moving beyond Conceptualism before he was even through with it.

I had the opportunity to interview him for ARTILLERY in 2010 in conjunction with the Tate Modern-LACMA exhibition, Pure Beauty. By that time I knew him slightly; but Baldessari was not exactly an easy interview. Still he managed to be thoughtful and good-humored about the whole thing. (I was able to tease him about his then dismissal of art-fashion collaborations only a few years later when I saw him at Gemini G.E.L.—not long after he had executed a project for Saint Laurent—which he again took with good humor.) I took some issue at the time with his resurrection of that old chestnut from his text paintings for the show’s title. At that moment (only a decade ago?), it seemed disingenuous and almost simplistic. Now in 2020, it makes a kind of circle-game sense: not a pure beauty—after all, he saw the language of images in the fullness of their simultaneous humor and horror—but a beauty of the pure. Baldessari was after that kind of reduction, a kind of DNA of visual art, and perhaps the sublime itself. And in true Baldessari fashion, he wanted us to reconceive our notion of the sublime—a 100-proof distillation that might soothe and burn, dazzle and terrify all at once.

-

UCLA’s Kristy Edmunds’ Tour de Force

Kristy Edmunds took over the reins of performing arts at UCLA at a time (2010–11) when the kind of avant-garde international theater and festival programming it was famous for seemed to be all but dropping from UCLA’s sightlines. But Edmunds’ purpose and seriousness were conveyed in the rebranding alone: the Center for the Art of Performance (“CAP” UCLA). Within a year, we had a treatment of the work of Jun’ichiro Tanizaki by Complicité, Peter Brook and the Théâtre des Bouffes du Nord, a raft of new music, and a reunion of Robert Wilson, Philip Glass and Lucinda Childs; and Edmunds was just getting started.

Edmunds went on to make CAP UCLA a case study in how to transform an arts institution, and how to bond it to the artists and the community it serves. In essence, she has done that by taking an artist’s approach to programming by transforming the creative and curatorial process to them.

Pam Tanowitz, Four Quartets. Photo: Maria Baranova. Another of her achievements has been a major expansion of CAP UCLA’s physical presence beyond the UCLA campus into the Village and across town at the ACE Hotel, which is more or less where our conversation began.

The decision to expand CAP’s programming to alternative spaces was deliberate, Edmunds confirms. “I began to understand the extraordinary complexity of traffic and logistics and also the changing demographics: where artists are moving, the cultural enclaves and pockets of folks on the East Side… If people can’t get to us with the frequency they desire, can I find the vehicles that will bring the work closer to them? So the ACE partnership was one of those things. Moving a third of our programming into the downtown area was really about creating another point of access for the artists and the work and the communities.”

It is a complex equation, a kind of choreography, to connect these worlds. In another part of our conversation, Edmunds summed up the creative aspect of her role in that equation: “We have to have as much lithe and nimble erudition as an artist will to put the work in the context in which it’s going to mean the most.”

Jerome Bel, Gala. Photo: Josefina Tommasi Audiences are seeing the evolution, and elevation in the standard and their own expectations, and the sense of what is driving this endeavor: a commitment to work across any number of media in pursuit of original ideas, forms and ways of thinking about and making sense of the contemporary world. Edmunds is fully committed to creating the conditions essential to achieving an artist’s vision and bringing the project forward.

“Every single dialogue and discussion with artists means I’m going to eventually end up on a pretty bespoke journey with them,” she explains. “If upholding the integrity of their vision as it’s evolving is part of the practice that I hold, then staying close to what those ideas are matters a great deal. It’s not just transactional.”

When asked if she shapes the programming with the intention of building community, Edmunds affirms, “Absolutely. It’s about what is the role of an artist in cultures across the world and inside a city of this size that the whole world lives in—either temporarily or permanently. For me it’s been about how I program in a way that is taking the artists with an extraordinary generosity of vision that they’re willing to put in front of the questions of our time and the questions they have with their art form, and to give it as much context for an audience as I can, so that they get… not just, ‘do I like the work, thumbs-up or down?’—but: Who is this maker, and in what conditions are they making? And why would they go to such extraordinary lengths to call our attention to something that might be less familiar, and certainly disruptive of the status quo, in order to open us to be awake to the world differently?”

Kristy Edmunds. Photo: Thomas Wasper. For all her breadth and commitment to the fresh and unfamiliar and nurturing the formal evolution of performing artists, she is careful to place some distance between her own enthusiasms and institutional prerogatives. “The worst thing I can do is privilege my personal aesthetic preferences,” she says. “If I condition people to respond to work that I like, then I’m denying the role and responsibility of an institutional practice. I have to be able to connect people to what is going to have integrity and meaning for them, with these artists in these specific sets of conditions—so that everyone can thrive together.”

Edmunds’ process involves helping artists shape their work, and bringing it to CAP UCLA’s various stages and alternative spaces. At any given time, Edmunds is conducting about 300 active conversations with artists, managers, producers and agents. Out of these, the CAP budget will expand to do 45 to 55 projects over a given set of years.

“But that’s probably about the amount an institution is going to be able to mind-share with an audience that’s already over-worked, overtaxed, over-stressed can even handle anyway!” she adds.“So I try to drill as deeply as I can in the principal art forms we’re focused on, and that tends to be five or six [major] productions or concerts a year. And then there are the areas that are signaling where artists are going—interdisciplinary collaborations or projects that are not squarely dance or choreography but might involve visual artist collaborations or a very unique way that a composer is addressing a cultural question in their work, and so forth.”

Taylor Mac, A 24 Decade History of Popular Music, Decades 13 thru 18 (1956-2016) Beyond the daunting difficulties in staging large productions in Los Angeles, are the many problems in facilitating the movement of international elements.

“There’s a lot of reshuffling that goes on… I constantly feel as if I’m in an air traffic control station, seeing which planes can land and with what magnitude,” she says. “Which ones have to keep circling? In the complexity of humanity, there’s almost one project that’s programmed into the season; and then life happens… and it can’t happen. But there’s something real about that, too. When I have to tell our audiences that a project has to be postponed, it’s not like they see it as institutional failure. The reality is people understand now. When I think of the number of artists and practitioners who actually land and arrive here, or are local—our fellows—and have managed to be able to pull residency, creative development with us, find form and get that work on stage, it’s gobsmacking.”

In the last season, such artists included Jérôme Bel (“Gala”), Meredith Monk (“Cellular Songs”—which made for a kind of prelude to Yuval Sharon’s LA Phil production of her “Atlas”), Merce Cunningham (“Night of 100 Solos”) and Nico Muhly (a deep dive into the music of Philip Glass). Kaija Saariaho returns this season (collaborating in a multi-media production of Eliot’s Four Quartets), as does Jean-Claude Barrière, alongside Toshi Reagon’s musical treatment of Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower, and Michael Keegan-Dolan’s fantastical Nordic-Irish reincarnation of Swan Lake, among too many others to recite here.

Michael Keegan-Dolan, Swan Lake. Photo: Colm Hogan. The reverberations of last season seem to flow forward and back from Taylor Mac’s four night/24 decade ‘moment’ (A 24-Decade History of Popular Music). Revisiting that triumph, Edmunds conveys a sense of how she builds the connections between the artists and the audiences for an institution. “I look for where an artist making theater or choreography or whatever form—in order to add some authentic perspective—is bypassing the conventions they already know to allow an audience to be provoked to actually be more emotionally available to seeing something from a different angle, as opposed to the perceived security of going along with the conventional route or wisdom. Building a framework of an audience’s belonging, coming in and out of an institution, is asking people to remember that value proposition: that artists are not here to merely decorate our stages or reinforce our complacency. They’re provoking us to being awake differently and to use more of ourselves towards what they’re thinking about. If the performances are extraordinary, we will go there.”

-

As Is: : Roy Dowell

Roy Dowell seems to be forever attempting to reconcile physical actualities or their aftermaths with moments of apprehension or anticipation, agents or instrumentalities with their symbolic equivalents. Collage is his medium par excellence, but in recent years, his work has moved towards painting unaccompanied by (or simply paraphrasing) collage.

