Your cart is currently empty!

Byline: Clayton Campbell

-

COMPASSIONATE VISIONS

The Los Angeles Poverty Department Brings Attention to Skid Row ArtistsThe Skid Row History Museum and Archive (SRHMA), founded by artist John Malpede and directed by Henriëtte Brouwers, is located at 250 South Broadway. It is a unique community art center, as well as a museum and archive for the historical displacement of people in Los Angeles due to immense income inequality. A critical part of the downtown arts ecology, SRHMA is a project of Malpede’s Los Angeles Poverty Department (LAPD), the first performance group in the nation made up principally of homeless people, and the first arts program of any kind for homeless people in Los Angeles. The publicly available archive speaks to the importance of place-keeping in a downtown community overlooked for decades. SRHMA affirms this through the art, activism and organizing of more than 1000 artists and creatives who have worked with LAPD for 35 years.

The SRHMA can be traced back t0 2008 when The Box gallery hosted an exhibition and series of performances and talks by LAPD, then provided them the resources to make and develop new work, which included an installation of 60 prison bunk beds for their 2010 project “State of Incarceration. Evolving from project-to-project work to a more expansive practice that required a physical space in 2015 with the founding of SRHMA.

Two major exhibitions of 2023 exemplify SRHMA’s goals to focus on a constellation of interrelated issues of continuing importance to Skid Row. These include gentrification and community displacement, drug recovery, the war on drugs and drug policy reform, the status of women and children in Skid Row, mass incarceration and the criminalization of poverty.

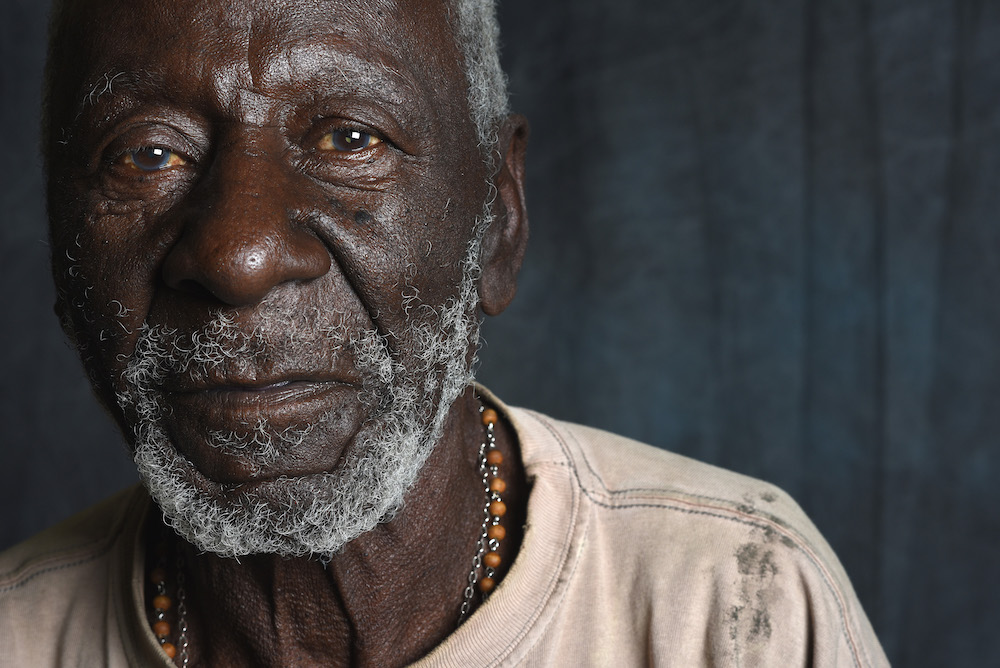

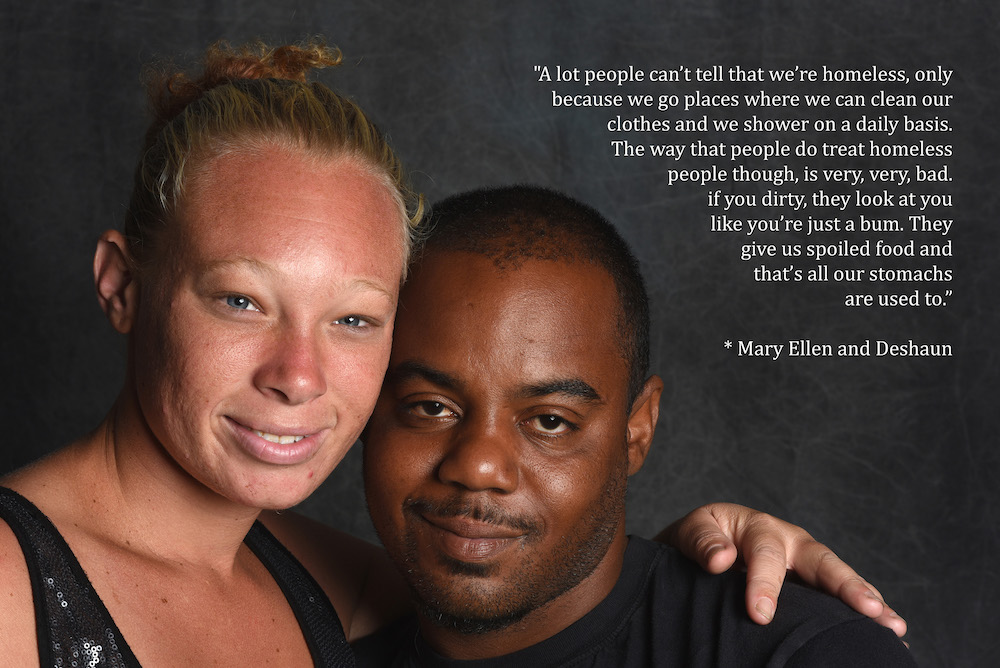

David Blumenkrantz, Mary Ellen and DeShaun, 2019. “Cosmology and Community: Networks of Liberation,” the first of SRHMA’s “Community Curators” series, introduced Charles Porter, project coordinator for United Coalition East Prevention Project, who has been working in the Skid Row Community since 1999. He collaborated with visual artists Dimitri Kadiev, Joshua Grace and Ellie Sanchez, each of whom responded to Porter’s language. Porter’s original poetry was written on the gallery walls and mixed with murals painted by the three artists. The poetry referenced his family history and origins in a historical free Black community in New Jersey, as cultural learnings on Skid Row. Throughout the gallery were participatory stations that had video, audio and a notebook containing both historical and contemporary documents.

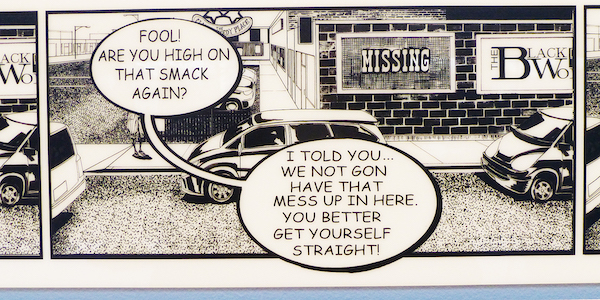

A four-person exhibition, “Enough is (never) Enough; Hard Truths and the People Who Live Them,” featured photographs and texts from the “One of Us” series by artist and educator David Blumenkrantz. He included works by four photographers who have experience with homelessness: Bobby Buck, Cleta Felix-West, Lelund Hollins and Ian Storm. The exhibition, viewed by the artists, is an expression of growing frustration with the slow pace of reform and change that leaves the well-being of thousands of Angelenos in a state of limbo and generates an alarming death toll. The latest homeless count reveals a 10% increase in homelessness in LA this year alone. According to Brouwers of SRHMA, “The situation for the homeless is worse than ever now.” This is due to city neglect, lack of political agency and the terrible effects of fentanyl flooding the drug market.

In 2021, LAPD again joined forces with The Box in the “Compassion & Self-Deception Project.” It dared to imagine a downtown that attracts people who value the wisdom and compassionate practice exemplified by Skid Row residents and workers. Next time you are at Hauser & Wirth, The Broad or MOCA, remember that SRHMA is just a stone’s throw away; go pay a visit.

“

Cosmology and Community: Networks of Liberation,” installation view. -

Racial Reckoning

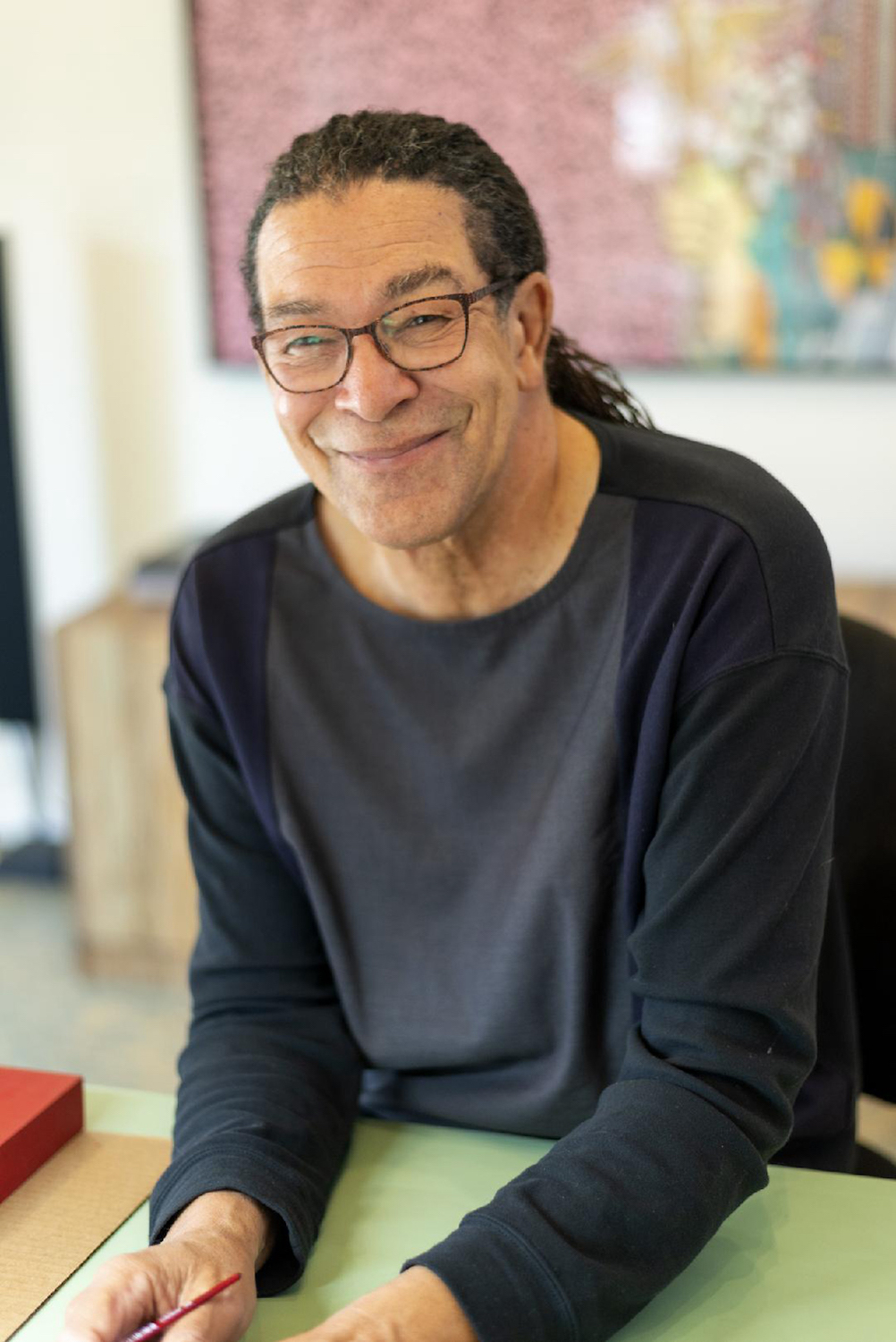

Mark Steven Greenfield Illuminates the Black ExperienceIn 2020, Mark Steven Greenfield unveiled a new body of work, “Black Madonna,” followed by “HALO” in 2022, both at the William Turner Gallery in Santa Monica. Gallery owner William Turner told me in an email that the “Black Madonna” show was a natural progression of Greenfield’s career of investigations into race and racial identity. “It was a sensation when we opened it in the fall of 2020,” Turner says. “It was purely coincidental, but after the summer of George Floyd and Black Lives Matter, our show became a catalyst for people discussing these issues.” Turner witnessed viewers staying nearly an hour in the gallery studying Greenfield’s intricate paintings. “We have never had a show that had that kind of depth of impact.”

