The only quibble I might have with the Getty’s excellent show, “Light, Paper, Process: Reinventing Photography,” would be that its title is too literal-minded. A show as exciting as this one is might have had a more adventurous title – say, “Back to the Future,” or maybe “The Framebreakers.” On the other hand, the show’s curator, Virginia Heckert, might counter that the material in her exhibition is so full of paradoxes you don’t need to add another layer with a quippy title.

My analogy to the 19th-century Luddites in England, who were hand weavers that rebelled against the industrialization of their craft by smashing the mechanical weaving frames newly invented then, occurred to me because digital technology is causing a comparable upheaval in the history of photography today. But the reaction of the seven photographers in the Getty show to the situation now is more complicated – more witty and contrarian. For what these artists are breaking down and breaking up is not the new invention, but the old ways in which photography has been done since the 19th century.

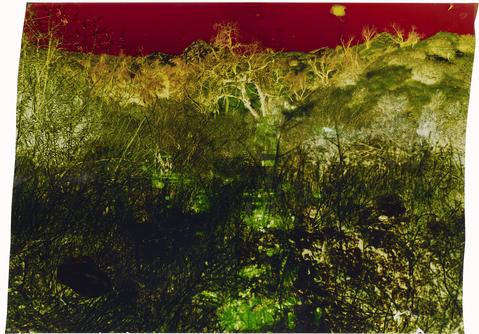

John Chiara, American, born 1971, Sierra at Edison, 2012, Chromogenic photograph on Kodak Professional Endura Metallic paper (50 x 72 in.)

John Chiara, Starr King: 30th: Coral, 2013, Dye destruction photograph on Ilfochrome paper

(33 x 28 in.)

Consider, for example, the work of John Chiara. Californians will recognize in his landscape photographs a nod to the mammoth-plate camera used by fellow San Franciscan Carleton Watkins to make some of the first photographs of Yosemite in 1861. Chiara’s “Big Camera” is gigundous; it’s a room-sized contraption he trailers to the sites he photographs and in which he can make images as big as 50 x 80 inches. He also goes back to the very earliest experiments in which photographers tried to make direct positives, before the advantage of the negative was discovered. Chiara’s are made on glossy color stock that he processes by sealing it, along with his chemistry, inside a six-foot length of PVC pipe. He sloshes the print around in the chemicals by rolling the pipe back and forth on the floor. The result is a print beguiling in its crudeness, its in-and-out-of focus beauty and irregularly cut edges patched together with Scotch tape.

A comparably primitive homage to photography’s past is apparent in all the work in the exhibition. Photographs made now in the vacuum of cyber space and processed in the sterile nether world of the computer have driven industrial giants like Eastman Kodak out of business. It was a civilization, as lost now as that of the ancient Incas, to which Allison Rossiter pays a kind of archeological tribute by finding and processing photographic papers long expired. In the digital darkroom, nothing needs to be left to chance, whereas in her work, everything is.

Her first experiment was with a box of Kodabromide E3 that had a 1946 expiration date. She took a sheet of that paper straight to the darkroom and processed it, as she would all her finds, without having exposed it in a camera. Processed, that first sheet looked, as she put it, “like a rubbing on a gravestone.” Sometimes her surprising results are “found photograms” (i.e.,cameraless images made by putting a physical object on photographic print paper and exposing it to light). Her photograms were created by “light leaks, oxicidation, and physical damage” or were “etched into the emulsion surface by mold.”

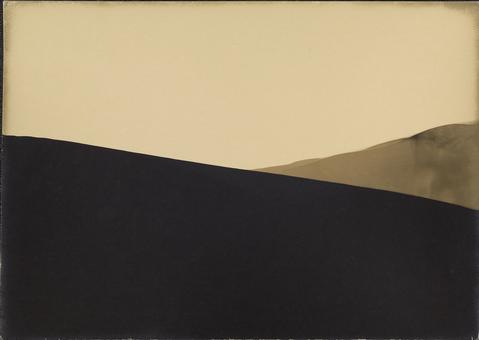

Alison Rossiter, American, born 1953, Kilbourn Acme Kruxo, exact expiration date unknown, about 1940s, processed 2013, Gelatin silver print

At other times she purposely evokes classic modernist compositions like, in her Kilbourn Acme Kruxo piece, Edward Weston landscapes from the 1930s. Because expiration dates “provide reference points on a time line through world history,” she also processes in a way that will evoke the paper’s era. Thus does a sheet expired in 1910 come out looking like a Word War I bomb exploding above a field of mud. Photographs from 100 years ago are usually prized for their ability to show us literally what happened then. The paradox inherent in Rossiter’s process is that it enables photography to work in metaphorical and symbolic ways.

