Your cart is currently empty!

Author: Isabella Miller

-

Nick Angelo

Sebastian GladstoneA big pharma scion funded the Tolkien exhibition at Rome’s National Gallery of Modern Art to normalize drug dependency by suggesting its correlation to Bilbo Baggins’ obsession with the One Ring. Or, hear me out, Whiskey Pete’s casino operates a mind-control project disguised as immersive art using data from an addiction treatment center’s experimental therapies.

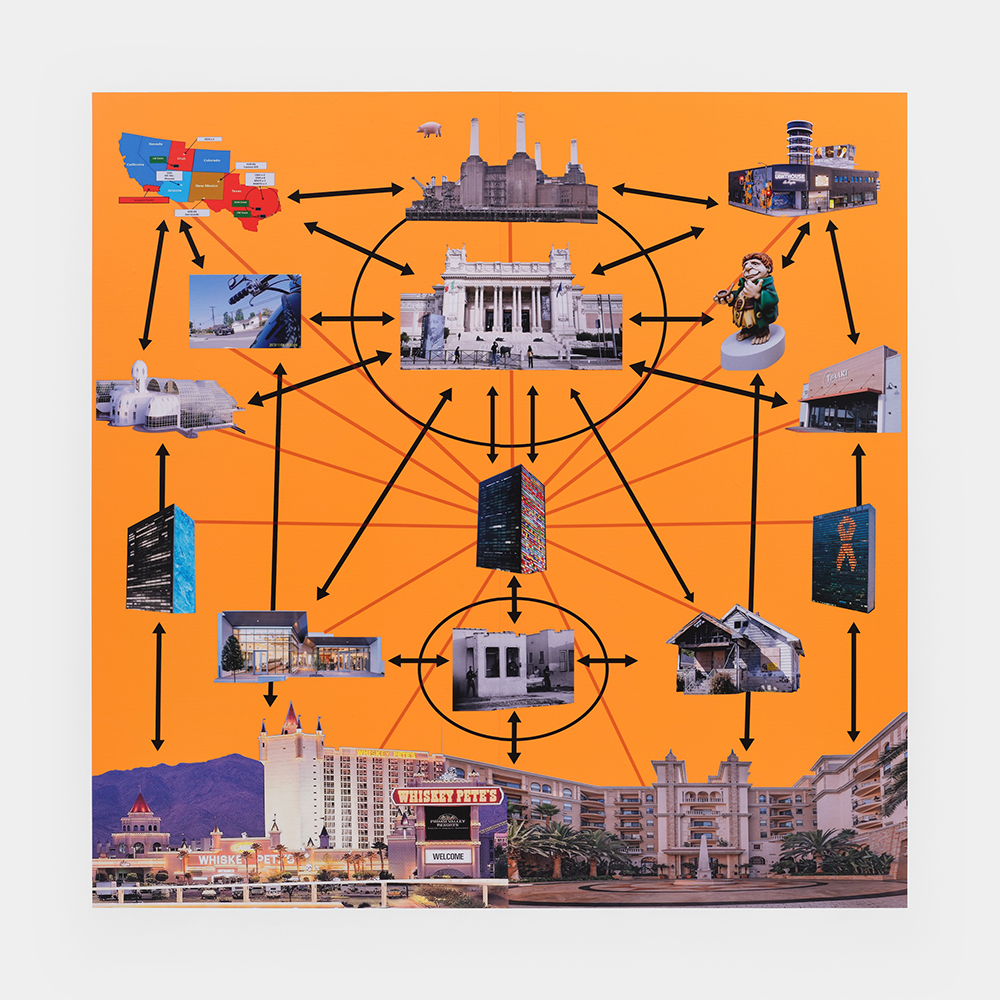

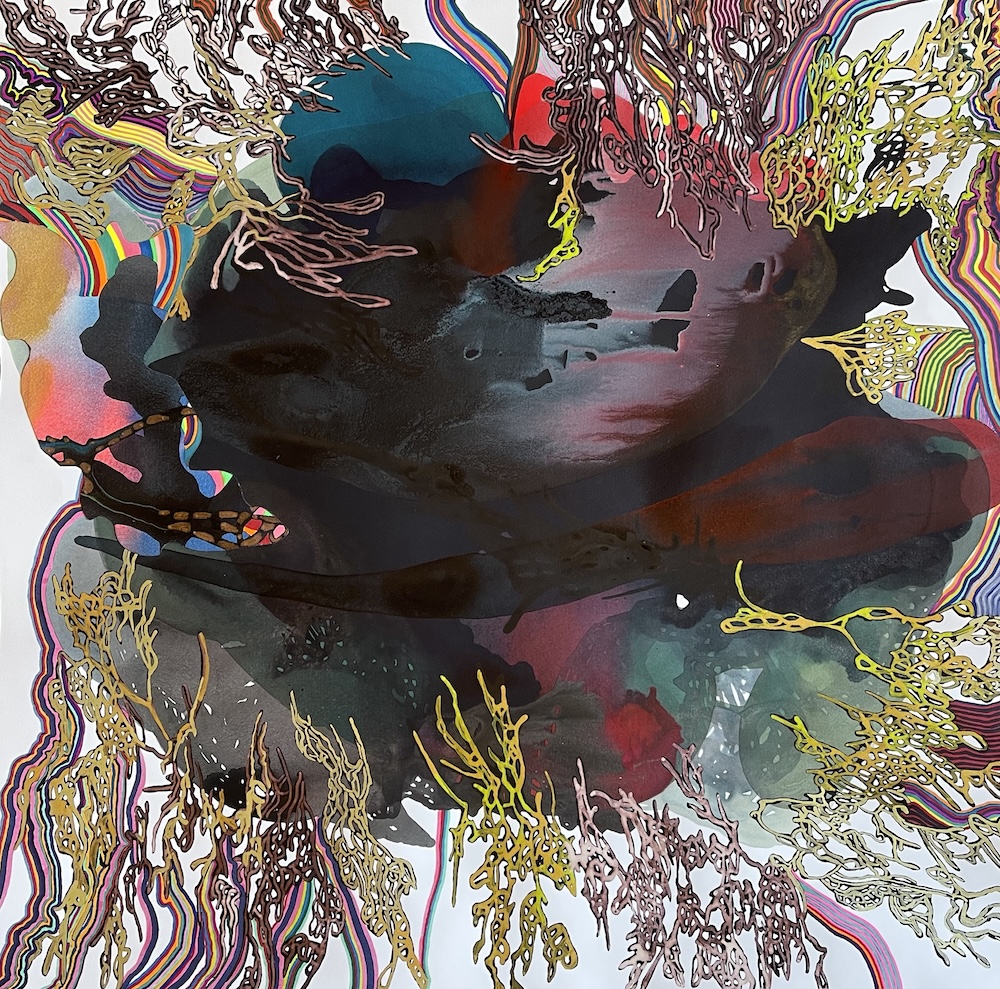

These are two of the many conjectural rabbit holes one might go down while trying to parse the meaning of the large-scale vinyl sticker A Conspiracy Theory About Jade Helm 15, JRR Tolkien, The Van Gogh Exhibit Where Amoeba Music Used to Be, And Other Things (all works 2024), in which both the National Gallery and Whiskey Pete’s are featured. The work, installed in Sebastian Gladstone’s main gallery, presents a flow chart on an orange ground with images of sites (also including a former Symbionese Liberation Army safe house, the ecological research facility Biosphere 2 and a Luxe fitness center) linked together in a byzantine network of arrows, lines and circles. The diagrammatic structure appears in another acrylic-on-aluminum work, Blue Opal, which connects various buildings and objects—from a leather office chair and a treadmill to an industrial plant, a prison fence and a stately manor—on a grid resembling an architectural blueprint, manifesting a desire to expose unseen infrastructures and systems of authority. It also structured the exhibition, as a series of long black arrows were printed in vinyl on the wall, moving the eye from one work to another.

Nick Angelo, A Conspiracy Theory About Jade Helm 15, JRR Tolkien, The Van Gogh Exhibit Where Amoeba Music Used to Be, And Other Things, 2024. Courtesy of Sebastian Gladstone. Angelo’s invocation of icons, such as arrows, lines, circles and grids, elicits the sensation of conspiracy rather than offering a coherent ideology. This creates a kind of intellectual temptation on par with the gustatory temptations presented in the sumptuous, Dutch-style vanitas of fruit, bread and cheeses titled My God, Does He Eat Alone! (After Floris Claesz van Dijck). Angelo, who for years has meditated on the political, cultural and socioeconomic conditions of contemporary addiction (and who works with Community Health Project Los Angeles to provide clean needles to drug users), suggests in his work that conspiracy is another desired object that one might become addicted to.

This exhibition, “La Pensée Unique,” channeled much of what it feels like to wade through true and false conspiracy theories as we seek to understand the corporate and national interests that structure our lives. Because the actual network of power that perpetuates illness, addiction and poverty is complex and diffuse, having a stable theory of it is a kind of fantasy, much the same way that a dollhouse (an object Angelo explores in his dollhouse-like sculptural miniature A Celebration of the Union of Dr. Kris Kelvin and TINA Caruso, One for the Ages) fulfills a wish of stable domestic life. Angelo’s exhibition captured this conspiratorial impulse while also resisting its fruition. Instead, his work reflects on the abstract mechanisms and strategies of power that undergird those that are both visible and implied.

-

Alicja Kwade and Agnes Martin