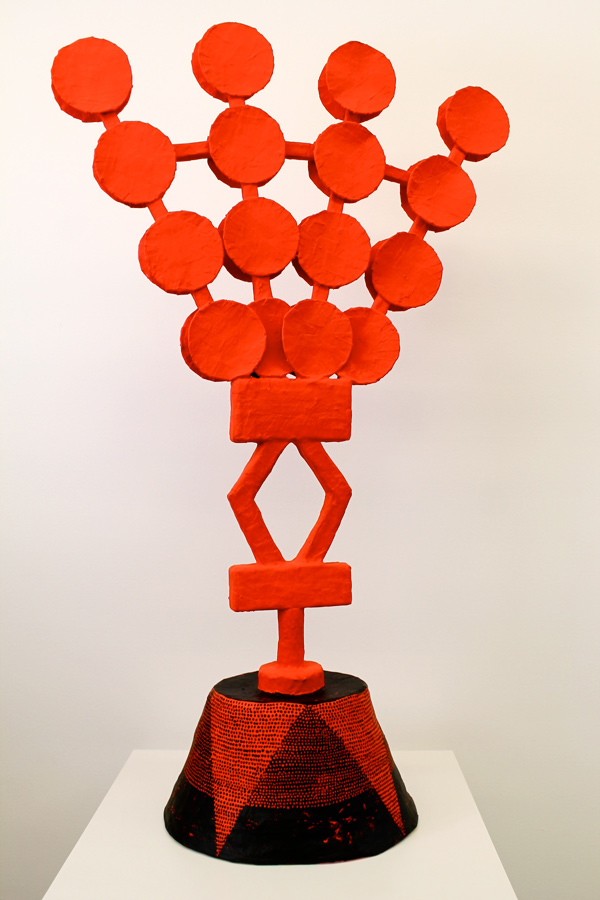

The springboard for the series of new and recent works at As Is may be the single sculpture exhibited here—an untitled (#1054) work of 2014. Resembling a blood-orange totem from ancient or colonial sub-Saharan Africa, it might be a diadem crowned figure; or the diadem itself, or better still, a kind of rattle or noisemaker.

Roy Dowell, Untitled #1054 (2014), 40 x 25 x 13 inches, cardboard, paper and vinyl paint. Courtesy of the artist and As Is. A spirit of play dances with earthbound practicalities in these paintings. Their “devices”—wheels, propellers, rings that sort themselves into circuits, gears and diodes, compasses—are just that; but also toys. But the play is ceremonial—the elements abstracted into totem or heraldic device.

And there’s something more that crosses over into a more ambiguous domain. In several of the linen panels, the lower section is set off with a small round circle at its center. With the paintings’ emphasis on the directional, it might reference the panel of a birdhouse or dovecote, or something larger, however dwarfed in scale; e.g., our own blue orb—registered effectively by its absence; the earthbound contemplating their devices, symbols, cosmology. Or conceivably the reverse: the scope, peephole or camera.

Roy Dowell, Untitled #1123 (2019), 48 x 36 inches, vinyl on linen. Courtesy of the artist and As Is. Untitled #1123 (2019) might be the most heavily freighted with its lower section blue peephole, but dominated by its golden compass that is more like a transparency over a sun-dappled canopy of foliage. Set into a flame-red field with rays extending to its perimeter and criss-crossing ribbons of sky, “moons” float between compass points while bright red arrows push into the corners.

Only four other of the 17 paintings on linen are similarly composed. Others veer closer to the sculptural subject; e.g., Untitled #1117, with its striated gray background that looks like a piece of corrugated sheet metal. Dowell teases the materials here: vinyl color here rendering sequential red mazes of circumscribed rectangles, a soccer ball “wheel” cut out of red and blue hexagons that in turn supports a flipped tower of power conductors against a gorgeous orange trapezoid.

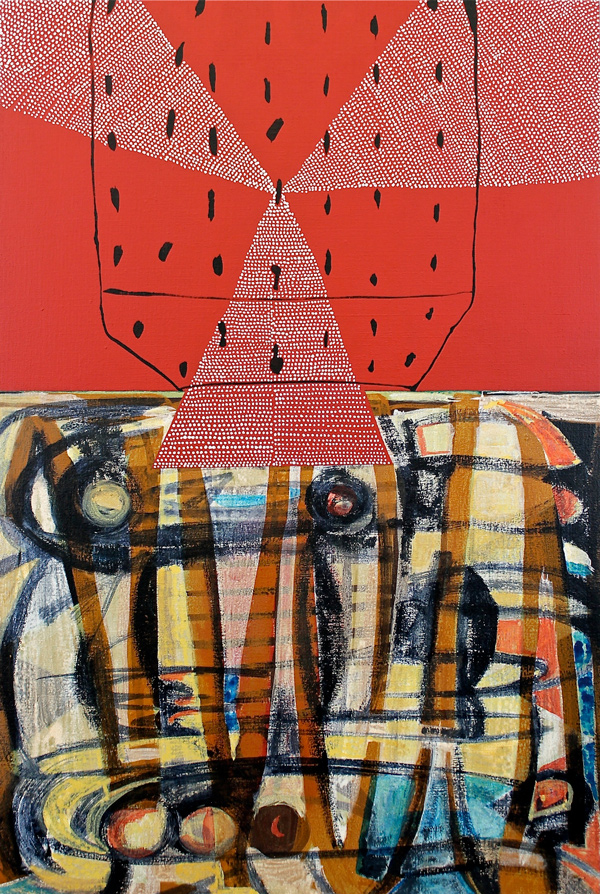

Roy Dowell, Untitled #1117 (2018), 20 x 12 inches, vinyl on linen. Courtesy of the artist and As Is. He’s teasing the viewer, too. The collaged aspect of some of the paintings is almost flippant. Consider the sienna-red and white dotted triangles set against a bisected sienna panel and a doodle-ish wash of desert colors in #1083 (2015). Yet the warning signs are there: a ‘propeller’ might read here as a radiation hazard sign. Dowell’s symbolism goes from the fanciful to the mechanical to the mathematical.

Roy Dowell, Untitled #1083 (2015), 36 x 24 inches, vinyl on linen. Courtesy of the artist and As Is. Less preoccupied with internal conversations or visual rhymes, these paintings invite us to see what this intersection of the instrumental and situational looks like reversed or upside down. Dowell seems to acknowledge that at the moment we’re pulled apart in all directions; but perhaps it’s still possible to find one’s true north.

Roy Dowell, “New and Recent Paintings (and a Sculpture),” April 28 – June 8, 2019, at As Is, 1133 Venice Blvd., Los Angeles, CA 90015. www.as-is.la

-

The Call of the Wild

By the time my studio visit with Francesca Gabbiani is winding up, the conversation has turned to Griffith Park. We talk about our respective walks, and various neglected areas of the Park—the depleted bird sanctuary and abandoned spaces and cages near the Zoo—and the spirits that haunt those spaces. Gabbiani became obsessed with the dark history of the Park’s benefactor, Griffith J. Griffith. Less than a decade after the 3,000-acre bequest that became his namesake park, he nearly killed his wife, Christina, by shooting her in the eye, leaving her permanently disfigured—a crime for which he served two years in prison.

Something of Christina’s spirit may remain in the park; but our fascination speaks of a more extensive legacy of human and wild life marking the landscape. Coyotes can occasionally be heard howling in the early evening and their alarm signals a warning beyond their dark sanctuary.

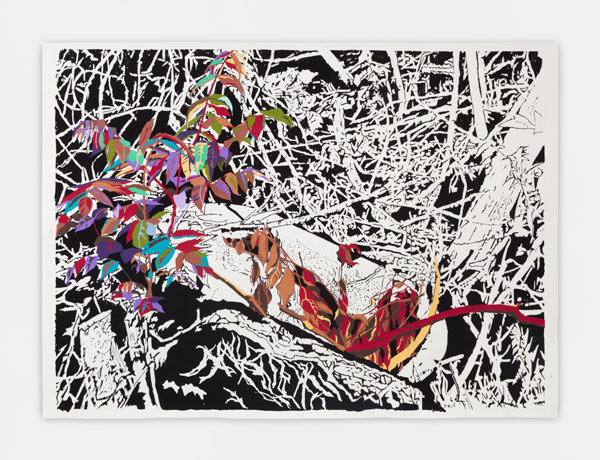

You sense the “call of the wild” in Gabbiani’s work, even through its intense artifice and deliberation. Beyond the elaborate mapping and breakdown of the image (whether physical landscape, domestic or interior space, or what we might just call the dark vortex of the imagination) preparatory to its rendering in the cut colored papers and various pigmented media (inks, gouache, watercolor, acrylics) she has made her signature, her process is a decoding and recoding, a continuous reconsideration of places, their constituent phenomena, and what we might call, in perceptual terms, their “aura.”