Mark Steven Greenfield Portrait, Photo Credit Tony Pinto A native Angeleno, Greenfield is receiving well-deserved recognition. Besides being a full-time artist, he has had an

extraordinary career as a significant cultural producer in the roles of arts administrator, curator, juror and teacher in Los Angeles. Like many artists who have a hybrid career in the arts, Greenfield worked as Art Center director at the Watts Towers Arts Center and director of the Los Angeles Municipal Gallery for the Cultural Affairs Department, City of Los Angeles. His associations with over 25 cultural and service organizations are a testament to his ethos of service and support for artists and community.

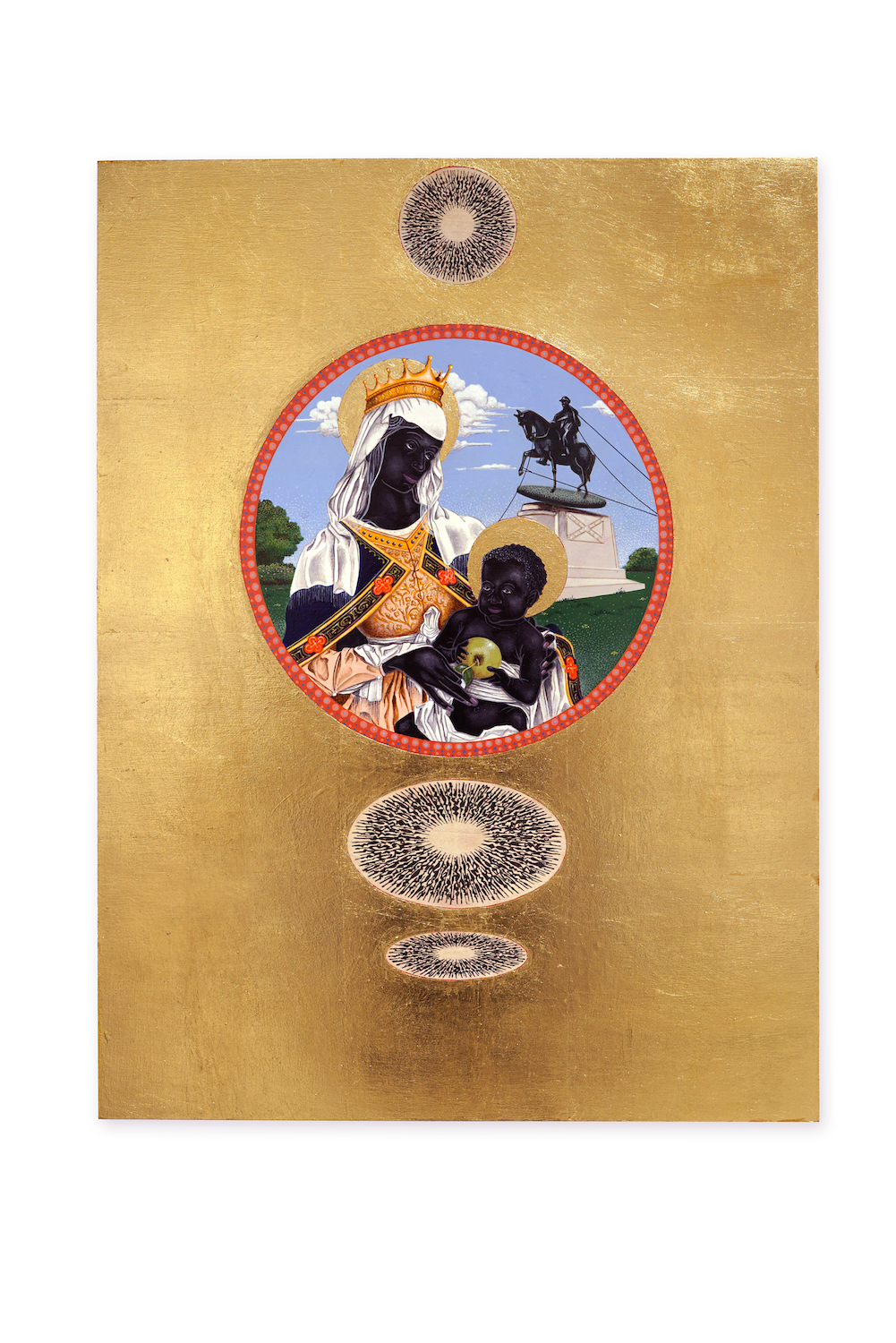

Toppling, 2020, Acrylic and Gold Leaf on Wood Panel, 24” x 18” Raised a Catholic and a long-time practitioner of meditation, Greenfield infuses his work with allusions to ritual, ceremony and spirituality. Painting images of Black and brown persons on gilded panels in a meticulous narrative, representational style, “Black Madonna” and “HALO” become symbols of empowerment and unification. When Greenfield alludes to the protective and healing purposes of traditional religious icon art, he suggests his work is also meant to offer similar forms of protection. Both his series clearly respond to the killings of African Americans by the people who are supposed to keep our communities safe. Greenfield says of his recent paintings that they “conjure up memories of the church and the reverence once paid to statues and images of saints,” but are now redirected to those who have taken up the struggle for social justice. He adds, “I made the choice of honoring those little known heroes, martyrs and personages from whose stories we might gain strength.”

Escrava Anastacia, 2020, Acrylic and Gold Leaf on Wood Panel, 24″ X 24” Greenfield’s art practice explores and illuminates the Black experience, focusing on the effects of stereotypes on American culture. Always provocative in an unexpected way, his work stimulates a much-needed and often long-overdue dialog on issues of race. His recent summer exhibition, “HALO,” has created another conversation. While “Black Madonna” played with the idea of role reversals—revering and worshiping a Black Virgin Mary and a Black Baby Jesus as symbols of love; what if white supremacists were the victims instead of the oppressors—“HALO” evolved as a next natural progression, highlighting historical Black figures. They have been chosen from the period of the slave trade during the 1400s–1800s. He wants his subjects—often legendary in their time yet now overlooked—to be rediscoverd. Greenfield’s use of gold as a material connotes value and importance, but also currency. Most of the people depicted in the series were enslaved and treated as commodities. His figurative painting is particularly striking. Greenfield explains,“The figures are rendered in ‘ultra-black’ in keeping with their political designation and not so much for their degree of melanin. It is the element in these paintings that unifies, regardless of association, wealth, class or prestige.” Almost all of the paintings have circular glyphs, a visual device that is a through line in much of Greenfield’s work. These evoke the mantras he uses as a vehicle in his daily meditations.

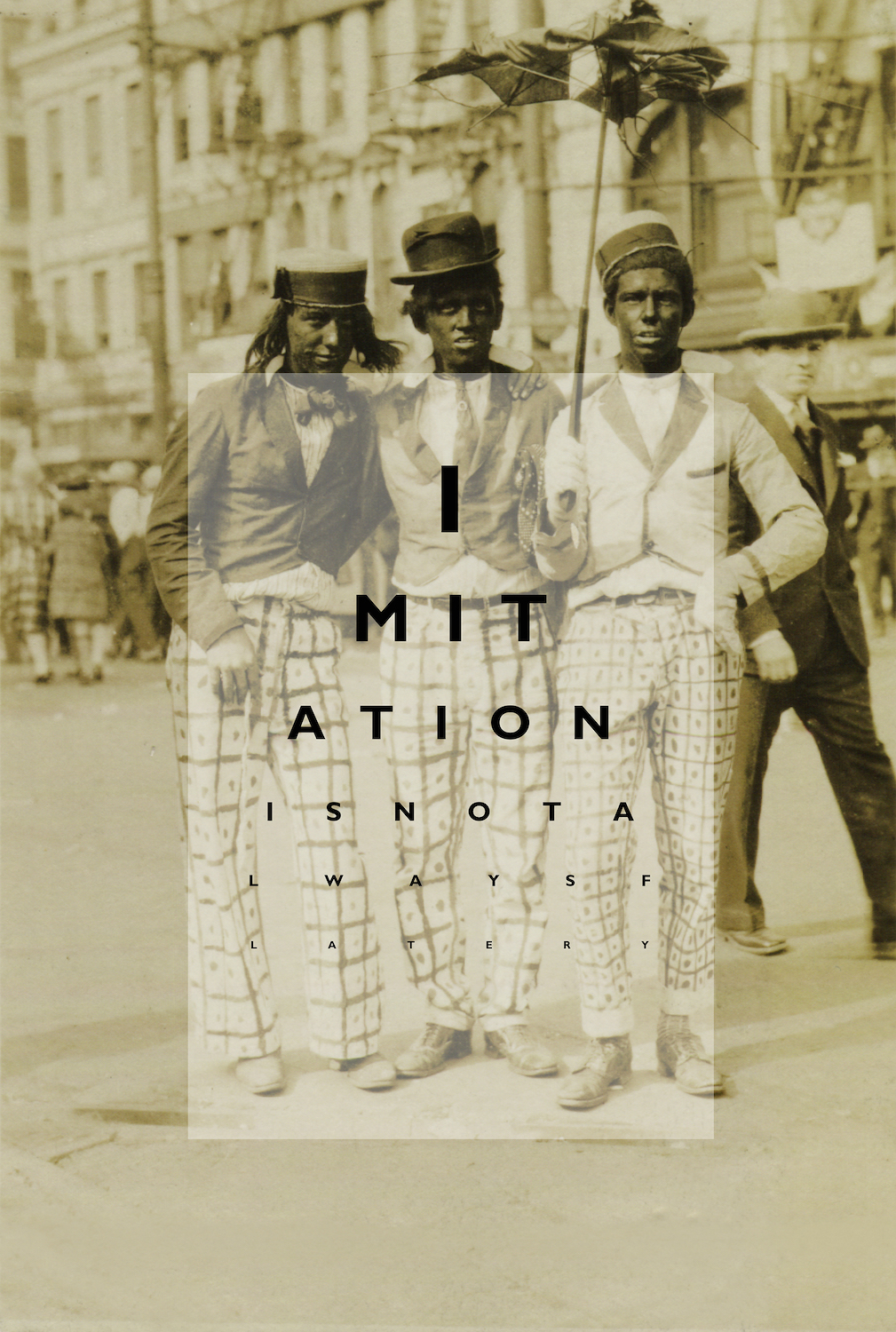

Lesson, 2002, Ink Jet Print, 37″ X 28″ In Greenfield’s work, each series has developed its own stylistic approach. For example, his 2007 exhibition “Incognegro,” at the 18th Street Arts Center, consisted of appropriated photographs. They are mainly of white people in black face, who in turn were appropriating African American culture. For this body of work, he made Iris prints and lenticular photographs. The mirror effect of lenticular photography heightened Greenfield’s intention to expose and dramatize the complexities surrounding issues of race, identity and perception. With the photos of turn-of-the-century black-face performers he superimposed a subversive message that looks like a optometrist’s office eye chart. They contain direct, challenging statements and questions about race and identity. “Incognegro” caused a stir about the use of Black stereotypes and whether they were helpful or hurtful. Mark says of this experience, “Work dealing with the indignities associated with black face has always been a messy proposition.” He believes that black-face images have haunted communities of color for a long time. His intention with this series was exorcising the demons that these images have conjured up; without that, he says, “We’ll never really be free. “Incognegro,” while problematic in 2007 for some segments of the Black community, is starting to impact whites, compelling some degree of introspection on their part. It has brought into focus the responsibilities associated with social justice and allyship. Both “Black Madonna” and “HALO” expand this conversation and engagement with a larger audience that is willing to listen and learn from the social reckoning occurring globally and locally. At a moment when many younger artists of color are gaining national attention for their identity-based work, Greenfield has always been creating conversations about racial reckoning, both as an artist and cultural producer. His unswerving commitment to self-examination and community has made him a change-maker in the best sense of the word.

-

Letters in Exile, No. 6

By Maria AgureevaSince March I have edited Letters in Exile with Maria Agureeva. Artillery generously offered Maria and other artists who had fled Ukraine and Russia an important platform from which to express their feelings, voice their grief and protest, and to share stories of courage and compassion.

There are two books I have recalled while editing. In one, by the diplomat and historian George Kennan, he expressed in the 1960s that the two most important issues to be solved in our life time are climate degradation and nuclear proliferation. As we see in Russia and Ukraine, they are inextricably linked with the ongoing state sponsored violence. The other book, The March of Folly by historian Barbara Tuchman, looks at the avoidable but mindless paths to war, ecological catastrophe, and destruction of civilizations, even though the people of those time knew better. It seems to me there is a dominant strain of reactionary violence in collective human behavior that is deeply disturbing.