Pace GalleryThe sprinklers of Pace Gallery’s immaculate lawn activated as I entered its courtyard for “Alicja Kwade & Agnes Martin: Space Between the Lines.” One of them was installed only a few inches from Kwade’s Jo’s Snow (Group 2) (2023), a forlorn patch of cast white marble in the shape of shoveled and half-melted snow, and water dribbled down the sculpture’s pocked side. Several iterations of Jo’s Snow were stationed in various states of paralyzed dissipation around Pace’s lawn. They languished in the sunlight, monuments to time’s inexorable passage, collecting dust and dried leaves. “My efforts to understand and represent something I can barely grasp, and my failure to do so, bring forth my work,” the Berlin-based artist has commented, a sense of stymied understanding that was palpable in the pieces on view here. The Canadian-born Martin, whose work is now inextricably entwined with the austere, parched landscape of the American Southwest, also made art that probed the edges of conscious understanding, although the lightness illuminating her meditative paintings and works on paper contrast sharply with Kwade’s ruminative installations. This two-person show explored how both artists embrace mundane ephemera–clocks and grids among them–to encounter the void.

The largest gallery featured Kwade’s enormous twin sculptures, Distorted Day and Distorted Dream (both 2024). In both works a curving, lacquered black plane of steel, reminiscent of Richard Serra’s COR-TEN steel installations, cleaves the air between rectangular metal frames; a large stone appears to float, meteor-like, on the supports before each arch. Warped mirror images elongate and then disappear along the sculpture’s inky curves. Kwade plays with suspension and immobilization to emphasize our perceptual limitations; the mirror rebuffs as much as it reflects.

“Alicja Kwade and Agnes Martin: Space Between the Lines.” Photo: Jeff McLane. 1201 S. La Brea Ave., Los Angeles, 90019. May 18 – June 29, 2024. Courtesy of Pace Gallery. The sole black painting among Martin’s considerable oeuvre, The Sea (2003), which was painted a year before her death, hung on an opposite wall. Slender white lines gleam across the canvas at intermittent weights, creating a shimmering effect akin to light breaking over water. Before embarking on her artistic career, Martin had trained to become an Olympic swimmer, and something of that gliding, repetitive motion can be seen in her paintings, as does the sense of submersion and tranquility. The artist has talked about looking at a painting as entering “a field of vision as you would cross an empty beach to look at the ocean.” The Sea’s rhythmic intervals of negative space, with its lost and found lines, likewise refutes containment. Her meticulous grids express the transmutation of duration into eternity, opening outwards in waves. Both artists reckon with time as something essentially beyond human grasp, even as we are swept away by it with the passing of years.

The next room provided more entropy from Kwade—a clock ticking in the wrong direction, and a melted mirror sliding onto the floor—while Martin was represented by an untitled etching (dated 1960), whose inconstant lightness gives the impression of a weather event occurring inside its spare grid. 220 Days (2014/2024) by Kwade travels across all the walls in an undulating line of miniscule brass watch hands, marking the passing of time in six-hour intervals. At the right angle, they vanish from view entirely.

-

Melanie Pullen

William Turner GalleryImages of violence are so prevalent in today’s media landscape that news commentators now prompt us to look away, while social-media clips of police misconduct or war-ravaged bodies are shared and reposted, implying that we might take voyeuristic pleasure in viewing them. Melanie Pullen was certainly aware of our collective fascination with morbidity 20 years ago when she produced her series “High Fashion Crime Scenes,” staged photos based on actual forensic records and documentation of pre-1950 “Jane Does:” murders or suicides that were never solved. A lover of film noir and French New Wave cinema, Pullen hired a film crew to realize her scenes with elaborate lighting and staging over month-long shoots. To underscore her premise that the entertainment industry glamorizes violence, she dressed her models, posed as corpses, in expensive designer clothing and accessories.