Situated on the flanks of Atwater Village, Gabbiani’s studio has the feel of a refuge on the gray day I visit her. We trade notes about some of the shows we’ve taken in the night before—and I’m not at all surprised to hear she admired the same John Divola “running figure” photographs I did at a downtown gallery. I mention the abandoned, vandalized shacks, sheds, boathouses and the like Divola brought to vivid life in the late 1970s that resonate with Gabbiani’s recently exhibited work. “He’s done that in photos and I have, too.” Gabbiani’s view takes a broader, exteriorized view in this work, but it is the continuity with her earlier work I pursue in our conversation.

Destruction of a Radical Space, 2015. Gabbiani has fixed her eye upon many film-worthy houses and domestic interiors since her arrival in Los Angeles in 1995. At one point in our conversation, she mentions one of the first she sighted driving around Los Angeles—an “Asian-looking house” that appeared in John Cassavetes’ 1976 film The Killing of a Chinese Bookie. As I follow her around the studio, the movie pedigree of other images from past works or works in progress is disclosed—between fires, a subject she returns to in her most recent work (“spectacles, I call them”)—an ironic segue from the surreal horror films and LA film noir that have been a constant inspiration in her work. “This is a real house on fire—well it’s actually a dollhouse from [Terrence Malick’s 1973 film] Badlands.”

The darkness goes back as far as the abandoned houses and spaces she once occupied as a squatter after leaving school in Geneva. “There were all these empty spaces. They were very dark; the staircases could break, but all those empty houses and spaces became a refuge.”

Dead Nature with Bathtub, 2017 The tenuous refuge or sanctuary is another through-line in her work—the disused or abandoned site that becomes a vehicle of transformation. “Why is it a refuge even though it’s scary?” She returns momentarily to Bachelard’s notion of the “attic or cellar” that might be regarded as a nest; and “why does it feel like home? I can stay there because I can change it maybe.”

“I kind of make it fantastical.” Gabbiani trails off here, but seems to confirm the connection between tenuous sanctuary and the elements of fantasy, even horror, that might be invited in right alongside. “I’m interested in the ephemerality of those spaces,” she says, “if there is an ephemerality to them.”

Installation view, Vague Terrains/Urban Fuckups, Gavlak Los Angeles, April 13–June 9, 2018 ), courtesy of the artist and Gavlak Los Angeles / Palm Beach. The fire in one sense or another has never been far off. Gabbiani has been no less moved by the “spectacle” of the recent wildfires and their destruction than the rest of the city, and she recently turned her attention to the aftermath of the burn—not so much the charred landscape that might be yet another black ground, but the smoke and miasma of debris clouding the atmosphere. “I’m trying to work on smoke. There were a few times I’d been on hikes when the mountains were on fire; and I’d be looking at mountains surrounded by smoke. So how do I do smoke?” Gabbiani shows me an array of fragments in sfumato variations—smoky indigos, blue-grays and inky blacks, mostly in watercolor and gouache. The atmospheric studies become a fresh groundwork for “the fluidity of the paint and the opacity of the paper” on a technical level, and perhaps an exploration of chaos—a systemic ephemerality on another level.

-

Ezrha Jean Black’s TOP PICKS OF 2018

I make no claim as to the comprehensiveness or objectivity of this selection. Nevertheless, to the extent that it reflects personal priorities, I believe most artists, if not the entire art community, both local and international, acknowledge the existential criticality of the moment. In one way or another, each of these exhibitions has engaged this moment as it intersects with a specific place or places—fractured foundations extending no further than consciousness and destined to vanish. As always, beauty is privileged, the sublime revered.

Marsden Hartley, Adelard the Drowned, Master of the “Phantom”, c. 1938–39, oil on board, 28 × 22 in., The Frederick R. Weisman Art Museum at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, bequest of Hudson D. Walker from the Ione and Hudson D. Walker Collection. Outliers and American Vanguard Art

LACMA

In an age of catastrophic displacements, LACMA’s (and the National Gallery’s) exhibition surveyed an intersectional expansion of consciousness between the culturally endorsed and what the conventional critical discourse can’t (or won’t) process.

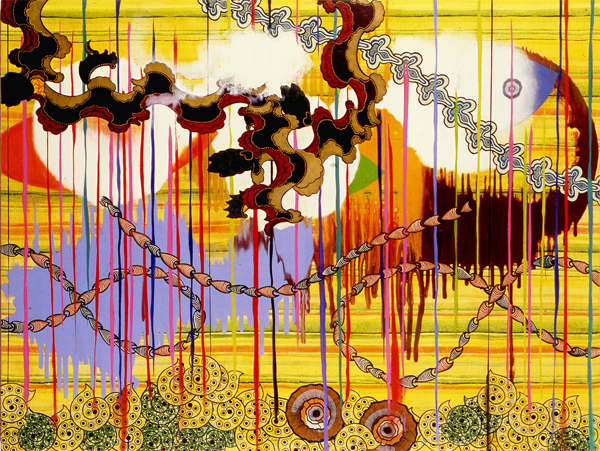

Merion Estes, Undercurrents (2003). Fabric collage, acrylic paint on printed fabric, 54 x 72 inches. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Matt Kazmer. Merion Estes: Unnatural Disasters

Craft & Folk Art Museum

This compact retrospective was an aurora borealis to throw light not merely on the Sixth Extinction, but the attenuated human consciousness that set it in motion—and Estes shows us beauty in the dying light.

Cauleen Smith, Remote Viewing (2009). Video still, 15:13 minutes. Courtesy of the artist, Corbett vs. Dempsey, Chicago, and Kate Werble Gallery, New York A grammar built with rocks (Carmen Argote, Julien Creuzet, DAAR, Sandra de la Loza, Regina José Galindo, Adam Khalil, Zack Khalil and Jackson Polys, Zara Kuredjian, Uriel Orlow, Gala Porras-Kim, Susan Silton, Cauleen Smith)

Human Resources

A geo-cultural archaeology of the human trace, the stain of consciousness and identity, the violence and social politics of survival—a break-through intersection of art and natural history.

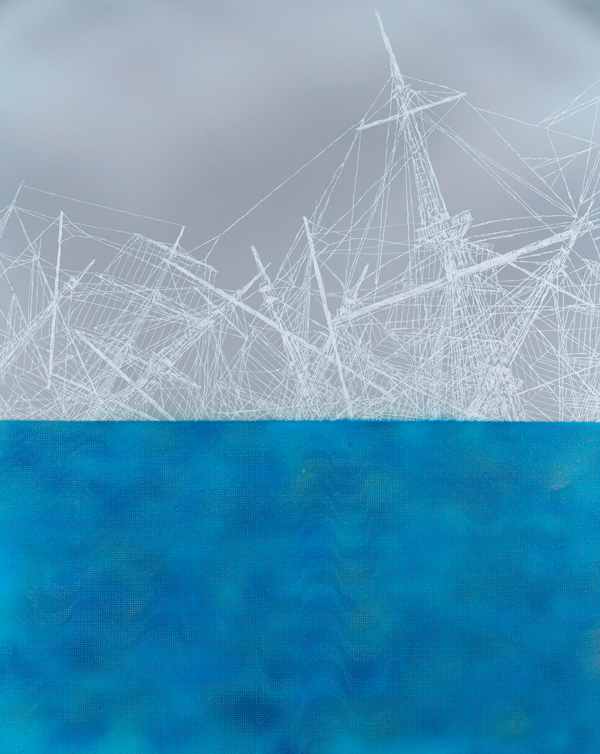

Christopher Russel, The Explorers #4 (2017). Pigment print scratched with a razor, aerosol paint, 44 x 35 inches. Unique. Courtesy of the artist and Von Lintel Gallery. Christopher Russell: Explorers

Von Lintel Gallery

Russell’s work deconstructs romance to stoke fires both sacred and profane—an acid IV-drip seeping into consciousness subliminally to set our synapses on fire.