The words of the Buddhist activist Thich Nhat Hahn helps show me a sane way forward; “To prepare for war, to give millions of men and women the opportunity to practice killing day and night in their hearts, is to plant millions of seeds of violence, anger, frustration and fear that will be passed on for generations to come. We know very well that airplanes, guns and bombs cannot remove wrong perceptions. Only loving speech and compassionate listening can help people correct wrong perceptions. The practice of peace and reconciliation is one of the most vital and artistic of human actions.” —Clayton Campbell, Editor

Maria Agureeva

I want to end Letters in Exile for now with the release of a sixth installment, #NoWar. To all of you who have followed my blog, from my heart I wish to thank you very much; to the long list of everyone who took part in previous blogs, helped my family leave Russia, and especially to the artists who have spoken their truth through Letters in Exile. Because of this unexpected and incredible support, I will be back in Los Angeles soon, and will resume my life there. There were moments I didn’t think this would happen, and now I look forward to how my practice will unfold, informed by my experiences.

I spoke with Digital Art Month’s curator Jess Conatser to highlight artists creating AR and video artwork that inspires peace and stands for #NOWAR in Ukraine. The festival is organized and curated by Elena Zavelev, Andrea Steuer of CADAF & Jess Conatser of Studio As We Are.

For AR please use your phone to access them.

Hermine Bourdin

Dance For Peace (Augmented Reality- open on your phone to interact) https://www.instagram.com/ar/314068410688765/

Dance for peace is the performance of the French dancer Eugenie Drion re-transcribed on one of my sculptures using MOCAP.

Yamid Botina

Invisible, Video, 1:01 minutes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cg70rHEVYo4

Botina’s approach to the conflict in Ukraine, based on the things that cannot be destroyed.

Maria Agureeva

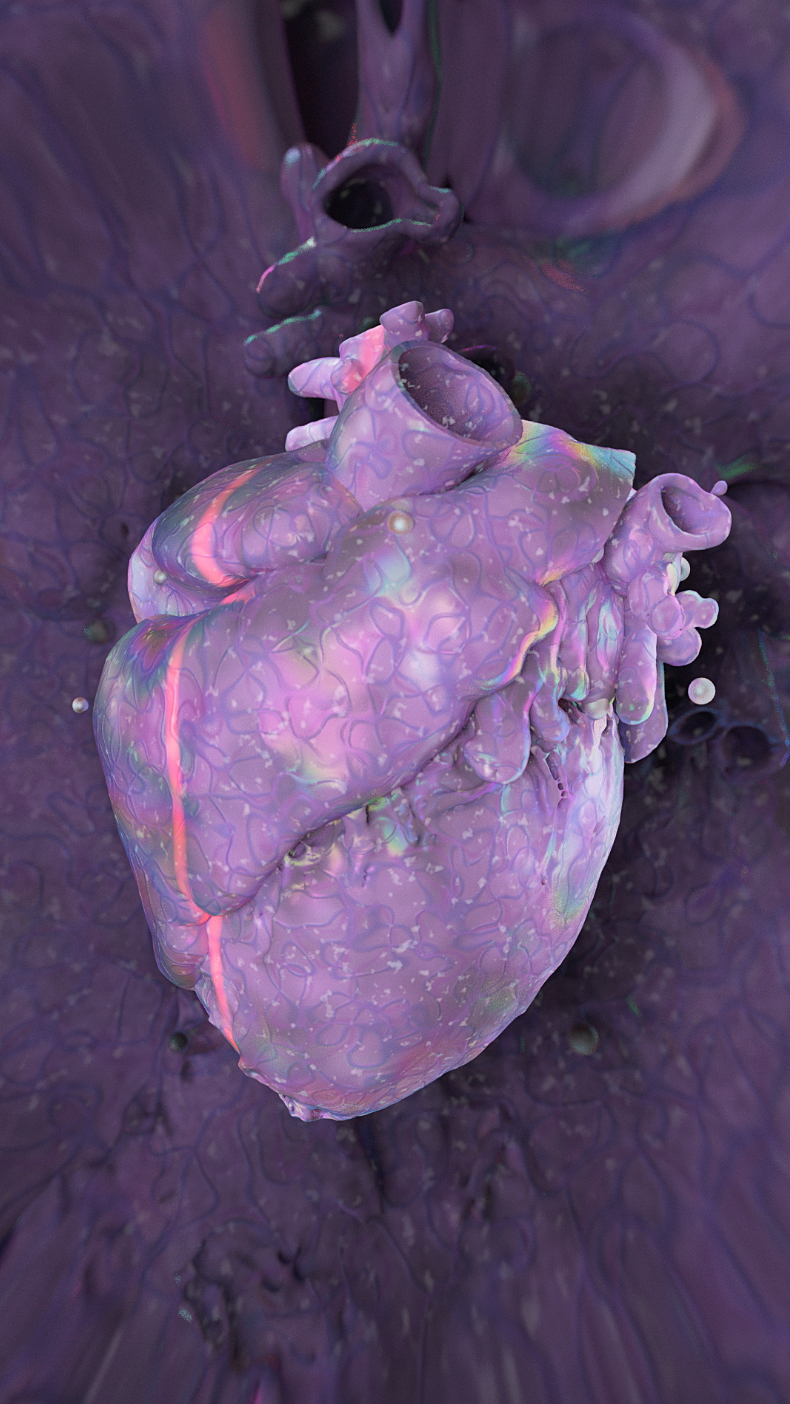

The First Universe, Video, 45 seconds, Sound Art Dario Duarte Nunez. https://www.instagram.com/tv/Cda7_ERAViH/?utm_source=ig_web_copy_link

How quickly we forgot about Love. How often we perceive the heart as only an organ, as a motor that carries through the body, along with blood, gunpowder of war, fear, hatred, confusion and other toxins.

But our hearts are so much more. It is an object that exists simultaneously in billions of universes, where Love resides— the very first of them.

Clayton Campbell

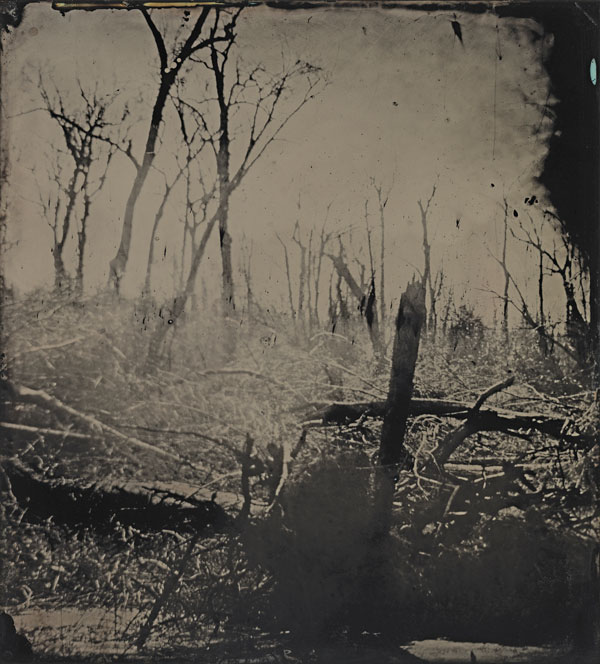

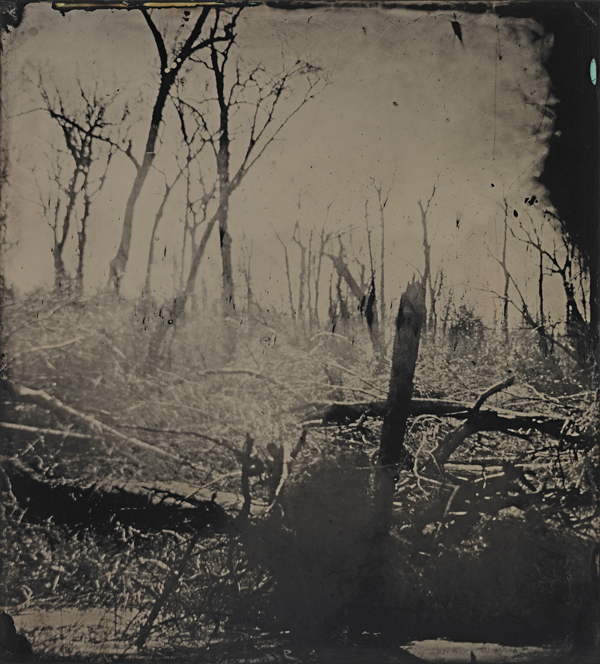

Ghost Ships (photographic print, 2022, 66” x 88”), March 2022 These days a density of fractured images have arrived in my disturbed sleep.

Despairing of the inevitability of Men; their fogs of war, addictive cravings for spilling blood, sexual subjugation, unscripted power stripped of knowledge, wisdom, and compassion,

We travel onward through the dark night of the soul in our Ghost Ships.

Jullian Young

Caged in Red (Augmented Reality- open on your phone to interact) https://www.instagram.com/ar/5230824633642795/

This artwork places you inside a crumbling red cage surrounded by bluebirds whose yellowish tint is only cast in light

Kushtrim Juniku

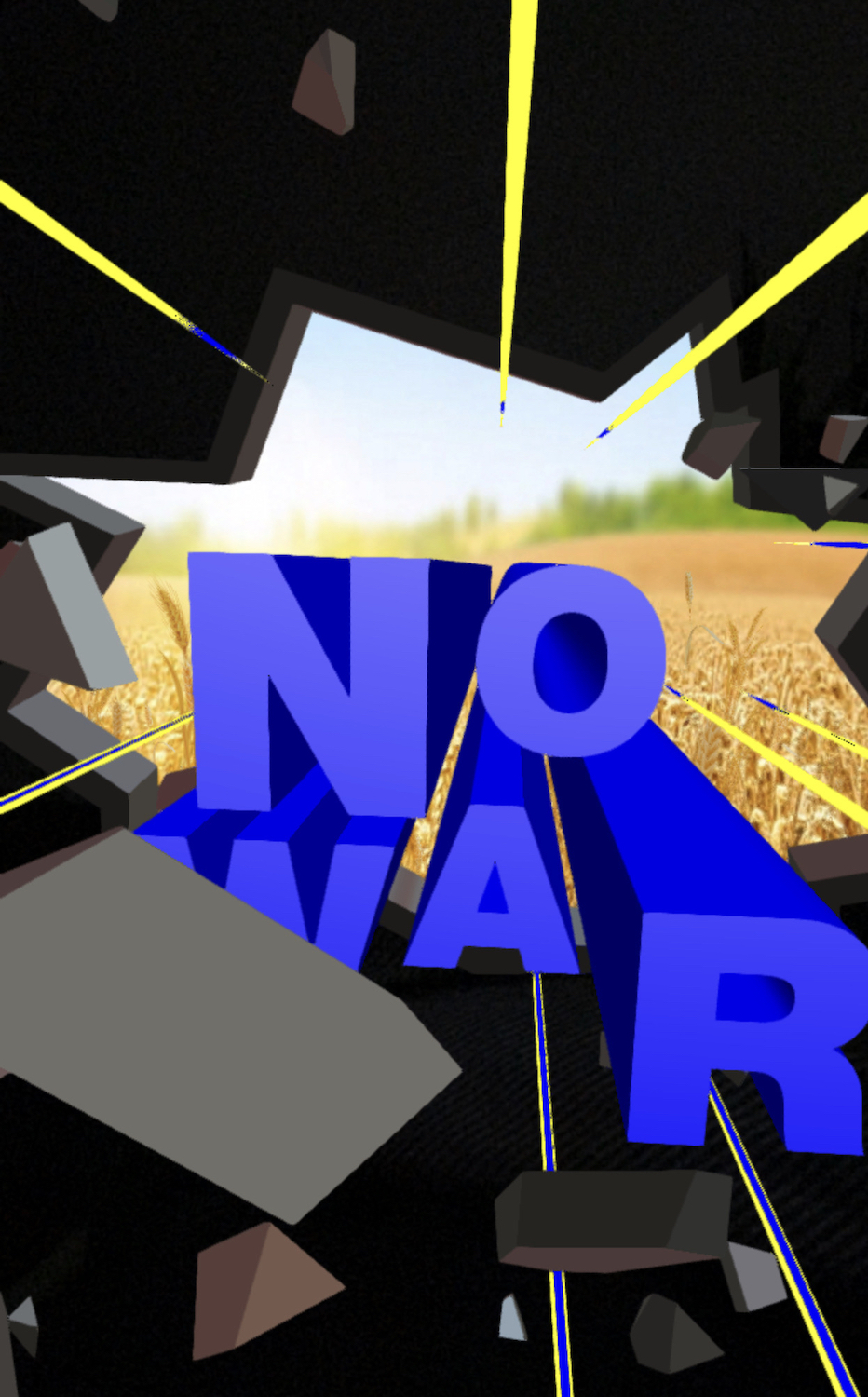

No War (Augmented Reality- open on your phone to interact) https://www.instagram.com/ar/511333743820354/

NO WAR is an AR effect that inspires to speak up against the war in Ukraine .