Six of these photos were included in Pullen’s new exhibition at William Turner Gallery, along with four from a more recent 2018 project, “Voyeur.” While both series are highly seductive in their use of color, mood and narrative implications, they differ in other ways. In the cold-case scenes, Pullen’s femmes fatales are victims, while in the newer works they are active protagonists equipped with binoculars, their intentions either heroic or villainous. While the earlier group encourages viewers to act like private detectives as we imagine what took place, the models in some of the newer works look directly back at us. We are no longer investigators: We are the watched.

Melanie Pullen, The Watcher (Voyeur Series), 2018 Inkjet archival print, mounted on aluminum, Courtesy William Turner Gallery. Part of the appeal of Pullen’s photographs is that they use intense or obscured lighting to focus or divert our attention in the way a cinematographer would. In Yellow Cab and Yellow Street (both 2003), the dead bodies emerge before us gradually, their silhouettes barely detectable amid darkness which contrasts sharply with brightly illuminated areas of yellow. Conversely, the corpses in Untitled (2004) and Ferris Wheel (2004) are well-lit and positioned in the lower foregrounds to lure us into each scene. The green-tinted untitled work, which takes place in a metro station, exudes an uneasiness, as three possible escape routes for the murderer—a train and two escalators—would normally be moving but appear paused mid-motion, creating an uncanny sense of quietude. Meanwhile, Ferris Wheel conjures associations with familiar movie lore. The view of Pacific Ocean Park in the background recalls the setting for attempted murder in Alfred Hitchcock’s Strangers on a Train (1951), while the victim’s red garment suggests the comedic heroine from Gene Wilder’s The Woman in Red (1984).

Lighting also plays a pivotal role in dramatizing the “Voyeur” series. Los Angeles’ drive-by culture is referred to in colorful streaks from car lights that create visual barricades in The Stalker and The Watcher (both 2018). More importantly, the women behind the binoculars in She Sees Everything (2018) and Watcher, in Red (2018) are dressed to the nines and appear powerful, confident and fearless. With her subjects now looking like Barbie’s still carefully coiffed but newly self-actualized heroine, Pullen is clearly in step with the cultural shift catalyzed by the “Me Too” movement.

-

30th Anniversary Group Show

David ZwirnerOn a murky day in May, the art cognoscenti made their way to a preview of gallerist David Zwirner’s newest addition to his burgeoning enclave in Los Angeles. Among the city’s unremitting attempts at reinvention, Melrose Hill—a longstanding, dense and vibrant community—has suddenly become its newest gallery (and culinary) destination. The neighborhood possesses the merits of being a partial Historic Preservation Zone, and its current residents are largely Latino, South Korean and Thai. Its landscape is distinguished by a number of unique 100-year-old buildings—and now by galleries, as well as a ghost kitchen to service food-service delivery customers.

With this one, Zwirner’s complex now totals three buildings, and the new gallery features a 15,000-square-foot Modernist edifice by Selldorf Architects, who proclaim an approach “rooted in the principles of humanism.” The result is a rather restrained facade. But its interior is beautifully realized with voluminous spaces, meticulous finishes and washes of natural light throughout. The noteworthy revelation was this 30-year survey of the gallery’s artists, which read as a “who’s who” of modern and contemporary art history, both Angeleno and international.

Upon entering one encountered Raymond Pettibon’s (No title (Procreation extended to…) (2017). There are other American gems, such as Roy DeCarava’s elegant George Morrow (1956), a silver gelatin print of the jazz bassist. DeCarava was a photographer known for chronicling the daily life of the Harlem community and its musicians. Michaël Borremans’ enigmatic portrait, The Talent (2024), is a vaguely unsettling and ambiguous work carrying an Old Masters sensibility into contemporary discourse. The artist lives and works in Belgium and is probably best known for his controversial 2018 “Fire from the Sun” exhibit the gallery mounted in Hong Kong, which featured blood-splattered, cherub-like toddlers, ostensibly engaged in playful, furtive and possibly violent acts.

“David Zwirner: 30 Years,” installation view. David Zwirner, Los Angeles, May 23–August 3, 2024. Courtesy of David Zwirner. A catalog from that exhibit was randomly included in an ill-fated Balenciaga media campaign photograph that precipitated all manner of handwringing. Dana Schutz, who has also courted controversy with her painting of Emmett Till in 2017’s Whitney Biennial, was represented here with Family in a Wave (2024), a densely gestural, expressionistic work with a disquieting narrative in which family members are depicted semi-submerged under a massive wave while their children play.

But serenity prevailed with Ruth Asawa’s lovely copper-and-brass hanging sculpture, Untitled (S.765, Hanging Five-Lobed Continuous Form within a Form with a Large Open Collar and Three Interior Spheres) (c. 1952–53). It was a graceful, lissome presence in a sea of disparate styles and mediums that span the gallery’s three decades. The ensemble suggested an impressive trove—a mark of Zwirner’s ongoing, comprehensive commitment to his artists and collectors.

This expansion has been exceptionally rapid, solidifying LA’s reputation as a major art center. And Zwirner isn’t alone, as several New York–based galleries, including James Fuentes, Clearing and Sargent’s Daughters, have joined the westward move. In Melrose Hill, the local response to rumblings of gentrification seems somewhat muted, with residents more curious than anything else. Nevertheless, this micro-economic “train” has already left the station.