10. Channa Horwitz, Canon Untitled (c. 1983). Casein on graph mylar. Framed Dimensions: 15 x 15 inches (38 x 38 cm). Courtesy the artist and Ghebaly Gallery, Los Angeles. Photo: Kell Yang Sammataro. Channa Horwitz: Structures

Ghebaly Gallery

Possibly the best exhibition of Horwitz’s groundbreaking work to date, the show put both the rigorous musicality and architectural scope of her work on display to sublime effect.

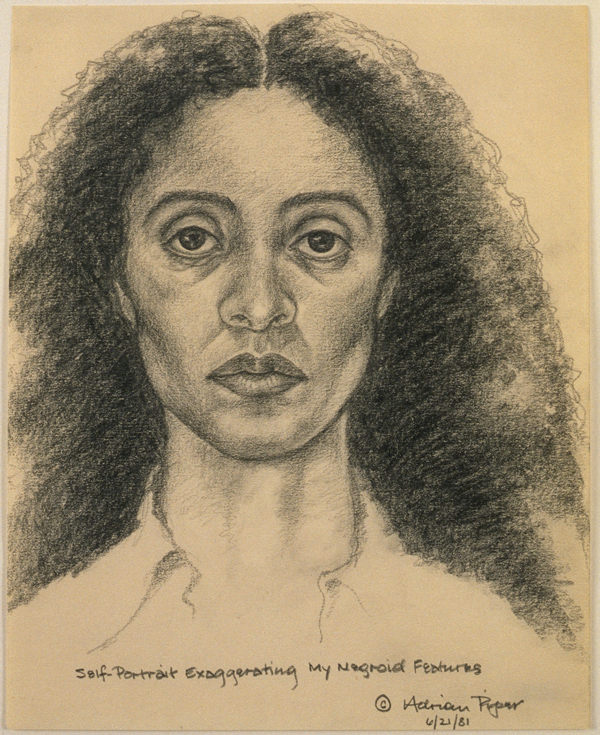

Adrian Piper, Self-Portrait Exaggerating My Negroid Features (1981). Pencil on paper. 10 × 8 inches. The Eileen Harris Norton Collection. © Adrian Piper Research Archive Foundation Berlin. Adrian Piper: Concepts and Intuitions, 1965–2016

Hammer Museum

Underappreciated in the U.S., Piper’s work comes as an austere yet exuberant wake-up call: “Everything will be taken away”—she’s not kidding around.

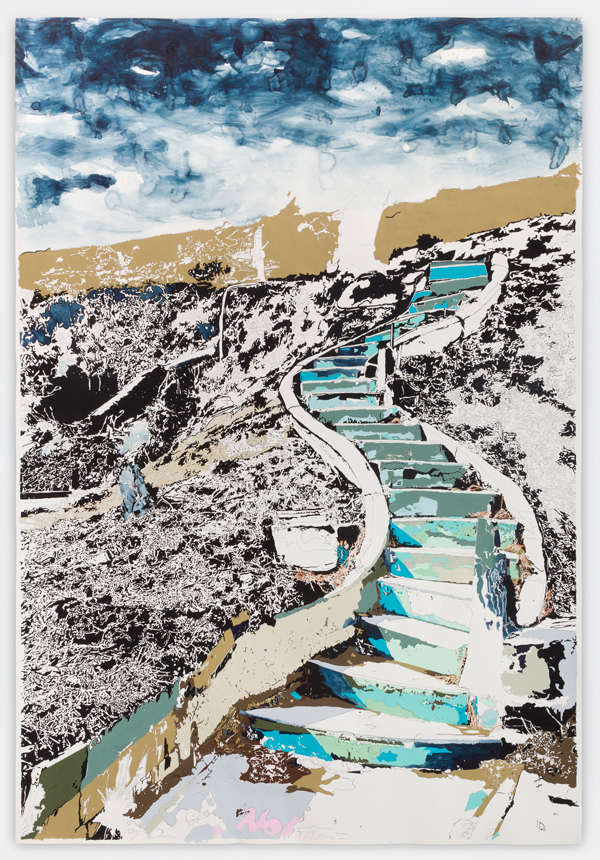

12. Francesca Gabbiani, The Unresolved Story (2016-2017). Ink, gouache and colored paper on paper, 105 x 72 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Gavlak Gallery. Francesca Gabbiani: Vague Terrains/Urban Fuckups

Gavlak Gallery

Gabbiani’s dark mirror visions have gradually given way to the quotidian nightmare, and she is fearless and alive to it, reclaiming beauty from the ruins.

13. Danial Nord, Cloud Nine (2018), installation view. Photo credit: Gene Ogami. Danial Nord: Cloud Nine

Torrance Art Museum

Nord’s installation effectively walked us through hell’s gates and into its ninth circle, i.e., the contemporary human condition, showing us how our hyper-connected, mediated society manages to function in nature, yet simultaneously against nature.

Jess: Secret Compartments

Kohn Gallery

A cross-section of the most formative periods of Jess’s work, this museum-scale exhibition gave full-throated voice to the disparate beauties from the enigmatic to Arcadian Jess prized from the crevices of his imagination and the world beyond.

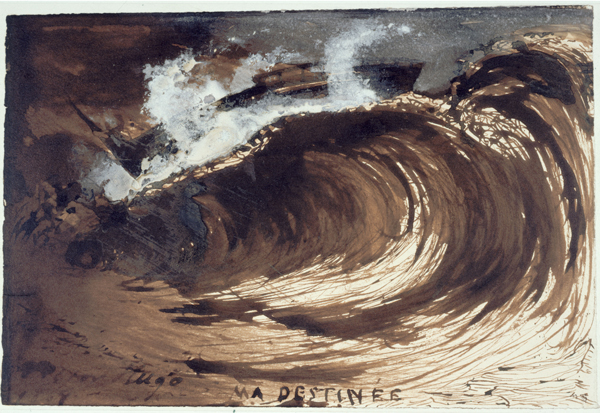

Victor Hugo, Ma destinée (My destiny), 1867. Brown ink and wash and white gouache on paper. 6 3/4 × 10 3/8 in. (17.2 × 26.4 cm). Maisons de Victor Hugo, Paris / Guernesey, MVHP.D.927 © Maisons de Victor Hugo, Paris / Guernesey / Roger-Viollet. Stones to Stains: The Drawings of Victor Hugo

Hammer Museum

Hugo, acknowledged literary master, is revealed in this exhibition as visual artist of jaw-dropping visionary power, anticipating 20th century developments as diverse as abstract expressionism, art brut, and Raymond Pettibon.Honorable Mentions

Nicole Eisenman: Dark Light, Susanne Vielmetter Los Angeles Projects

Roland Reiss: Unrepentant Flowers and New Miniature Tableaux, Diane Rosenstein Gallery

Julie Curtiss: Altered States, Various Small Fires

Bamboo, Craft & Folk Art Museum

William Lamson: Badwater, Make Room

-

After The Price of Everything

As we raked through ashes in California, reminded that we had already entered an anthro-obscene geological epoch, the most “important” of the Fall 2018 art auctions were already taking place, with records dropping every step of the way—Hopper, Hockney, Jack Whitten, Jacob Lawrence (with unusual drama), even our own Henry Taylor. But as any stand-up comedian or Sotheby’s own Amy Cappellazzo will tell you—it’s all about timing. Which is why HBO had the good sense to drop Nathaniel Kahn’s The Price of Everything into theaters around the 45th anniversary of the 1973 Scull collection auction, and across its cable platform just before the first major auctions.

The title is a bit of a feint, a distraction from the real action which plays out off-camera (and arguably outside the art world altogether), which is both its attraction and (to a minor extent) disappointment. What saves the film is an awareness of its limitations, a rhythm and pacing reminiscent of documentaries like R.J. Cutler’s The September Issue (2009), which tracked the dynamic yet conflict-riddled editorial process leading up to the publication of the September 2007 edition of Vogue, and some, well, priceless moments that played out the tragicomedy of values under the screened action like a string continuo under a brass choir. It doesn’t exactly end with a bang, but then—see auction results above.