Zoran Poposki

Peace Piece, 2022, animated video generated by AI in collaboration with artist and director Polyptech. 4K video, sound, 1:00 minute https://vimeo.com/697821931/cbc89c0045

“Peace Piece” is a short animated video generated by artificial intelligence (AI) in collaboration with award-winning contemporary artist and director Polyptech.

The visuals are a series of AI-generated artworks created by Polyptech through text-to-image synthesis utilizing a neural network. The neural network has been trained by Polyptech through thousands of iterations to generate visuals based on a string of keywords associated with peace, such as pacifism, no war, harmony, demilitarization, empathy, love, human rights, social justice, sisterhood, humanity, love, etc.

The lyrics in the video represent an AI-generated poem co-written with Polyptech, based on Emily Dickinson’s reflection upon peace and belonging, “I many times thought Peace had come”. The AI uses a generative text model developed by Open AI, leveraging machine learning and deep learning to achieve the generation of natural language.

The music in the film is a generative sound piece created by an AI music algorithm.

Editor’s Note: If you would like to donate to Ukrainian relief efforts, you may make a direct contribution to the Global Giving Ukrainian Relief Fund at this link. Or please donate to a charity of your choice that will assist the people of Ukraine.

https://www.globalgiving.org/projects/ukraine-crisis-relief-fund/

-

Letters in Exile, No. 5

By Maria AgureevaArtists are experiencing a sense of gratitude for the unexpected support and basic kindness shown to them. In the midst of exile and displacement, often the best of humanity reasserts itself.

As Maria says in her fifth blog, “So many of my friends and colleagues who were also forced to leave Russian and Ukraine tell incredible stories. I asked some artists to share their stories.”

Two persons, Maxim Zmeyev, a photojournalist; and a young musician, Yaroslav Dimov, share their stories. —Clayton Campbell

April 20, 2022

Recently I was at a reception at the Czech embassy and for almost 1.5 hours the discussion was only about the war. Secular meetings become like “war councils.” People raised issues that are now worrying everyone: how such an event is possible in the 21st century, how to help Ukraine, or will there be a nuclear incident as the war expands? However, several speakers said that now it is an important task to support the artists, journalists or dissident musicians who do not support the existing regime in Russia.

Before I fled Moscow, I was isolated, alone. I feel such incredible support now! I have never received so much help from friends and strangers from other countries. I had believed that people’s humanity in the Metaverse era was in short supply. Yet now a hundred thousand acts of unselfish generosity have awakened people into a spirit of gratitude. Everyone helps each other, and I have been deeply touched.

When the war began, friends stepped up, finding a residence for me and my daughter in Berlin. An American foundation unhesitatingly gave me a grant that has allowed us to survive. And miracles continue to happen in my life. This gives me hope not to give up and continue to engage in art, to which I have dedicated my entire conscious life.

Action in front of the Russian Embassy in Vilnius against the violence of Ukrainian women by Russian soldiers. Photo: Edvard Blaževič / LRT So many of my friends and colleagues who were also forced to leave Russia and Ukraine relate incredible stories. I asked some artists to share their stories:

“My name is Maxim Zmeyev, I am 35 years old and a contemporary artist and photojournalist. I was a photographer for Reuters, as well as a freelance photographer for the AFP and independent media in Russia. Russian troops attacked Ukraine on February 24 on the orders of Russian President Putin. Russia’s aggression continues to this day. As I write this letter the Russian military continues to destroy Ukrainian cities and kill Ukrainians. This is a fact and from March 4, 2022 the Russian Federation could see up to 15 years in prison for disseminating or discussing this fact. On March 5, I flew to Istanbul where I am now. I’m looking for an opportunity to move to Europe or America and am in contact with Journalists Without Borders—who are trying to help me. I hope I will have the opportunity to live on. I have a friend who is a French journalist, Anne. She is helping me a lot right now and gives me hope. It’s very important to feel that if you’re from Russia, it doesn’t mean that the whole world hates you. For people like me who are against the war, it gives hope that peace can come.”

Max Zmeyev, Red Mirror (project in progress), 2022

Photo collages from “Red Mirror” series consists of photos taken in the video game which takes place in Russian/Soviet reality. These games were made by developers from countries that were part of the USSR and/or Soviet Empire. These collages also contain elements of documentary archive photos of the USSR.“My name is Yaroslav Dimov, I am 18 years old, from Kiev. All my life I have tried to give people positive emotions through music. In October 2021, my friends and I created a group and we intensively gave concerts in popular venues in the capital, where many came to hear our work. Our goal was for people to learn to listen to each other. On the third day of the war, I miraculously managed to leave my home and get rid of the hellish sounds that Russian rockets made, I just wanted to live. The road to Europe was for me a leap into the unknown and a step towards a new life. In Berlin, My family and I were treated with understanding, care and support. Kind people helped us with a place to stay and every day they offer their help; it’s cool that they consider us their friends. Our neighbors provided a few musical instruments and space to practice my music. Here I met musicians from Ukraine and we managed to participate in several charity concerts in support of our country. We believe that goodwill overcome evil and music will help this.”

It seems to me that against the backdrop of this ongoing madness, we should unite and help each other—the only way to endure. The whole world now feels vulnerable and only unity can help to survive. Our strength is in unity and the ability to hear each other.

As I prepare to leave Berlin at the end of the month, nothing is certain. The war could ripple through more countries, creating widespread financial ruin and devastation. Or, it might stop, and the world will blossom with the spring.

Yaroslav Dimov, personal archive, Kyiv, 2021 To be continued…

—Maria Agureeva

Editor’s Note: If you would like to donate to Ukrainian relief efforts, you may make a direct contribution to the Global Giving Ukrainian Relief Fund at this link. Or please donate to a charity of your choice that will assist the people of Ukraine.

https://www.globalgiving.org/projects/ukraine-crisis-relief-fund/

-

Letters in Exile, No. 4

By Maria AgureevaAs Maria was working on Blog 4, I happened upon an article about photographer Edward Burtynksy, who is of Ukrainian descent and still has family there. He was scheduled to photograph in Ukraine this year for other reasons than the war. His work has been postponed. He said of what is happening in Ukraine and Russia, and that Maria’s blog speaks directly to, “Unbelievable, the amount of hate and trauma that’s being inflicted. [Putin]’s destroying the future of a whole generation of Russians and traumatizing the whole country of Ukraine. It’ll take generations to heal.”

Artists respond to war situations in various ways, as anyone would be. When undergoing stress and trauma caused by dislocation, loss of statehood, livelihood, physical harm and perhaps death, people are changed physically and emotionally. Overtime, personality and values are taken over by trauma responses, making living life so difficult because all trust is gone. What is happening in Ukraine and Russia is a cautionary tale for free-minded people, seeing how easy it has been for personal freedoms to be taken away by an autocratic, conservative government. Maria suggests that artists can, in spite of everything that may happen to them, find the way back again to a full embrace of life. —Clayton Campbell

Lviv, Ukraine–March 26, 2022: Concert near Lviv National Opera. Photo: Ruslan-Lytvyn April 15, 2022

The mission was impossible.

Since the ’90s, when the first contemporary galleries appeared in Russia, art began to actively develop and be included in the international context. After 2014, when Russia annexed Crimea, everything changed. Perhaps we created our own bubble of illusions, inflated more and more as Russian artists found success. What we thought we were building, a free-minded cultural community, did not transfer to the vast majority of Russians. They had no interest in our values and creative pursuits.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, restrictive regulations on artmaking were canceled and for the next 20 years artists could fight for the freedom of their art without fear of punishment from the state. Integration into the global cultural space supported this illusion: that Russian art could be free. This is the era I grew up in as an artist. But another fate was prepared for us.

There was some change in those two decades. The influence of contemporary art helped to penetrate a historically unfree land. Surveys from 2021 show that at least 30% of the Russian population put freedom as their first priority and do not support repressive actions by state authorities. Yet this minority has been silenced as artists are now squeezed out of their country.

This liberal change of sensibility, especially in younger generations, threatened the government. Over the past five years censorship in Russia has returned. High-profile artists have been publicly punished. Kirill Serebrennikov, born in Ukraine, is one of the most prominent theater directors in Russia. He spoke out against the Russian annexing of Crimea. As a result, his apartment was raided shortly after. He was sentenced in June 2020 to a three-year suspended prison sentence and was also issued a fine over trumped-up charges of embezzlement. A Moscow court canceled the suspended sentence after questioning the filmmaker twice last month. The director left Russia two weeks ago and is residing in Germany.

Still from the film Leto, Director Kirill Serebrennikov

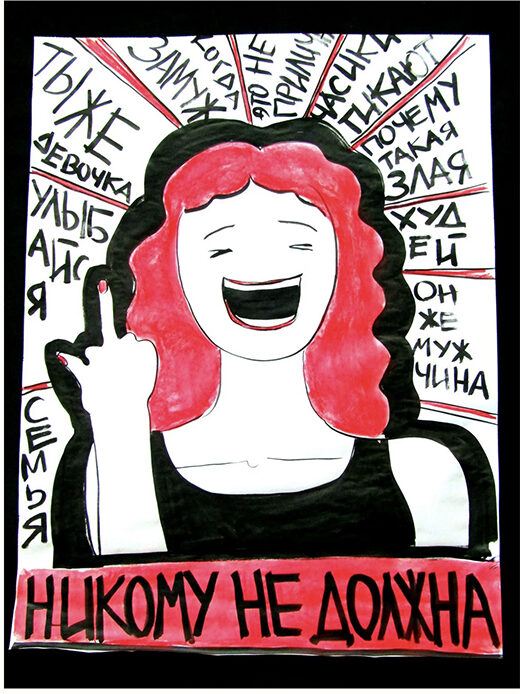

Still from the film Petrov’s Flu, Director Kirill Serebrennikov In another example of public shaming, feminist artist and LGBTQ+ activist Yulia Tsvetkova is on trial in Russia, facing charges of disseminating pornography based on her artwork featuring the naked female body. She was arrested in November 2019 and was forced to pay two fines under Russia’s notorious “gay propaganda” law. She remained under house arrest until March 16, facing up to six years in prison if found guilty of illegally producing and distributing pornographic materials on the internet. The current case has terrible implications for the future of women’s rights in Russia, as it marks the first time an activist has faced criminal charges to produce feminist art.

Yulia Tsvetkova and her viral body-positive drawings A Woman is Not a Doll. Photo: Anna Khodyreva

Yulia Tsvetkova, Untitled, 2018. Text in red- “You don’t owe anyone anything” Around her are comments like “smile, lose weight, family, etc.”

Yulia Tsvetkova, “My body is not pornography!” reads the protestors placard. “Is this an Article 242?” wonders the policeman. Article 242 of Russia’s Criminal Code criminalizes the creation and exchange of pornographic materials. Image ©: Yulia Tsvetkova Authority of most kinds has never trusted art. Art makes it possible to think critically. People who contest various forms of power and control are uncomfortable to the status quo. We are viewed by Authority as uncontrollable. Like a mindless machine the State can only suppress, alienate or kill us.

In the supposed socialism of Russia, Dmitry Medvedev (former Russian president) recently stated that Russian culture will not close itself off from the world, but will focus on “adequately minded people”, those who share and support their position. This is about staying in power

Four years ago, when I left for Los Angeles, I was able to feel the whole abyss that still separates the contemporary art of Russia and other free countries. It has become, I fear, an unbridgeable chasm.

Many young people were among those out demonstrating in Russian cities. Here, a young woman in St. Petersburg is detained by officers. (Photo: Dmitri Lovetsky/The Associated Press) The liberal change of sensibility in the last 20 years, especially in younger generations, threatens the government. I can definitely say that the generation of my daughter, who is now 16 years old, is completely different. They have a sense of empathy, lack of fear, and think freely. More than 400 teenagers were detained in Moscow in February and March at anti-war rallies. As a result, on February 24, 19 protocols were drawn up to punish a perceived failure by parents to fulfill their obligations to raise minors, due to the participation of children in rallies. They include fines and possible deprivation of parental rights in case of repeated detention.

