Your cart is currently empty!

BUNKER VISION The Prime-Time Underground Film

The history of film is full of paradigm shifts. Once people got used to the idea that the train on the screen wasn’t going to burst into the theater, they had to adjust to editing. When a character had a memory, the idea of linear time was disrupted. One of the biggest shifts arrived with the debut of MTV in 1981. Until it arrived, the most likely way one would have seen those rapid edits would have been in a film history class that was studying Russian cinema, or such underground works as Kenneth Anger’s Scorpio Rising (1963–73). This might help one to understand how shocking a TV show called Turn-On was to the uninitiated viewer in 1969. A year earlier, a television show called Rowan & Martin’s Laugh-In (1968) featured rapidly edited blackout comedy sketches. But these were offered in the context of a show that had tuxedo-clad hosts and Hollywood production values.

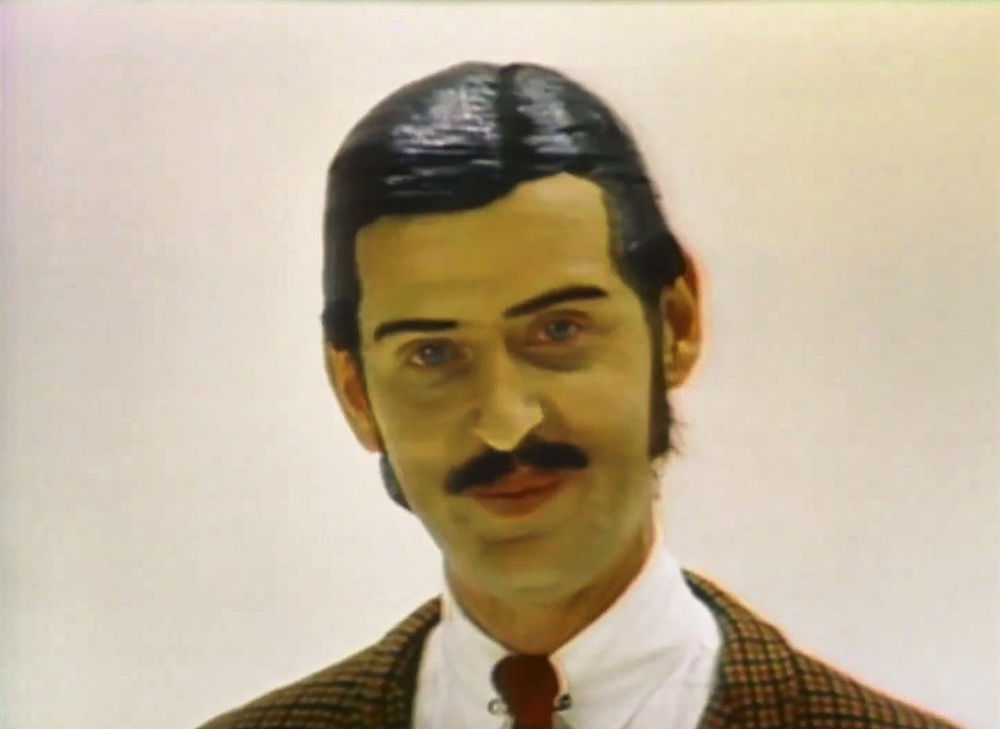

By contrast, Turn-On billed itself as the world’s first computerized show. This premise allowed them to dispense with sets, as the skits would appear with a white background with Moog synthesizer sounds instead of a laugh track. The show was shot on film (unusual for the time) and the screen would sometimes divide into four images. Animation, videotape, stop-action film, electronic distortion and computer graphics were employed for what was intended as an audio-visual assault. Going with the mistaken idea that Laugh-In had broken more ground than it had with censorship and fast-paced editing, the creators of Turn-On sought to push the boundaries even further. The edits became faster, more random, and were used to sneak in things that might get past the censors. In this pre-VCR era, such things were quite literally a blink, and you missed it. You couldn’t stop the picture or rewind what you had just seen.

Within minutes of the show starting to air its premiere episode on the East Coast, the switchboards were lit up at every station that aired it. Viewers weren’t just upset by the content; they were experiencing a form of sensory overload that nothing had prepared them for. Households where more than one set of eyes were on the screen were catching those hidden bits in the montages. Stations started pulling the show off the air during the first commercial break, and some stations further west were refusing to air it altogether. Despite having a second episode in the can, the show was canceled and thought lost. Recently, both episodes turned up on YouTube. It hasn’t aged especially well, but it’s wonderful to remember a world in which millions of primetime viewers got to see an underground film