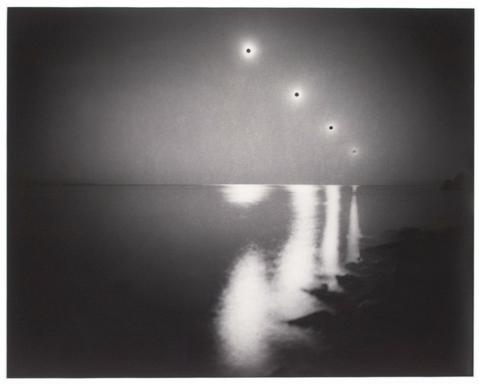

Lisa Oppenheim, A Handley Page Halifax of No. 4 Group flies over the suburbs of Caen, France, during a major daylight raid to assist the Normandy land battle. 467 aircraft took part in the attack, which was originally intended to have bombed German strongpoints north of, 2012

The other woman in the exhibition, Lisa Oppenheim, goes back even further into the history, though in a more specific way. Two of her three projects on view recreate actual 19th-century photographs of the sun (from uncredited glass positives dated 1876 at the National Museum of American History) or the moon (from exposures New York University professor of astronomy John William Draper made in 1850 – 51). Resorting to today’s digital technology, Oppenheim scanned the original positives to make enlarged copy negatives with which she could create her own “Heliograms” and “Lunagrams,” using the light of the sun or the moon for her exposures. The Lunagrams, made during the same phases of the moon that Draper had recorded, are the most seductive works in the exhibition because Oppenheim used a silver toner to replace the highlights in the black-and-white prints with a rich metallic caste as cold and beautiful as moonlight itself on a crystal clear night. Oppenheim’s third series, of smoke billowing from a World War II bombing raid, was printed in the light of an open flame because incendiary fires below were what illuminated the clouds in the original prints.

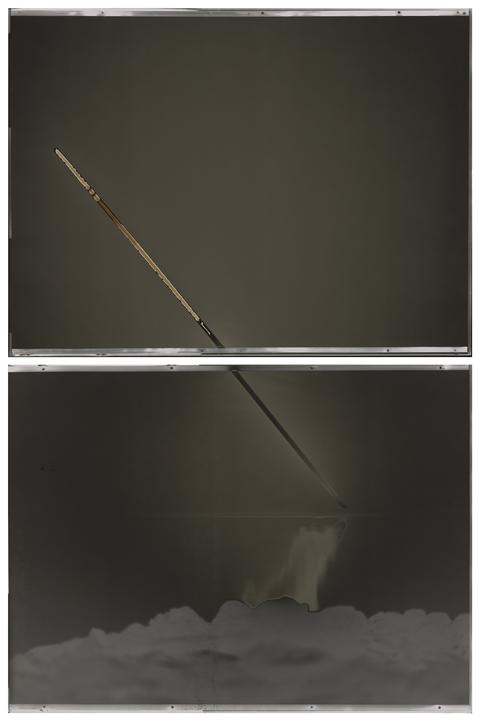

Chris McCaw, Sunburned GSP #609 (San Francisco Bay), 2012, Gelatin silver paper negatives (30 x 40 in.)

Chris McCaw, American, born 1971, Sunburned GSP #202 (San Francisco Bay), 2008, Gelatin silver print

The women are the more creative artists in the show. The men are the more destructive – or, anyway, deconstructionist – ones. Chris McCaw discovered the technique he uses by accident. Camping out in order to photograph nature, before he bedded down one night he locked open the lens on his camera to make overnight a time exposure of the stars. The problem was that he overslept until the sun had come up and burned an open wound, like a knife cut, right thru the negative. Realizing that such damage could be used in creative ways, he then began recreating the effect directly on enlarging paper rather than a negative. Making his exposures at different times of year, he has used the sun as his stylus to draw on the sky straight lines, arches, S-curves . . . even a perfect X, as if cancelling out the sky altogether. Or, by opening and closing the lens at intervals, he shows us a sequence of black suns cascading down the sky and reflecting off San Francisco Bay below.