Russian President Vladimir Putin and Dmitry Medvedev attend a meeting with members of the government in Moscow, Russia January 15, 2020. Sputnik/Dmitry Astakhov/Pool via REUTERS/File Photo. They warned the United States on Wednesday that the world could spiral towards a nuclear dystopia if Washington pressed on with what the Kremlin casts as a long-term plot to destroy Russia. It is beginning to seem that the war will continue for a long time; the wreckage of Ukrainian museums and concert halls will smoke in ruins for more years; the Russian cultural spaces supporting truly free art will return not soon. Russian President Putin recently spoke live on Russian TV and voiced a phrase popular in his circles: “The war between Russia and the United States will continue until the last Ukrainian.”

It’s hard for me to imagine now how artists will come out of this meat grinder. It may only be possible to truly talk about this only after the end of the shooting. What Ukrainian and Russian artists are now experiencing will sooner or later be embodied in their work. This will be a whole stage in the global cultural agenda. And it shouldn’t be lost, blurry. This should be accepted, comprehended as part of a new culture, even more free!

It seems to me that most artists I am meeting and hearing from have quickly developed a different attitude to their work. I am rethinking my past work and the topics covered. There is a greater sense of responsibility. The topics of ecology, gender issues, our future, have not lost their relevance, but now my focus has shifted, everything becoming much sharper and more subtle.

I invite other artists to share with me what they are experiencing today and I will publish it on my blog.

—Maria Agureeva

Editor’s Note: If you would like to donate to Ukrainian relief efforts, you may make a direct contribution to the Global Giving Ukrainian Relief Fund at this link. Or please donate to a charity of your choice that will assist the people of Ukraine.

https://www.globalgiving.org/projects/ukraine-crisis-relief-fund/

-

Hugo Hopping and The Winter Office

Nature As InfrastructureI became aware of LA artist Hugo Hopping in 2009, when his conceptual work appeared in the exhibition “Post American L.A.,” curated by Pilar Tompkins Rivas for the 18th Street Arts Center in Santa Monica. Since then his trajectory has taken him to base his practice between Los Angeles and Copenhagen, where he co-founded The Winter Office (TWO) with Johanna Ferrer Guldager. TWO is an experimental and professional group of artists, curators, architects, designers and social scientists, who are exploring artistic and design interventions looking to uncover emerging solutions for a sustainable urban and natural infrastructure.

TWO’s theoretical and creative approach to architecture, urban planning and art is deeply enmeshed in the climate challenges of a warming world. Through a process of collaborative experimentation, TWO explores problem-solving through idea-sharing and research workshops, including rising housing inequality, economic displacement, houselessness and environmental disaster. Hopping, with members of TWO, were back at 18th Street in 2019 for a residency. They developed a study of the cultural landscape of the surrounding urbanity and communities, including climate gentrification. TWO also presented at the Armory Center in Pasadena, with “Non-Perfect Dwelling,” a visual environment where urgent approaches to dwelling and cohabitation could be imagined and planned.

Rewildering Holographic Weeds, TWO, 2020

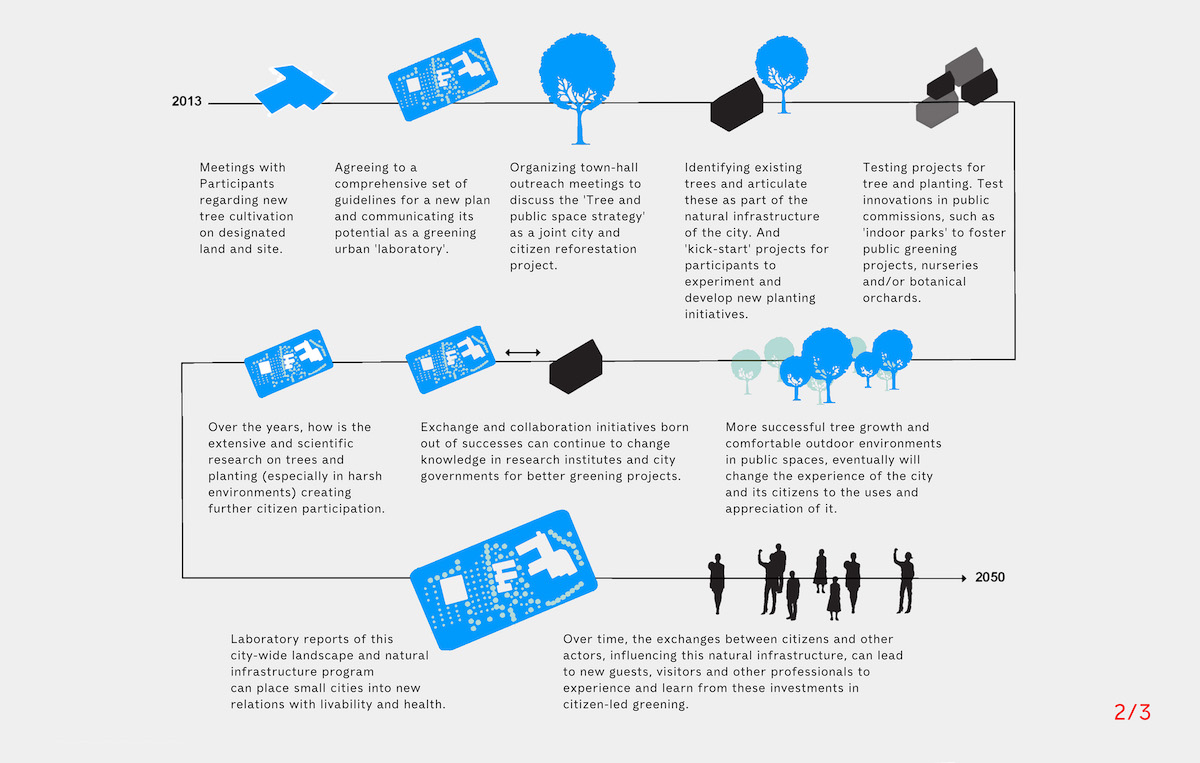

Cover for the new publication, Nature As InfrastructureAfter quarantine in Copenhagen, Hugo Hopping is back in LA, doing advance work for TWO’s project, Nature As Infrastructure. Last year it was road-tested at the European Biennial Manifesta 13 in Marseilles, France. Their project is researching how to re-establish new connections to nature, rethinking a renewal of society, and inspiring the design of future public spaces by asking how to reintroduce nature into cities. Following a methodology they describe as the “creative practice of spatial justice,” TWO navigates from discourses of power and human survival to conversations of collaboration and thriving.

TWO’s and Hopping’s practical-theoretical research is being conducted in Frogtown’s Elysian Valley and will be a continuation of the forthcoming Nature As Infrastructure publication. It documents and describes their work on designing forests as a program element leading to the establishment of natural infrastructure. Hopping says, “Frogtown is a very special area walled by the 5 Freeway and the LA River, near urban parks and a sizable number of trees. However little or no sound walls or the use of trees to absorb the plastic and CO2 pollution is in place. The lines in the diagrams for the project suggest the interplay between full-grown tree canopies and shared cultivation models mixing public and private land to build a powerful natural infrastructure. Our study aims to understand this area in full in order to generate a near-future proposal that can involve public and private participation to help implement most of our suggestions.”

This second diagram image relates directly to what TWO plans to further theorize for Elysian Valley and that they hope citizens can buy into in practice and for full implementation. Perhaps a precursor to TWO’s work is articulated in Suzi Gablik’s thesis, The Re-Enchantment of Art (1991). It promoted reconstructive art practices with a basis in real-world solutions. TWO’s work also brings to mind recent LA participatory environmental projects that were artist-centric. Mel Chin’s The TIE that BINDS: MIRROR of the FUTURE, a water conservation art project, was part of Los Angeles’ 2016 Public Art Biennial. Chin’s project began at the Bowtie, a parched stretch of land adjacent to the LA River in Atwater Village, where eight sample gardens were created. The project envisioned drought-resistant gardens planted throughout LA, reflecting a climate-appropriate collective-future landscape. Another inspirational project was by artist Lauren Bon. Her Not A Cornfield was a 2005 art project that transformed a 32-acre industrial brownfield into a cornfield for one agricultural cycle. It was a wonderful breath of optimism and boosted public awareness that this area could be more than another industrial site, expediting the process of turning the site into a State Historic Park.

Nature As Infrastructure, along with the launch of TWO’s publication about the project, discusses the importance of generating higher standards of spatial justice through the design of urban forests, along with new roles of citizen participation. LA as a laboratory for environmentally based social practice art is unique because the city embodies many of the climate change and climate justice extremes and challenges we face. Artists and thinkers like Hopping and TWO, who address these issues proactively, are on the leading edge of an evolving, collective 21st-century art and social science practice.

An advance look at TWO’s forthcoming publication can be seen at https://rssprss.net/product/nature-as-infrastructure-two/

-

A Reckoning: Monument Lab, Joel Garcia, Ken Lum, and Paul Farber

Monument Lab, based in Philadelphia, and founded by curator Paul Farber and artist Ken Lum, is a public art and history studio whose moment has arrived. Defining monuments as “a statement of power and presence in public” they’ve intersected with the active national movement to remove monuments and statues that reflect the racist history of the United States. Their values reflect progressive antiracist, de-colonial, feminist, queer, working class, ecological, and social justice perspectives working to inform our understandings of U.S. history and its monuments. In just a few years they have expanded from local projects to having a national and international profile. They just received a $4 million grant as part of Mellon Foundation’s $250 million Monuments Project. Monument Lab’s grant will support the production of a definitive audit of the nation’s monuments. This will help identify the stories and narratives that have been ignored and do not exist in monument or memorial form. They will be opening ten field research offices, one of those offices may be in Los Angeles next year.

This past year has stretched our capacity to imagine what comes next, with the confluence of the pandemic, a heightened movement for racial justice, and an election with its caustic aftermath. Throughout we have seen offending statues and monuments pulled down around the United States as well as Europe. Questions are unresolved about how to contextualize these faded, flawed icons. While some want to see problematic statues reflective of our racist past disappear, others would prefer for them to stay, so long as placards and descriptive texts that contextualize and educate the public surround them. Beyond this however, how do we then begin to memorialize our country’s many ignored and suppressed histories in their place?

Ken Lum is the Artistic Director of Monument Lab, but also a prolific Canadian visual artist, writer, and teacher of Chinese descent. He has produced numerous powerful public works challenging established worldviews about how we see ourselves. Artist Hans Haacke says of Ken, “ Over many decades he has pointedly challenged ruling classes in many regions of the world, religious suppression, racism and other horrors. Driven by a deep sense of humanity, his engagement, backed by a wide knowledge of history and pertinent literature, is reflected in his thoughtful writings on art and life.”

Next year Ken will be having an exhibition at Royale Projects in Los Angeles. His new works are photo-based images screen-printed onto mirrors. They make a strong commentary about bias in our popular imagination, cultural legacy and received histories. At sizes up to 6 by 6 feet, works like Anna May Wong, Batista, or United States at Night, cover a range of his social justice concerns by looking at Asian American stereotypes, U.S. foreign interventions, and climate change.