-

Coco Young

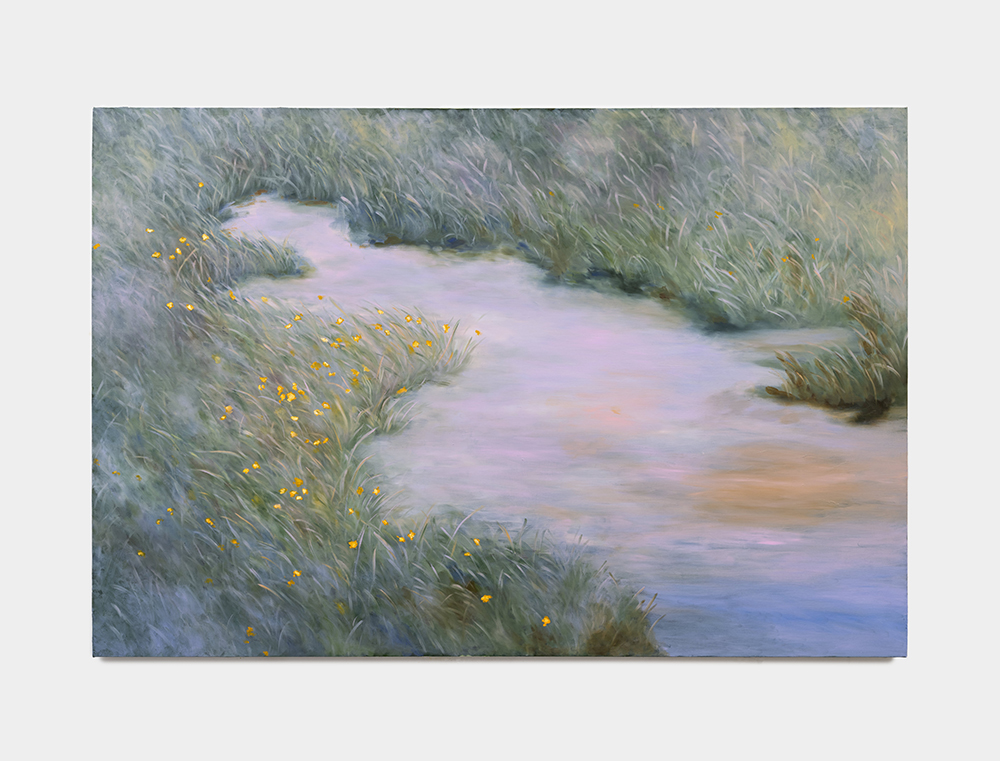

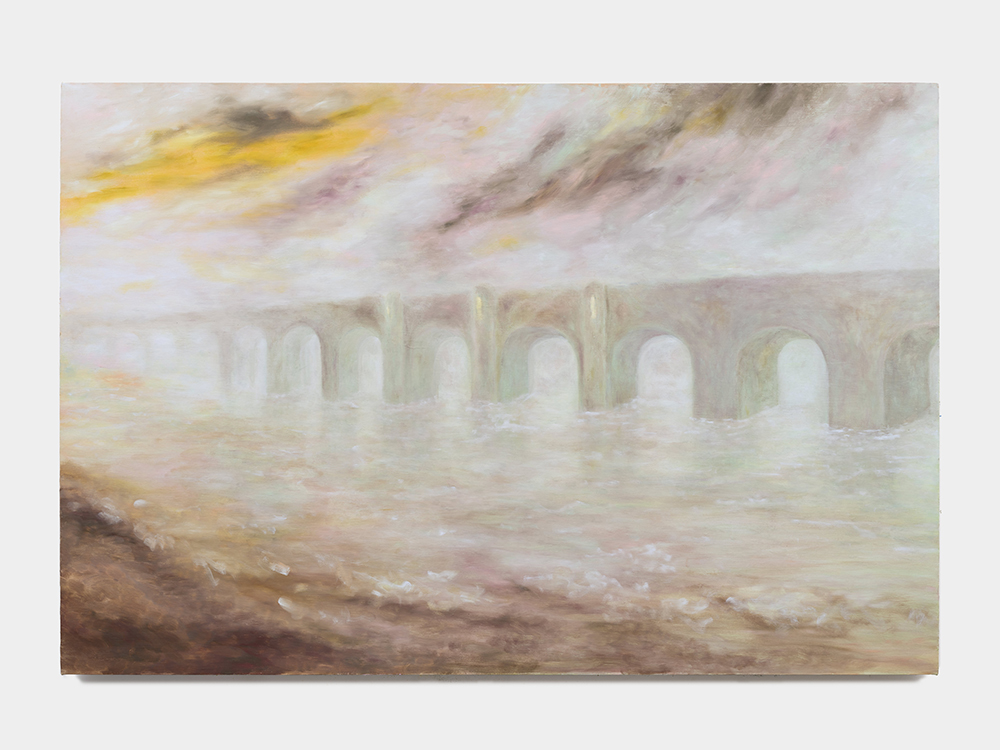

Night GalleryMelancholy rendered in pools of soft, golden sunlight. Love and loss braided into fields of wildflowers. In the press release for “Passage,” Coco Young’s first solo show at Night Gallery, curator Martha Kirszenbaum compares the exhibition to Agnès Varda’s lush New Wave film Le Bonheur (Happiness) (1965). Numerous scenes in the doomed filmic love-ballad feature flowers shown in bloom or cut down and presented as bouquets, reminding the audience that they are present both in times of love and death.

Young’s ethereal oil paintings—misty fields of yellow, blush and ivory—are similarly romantic, nostalgically steeped in reminiscences of her childhood in the sun-drenched south of France, in which she immerses her viewer. Looking at her painting Bog at Dawn (all works 2024), I feel simultaneously tucked into the soft, tangled fallow captured in the early morning’s glinting sunlight, as well as fully awake with the restlessness of youth. In Le grand ruisseau, lost in an emerald meadow freckled with delicate scarlet bossoms, the artist leads me along the banks of a meandering river, the stillness of the afternoon shown in its reflection. In The Pond, which depicts a herd of red-tinted swans, possibly stained by blood or reflecting the warm light of daybreak, I am reminded of the Greek myth Leda and the Swan, in which Zeus transforms himself into a swan to seduce a naïve Leda in a perverse act of deception. Meanwhile, the sole human figure in the exhibition appeared in Yasmin, whose subject reclines idle and patient in another idyllic pasture. Flecks of gold and peach suggest that it is spring, but the girl’s expression is difficult to read. In many of Young’s paintings I find this duality and am seduced.

Coco Young, Passage, 2024. Credit: Zashan Ahmed. Courtesy of the artist and Night Gallery, Los Angeles. Kirszenbaum writes that the show’s title refers “to a possible transition from one world to another: childhood to adolescence, life to death.” Yet it feels insufficient to compartmentalize the existential fleetingness that Young portrays in this work. She reminds us that the wrenching, awkward transience of youth is not at odds with one’s life but rather crucial to its development; that we remain in a state of constant transition.

What Young delineates is the impact of what her childhood might have been like. Her impenetrable nostalgia, the core of our shared sensation, the spark in our internal quiet dramas we so dearly miss. With her urgent yet gentle hand, Young captures the sense that our interior selves are as turbulent as the storm clouds over the show’s titular river. The exhibition creates a haze of an eternal spring and honeysuckles, reminding us that nothing will ever be this sweet again.