4. The collector Stefan Edlis, as seen in “The Price of Everything.” Courtesy of HBO Can it really be much of a surprise? The hammer falls, the sales close, and everyone moves on to the next shows, acquisitions, auctions, etc. But as we knew in 2018, the most rational expectation is for the unexpected if not actually catastrophic. The fire THIS time, as James Baldwin might have put it. To his credit, Kahn and most of the major players featured in the film (with the possible exceptions of Jerry Saltz and Jeff Koons) have some idea of where it’s all heading, but continue to perform their roles, not always aware (as in the Wilde play that inspired the title) of the extent to which they embody the dubious values and verities of this world in varying degrees of conflict and alignment.

Paul Schimmel and Gavin Brown actually give voice to this underlying reality, but Kahn is content to leave what Schimmel correctly identifies as a “bubble” floating. Brown in turn sees the “edge” the art world is careening towards (“I can smell the smoke!”), but seems helpless to do anything but drift along with the tide of the commercial cycle. He’s a part of this world, too—with artists of his own to promote and a business to run.

What the film skirts, and is only partially in play in most of the major fall and spring auctions, but can be glimpsed in the film’s interstices and certainly felt throughout, is the real passion animating this commerce: the thrill of the chase. The excess of contemporary commercial culture is sufficiently developed here. What we don’t see is the passion, even obsession, behind the quest to find and possess these objects. But this passion animates collecting at every level of the art market, and not just the upper reaches of the auction market that really take in no more than a few hundred collectors.

9. The collector Stefan Edlis, as seen in “The Price of Everything.” Courtesy of HBO This is something that can’t always be quantified or laid out on a spreadsheet (we catch collector and philanthropist Stefan Edlis doing just that at one point in the film)—which is presumably why Kahn turns to former ABC producer and sometime social satirist (The Manny) Holly Peterson, who also happens to be something of a collector. Peterson can see where this crosses over from fashion or mere social status-seeking to serious neurosis. But we don’t need a chart-busting balloon-dog to see that at the upper reaches of this market, this clearly crosses over into something akin to social pathology. Have a look at the sales results from the November contemporary auctions, and you can see that for quite a bit less than $60 to $90 million, you could take home an entire collection of market-approved blue-chip (and some actual first-rate) art.

There’s a certain retail glamour to big art-auction evenings—and they usually are evenings, traditionally in May and November, usually in New York and London. But the glamour lasts about a minute. These are fairly businesslike proceedings and the auctioneers move through the lots briskly. There are big auction dates in other cities, too; but in the art world, these are the most visible, high-profile sales where the most highly valued lots tend to be aggregated, frequently around a major estates liquidation or collector’s de-accessioning, but usually including more than one major slice of what we might call legacy holdings. This is where you find a kernel of truth in Simon de Pury’s simultaneously grand and crass summation, “It’s very important for good art to be expensive.”

2. The artist Njideka Akunyili, as seen in “The Price of Everything.” Courtesy of HBO The distinction we might draw is durational: before mid-20th century, the works of art that changed hands at these stratospheric levels were not only masterpieces but held over a span of one or more generations. The overheated and inflated postwar and contemporary art-auction market has completely distorted otherwise rational economics. Now the lot considered for sale may have been held only a few years. It may or may not be about a collection or collecting—or even flipping. The seller may simply be cashing out, entirely disengaging from the market or re-entering it at another level. What we increasingly see now is something more on the order of a NASDAQ for, let’s say, recent public offerings, as opposed to holdings—with fashion and sheer speculation taking the place of substantive criteria.

One of the treasures of the Kahn documentary is the archival footage of the October 1973 auction of the Scull collection of late 1950s abstraction, Pop and Minimalist art. It’s a vivid slice of Manhattan social as well as art history—the “Scene” moved uptown. But the 1973 Scull auction did not by itself trigger the escalating speculation in the contemporary art market that followed; and as usual, there’s a back story: the Sculls’ marriage was on the rocks. Within a year, Ethel filed for divorce (a story all by itself).

3. Sotheby’s Amy Cappellazzo, as seen in “The Price of Everything.” Courtesy of HBO The thrill of the chase is still there—just ask Sotheby’s Executive Vice President and Contemporary Art Chairman, Amy Cappellazzo, whose brand is on abundant (and entertaining) display in the Kahn documentary. But in the late-capitalist auction marketplace, it’s given way to something else. Call it the frenzy to disown, the fear of missing the cultural ‘sell-by’ date. It’s not about the prize, the masterpiece, the collection. It’s about currency—and you can always find a trade war if you want to look for one in that marketplace.

8. The artist Larry Poons, as seen in “The Price of Everything.” Courtesy of HBO “How do you stay sane when your paintings go for a million dollars at auction?” Marilyn Minter asks, half-surprised even to be alive to see it. Kahn’s documentary paints Larry Poons as the artist in voluntary self-exile from the commercial circus of the New York art world, pursuing the elusive grail of his vision. But Minter’s career is far more instructive with respect to the caprices of both commerce and culture. Although Minter’s work has been striking from her earliest, quasi-experimental work, only in 1995 did it begin to reach the platform it long deserved. Poons, by contrast, was immediately successful, debuting at Green Gallery and eventually moving to Castelli; and his comeback has been well underway in this century. As Kahn’s documentary closes, Poons walks uptown from a festive opening at his Manhattan gallery, not incidentally passing a shop window displaying licensed merchandise by Jeff Koons. It’s the slow exhale on the film—and a chapter in the culture of late capitalism spinning out of control in plain view. Kahn’s film puts an ironic lens on what might have been a satyricon of serial excess. But you can’t argue with supply and demand. Or can you? Barbara Rose seems to here. Even Phillips’ Chairman Edward Dolman sounds a cautionary note (en route to a $1 billion year for the house): “[T]here’s a temptation for artists to over-produce.” Although Kahn can’t show us all aspects of even the auction market, between Poons, Minter and several others, he gives us a fair circumnavigation of its northern latitudes from the artist’s viewpoint.

There isn’t a lot Amy Cappellazzo doesn’t know about selling art. Her attitude and approach were well documented in Sarah Thornton’s 2008 trans-sectioning in Seven Days In the Art World. We pick up a few more angles on it as she runs through “comps” with an assistant putting together an auction catalog. But it’s not as if Cappellazzo (or Kahn himself) doesn’t comprehend the larger cultural context and the imponderables concealed within the market calculus. It’s only becoming more complicated as we begin to see works that inhabit the gray zone between object or document and performance entering the market: performance works sold to institutions and in the secondary market, works produced by artificial intelligence.

But the chase only takes you so far. It’s in the enduring proximity afforded by possession where the “grail” mythos (or Pandora’s box) unlocks its secrets. Cappellazzo is not exaggerating when she says “[a] painting like that could change your life—if you let it.” We feel the double freight of that line. It’s the curse of the Hope Diamond magnified into full-scale Shakespearean tragedy. It’s in these moments where we glimpse the more incalculable values prized from the interstices of these transactions. So why not “keep it floating”? It’s the only place we want to live.

-

Sarah Awad

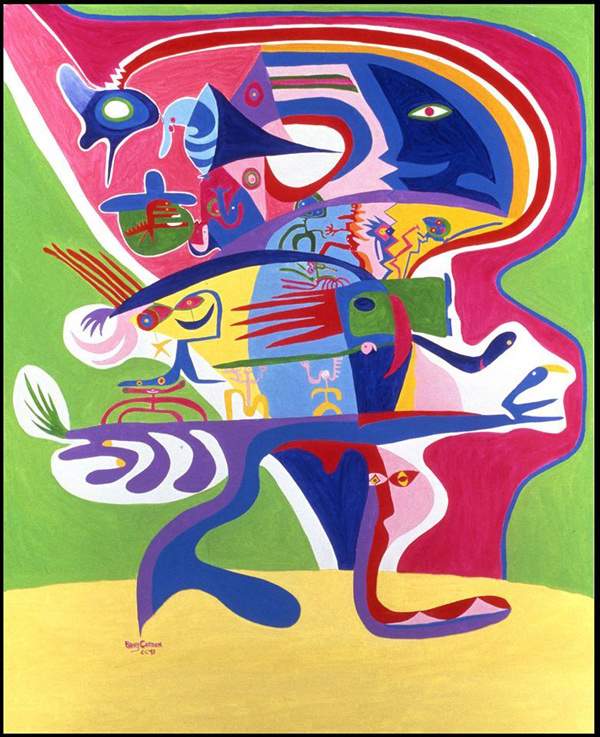

The title of Sarah Awad’s recent show seems intended to encapsulate its scope, which is as expansive as the painting from which it’s borrowed. However appropriate it might be for that particular painting, applying it to the exhibition as a whole, though, seems arbitrary and limiting. Even that work itself, Double Field (all works 2018), suggests aspects through which our view might be further expanded and refracted.