Ken Lum, Anna May Wong, screen print on mirror, 6’ x 6’, 2020

Ken Lum, Batista, screen print on mirror, 6’ x 6’, 2020

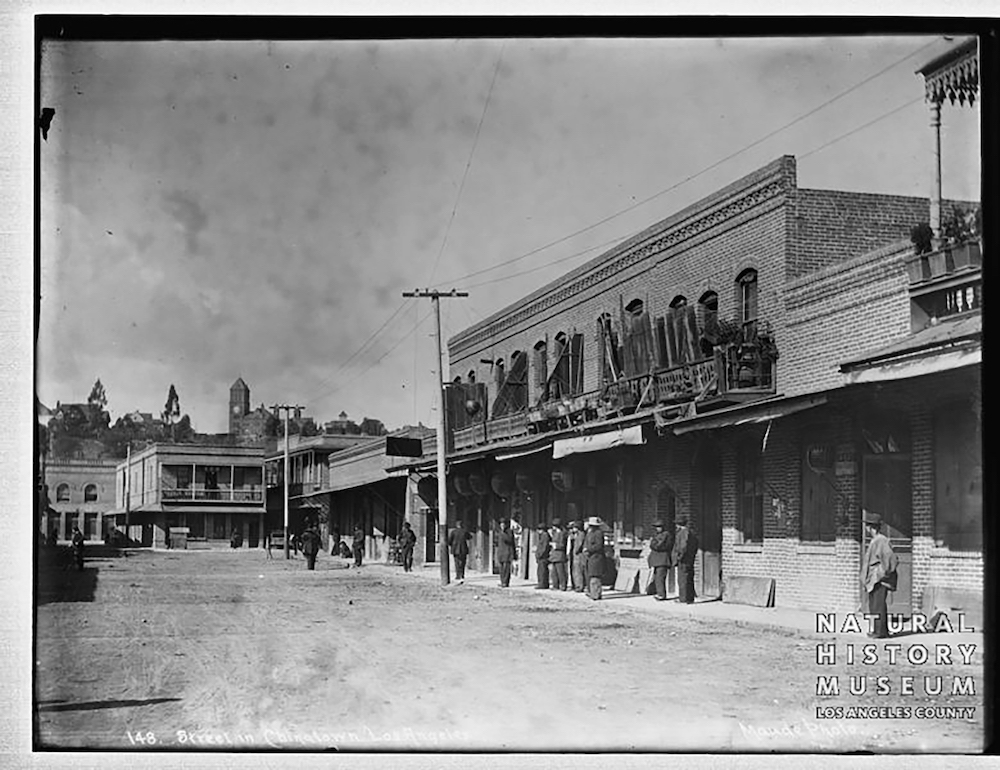

Ken Lum, United States at Night, screen print on mirror, 6’ x 6’, 2020 I asked Ken what public art commission he would like to do in Los Angeles if asked. His response was immediate. “The Chinese Massacre. Do you know about it?” I did, in fact, know a little bit because there is a plaque about it in the sidewalk in front of the Chinese American Museum on Los Angeles Street in downtown LA. What I didn’t know was that Los Angeles Street was the original location of Chinatown in what had been named ‘Negro Alley’ after the dark skinned Spaniards who first lived there. It was also the red light saloon district where Chinese had been segregated to live. The plaque is all that marks the site of what is known as one of the worst mass lynchings in US history, a part of Los Angeles’ history. It corresponded with the rise of Nativism, as anti-immigrant hostilities boiled over in 1871 when a mob of Anglo and Hispanic people attacked, robbed, and hung 17 Chinese. This history was more or less erased when Chinatown was moved to its new location in 1938. The site of the massacre is now an off ramp of the 101 Freeway. Not long after the massacre the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 was passed to maintain white “racial purity” and placate complaints that the Chinese were taking jobs. They comprised .002% of the population at the time. Why does this refrain sound all too familiar today? Over and over again Los Angeles has been an epicenter of anti-immigrant hostility, racism towards people of color, and the erasure of indigenous people. With dysfunctional immigration and homeless policies, we are in the midst of yet another chapter of a long and tortured history of abuse and neglect.

Chinese Massacre site, 1871, Los Angeles Historical Society archives In speaking with Paul Farber, who is a scholar, curator, and the Director of Monument Lab, one gets a clear sense of an organization driven by passion and forward movement. They have had numerous projects, and in particular Shaping the Past has been significant. The project facilitates a transnational exchange program bringing artists and activists together in dialogue to highlight ongoing critical memory interventions in sites and spaces in North America and Germany. It supports civic practitioners, artists, and activists who critically reimagine monuments and emerges from the ongoing Monument Lab Fellows program. These collaborations and conversations are seeking to offer innovative models for how we might memorialize the past, create dialogue, and strengthen democracy through public spaces across the globe.

https://monumentlab.com/projects/shaping-the-past

I wondered what happened after an offending monument comes down. When a statue is pulled off of its pedestal, does the question of what to put in a newly vacant town plaza become important to that site and community? Do we find meaning in leaving something behind, some kind of marker, or is it better to leave nothing at all?

Paul visited a site in Richmond, Virginia, where Gabriel Prosser, an enslaved blacksmith, was hanged after a failed rebellion in 1800. In a New Yorker article by Hua Hsu from September 15, 2020, Paul said, “When I arrived, I was deeply moved. I have visited numerous cities where empty pedestals were removed or cut off from public activity. In hindsight, it was a mistake to try to erase struggle. The deeper harms of racism were not addressed in those sites because there was no space or time to heal. In Richmond, it seemed the grassroots activists and artists changed the monument into something that reflects on the past and imagines it anew. A platform for truth, reckoning, and actual care.”

Joel Garcia has been deeply involved with indigenous issues and the removal of the Christopher Columbus statue in Los Angeles. This past April he was also part of the actions resulting in the toppling of the Father Junipero Serra statue. Joel is an artist, activist, and cultural worker whose practice intersects with the national movement to remove monuments that reflect the racist history of the United States. He is the former Co-Director of Self Help Graphics and has worked in and around Los Angeles for a long time. In 2019 he was a Fellow in Monument Lab’s Shaping the Past project.

Joel Garcia, United for Stolen Lives, 2020

On October 22, United for Stolen Lives, myself and youth from East LA helped convert the steps of City Hall in Los Angeles into an altar commemorating the 650+ lives killed by the Los Angeles Police Department and the Los Angeles County Sheriffs Department.Recently, there has been some strong push back from the Catholic Archdiocese over the numerous Serra statues that have been pulled down throughout California. This contrasts to longstanding opposition of the presence of the Serra memorials and the Mission history narrative about Serra’s benevolence towards the native population. We spoke about this and other issues related to his activist practice, monuments, and his concerns.

Clayton Campbell: Let me start with your work around the Junipero Serra statue. Serra was canonized in 2015 by Pope Francis. It seems this is consistent with Catholic teaching despite long standing opposition by native people and now a broad array of the public. The Catholic Church has said of the toppling of the Serra statues “evil has made itself present here.” Yesterday, October 20th in San Francisco, Archbishop Cordileone performed an exorcism rite at the Mission San Rafael and called the statue’s destruction “an act of blasphemy.” He also did this in Golden Gate Park in June. Archbishop Cordileone decried the “mob rule” that led to the statue of the saint being “mindlessly defaced and toppled by a small, violent mob.” He must feel the same way about what happened here in Los Angeles.

Can you tell me what is going on in LA now that the statue is down? The Los Angeles Archdiocese is the biggest in the US. Where do they stand? Can the Catholic Church be a progressive force in retelling the history of California? Is the Church moving in the opposite direction of efforts such as San Francisco’s school district to rename schools inappropriately named after Serra?

Joel Garcia: Initially, the Archdiocese was pressuring the Mayor to reinstall the toppled statue, and then it was trying to get the city to gift it to them. Rather than seek dialogue they’ve dug in and remain committed to their own narrative. Even when the Columbus Statue was in process of being removed the LA County Department of Arts & Culture had offered the statue to the Archdiocese and they initially accepted the gift but had to back out because they had recently a new set of protocols with the First Nations of Los Angeles.

“Consultation to take place with local tribal or band leaders in order to assure accuracy in the presentation of cultural and historical displays relating to Native Americans at the missions, parishes and schools within the Archdiocese of Los Angeles.”

The Archdiocese of Los Angeles has proven over and over that it can’t be trusted and because they do have a small constituency of members that are Indigenous to California, they act as if that this is an out for them. That they don’t have to be accountable; but they do.

CC: What is next with this project? Is an empty pedestal more powerful after the act of removal? Is there a time limit to the cultural memory around this? Has something else taken its place to revalue this contested site with a different story, perhaps the one the community wants to tell? Will it last; does it need to be maintained to be “alive” and understood?

JG: Until the land is returned to the First Peoples of Los Angeles, it will be a contested site. At the moment there are efforts to ensure that there is an accurate and equitable representation at El Pueblo Monument aka Placita Olvera. For the moment, that empty pedestal does resonate in a bigger way than removing it outright. As with the Columbus Statue, it is important that the city removes that in partnership with the Indigenous community of Los Angeles and dedicate resources to authentically represent what has happened here in LA.

For the time being the community, those that were there during the toppling and others have started to use that park more consistently with relation to issues concerning Native/Indigenous folks. It is good to also see that the management team of El Pueblo Monument also desires an accurate narrative of LA’s history and more equitable resources to make that possible.

So by removing the statue, it has opened up space for more constructive dialogue with the city but it needs to be consistent and it can’t always be because the community needs to topple something in order to be heard.

CC: How do you change the narrative in K-12 education about something like the Mission history in CA? Can new monuments and memorials jumpstart this process?

JG: New monuments and memorials can definitely change the way K-12 education around the Mission System is currently offered to students. Cindi Alvitre, a Tongva member and professor at CSULB just released a children’s book about one of their creation stories. Her alongside some colleagues at CSULB were also selected to offer programming through a project I designed in partnership with the LA County Department of Arts & Culture, titled “Memory and Futurity in Yaangna” where they will offer a VR experience about Puvuungna, a site of origin for many California Indigenous Peoples. In addition to that program, Mercedes Dorame, a Tongva artist will install a temporary monument at Grand Park as well. Both of these efforts are ways in which we shift that current educational model. On Indigenous Peoples Day, Cindi led a reading of her book for families and this was sponsored by Los Angeles County Library. These programs came as a direct result of the Columbus Statue being removed.

https://heydaybooks.com/waaaka/

CC: I paraphrase, but you said in a conversation with Paul Holdengraber (Executive Director of Onassis Foundation, LA), that LA is a segregated city. It seems to me that LA is indeed comprised of so many different communities with so many untold stories, often quite separate, that I wonder how do you break down these barriers, how do we move forward together? Are monuments and memorials of unification and celebration possible right now? If not, what has to happen to make them possible? What might they look like if they are?

JG: The early ‘00s had such a unique overlap of communities that came together through the music and art scene and it was a direct result of the ‘92 Uprising here in LA and the ‘94 uprising by the Zapatistas, but that dissipated because of a lack of understanding of what is widely now known by many as intersectionality. That wasn’t a framework many understood back then. That is a concept that needs to be understood by the everyday person, by my mom, my uncle, etc. But outlets like social media have offered youth such a sophisticated understanding of race, gender, class, Indigeneity, etc. that new monuments and memorials, not crafted under a European influence, can bring communities together.

At the toppling of the Serra Statue, present were members of the Black, Armenian, Puerto Rican, Chicana/o, Phillipino communities among others alongside Native/Indigenous folks. This accurate representation of history isn’t simply important to us Native/Indigenous folks but to many other communities as well, because if as a city we are willing to be dishonest about our history, what else are we willing to be dishonest about?

Joel Garcia, Toppling A Statue At Olvera, 2020

June 20th (Summer Solstice) toppling of the Serra statue at Olvera. Seconds later, youth claim the statue and the pedestal, begin covering it with flowers, fruits, and other items and reclaim the space.

Joel Garcia, Toppling A Statue At Olvera 2, 2020

Joel Garcia, Empty Site and Pedestal, 2020

September 22 (Fall Equinox) members of the Native/Indigenous community of Los Angeles repurposed the site and pedestal where the Serra statue stood and converted into a site of ceremony and reclamation using prayer flags. These same collared ribbons were also used to obscure the plaques recounting the inaccurate history of Los Angeles.

Joel Garcia, Native/Indigenous community of Los Angeles repurposed the site and pedestal, 2020

September 22 (Fall Equinox) members of the Native/Indigenous community of Los Angeles repurposed the site and pedestal where the Serra statue stood and converted into a site of ceremony and reclamation using prayer flags.CC: It seems that indigenous people, almost decimated in CA, have not had the power to keep their histories from being written by others. If money were no object, etc. what are the 2 or 3 stories (or just the one story) you would like to make as monuments in Los Angeles? And what shape might they take, what would their location be?

JG: As part of Shaping The Past a partnership between Monument Lab, the Goethe-Institut, and the Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung (German Federal Agency for Civic Education/bpb), this is a conversation we had on Indigenous Peoples Day (to be broadcasted soon) with Cindi Alvitre and Guadalupe Rosales of Veteranas & Rucas, and I feel I am not the best person to offer such suggestions as California is not my ancestral homeland, but I can share what Cindi offered up, and she and others would like to see their ways of memorializing their ancestors with “Ancestor Poles” be visible within the city. Maybe a field with a hundred ancestor poles. In order to reconcile with our past here, we have to make space to honor what we destroyed in order to have this city. Some possible sites could be Olvera, the California State Park along Alameda, Grand Park, for example.

https://www.instagram.com/veteranas_and_rucas/

CC: Monument Lab is planning future work on the West Coast with its audit of monuments, maybe setting up field offices on the West Coast, and an exhibition of the Shaping the Past project you are a 2019 Fellow in. Can you give me a preview of this exhibition for Artillery’s readers?

JG: Part of this work has begun already as on the Fall Equinox we took over the site where the Serra Statue was and converted it. We changed the aesthetic of the place by simply using ribbons as you saw during the interview with Paul for Counter Memories. Because of COVID safety guidelines, we’ll be doing most of this work outdoors changing the way some of these places feel and look like to infuse them with ways of memorialization by Indigenous folks. For example, on November 2nd in East Los Angeles, we will be installing altars at 15+ sites where our community members were killed by the Sheriffs, and that’s just in the last 4 years, just in the East LA area.