-

pascALEjandro

BlumThe nonagenarian artist Alejandro Jodorowsky is best known as a filmmaker, while his wife, the 40-something Pascale Montandon-Jodorowsky, works as a painter, photographer and designer. Together, they operate under the name pascALEjandro, fusing their names as well as their sensibilities to create colorful works on paper they cumulatively refer to as a “spiritual child born of love.” In these works, Pascale applies color to Alejandro’s illustrative lines. The 20-plus works gathered for this show create fantastical narratives when seen together. Many feature two characters—a male and a female—who traverse surreal settings. There are images of death and love, struggle and escape. As the duo states in the show’s press release, “Our working material is the material of our lives … pascALEjandro is the synthesis of two beings, who form alchemy’s androgynous union.”

In The Essential Point (2016), two figures float on their sides, hovering in a blue-green sky above a green hillside, their outstretched pink tongues meeting at “the essential point.” The woman’s arms have been replaced by yellow-orange wings, which support her tent-like body while her long hair dangles limply below; her eyes and that of her partner, who wears a purple hat, are interlocked. In contrast to this beatific coupling, The Difficult Union (2021) depicts a barren desert landscape, in which a man and a woman push gray carts toward each other. One carries a giant orange hand, the other supports a hand that is yellow. The bare feet of both figures have been nailed to the ground, making movement of bodies and carts alike impossible. Yet it appears as though the hands join forces to assist them in some way, as the orange fist belonging to the woman clutches two fingers on the yellow hand emerging from the man’s cart. In this work, pascALEjandro tenderly probes the difficulties and complexities of partnership, and the importance of working together no matter what the situation.

pascALEjandro, The Essential Point, 2016. © pascALEjandro. Courtesy of the artist and BLUM Los Angeles, Tokyo, New York. PascALEjandro Forever (2021) is a collage that features a black-and-white photograph of the couple hugging. The photo is encased in a drawn tombstone marker that emerges from a beehive populated by 3D facsimile bees that surround the couple in a light blue, cloud-filled sky. This work is hopeful as well as commemorative. It illustrates pascALEjandro’s enduring love, as well as their significant difference in age. This theme is revisited in March against Absence (2016), in which two figures battle a wind that causes buildings to tilt and wooden chairs to be tossed and turned in every direction. The man, a clown or jester, holds the hand of a younger masked girl with a red balloon, helping her navigate the elements.

The pictures were installed close together so that related images inform and create a quasi-narrative. While individual pieces stood out, the overarching feeling of love and connection, regardless of circumstance (be it prosaic, imagined or allegorical), shone through most brightly when they were taken as a whole. The works are delightful and enchanting, albeit also uncanny and strange as viewers tried to navigate the particular relationships between man and woman, demon and beast, and real and imagined worlds that are illustrated through exacting and confident lines.

-

Simone Leigh

LACMA and CAAMSimone Leigh’s presence at the 2022 Venice Biennale was monumental: Her sculptural contributions to the main exhibition garnered a Golden Lion, while her solo show for the US national pavilion generated headlines around the world and lines around the block. In the context of that venerable site—and particularly in terms of Biennale curator Cecilia Alemani’s focus on global feminist surrealism—Leigh’s engagement with Western art history and juxtaposition of canonical and vernacular materials (bronze, gold and ceramic paired with straw thatching, wire and cowrie shells, for example) achieved a profound aesthetic impact and delivered a searing postcolonial critique.

Leigh’s blending of ancestral legacies and diasporic modernity; her infusion of personal perspective into a broader conversation on feminism, race and oppression; and her frankly magical way of crafting shimmering, beckoning, impassive yet impassioned objects of exquisite beauty are leveraged to excavate a dark set of histories. All of that power and grace was on display in Los Angeles this summer when her post-Biennale traveling survey, which orginated at ICA Boston and includes selected works from Venice, finally arrived. This local iteration was shared between two institutions—LACMA and CAAM—each with their own cultural directives and architectural and historical contexts to work with.

