I learned yesterday—along with most of the Los Angeles art world –that John Baldessari had died. (He had actually died Thursday, but the word filtered out only this week-end.) Long before I knew him or what he represented (not only in Los Angeles, but the world), and long before I wrote about fine arts in Los Angeles, I would see him frequently at art gallery openings. (I always had many artist friends; and in Los Angeles it was easy to fall into the habit of keeping an eye open for developments on that front.) There were odd jags when I would see him at several in a row, often in the same evening.

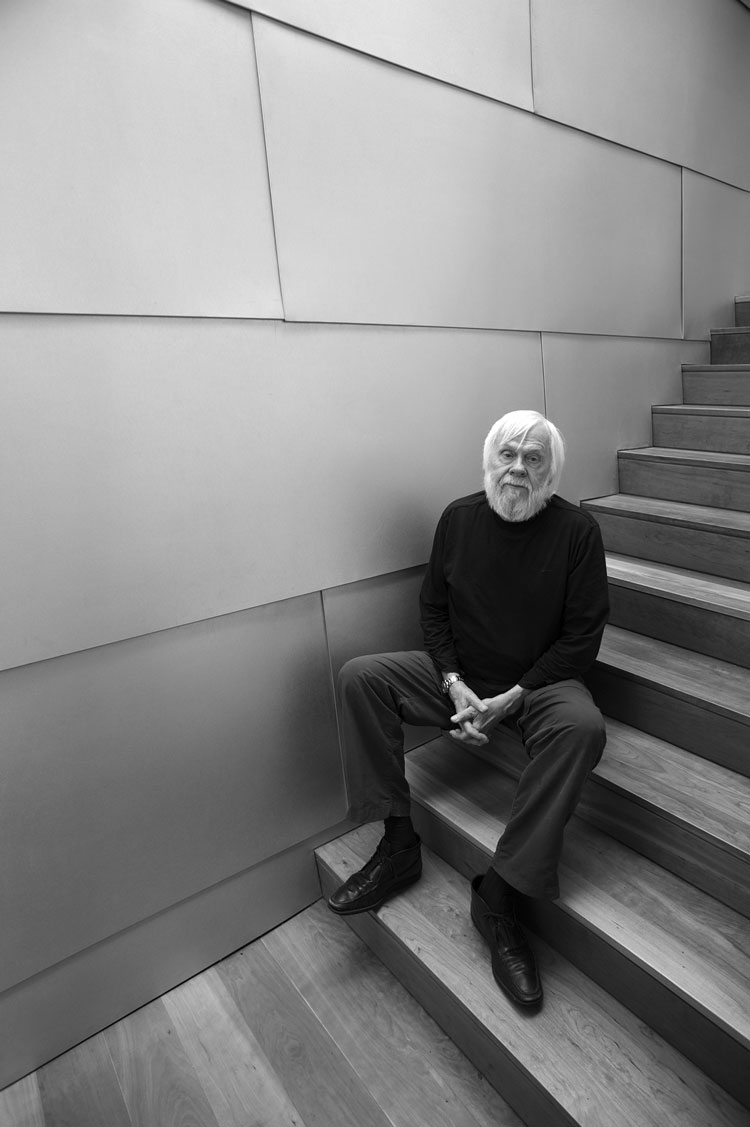

You couldn’t miss him. He was almost always the tallest man in the room and, even in his minimalist, pared down artist/teacher’s style of dress (usually a simple T-shirt or sweater and jeans), the most distinctive—with his thatch of white hair fringing his forehead and short white beard; and everyone seemed to know him. In other words, even before I knew him as the godfather of L.A. conceptualism, he was clearly the godfather of at least half the L.A. art world. He was by that time already quite famous – though it seemed as much by association with other artists as by his own work, some of which was already the stuff of legend. Even then, the scope of his influence hadn’t quite hit me.

The ‘legend’ finally saw ‘print’ in his hometown not long thereafter with his 1990 mid-career retrospective at MOCA; and it was probably only then that I began to ‘connect the dots.’ It was certainly the first time I began to fully contextualize his place in the larger art world (though even then I did not grasp the global reach of his influence). This was a way different kind of ‘cool’: cerebral but grounded; distilled more than abstracted; and informed by the entirety of actual and variously filtered or mediated experience. It seemed immaterial to me at the time that he had abandoned painting, or what might be considered traditional art media and the notion of hand facture.

John Baldessari, photo by Tyler Hubby.

But this abandonment was more than a mere gesture, in a post-Duchamp, post-Warhol sense. In retrospect it seems of a piece with his work in other media—not simply the text paintings, though they certainly presaged it, but the later ‘commissioned’ paintings (with their pointing fingers), and the early photographic series that played on visual syntax, rhyming, conjunctions and disjunctions—works which reached a kind of zenith in his works with film noir stills. His insight into the syntax of commercial narrative was uncanny. No one understood cut, composition, and dissolve like Baldessari (with a few possible exceptions, e.g., Godard). But Baldessari was moving towards a kind of metacritical art—preoccupied no longer with composition, but with the notion of composition; not time, but the notion of time (naturally using art itself—e.g., his proto-canon of contemporary art history). He was moving beyond Conceptualism before he was even through with it.

I had the opportunity to interview him for ARTILLERY in 2010 in conjunction with the Tate Modern-LACMA exhibition, Pure Beauty. By that time I knew him slightly; but Baldessari was not exactly an easy interview. Still he managed to be thoughtful and good-humored about the whole thing. (I was able to tease him about his then dismissal of art-fashion collaborations only a few years later when I saw him at Gemini G.E.L.—not long after he had executed a project for Saint Laurent—which he again took with good humor.) I took some issue at the time with his resurrection of that old chestnut from his text paintings for the show’s title. At that moment (only a decade ago?), it seemed disingenuous and almost simplistic. Now in 2020, it makes a kind of circle-game sense: not a pure beauty—after all, he saw the language of images in the fullness of their simultaneous humor and horror—but a beauty of the pure. Baldessari was after that kind of reduction, a kind of DNA of visual art, and perhaps the sublime itself. And in true Baldessari fashion, he wanted us to reconceive our notion of the sublime—a 100-proof distillation that might soothe and burn, dazzle and terrify all at once.

0 Comments