Reflection may be implied, as the gallery’s notes suggested, but also simply doubling, shadowing, or even foreshadowing. (Consider the figure in the upper right and its “ghost” limned a few feet opposite.) Although the work’s willful abstraction would seem to preclude a narrative address, Awad does not shy away from the psychological or the temporal dimensions of the work. The fractured composition is echoed by its discrete durational zones. It’s less about reflection than multiple-exposure—a temporal as well as spatial superimposition.

Everything All At Once might serve as a kind of index to Awad’s means of abstraction—from its primary-dominant palette which nevertheless didn’t shy from the monochromatic to the melding of figurative elements into an alternately dense or thinly abstracted mass. In other words, Awad was willing to subordinate layered, figurative, incidental, ghosted or merged human body parts to the composition as a whole. The sharply articulated or delineated coexisted side-by-side with the densely abstracted or even obliterated. Here the sense of doubling or reflection seemed to carry a clear time signature: the “sustained” figure (violet-brown face, green nose), interrupted (split-face) or followed by two further abstracted or even ‘faded’ figurative elements (blue; then pale yet distinct—all submerged into the mass); the surface incident supported by dense undercurrents of subordinated and entirely abstracted figuration.

Sarah Awad, Double Field (2018), courtesy Night Gallery. Sense and sensuality are abundantly referenced, however faded or submerged. The central figure in Liz Caught in the Act might be reaching, grasping, or more specifically grooming or gesturing. These are bodies that relate to themselves and others, but also to past incidents or incarnations. The figures in Night Swim are lost in dense sapphire and indigo that is in the lower emptied-out quadrant of the canvas. A figure may push forward from its abstracted ground to boldly assert a geometric contour—e.g., the sharply delineated crescent of cantaloupe cleavage in Derriére. Within the compass of her aggressive abstraction, Awad is not hesitant to invoke the classical figure in these paintings, which underscores their deep reference (if not reverence) to the past.

This is the central tension of the work—between reflection and transparency, social and solitary relations; with every element working in concert, yet as if in a kind of absence of unitary consciousness. However distinct her signature, Awad seems prepared to set her own authorship to one side. Beyond classicism, they invoke a view of the cosmos, from which the fulcrum at the center of these mechanisms may be allowed to vanish.

-

Hammer Museum’s Annual Gala in the Garden

Is it wrong to feel like dancing on a school night? The gent sitting next to me didn’t even get to cross that bridge—he had to exit early for a drive out to Malibu on a school-related mission. But whatever you thought of Leon Bridges’ laid-back-going-on-languid set, he might as well have been singing smart speaker installation instructions after Bryan Stevenson’s riveting introduction and tribute to Glenn Ligon, one of this year’s honorees at the Hammer Museum’s annual Gala in the Garden. In these “If It Feels Good …”— than it probably isn’t—times, this smartest of public speakers struck a chord (or chords—it was really a kind of anthem)—that connected both philosophically and viscerally with his receptive audience. Even Ligon seemed at least as moved by Stevenson’s eloquence as the honor itself.

Glenn Ligon (L) and Bryan Stevenson, Photo by Stefanie Keenan/Getty Images Ligon rose to the occasion, paying tribute both to his co-honorees, the Hammer, and the larger institutional context, acknowledging the preceding year’s honorees, Hilton Als and Ava DuVernay, Stevenson himself, and Stevenson’s vital work as the director of the Equal Justice Initiative. He immediately recalled Stevenson’s inscription of his copy of Just Mercy, Stevenson’s best-selling memoir of his work appealing wrongful convictions and capital cases at a book-signing event in New York—“With hope.”

Michael Chabon, Margaret Atwood, and Armie Hammer, Photo by Emma McIntyre/Getty Images If I could put my finger on what we were collectively feeling after the speeches had wrapped and we were waiting for dessert, that would come closest. A little hope is a dangerous thing—just ask Margaret Atwood—and backed with Champagne and a few delicious tequila cocktails it can wreak havoc. Atwood (and Michael Chabon—whose introduction seemed laborious beside Stevenson’s ex tempore pyrotechnics) seemed to be banking the fires Stevenson and Ligon had stoked to a roar, dangling her own slender thread of hope against the backdrop of all we were celebrating that evening. (But I noticed she didn’t really touch on the environmental concerns addressed in some of her novels.)

Armie Hammer, Tom Ford, and Elizabeth Chambers, Photo by Emma McIntyre/Getty Images I would have enjoyed meeting Will Ferrell, Armie Hammer and Tom Ford (to say nothing of Solange Ferguson and Darren Star, co-chairs of the event with Elizabeth Segerstrom), but the Hollywood glitterati faded before Stevenson’s visionary glow and I bee-lined it for his front-and-center table. Always in the right place at the right time, Michael Govan was positioned between Stevenson and LACMA besties Lynda and Stewart Resnick. I’m hoping they matched Stevenson ‘capital’ for ‘capital’ and wrote him a WONDERFUL check before the evening was over.

Will Ferrell, Photo by Emma McIntyre/Getty Images I didn’t meet Darren Star (which was a shame—I have a show to pitch and was I ever in the mood); but master showrunner (and benefactor) Marcy Carsey was right up front in a gorgeous silver blazer and I had to wonder how Stevenson’s, Ligon’s and Atwood’s remarks resonated with her own television legacy. Actress-producer-director and longtime Hammer supporter Susan Bay Nimoy was close by, elegant in a black wrap and gown Margiela. It was an evening for power dressing and power building. Amongst the couture-clad were political (mostly Democratic I’m happy to report) power-players, and actual architects and builders; and we were reminded that the Hammer’s expansion into the adjoining Oxy building was still under way. Frank Gehry, Kulapat Yantrasast and Edwin Chan were all there, though I didn’t see master-of-the-expansion Michael Maltzan.

John Waters and Greg Gorman, Photo by Donato Sardella/Getty Images I could only wave to John Waters as I made my way back to my table. He blew a kiss I knew was intended for my editor. As I sidled past impossibly elegant masters of this domain like Stephanie Barron and Andrea Fiuczynski, all of us dazzled by Stevenson, I felt a twinge of nostalgia chatting with Jeff Poe, who held court at a table of B&P friends and artists (including Dave Muller), and earlier with Margo Leavin and one of her former artists, Roy Dowell, who was there with Lari Pittman. Naturally there was a heavy Regen contingent, including Theaster Gates and Cathy Opie.

Michael Kohn, photo by Ezrha Jean Black I was equally in the thick of it at my own table where I was seated between Simone Manwarring of Sprüth Magers and Michael Kohn, and across from the artist who had invited me to join this power set, Diane Silver. Contemporary art, Waters would have reminded me, might never welcome me—but, with the Hammer’s Public Programs Director, Claudia Bestor, so critical to the Hammer’s engagement with a broad range of public issues, seated only a table away, I felt reassured that the Hammer invites everyone into its generous and vital forum. Annie Philbin had already announced the event had taken in $2.6 million, and I took pleasure thinking about how creatively Philbin, Bestor and the rest of the Hammer team would be spending it.