Marco Breuer also attacks print paper physically sometimes, laying on it a cloth that he lights on fire, abrading it with a palm sander or steel wool, etc. An exceptionally mesmerizing result was achieved when he put a sheet of chromogenic paper on a turntable and cut a record, as it were, by letting the needle scratch a vortex of a groove into the paper. The turntable is of course another obsolete technology, as are movies projected from reels of film, broadcast TV and hard-copy magazines. In 1992, Breuer isolated himself from the last three after finishing his academic studies. He did so in order to make a fresh start with photography, to “purge” his imagination of all other visual technologies. But one other visual technology was available then that he doesn’t mention – the computer.

In 1989 Sir Tim Berners-Lee had invented the World Wide Web and thus helped PCs become standard equipment on desktops everywhere by the early 1990s. Did Breuer have one of those? He was “minimizing input” in order make photographs for 100 days, during which he realized he could create images not only in the light from embers in his wood stove but by placing a red-hot ember directly on print paper. Like other practitioners in this exhibition, he progressed backwards into ever more elemental and primitive forms of photography. Before his 1992 experiment in isolation, the last and longest course of study he undertook included the history of printmaking as well as photography. This, perhaps, has allowed him to reflect on ways in which the invention of photography made prints and antiquarian art form much as digital photography was about to make traditional photography an antiquarian practice too.

The two other photographers in the exhibition – James Welling and Matthew Brandt – book-end it in the sense that they are not only the oldest and youngest included, but know each other well because they were teacher and student in the UCLA MFA program. (I should mention that I also know both well because in 2008 I taught a graduate seminar for Welling in which Brandt was a student.)

Welling has a gift for teaching partly because his own varied and seemingly eclectic projects as a photographer have in fact been a pretty systematic exploration, or interrogation, of the history of photography. One of the three projects of his illustrated by the exhibition entailed exposing chromogenic paper to sunlight. For another, he exposed chromogenic paper in a tray of water beneath a color enlarger head. And for the third, performed in the ambient light of his studio, he applied black and white developer and/or fixer to chromogenic paper. All three resulted in swirling abstractions, but this last has a built-in poignancy because the prints will continue to darken until black. “Photography is,” Welling says, “the process of tarnishing silver.”

The first time I met Matthew Brandt, he seemed by nature a cross between the droll conceptualist Bruce Nauman and the photographer manqué Vik Muniz. And his work has indeed contained the literal-minded, Rube-Goldberg qualities of those photographers. His work has been ridiculously literal in the sense that his prints are not just the photographic image of the subject; they incorporate into the print some of the physical reality of that subject. For a series of portraits of friends he began while still at UCLA, he used one of the two forms in which photography’s invention was announced in 1839, the version pioneered by English aristocrat William Henry Fox Talbot in which both the negative and the positive were on a piece of salted paper. Brandt’s innovation was to prepare the paper by including in its chemistry a bodily fluid provided by the subject – saliva, tears, breast milk . . . sperm. He also made at one point a photograph with cocaine in the mix.

Matthew Brandt, American, born 1982, 00036082-3 “Mathers Department Store, Pasadena, 1971”, 2013, Gum bichromate print with dust from AT&T parking structure level 2

More recent work includes a copy Brandt made of a 1971 photograph of the demolition of a department store. His greatly enlarged print has for two reasons the hazy look of something lost in time: first, because Brandt used a nostalgia-tinged Pictorialist process originally employed in the 19th century to idealize landscapes and other eternal subjects, and second, because he enhanced the print’s fading-away effect by mixing in dust he collected off the street where the store once stood. Opposite that image is one equally large of a dinosaur skeleton photographed at the La Brea Pits’ Page Museum and printed with some of the tar from the pits outside. The use of the tar was not a gratuitous gesture, for Brandt synthesized from it the Bitumen of Judea that Nicéphore Niépce used in creating the first photograph ever in 1826 or 1827.

Matthew Brandt. Rainbow Lake, WY A20, negative 2012; print 2013, Chromogenic print, soaked in Rainbow Lake water (30 x 40 in.)