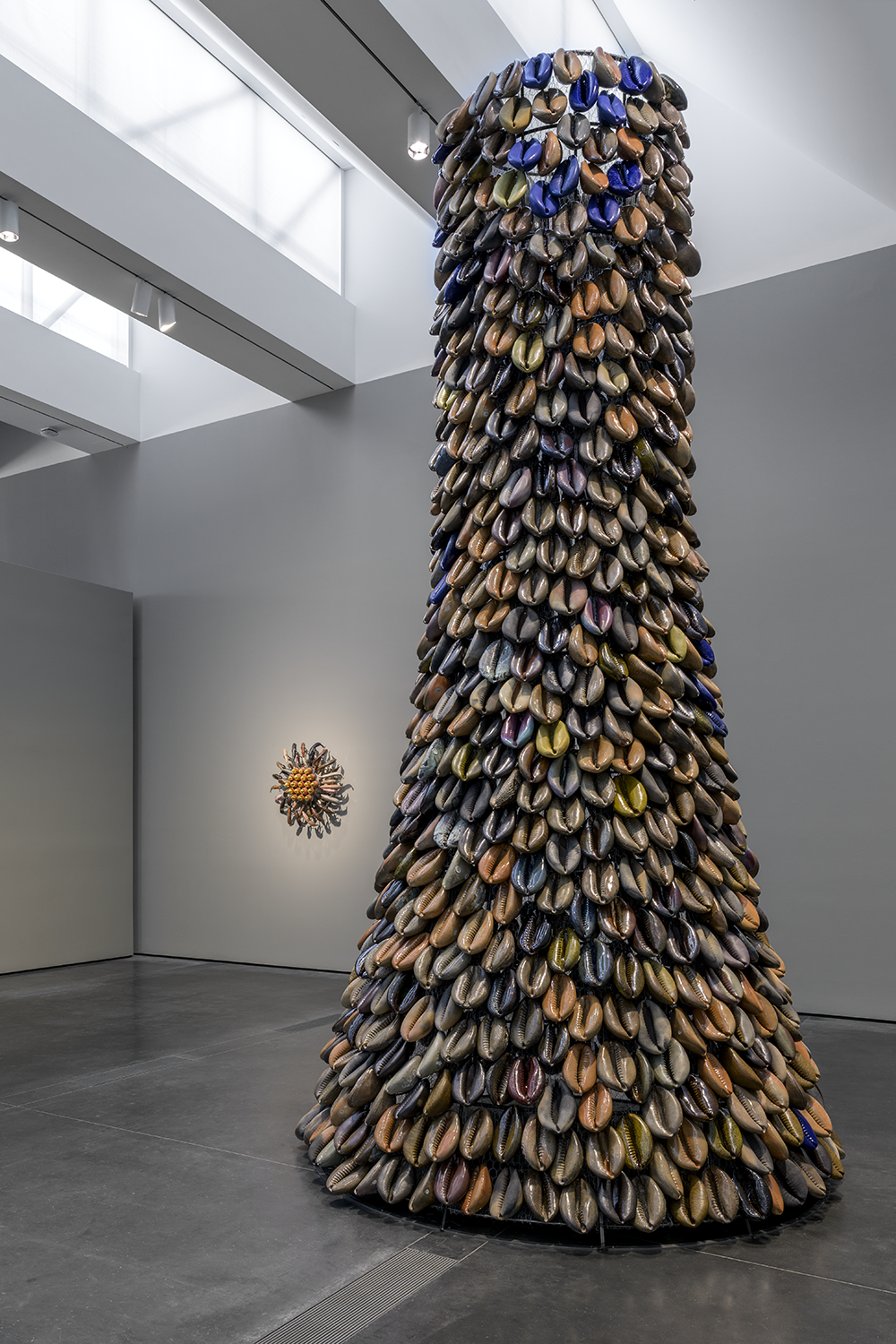

At LACMA, whose mission is to present an expanded global art history, a pair of stoneware Sphinx statues (both made in 2022, one of which appeared in Venice), rested on the floor framed by wide windows and a distant palm, adjacent to a reflecting pool—an inspired curatorial choice. Leigh reclaimed the mysterious feminine guardian energy of the Sphinx in ancient North African mythology while infusing the figures with alluring physicality, activating site-specificity to confront, rather than adorn, a seat of modern cultural power. Untitled (after June Jordan) (2024) is a monolithic 16-foot tower crafted in steel, hex mesh, stoneware and porcelain in the form of hundreds of large, richly glazed cowrie shells—a recurring motif that acts as a symbol of bounty, wealth and fertility and illustrates her evocation of ancestral matriarchy in imagining a more nurturing future.

Simone Leigh, Cupboard, 2022. Photo: Timothy Schenck. Courtesy of the artist and Matthew Marks Gallery. © Simone Leigh. While LACMA’s curatorial eye is cast in the service of a wider survey, CAAM’s is more closely attuned to renovating the canon to include previously marginalized voices, foregrounding especially the richness of the African American cultural presence in Los Angeles. The monumental Cupboard (2022), with its 11-foot-tall, chapel-like figure of stoneware, raffia and steel armature, had its own intense gravitational pull; its dazzling counterpart, the gilded, seven-foot bronze Cupboard (2022) was installed outside the museum’s entrance. Both of these works, which exemplify Leigh’s affection for pre- colonial mythologies, spiritual practices, materials and techniques, were exhibited to wide acclaim in Venice. Inside the gallery,poignant earlier works relayed more biographical narratives, and two video pieces and a ceiling-mounted light sculpture made explicit connections to contemporary popular culture.

The choice to distribute the show’s relatively small number of works (about 30 pieces in total) across two locations also meant that each installation was relatively sparse, and all of the galleries were dramatically low-lit, some by the flicker of video projections, creating a meditatively paced pathway through the rooms. With such uncommon power, and its command of all the requisite visual languages, including its unapologetic embrace of beauty, the work occupies all of these spaces—literally and figuratively—even as it continues to open new ones.

-

PICK OF THE WEEK: Winfred Rembert

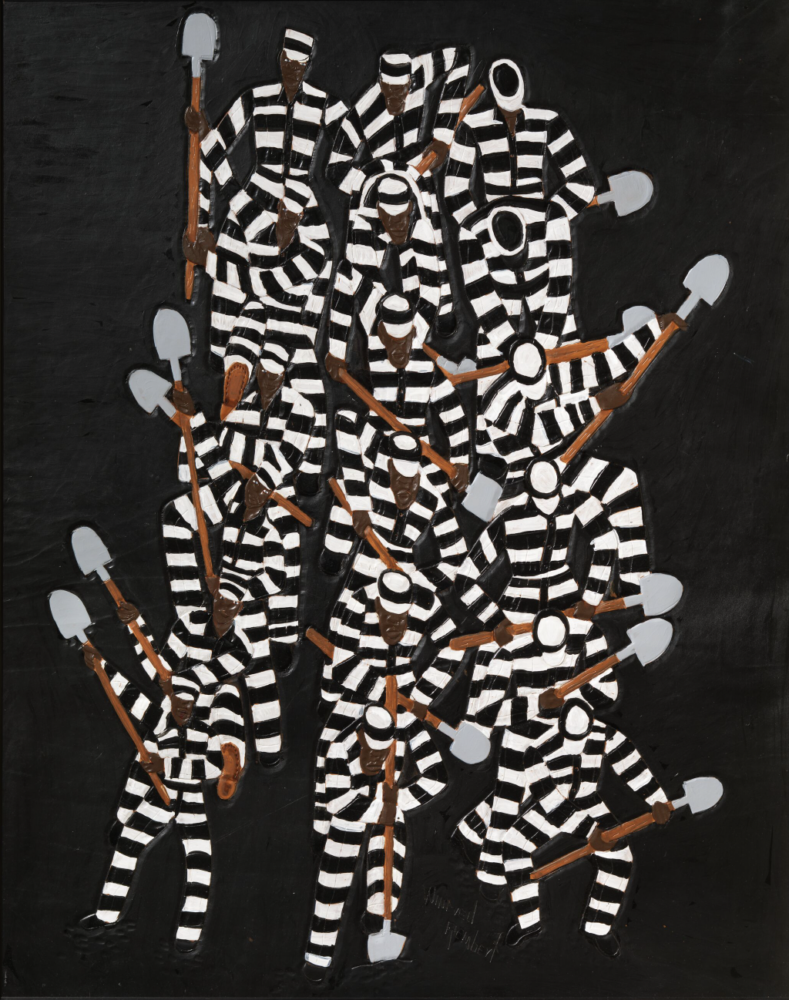

Hauser & WirthA life lived in the midst of harrowing times of chain gangs, sharecropping and Jim Crow laws in the Deep South is the bullseye of Winfred Rembert’s exhibition, “Hard Times.” In hand-carved and debossed painted leather, the late Rembert creates striking patterns from the identifiable violences of our racial caste system: limitless and maze-like white cotton fields, the hierarchical order of plantation life, high contrast stripes of prisoners hammering in the field together and a ridiculous amount of crackling earth moved by prison labor. With respect to the pain of these truths, Rembert is an excellent storyteller, making figurative and metaphorical motifs from bodily dispossession. Despite these scenes being pulled directly from Rembert’s personal experiences, he primarily illustrates his life through groups of people he had once clung to and endured existence with. Amplifying the sense of peril and devastation, he shows us that many others have lived his life too. Here, the act of depicting memory is also the act of depicting history, all the while, his narration becomes a necessary form of witness to suspend the unnatural horror of those times. In punishment’s undoubtedly current and mutated form, Rembert provides a stunning visualization that I fear makes it easy for the unchallenged viewer to avoid a vital question: In the wake of mass and robust maltreatment, how do we meet what we see?