Annie Philbin and Michael Govan, Photo by Stefanie Keenan/Getty Images “I think Glenn is a free man,” Stevenson said of Ligon—and we were all aware of being included in that moment, celebrating both freedom of consciousness and consciousness of freedom. There was an impressive Assouline-published coffee table book waiting for the exiting party guests; but I wish they had just handed us cards telling us the cost of the swag was being given right back to the Hammer—or just as nicely, Stevenson’s Equal Justice Initiative. The moment for dancing may have passed, but the moment for giving is ever present—and urgent. For gifts to the EJI, go to https://donatenow.networkforgood.org/eji. For the Hammer, go here: https://hammer.ucla.edu/support/ or call their Development Department. Above all, just go.

-

Tieken Gallery: : Simone Gad, Barry Gordon, Gus Harper

There is something delicious about the commingling of delight and horror, or really any opposition of sensations pushed to their extremes: confectionary sweetness with an aftertaste on the wrong side of savory—the foreshadowing of decay; the sweetness of rain-drenched foliage followed by the mineral-laden scent of ozone rising from the dampened earth; the little girl in the red rain slicker and wellies who turns out to be an axe-wielding dwarf.

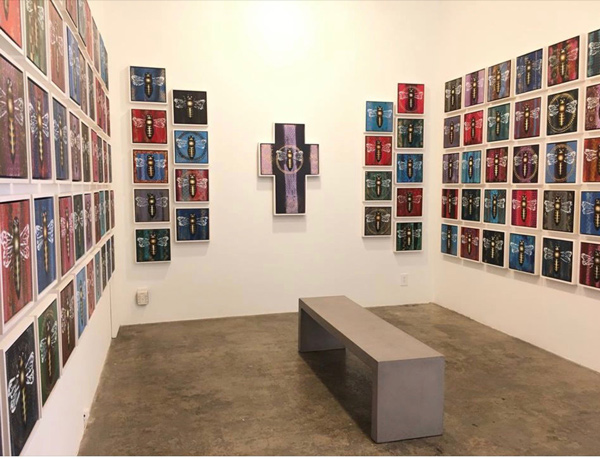

Barry Gordon, Societal View: Stable Table and Other Life Patterns. Oil on canvas, 50 x 40 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Tieken Gallery. You can almost taste this odd chemistry in the group show up at Tieken Gallery in Chinatown—something of a lost, corrupted dream of childhood that’s somehow better, more richly appreciated the second go-round. Or even hear it—in the banshee scream of color issuing from the almost abstract idylls of Barry Gordon, who might be the artistic love child of Joan Miró and Jay Ward; or the menacing hum of a swarm of bees: there’s a room (or hive?) of more than a hundred by Gus Harper, who has made something of a specialty of his obsession.

Gus Harper, Good Luck Bees, installation view. Courtesy of the artist and Tieken Gallery. A room like that might drive you mad; which is why we happily return to the angel fish serenely swimming alongside a cetaceous lamprey spouting a plume of vasculature morphing into saguaro cactus, or birds with whiplash plumage contending with ferocious flying fish in Gordon’s Ernst-inflected fractured fairy tales.

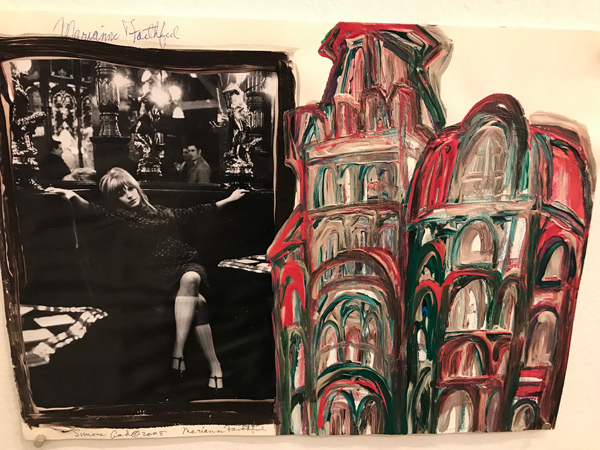

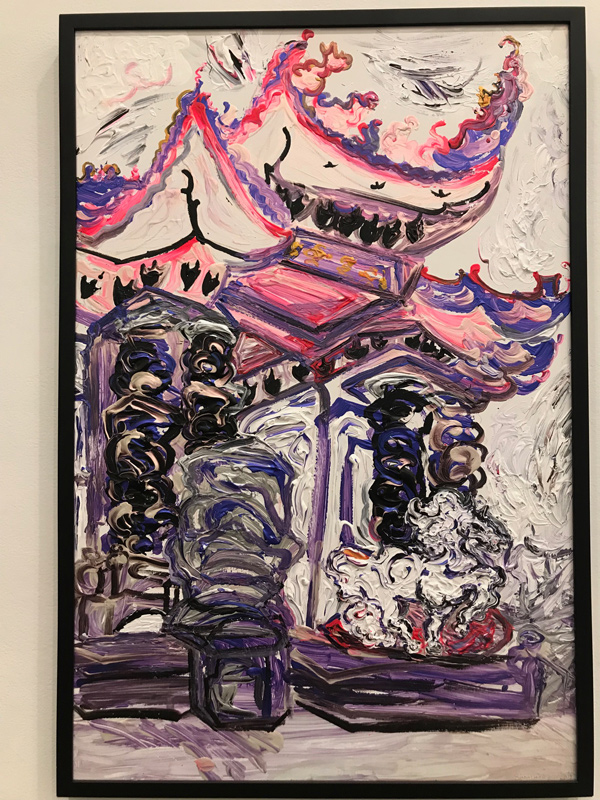

Simone Gad, Auto-Portrait à Chinatown (2018). Photo by Ezrha Jean Black. Then we come to the temples, pagodas, bars and shop windows of Simone Gad. We can call this Chinatown, but it’s really a magical city where the forbidden is both mourned and celebrated. The upturned, artichoke-leaf roofs effervesce and explode in red, from carnation and carnelian pink to rich scarlets, crimsons and Chinese reds. Darkened recesses in slashes of blue and black are framed by yellows and impastoed whites as thick as frosting. Bright yellow shop windows become jewel cases melting away their treasures.

Simone Gad, Buddhist Temple on Alpine Street (side view), 2018. Photo by Ezrha Jean Black. Directly alongside is a selection of Gad’s no less thickly impastoed works on paper with magazine collage from a decade ago, dark meditations on the lingering gaze of fame. Gad carves out a safe and sacred space for black framed magazine-print beauties like Ursula Andress, Marianne Faithfull and Pam Grier in Victorian-Italianate arcades and cupolas—wood-butchered doll-opera houses in slashes of red, blue, verdigris and turquoise to hold their faces and voices like the luminous vessels they are. There’s such incandescent joy and sadness in this work. Gad has a finger on the fetish she plays like a Mozart cadenza.

Simone Gad, Barry Gordon, and Gus Harper, September 8 – October 13, 2018, at Tieken Gallery LA, 961 Chung King Road, Chinatown, Los Angeles, CA 90012. fredtieken.com

The artists will all be present at Tieken Gallery for conversation and audience questions this coming Saturday, September 29th at 3:00 p.m.

-

Harry Dodge

When does an exhibition title effectively amount to a viewer advisory? I’m not sure Harry Dodge would consider the title of his current show at JOAN gallery, “Works of Love,” an instance of this. It’s not in any sense a caution, and the titles of the individual works freely contradict or complicate this intention. But both the titles and more importantly the works themselves reflect a posture that veers between deflection or distraction and abject immersion.

The placement of Accidental Megastructure (2018) closest to the entrance might serve as a groundwork for the terms and conditions of Dodge’s “love” for exchange or expression here. “Megastructure” would be the human form itself—here represented as a grotesque over-the-head carnival mask (originally an Incredible Hulk mask). There’s no indication Dodge has seriously altered it, although the “blood” seeping from the eyes looks like an addition and the hair seems expressionistically enhanced. Below this mask at the base, is what might be a kind of reversible mask—the sort of face seen in a silvery cloud, one that might be read upside down or from either side, its mouth really a kind of beak defined by proboscis and jaw, of a piece with the sorts of blob-like heads that seem to routinely crop up in Dodge’s drawings and installations.