For his most widely known series in the exhibition, “Lakes and Reservoirs,” Brandt brought back from each lake he visited with his camera a large jug of lake water in which he immersed his photographs of that lake immediately after printing and fixing them. The result was to unfix the chemistry and obscure the putative subject behind translucent veils of color. We are taken aback precisely because, enhancing the reality of the print in such an absurdly literal way, Brandt has turned the image into an abstraction. This is not the least of the paradoxes that are entertained in this exhibition, and with which it entertains us. On the far wall of the last gallery, the youngest photographer has been permitted to write the exhibition’s punch line with one of his lake photographs.

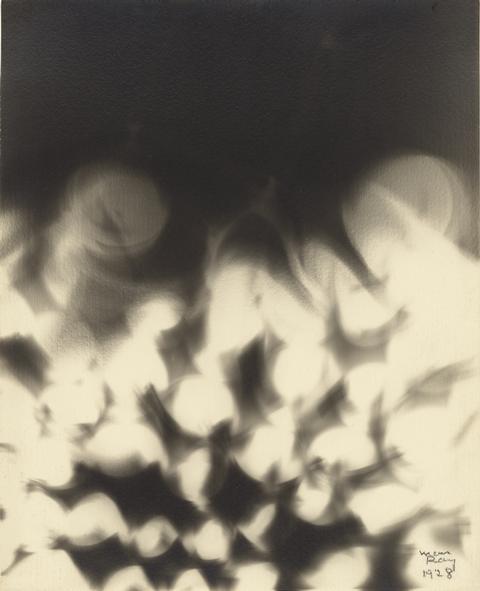

Man Ray (Emmanuel Radnitsky) American, 1890–1976, Untitled (Smoke), 1928, Gelatin silver print (9 11/16 x 7 13/16 in.)

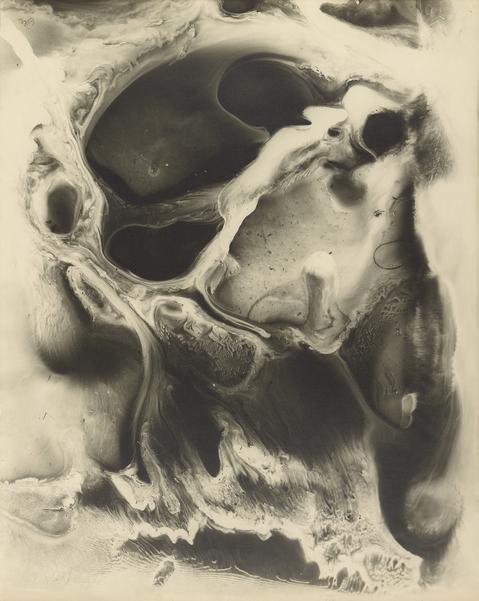

Chargesheimer (Karl Heinz Hargesheimer) German, 1924–1971,Picturesque, 1949, Gelatin silver print (19 1/2 x 15 9/16 in.)

In addition to showcasing the break-through work of these contemporary photographers, the exhibition is itself a break-through for the Getty’s Department of Photographs. The first gallery in the exhibition is installed with relevant historic work from the Department’s peerless collection – photographs like Chargesheimer’s “Picturesque,” 1949, that resonates with Welling’s “Chemical,” 2009, or Man Ray’s “Untitled (Smoke),” 1928, because it prefigures Oppenheim’s 2012 prints from 1944 documentation of smoke rising in the wake of a bombing run. But the department’s exhibition program has been distinguished by shows drawn from a collection with such historical depth and breadth that, ironically, it has sometimes seemed stuck in the past.

This is not to say that there haven’t been fine shows of work by photographers who were still working. But as Getty Museum director Timothy Potts notes in his foreword to the catalogue, “This book and accompanying exhibition . . . fast-forward to artists of the present whose engaged interrogation of photography challenges us to see the medium with fresh eyes. . . . [T]he exhibition marks the first time that the galleries of the Center for Photographs are dedicated primarily to . . . works made within the last fifteen years.” The credit for this unprecedented development has to go to curator Virginia Heckert, who is the first head of the Department of Photographs not to have been present at the creation in the mid-1980s. Her show represents a significant expansion of the department’s horizons.

The J. Paul Getty Museum

April 14 – September 6, 2015