“And so it was I ate my pet [a rabbit] and remembered all of the fun times of summer. [. . .] That was the season when I realized that I must leave my loves behind.”

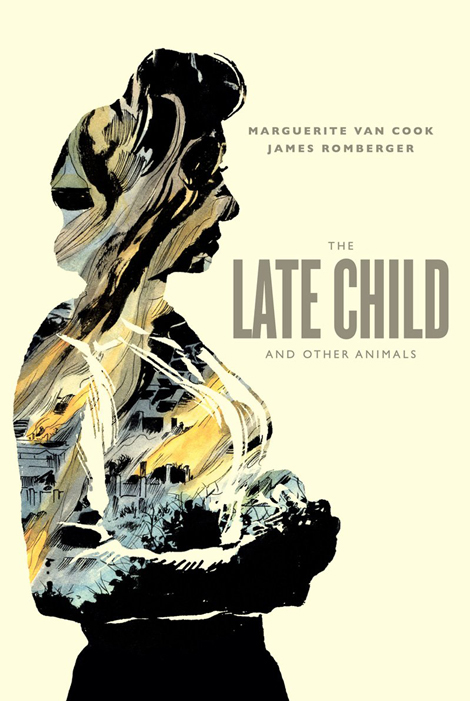

Coming of age on the Norman coast and in the streets of Paris in the shadow of 1968: this delirious narrative with its sibilant echoes of the French nouvelle vague forms the climax of Marguerite Van Cook and James Romberger’s wonderful new graphic novel, The Late Child and Other Animals.

Based on Van Cook’s childhood recollections as well as the story of her mother struggling to survive the Blitz and life as an unwed mother in dreary postwar England, the novel can be as terrifying as the darkest night and as gloriously bright as a garden bursting with brilliantly sunlit flowers. Although it plumbs the depths of depravity and despair, it ends on a note of affirmation, strength and independence. Little Marguerite may have been late into the world, more burden than gift; but the teenaged Marguerite, her lithe tan body knifing into the cold water of the Channel for a final late summer swim, is clearly working to her own timetable. Her body moves with supple grace, and her closed eyes suggest an unencumbered interior self no longer horrified that a pet rabbit might make a tasty ragout.

In their work with David Wojnarowicz on the coruscating 7 Miles a Second (1996; reissue: Fantagraphics, 2013) Romberger and Van Cook developed a brilliant graphic style perfectly suited to the violent intensity and hallucinatory vision of their author’s prose. That apocalyptic picture is moderated in The Late Child, matching the tone of Van Cook’s memoir. Still, both the line art and the color retain a compelling intensity that drives and modulates the narrative. Seen from inside, both the life of a solitary child and that of an unwed mother fighting her own shame and the relentless moralizing of an anonymous and unsympathetic bureaucracy can be intensely vivid, a series of vertiginous ups and downs interspersed with agonies of boredom or suffocating anxiety. Working from Van Cook’s spare but enormously resonant prose, the artists have captured all this perfectly, with a virtually cinematic power to draw one into the book’s world, to surround and submerge a reader in situations of compelling immediacy.

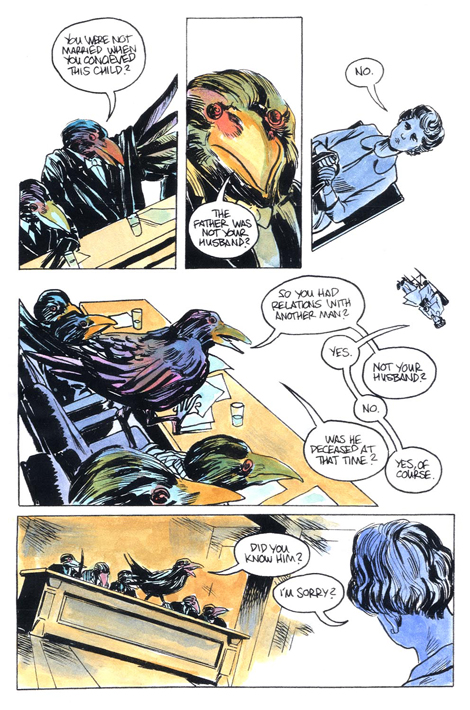

The sequence in which Marguerite’s mother Hetty confronts a transmogrified social welfare committee—half a dozen censorious men whose specific identity restlessly shifts from human to crow to hybrid—is a truly terrifying vision. Poor Hetty is trapped in a space that manages to be at once vast and claustrophobic, suffocating in an atmosphere compounded of sweat, shame, prurient sexuality, religious hypocrisy and sham moral indignation. All of which we breathe in with her.

Likewise the rising crescendo of terror that provides the arc of the story “Nature Lessons.” There, the innocent risk-taking of youth, and the internal tension between tomboy and ballerina are mercilessly perverted as the young Marguerite becomes prey for a wily pedophile; and only the fact that “I was faster than the boys and I could run” saves the reluctant dancer from murder and rape. Again, it is not just the plot, but the power of the prose and line work that pull no punches, and the expressionistic yet balanced color that makes the book impossible to close, even as the rescued Marguerite imagines herself “finally free of the soot of the modern world” as she sinks into the Victorian aquatic paradise of Charles Kingsley’s amazing 1863 fantasy, The Water Babies.

It is, however, the natural as well as the urban world that holds lessons for Marguerite, as we see in the beautifully told and visualized “Arreton Downs.” Not only does this lyrical tale dissect the entire English “magic garden” tradition, it manages to make perfectly clear just how fine is the line that separates the magical from the malevolent, the sweetness of the berry from the sharpness of the thorn, the innocent explorations of the child from the back-breaking labor of Millet’s Gleaners.

In all, this is a quite extraordinary piece of work. It sweeps us flawlessly along from a hillside above Portsmouth burning in the Blitz to a Parisian café terrace at the end of the turbulent ’60s. Wonderfully conceived and skillfully executed, it holds its own both as literary and as graphic art. And for all its evident terrors, in the end it provides a simple and irrefutable affirmation of one girl’s ability to achieve freedom and equilibrium in a complex and quite ambivalent world.

Marguerite Van Cook and James Romberger,

The Late Child and Other Animals

Seattle: Fantagraphics Books, Inc., 2014 | 174 pp. hardcover