But this work will also come in the form of the DIY culture prevalent in the Punk scene I grew up with, with some zines on how to do this work alongside the community.

CC: What work are you doing now and in the next year or two around the themes of monuments in the context of your overall practice as an activist and artist?

JG: Much of the work that exists at the moment around monuments is not sexy at all, it is mostly about shifting existing policies and funding streams to create truly equitable opportunities for marginalized and targeted communities to be represented, specifically the First Peoples of this city. I approach this work as an artist, as a hacker, finding loopholes to do things now and identifying current restrictions that need to change to be better reflect where we are now as a society.

And as an activist, I have to also keep a pulse on what the moment is feeling like. The Serra Statue was something many folks for decades attempted to remove but it was also recognizing the “Go” moment at the time to just get it done. But not recklessly either as it was meticulously planned, recognizing the legalistic realities of a toppling, and ensuring people’s safety as we had families present.

As an artist, you create big moments to uplift underrepresented voices and similar to the 2018 Banner Drop at the World Series in support of the Trans Community, we would probably be doing something just as big again during this World Series, so keep an eye out.

https://www.teenvogue.com/story/world-series-trans-pride-banner-drop-translatina-coalition

At this writing, we are in the aftermath of a contested Presidential election. The challenges ahead do not suggest collective acceptance of cultural narratives that can be easily agreed upon. How artists and creators like Joel Garcia, Ken Lum, and Paul Farber (along with their socially engaged colleagues who collaborate with new organizations like Monument Lab) go forward from here may tell us a lot in the next few years about our social and political destiny. It seems the necessity to speak truth to power by our artists and creative organizations is more important than ever before. Can artists contribute to activating a transcendent, collective healing and reconciliation? Will their memorials and monuments, whatever shape they take, be reminders of when we as a country authentically embraced a willingness to listen to each other without judgment? Is that our mandate, what must be accomplished, if our new and yet unrealized monuments are to endow future generations with wisdom, celebration, and truth?

Joel Garcia, Translatinal Coalition Banner Drop, 2018

On October 28, 2018, the Joel and the TransLatin@ Coalition, a Los Angeles-based nonprofit that advocates for the specific needs of the TransLatin@ community in the U.S., unfurled a large banner reading “Trans People Deserve to Live” over the upper deck of left field during the game’s fifth inning. -

Mark Spencer

Currently on display at the Center of Contemporary Art in Santa Fe is the 30-year survey of Mark Spencer’s paintings. Entitled “Beings,” this is a rare and all too brief opportunity to experience an important artist.

Mark Spencer, Blue Streak, 2019 Some artists’ practice is to work slowly and deliberately. The measure of their oeuvre manifests over the full arc of a career when their work can be gathered and viewed as a whole. This is the case with Mark Spencer who has been working in Santa Fe, away from New York, Los Angeles, Europe, the art fairs and major galleries. But I feel that “Beings,” (which didn’t include his significant output of pencil drawings and monotypes) would successfully hold forth in an institution like UCLA’s Hammer Museum. I can think of several Los Angeles curators who would do justice to an exhibition of Spencer’s full body of work. In my opinion, a full retrospective exhibition would be equal to that of artists like Lari Pittman, Llyn Foulkes or Vija Celmins, who were presented so well at the Hammer. It is time Spencer was seen by the Los Angeles arts community and recognized by a major national institution.

Mark Spencer, Pygmalion, 2016 Spencer’s work takes on a great spiritual conundrum of our era, which he describes as the inherent conflict of Nature vs Human Nature and how it has become a threat to the planet and a block to the evolution of the species. His deep philosophical engagement with this question is accomplished through an examination of his unconscious processes, beginning with abstract sketches that evolve into highly polished oil paintings. The total output is a metaphorical representation of the world we live in and pass down to future generations.

Mark Spencer, Vernal Equinox, 2014 His oil paintings and monotype printing are currently some of the more remarkable hybrid representational-expressionistic productions I am aware of. 1984’s Heart of Darkness (72 x 58”) presages overarching concerns that will underline future allegorical works. Two central figures are wrapped in a cornucopia of tangled materials, capped by a wolf-like animal killing a white bird, anchoring the dramatic misc en scene. This metaphor of bound and confined is repeated throughout his imagery. Dangling from the hand of one of the figures is The New York Times, revealing the news of the day. The headlines announce, “Nuclear buildup threatens world peace; El Salvador at odds with death squads; South Africa in revolt; and Israeli jets bomb Palestinian’s in Lebanon.” Mixed in with these weighty world conflicts are more domestic bylines with an overtone of black humor, “Jealous husband has shootout with wife’s lover, 2 die; Giant carp kills 15; and, Spencer’s Heart of Darkness causes art-world stir.” There is something in the work that traverses the ridiculous and the sublime, giving us just enough air to breathe while looking at Spencer’s paintings, boiling over with psychodramas.

Mark Spencer, Beings, 2018 Twenty-five years later Spencer would make Beings (2018, 60 x 108”). He describes arriving at this work by “I gain awareness of what part of the conflict between Nature and human nature that I’m dealing with. The image then begins to evolve and take on a life of its own. It becomes a being.”

This articulation in oil paint lays the central conflict in his work at the feet of the male ego, driven to dominate nature through greed and power lust, to which both men and women can succumb. Pictorially the work is animated by what appears to be a struggle to find balance. The resulting art, Spencer says, is a “hybrid reality, a bridge between the world of personal experience and the collective spiritual dream.” A series of paintings in the exhibition, like Vernal Equinox (2014, 74 x 96”), Chaos (2016, 24 x 36”), Pygmalion (2016, 52 x 80”), or Blue Streak (2019 72 x 108”) exemplify this statement. The irony, of course, is that this exhibition is shuttered at CCA by the coronavirus pandemic, at the precise moment in time when Spencer’s overarching project is so profoundly in focus.

-

Kate Johnson, 1969–2020

This past March Los Angeles lost a truly wonderful artist, Kate Johnson, after her courageous three-year battle with cancer. She undertook this journey with dignity that I hope I have if I ever need it. I have known Kate since 2000 when she and Michael Masucci brought their organization EZTV to be in residence at the 18th Street Arts Center. Kate was truly generous, kind and giving, one who understood the meaning of community. An outstanding artist and cultural producer who had fully hit her stride when diagnosed, Kate nevertheless continued to make work and teach at Otis College, inspiring those around her with her will to live and interest in life.

Kate Johnson, JuneMoon video still, 2005 Kate’s practice was hybrid, working in forms often presented outside conventional platforms. She exhibited large-scale projections and videos and critically acclaimed works in a variety of media and genres, exploring the nexus and connections between art, anthropology, technology and social justice. She is at the forefront of women working in large-scale site-specific digital projection, creating massive original projections that locally graced iconic places such as the Getty Center, LA City Hall, West Hollywood Park and Japan American Cultural Center. With the mind and talent of an artist/scientist/engineer, Kate wrote the film scripts and computer code for many of her projects including directing, shooting, animating, editing, coding—producing video artworks often accompanied with original music and sound-design compositions.

Kate Johnson, Projections at Getty, Pacific Standard Time, 2011 Her collaborative work informed much of who she was and became. In 2015 she received an LA Emmy for co-producing and directing with Maria Ramas the film Mia, A Dancer’s Life. Kate emphasized the importance of her 20-year collaboration with artist Barbara T. Smith, as well as projects with artists Susanna Bixby Dakin, Loretta Livingston, S. Pearl Sharp, Mythili Prakash and Aditya Prakash as significant to her development as an artist and a person. Works for which Johnson was a principal collaborator have been presented at several national arts institutions including MoMA (NY), Cannes Film Festival, Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts, Institute of Contemporary Art (London), locally at UCLA, USC, Highways, Los Angeles Theater Center, the Japanese American Cultural Center, including several LA galleries—and of course, her creative home: EZTV.

Kate Johnson, Aboreal Witness, Descano Gardens, 2018 The last time I saw Kate she was going into her studio at EZTV, not so long ago. We spoke for a bit; I asked her how she felt. She expressed hope, but said things had taken a turn and didn’t elaborate. I found a few things to say that were hopeful—her face brightened a bit—and her great smile flickered. She was beautiful, radiant, her soul close to the surface. I really don’t know how else to express this, but it is how I will remember her. She was my friend.

Kate Johnson, “Everywhere In Between”, Bergamot Station, 2015 To view Kate Johnson’s work, go to: https://www.katejohnsonartandfilm.com/gallery

-

Studio Visit with Lisa Diane Wedgeworth

Lisa Diane Wedgeworth is one of LA’s talented mid-career artists whose work steadily and forcefully moves to the foreground of our consciousness with its thoughtful and compassionate investigations of her emotional life. Her striking paintings, self-referential videos and narrative documentary projects of intergenerational relationships have garnered her a 2020 C.O.L.A. Individual Artist Fellowship, and artist residencies at The Hermitage, and the prestigious Georgia Fee Residency in Paris. I’ve known Lisa since 2000, and we recently met in her studio.

CC: The growth of your work into a range of media—painting, photography, mixed media, video, writing, performance—seems to capture the breadth of your practice. Let me begin by asking you to give me your artist statement in 35 words or less. You’re on!

LDW: I unapologetically investigate memories, relationships and immediate experiences as spiritual and psychological energies that take form as paintings, video, performance, archived personal narratives and any medium deemed necessary.

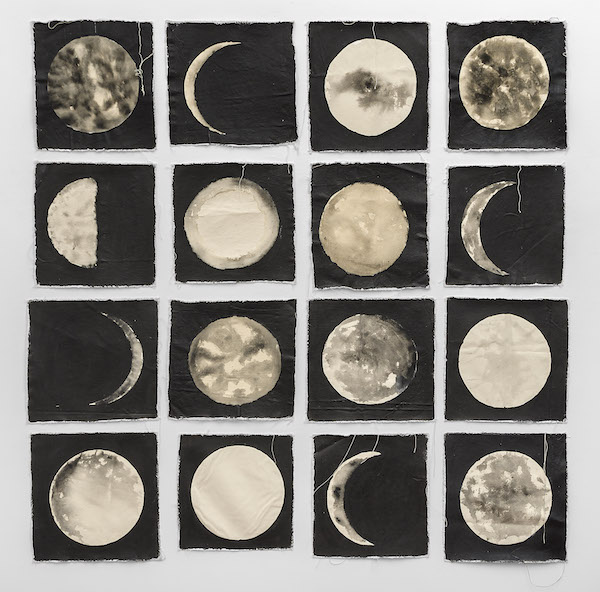

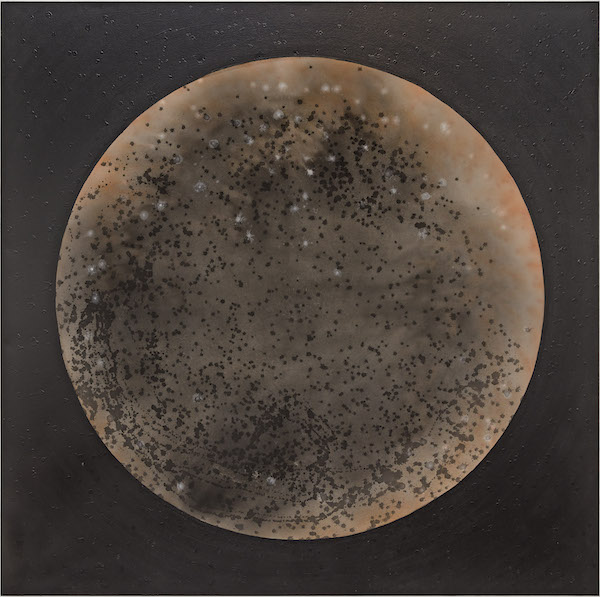

Lisa Diane Wedgeworth, Brown But Beautiful, 2014 I was taken by your 2014 exhibition of paintings of celestial bodies. In our conversation you revealed that each celestial painting related to a particular event in time and space, such as Katrina, or a traumatic event in the African-American community. Can you tell me more about how these experiences are embedded in the work?

These events were all traumatic to the African-American community. If one is abused, injured or hurt, we all are, even the person or group of people causing the trauma… we all inherit the energy in some emotional or psychological way. The paintings were informed by historical and personal experiences such as the 1963 bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church, Loving vs. Virginia, the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina and two familial experiences relating to my maternal grandmother’s abusive relationship towards my younger sister.

Lisa Diane Wedgeworth, Sex Lies & Brooklyn Spies, 2015 When I began these paintings I was thinking about the matrilineal intergenerational relationships within my family. My sister was experiencing a psychotic episode that focused her delusions on me (falsely) being an evil spirit capable of harming her and her son, I was reading Foucault’s Madness and Civilization and was researching the relationship between the moon and its effects on human psychology. Maybe on some level I was trying to make sense of the horrific ways in which humans relate to each other—are we really doing these things to each other willfully or is there something greater than ourselves influencing or dictating how we engage?