Hauser & Wirth

901 E 3rd St.

Los Angeles, CA

On view through August 25, 2024 -

PICK OF THE WEEK: Paige Jiyoung Moon

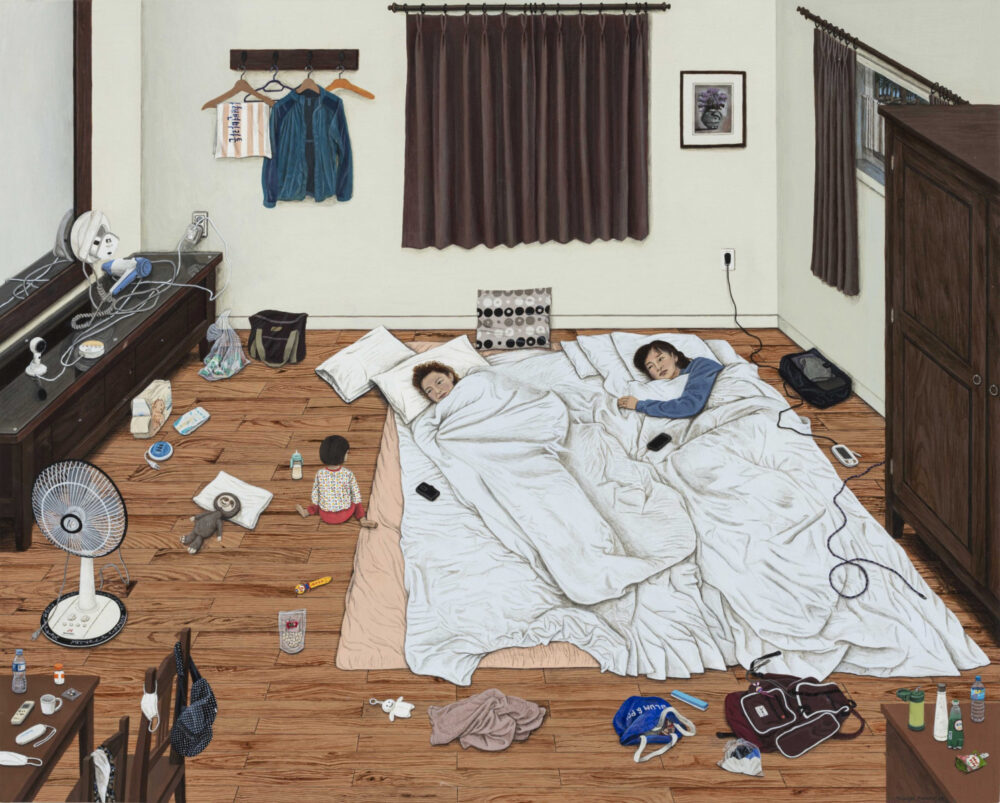

Steve TurnerWith unruffled confidence, Paige Jiyoung Moon’s, “Gen 3” reveals small-scale acrylic paintings depicting informal rituals from her daily life with a profusion of care. Most of the time memories get packed away, but in this case, Moon’s style of painting makes the details of life itself known, allowing audiences to become better observers of life. In Three Generations (2024), two women, likely a mother and daughter, lay in a bed tenderly together with a child nearby. Disorder is upon the bedroom they rest in, where objects are distinctly littered across the surfaces of the room. Each item, from hair dryer, table fan and diapers to backpack, phone charger, Tylenol and many more objects, are imbued with their own narrative space. It’s as if you can picture how they arrived in their tousled state, adding a sense of task in an already busy scene. The amount of stuff Moon fits into a painting embraces inventory in a way that positions the work somewhere between document and memoir. In this hybridity, I sense Moon wishing to create a record of her life, restoring its honorable condition through her subjective nature of reportage. With simple yet highly intricate renderings, it seems Moon begins with painting events to then derive meaning from them as opposed to the other way around. Life differs from painting in that it is brimming with hazy details, however, everything that is included in Moon’s painting summons significance because she directs us towards it and entrusts us with seeing how domestic ceremonies add to the amenity of the world.

Steve Turner

6830 Santa Monica Blvd.

Los Angeles, CA

On view through June 22, 2024 -

Anne Austin Pearce: Her Blue Period

River Deep–Mountain High at Founders Gallery at Soka University, Aliso ViejoWhat is a colorist painter? In the 19th century, the painter and critic Eugène Fromentin assessed that the work of colorist artists engage hues that are “rare, tender, or powerful, but resolutely [achieved by] a man skillful in feeling distinctions, or in rendering them.” Today, colorists might be defined as artists who use striking pigments to ask new questions about art and society: practitioners include Barbara Friedman, whose stunning, funny and risk-taking paintings talk back to the Color Field pioneers, Stanley Whitney, who challenges the canon with his stoplight-yellow and candy-pink grids that quote Agnes Martin, and Jeffrey Gibson, who currently represents the US in Venice with prismatic, multidisciplinary work that comments on Indigeneity, conquest and queerness.