Harry Dodge, Black Transparency (The Cloud Polis draws revenue from the cognitive capital of its Users) (2017), courtesy of the artist, photo by Paul Salveson. From the human form and its most evanescent sublimation, Dodge moves towards a domain clearly inspired by AI and robotics. Megastructure (or monstrosity) gives way to instrumentality—being in the world as catalyst or cataclysm. Most of the sculptures have similar armatures constructed of aluminum tubes and panels of wood or Plexiglas joined by aluminum speed-rail joints; but whether human and “mega,” exigent or futuristic, feral or simply “strange,” Dodge’s mega-machines are dark handmaidens with several of the sculptures cast in bronze. In Feral Sympathy (Works of Love #4) (2017), a jumper cable is clamped to Dodge’s pump-jack half-mask (with another clamp at its “tail”). Invisible Helpers (Works of Love #2) (2017) are not just visible, but emphatic, with their rake-like digits (or teeth) and framed viewfinder “eye.” In the worldview Dodge gives us here, it may be that the viewers themselves are the future “invisible.”

We understand from Dodge’s written statement that his notion of “being-with” (as a “practice of love”) does not exclude the non-human. The “Works” however raise two questions: does it also (following the terms of the theoretical writing of Édouard Glissant that informs Dodge’s thinking) encompass the complex, organic “non-single” being we know as the human; and can we really call an artificial intelligence that, however autonomous, remains the product of human manufacture, “non-human?”

Dodge doesn’t call all of the works in this exhibition “works of love.” From “Work of Love #5” titled, The Monstrous Interval (2018), also in cast bronze but with a distorting mirror framed opposite a pair of rotor-like attachments—as if to remind us how mutable we are—we move on to a black urethane-soaked sock that looks more like an oil-slicked crustacean than Dodge’s title for it—Pure Shit (2017). But this is a mere trial balloon by comparison with Dodge’s Pure Shit Hotdog Cake (2017), whose armature is elaborated by multiple receding trays, dripping in neon-colored magenta, neon-yellow, green and orange. Black, white, gray and silver dripping top to bottom are effectively the binary through-line. The speed-rail joints brandish their painted Plexiglas panels like shields, while an orthogonal transversal projects a decontextualized photograph of itself on one side, effectively both representation and virtual extension. The hot “sausage” atop this wedding cake is almost beside the point. The elaborate structure effectively wags the dog, reduced here to vehicle/receptacle for what might be called Van Gogh yellow condiments.

In a similarly elaborate work, explicit in its allegorical intent, Black Transparency (The Cloud Polis draws revenue from the cognitive capital of its Users) (2017), extensions threaten to fly off a vertebral stepped base, while yellow polyethylene buckets cascade a sheet of tar-black resin. Again, this seems less about an affective response to “being-with” our AI-endowed technology, than its material consequences.

Dodge’s struggle to evolve “being-with” is not far removed from the more fundamental problem of consciousness that is simply being in the world—the human consciousness of having reduced its biosphere to instrumentality and all but destroyed it. Love is both too inclusive and exclusive to serve as an apology; and it doesn’t need to be. Dodge’s “Works” here point to a larger leap—from the visible to the invisible, and the inevitable existential anxiety of that erasure.

-

Eileen Cowin

Eileen Cowin’s work has been loosely categorized as mise-en-scène photography. But overall it is far more self-reflexive, deeply deconstructed and concerned with the relations of language to the apprehension and (re-)construction of reality.

More recent work has introduced still richer layers of ambiguity: alternately stark and lush, the elements of suspense more pronounced, however contradictory, the mise-en-scène more sophisticated and brilliantly chromatic—though in “Do Nothing Until You Hear From Me,” her new work at GCC, the affective tone is, above all, gray.

Knock begins with an abrupt dislocation. An establishing shot of a pleasant urban overlook fades to black-and-white; a quick cut to an abandoned shed is flanked by a tracking shot past fenced enclosures and a tangle of woods. The narration instructs, “Imagine any big city… And imagine all human beings swept off the face of the earth.” In a dimly lit domestic interior, a figure: “except for one man.” A dream space made realistic by maudlin detail—pants undone, spectacles that inexplicably disappear, a terrier, the man apparently staring at a screen—and suddenly there is “a knock at the door.” Time stops or slows: a cup shattering in a kitchen sink, a bowl abandoned.

Eileen Cowin, Joke (2018), courtesy Glendale Community College. There is no knock, actual or symbolic, in Summons; a woman’s head emerges from a void, flanked by expanses of ultramarine bed-linen. The voice is internal, the subject’s own (and, as in Knock, unheard by the viewer: words and actions are given in subtitles). Here, too, another bisection—this time returning us to that gravel road and the fenced parkland, now identified as an abandoned zoo plucked from memory. Cowin frustrates our dream interpretation with micro-reversals. The subject declares herself an adept liar, until “stripped of all secrets.” The segment closes on the abandoned blue pillow—an emptied dream space.

Finally, in “This Is How It Was This Is What Happened,” the view is of the (male) subject’s hermetic apartment. He gazes furtively at a building next door, traumatized by a break-up. Again, details make their contradictory assertions: three pristine white shirts in a closet (he’s wearing one of them); the fire escape on the building next door; a television screen glowing glacial blue with a suggestion of alpine adventure.

Cowin intercuts this narrative with a “hate hour” clip from the 1984 Michael Radford-directed film of Orwell’s 1984—a kind of visual scream from a hypothetical Ministry of Truth. The subject sweats, and we’re told, “For the first time, he perceived that if you wanted to keep a secret, you must also hide it from yourself.”

All of this might be viewed as dream imagery, but the underlying texts (not merely Orwell, but P. D. James, Anthony Marra and Herta Müller) suggest subtle overlaps, specifically with respect to the traps humans set for themselves between their apprehension of reality and their ”correction.” Truth, it turns out, is a subtle business—more often gray than black-and-white. The inspired title, borrowed from the Duke Ellington standard, underscores the fraught, multiple ambiguities at play. By all means pay “attention to what’s said.” Cowin also urges us to pay attention to the way it’s said.

-

After Henry – or Thanks Be to Mark

As Karen Finley wisely counseled me some years ago, an excess of gratitude can strike you dumb (or simply annoyed speechless), which is never a good place to be, especially if you’re on a podium and expected to render judgment, offer smart advice or commentary, or simply deliver a few thoughtful remarks to a throng assembled in your honor and from whom your hosts will momentarily be asking for a few million dollars.

Mark Bradford and Henry Taylor

Elsa Longhauser and Henry Taylor There were a few moments like this at ICA’s otherwise delightful benefit brunch honoring Henry Taylor Saturday afternoon at ICA-LA’s unusually – ‘just-your-friendly-local-contemporary-art-institution-down-the-block’ – neighborhood accommodating digs in that windswept stretch of the arts district on Seventh Street between Alameda and Mateo. It was like a Sunday morning church service for the self-enlightened and forever fallen, a prayer breakfast for those of us who pray for something that’s either going to save the coral or introduce us to some ‘whole new motherfucker,’ as Henry might put it.

Joy Simmons, Patrick Martinez, Arthur Lewis, Henry Taylor, Hal Nguyen, Andy Rober. You’d think that was me, the way Henry greeted me, walking into the (what do we call that open-air space that feels like a bodega with nothing for sale?). Except that I believe Henry’s effusive greeting was actually for the motherfucker (a term of endearment chez Henri) directly behind me – his gallerist, Jeff Poe, standing just a few feet behind him and taking in the entire scene.

Brunch guests It was impossible to move more than a few feet without running into someone we knew – curators (Glenn Phillips, Ed Schad, Jill Monitz), collectors (Deborah Irmas, Beth Rudin DeWoody), dealers (Rosamund Felsen, François Ghebaly, Honor Fraser, Shulamet Nazarian, Tim Blum), journalists (Jori Finkel, Hunter Drohojowska-Philp) genius artists (Elliott Hundley, Brenna Youngblood, Todd Gray, Meg Cranston, Patrick Martinez). I only caught a glimpse of Charles Gaines, but his spirit seemed to hover over the ‘congregation.’ Running across Sydney D. Holland’s name amongst the supporters, I combed the crowd looking for her – it’s a long way from the heights of Mulholland Drive; but hey – if David Hockney can do it…. (no he wasn’t there). But Elsa Longhauser, ICA’s executive director, and board members Laura Donnelley (the chair) and Vera R. Campbell were – and you could tell they meant business.