So, these paintings became this exploration into relationships. If the celestial bodies existed first, were they influencing human behavior on earth? I’d prefer to think of the bodies as evidence. I don’t want to entertain the idea of making excuses for the pain and trauma historically or currently being inflicted on anyone.

Lisa Diane Wedgeworth, Sane Sister, Schizo Sister, 2015 In 2015, these celestial works connected with the earthly in your new paintings and video, in which you narrate personal experiences from your childhood. By 2018, you were working with self-portraits. What is the trajectory you have followed in those years?

I don’t know if I am following, yet I am definitely being led along a path and I’d like to think that when I’m still making work at 80 or 90 years old I can answer that question more clearly. I knew in grad school that I wanted and needed to be honest and authentic in my work—that was and is important to me. The work has moved from making paintings that were informed mostly by historical events and observations about others to my own experiences.

Lisa Diane Wedgeworth, Mrs Johnson and Mrs James, 2015 By the time this prints, I will have celebrated my 50th birthday. I am a different woman than I was at 25 when I gave birth to my daughter. I move differently, my love life is very different, my needs and desires are different; I have new responsibilities and priorities. And, I am only 80% at peace with aging (laughs). So, I have a lot to unpack in my own life and these concerns, obligations and revelations are manifesting in my work.

I would say the trajectory is truth. It’s unapologetically moving with the changing truths in my life. I was afraid of math as a child and geometry terrified me. Today, geometric shapes mean so much more to me. I’m fascinated by the relationship I see between their multitude of angles and sides and my ever-changing roles as a woman who is now 50. I am really excited about what these new works mean and look like.

-

Sarah Lucas

“Well-behaved women seldom make history,” asserted historian, Harvard professor, and Pulitzer Prize winner Laurel Thatcher Ulrich in the 1970s about why women who act in unexpected ways are often remembered, while more conventional women fade into the background. Sarah Lucas is one misbehaving woman if there ever was one. Unashamed and unapologetic, her retrospective exhibition at the Hammer Museum reveals a mid-career artist in full force.

Lucas injects a female sensibility in her references to contemporary art history. Throughout each evolution of her work, from the early 1990s YBA pieces to her most current efforts, she creates new visual strategies that break with conventional behavior. Lucas is a feminist who has never looked back. Given millenniums of patriarchal dominance, the issue of women speaking out is necessarily that of their speaking out of turn. And speak out she does, at every junction in her work, with tremendous humor, British working-class grit, honesty and terrific craft.

Sarah Lucas, Edith, 1994, ©Sarah Lucas, courtesy Sadie Coles HQ, London There are numerous works that stand out, beginning with the signature piece Au Naturel. Composed of a soiled mattress, two melons, tomatoes, a cucumber, and a bucket, the remnants of a night of gritty coupling has never been so economically portrayed. The title of her first show, Penis Nailed To A Board, was a sign of the “what the fuck is this?” reaction she can still generate. Her self-portraits from Eating a Banana (1990) to the Red Sky Blue (2018) serve as larger social critiques as well as deeply personal statements. In considering the genre of artist self-portraits, hers are a major revelation. They are as revealing as those done by any artist in recent memory and create a wonderful, eclectic body of work.

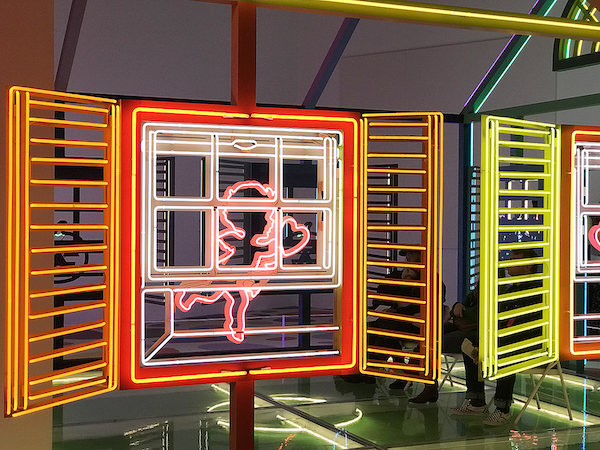

Lucas has filled the Hammer’s galleries with sculptural projects like Bunny Gets Snookered: stockings stuffed into humanoid forms, thrown over chairs, legs spread wide, vulnerable and violated with everything showing. Adjacent galleries are installed with plaster and wire variations of erect cocks and balls. Throughout the galleries male genitalia are ubiquitous, decorating wallpaper, floating in pictures of soup. Lucas gleefully transforms cocks into a common fetish object in much the way that women with unreal, giant breasts are dehumanized in her British tabloid canvases like Seven-Up from the 1990s. Everyone gets equal time as Lucas’ work upends notions of gender and sexuality.

There are over 130 works in all: the life-size Crucifix covered in cigarettes, the Muse torsos and numerous videos; in total, a body of work with multiple art references that reach far deeper than surface brio. Lucas’ retrospective has been linked to the #metoo and environmental movements, but I feel this would miss the point that she has always been her own person and a singular artist. If her work syncs up with social and political agendas, it is serendipitous. She has been misbehaving from day one.

-

TONY CONRAD

“Introducing Tony Conrad: A Retrospective” is the first large-scale museum survey devoted to work originally presented by the artist in his museum and gallery exhibitions. It premiered at the Albright-Knox Art Gallery and has traveled to the Institute of Contemporary Art at the University of Pennsylvania where it is on view through August 11. It is a terrific send off for an under-recognized artist.

Conrad, who died in 2016 at the age of 76, is one of those uncommonly delightful figures of the second half of the 20th century who privileged disruption over mastery. His instinct was to eschew the pressures to adhere to a specificity of discipline and really lean into interdisciplinary crossovers that now seem ubiquitous. He opened creative possibilities between art and film, film and music, music and performance in contemporary practice that were quickly picked up and acted upon by other artists. He often was the one who got there first. Innovators are not always the ones who reap the rewards, nor do they necessarily want to. Perhaps this is why Conrad is not well known and this exhibition is a revelation.

Anti-gallerist and anti-commerce for much of his career, he taught for a living at the University of Buffalo. He made art that would not, or he would not, sell. An artist’s artist, some knew of him, were influenced and worked with him, like Mike Kelley, Tony Oursler, Cory Arcangel and Constance DeJong. Yet even Conrad said of himself, “You don’t know who I am, but somehow, indirectly, you’ve been affected by things I did. I don’t mind being anonymous though.”As a young man Conrad was already immersed in art and avant-garde music while he studied mathematics at Harvard University. By 1962 he began playing violin with the Theatre of Eternal Music, a pioneering drone-based minimalism project with John Cale, La Monte Young, Marian Zazeela, Angus MacLise and others. For a brief moment he was part of The Primitives, a proto-Velvet Underground band with Lou Reed, Cale, and Walter De Maria. Conrad was also roommates with the pioneer filmmaker and performance artist Jack Smith, and made music for some of Smith’s films.

When he was given film stock from Jonas Mekas, Director of the Anthology Film Archives, Conrad began making groundbreaking films of his own. The first major work that stands out from this propitious moment is The Flicker (1966), an underground work, which literally flickers like a strobe light. It is about the very act of projection itself. The movie is accompanied by a warning that it may cause seizures, and numerous persons have left screenings with headaches and feeling ill.

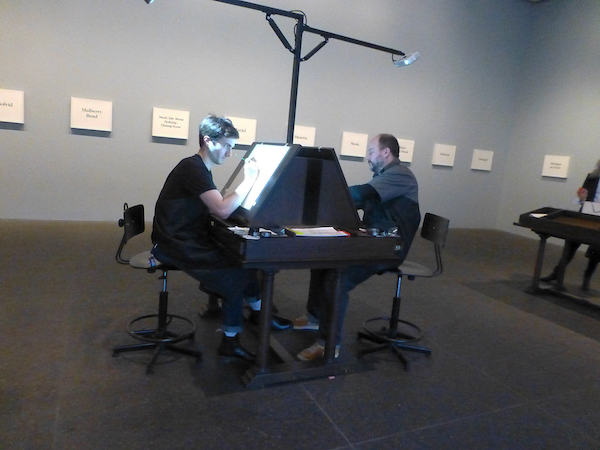

Tony Conrad, Retrospective, installation view (2019) courtesy The Institute of Contemporary Art at the University of Pennsylvania. The exhibition covers an enormous amount of ground and numerous works stand out that evidence Conrad’s restless spirit and sensibility of consistently challenging systems and boundaries. In particular his Yellow Movies (1972-73) are unique, seemingly endless durational works that employ no film or projectors. Elsewhere there are drone instruments he invented that investigate the confluence of harmonics, music and sound. Then in 2016, as perhaps an unintentional parting gesture from someone who seemed to impart a degree of humor in everything he did, there is a hilarious installation of oversized underwear entitled Undone. It bemoans aging and the ridiculous indignity of it all as the body sags and loses its functionality.

Some of his video projects, like the Homework Helpline on Buffalo Learning Television from 1993–97, are especially affecting and unexpected because of their earnestness and kindness. Conrad is just great with kids.

Several movies featured Kelley and Oursler. They were Hail the Fallen (1981) and Beholden to Victory (1983), both war movies, and a B movie genre “women- in- prison” film, Jail Jail (1982–83). In these you see the young artists performing in what seem to be improvisational styles, seemingly without direction. Jail Jail’s set is recreated in the exhibition. It was scheduled to be continued 30 years after its initial shoot, by bringing the actors back, but was cancelled after Mike Kelley’s death.

If Conrad was a free spirit and a restless mind, then he was also The Joker in the midst of an art world that became unrecognizable and market-driven with a cruel speed that almost left him behind. This wonderful exhibition more than makes up for it, and it is a shame he isn’t here to upend it somehow, because given his nature I am guessing that is what he may have planned to do.

-

Museum Joy

The last time I was bowled over by an artist’s installation was Damien Hirst’s Theories, Models, Methods, Approaches, Assumptions, Results and Findings at Gagosian, New York in 2000. I have just seen and felt the bar raised again. The artist doesn’t live in New York or London, but in Philadelphia. And the artist is not showing in an upscale art fair in Los Angeles, but in Pittsburgh. Alex Da Corte’s Rubber Pencil Devil installation is an epiphany. It is a wonderful manifestation of curator Ingrid Schaffner’s refreshingly idiosyncratic theme or intention for her 57th installment of the Carnegie International, ‘museum joy.’ Schaffer says, “The aim of this International is simply to inspire museum joy. Simply put: the pleasure of museums comes from the commotion of being with art and other people actively engaged in the creative work of interpretation. Draw on what you know.”

Running from October 15, 2018 through March 25, 2019, the Carnegie International is the second oldest international contemporary arts exhibition. The initial impulse of having this survey was to advance international understanding with a bilateral process of North American and European curators working and consulting together. To curate and select artists, Schaffner worked with “companions” Magalí Arriola (independent curator, Mexico City), Doryun Chong (Chief Curator, M+, Hong Kong), Ruba Katrib (Curator, MoMA PS1, New York), Carin Kuoni (Director, Vera List Center for Art and Politics, The New School, New York), and Bisi Silva (Founder and Artistic Director, The Centre for Contemporary Art, Lagos, and sadly, passed away on February 12th of this year at the age of 57) who added to Schaffner’s international research by each traveling with her to destinations new to them. This was the bilateral process desired by Carnegie and carried out by Schaffner in a unique way. Presenting work by 32 artists and artist collectives, the exhibition invites visitors to explore what it means to be “international” at this moment in time, and to experience museum joy in doing so.

To navigate Schaffner’s final concept, there is a smart, scholarly, pleasure-to- read Guide. It is accessible, friendly, doesn’t talk down and also takes the place of absent didactic wall labels. It was refreshing wandering the Carnegie Museum, not being told what to think, or reflexively reading the label first and looking second. Instead there was the joy of following the loosely laid out trail, making discoveries, finding connections, taking breaks, reflecting, reengaging, all without the usual props and instructions. There were guides in each gallery, elaborating on the work. And if needed, kiosks in the museum where friendly people (true, they were friendly) would answer any questions you asked about the show.

Walking up to the museum there is an auspicious beginning. El Anatsui’s monumental installation, Three Angles, made of folded off set printing plates meshed together with one of his signature bottle cap tapestries traverses the entire exterior façade of the museum entrance. It is an out of the box effort by this major artist who doesn’t hold back. We are used to seeing his brand, and he breaks the mold for this commission.