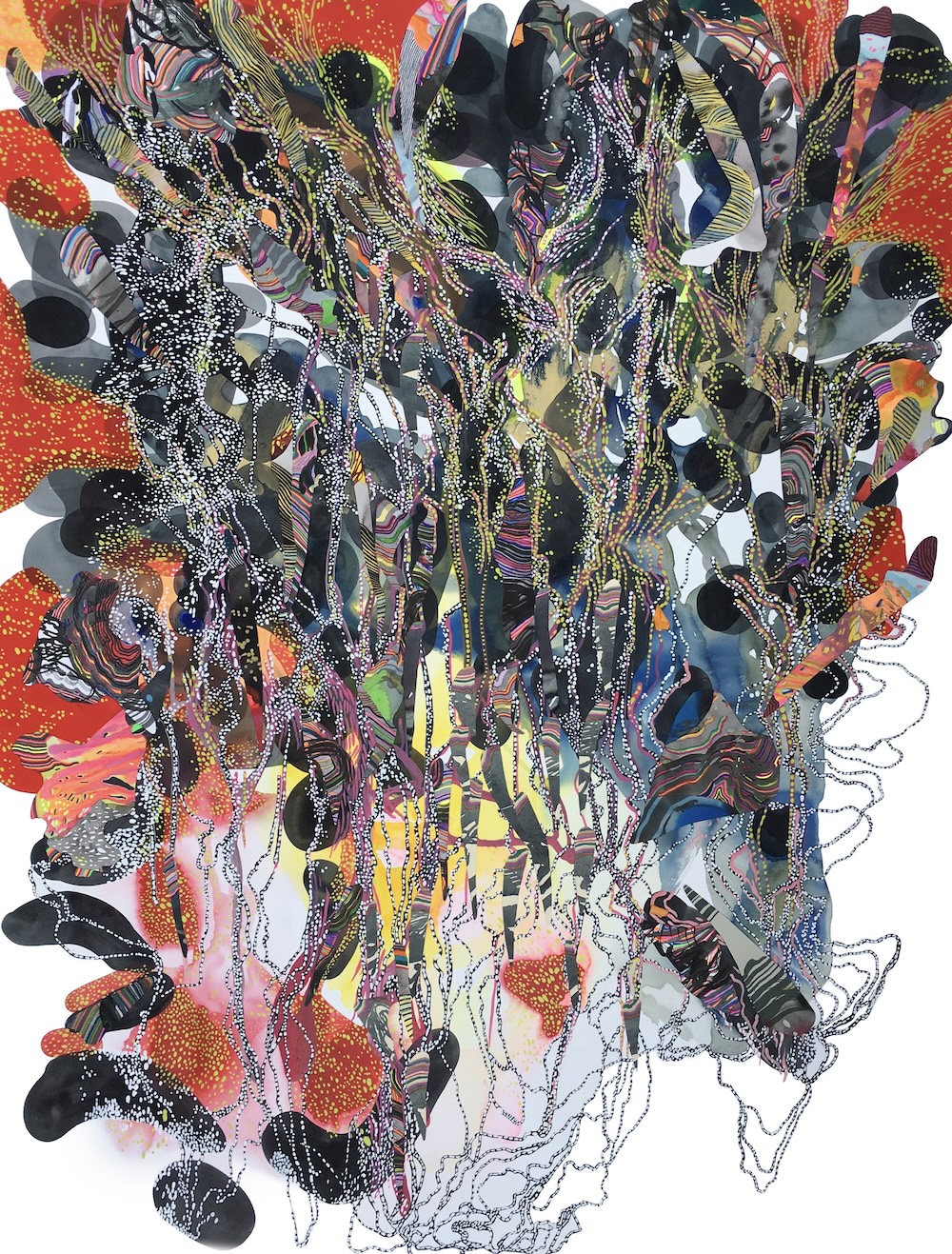

In Southern California, Anne Austin Pearce offers a rousing contribution to this genre of art with “River Deep–Mountain High,” her new exhibition at Soka University’s 8,900 square-foot Founders Gallery in Aliso Viejo. Pearce, who was born in Kansas and received her MFA at James Madison University, has taught art at Soka since 2019 and permanently moved to California in 2020, just around the time that the pandemic hit. In “River Deep-Mountain High,” the viewer is introduced a summation of Pearce’s vivid practice pre-and post-COVID.

Blue, here, is a consistent color, perhaps because Pearce’s university is close to Aliso Beach, a turquoise stretch of the Pacific that was largely empty of people during the most intense periods of the pandemic. This influence is felt in Icarus/Blue Sea (2024), where Pearce has fashioned a massive, swirling work out of cut paper, inks and kaleidoscopic acrylics, assembling these individual painted pieces of papier collé over entire walls of the Founders Gallery until they form hyperreal and amorphous shapes. These swoop across the eye like a flock of birds—or are we looking instead at a swarm of iridescent insects? A tidal wave? Flying dolphins? When enveloped by Pearce’s flowing, flying blue-green-pink-orange-black atmosphere, I felt my heart beating a little harder. It seemed I had entered a strange Eden that existed in a pristine and hallucinatory state—which is not only a reflection on the longing for a more perfect world that struck so many people c. 2020, but also the clear, smogless air that SoCal momentarily “enjoyed” during that weird, grief-struck spring.

Moonlit High Tide, 2023, Ink, acrylic, collage on paper, 50″ x 38″, 2023 This bracing effect is conveyed in Pearce’s other works, which are contained in frames. Such is the case, for example, in Tidal Exit (2023), where Pearce creates a Day-Glo abstract form that could be a mussel bed, an oil spill or roving school of biofluorescent fish. Moonlight High Tide (2023) is a study of sap greens, moss, that dark-black green of magnolia leaves, indigos. and slices of peach and dandelion, evoking a tidal pool churning with amphibious life. San Clemente Gloaming (2023) offers another study in color and multiplicity: Anchored by bright fuchsia, and laced with bitter orange, black, burgundy, mint and tangerine, the collage does not offer the eye a place to rest, but insists on its own abundance, like cell division, birth, or any other struggle for life.

In April, I tracked down Pearce to ask her about her treatment of color, her place in the colorist practice, and the significance of her latest show. She spoke to me between teaching her classes at Soka, where the semester is beginning to wind down in preparation for the summer break.

Icarus / Blue Sea, Ink, acrylic and pen on paper, 2024 XMM: Your paintings and collages have such an acute sense of tone, shade, and color intensity. They’re reminiscent of the natural world but also take part in a contemporary conversation about the meaning of color in today’s society. Why did you decide to make color such an important part of your work?

AAP: Color for me represents resilience; a life force and ultimate joy in the face of the opacity regarding the natural world. I think a great deal about the differences between mediated color and analog color and the tethers to memory, place, people, time of day, and so on. For example, I will choose pink and green because it flings me back to age 17 and seeing someone in OP green shorts with a pink shirt. Color is what drives the emotion that I hope to invoke in my work.Which painters have influenced your approach to color? Did you cut your teeth on Fauvism when you were young? Did you wander into a room of Rothkos at the Museum of Modern Art? Did the Helen Frankenthaler bug bite you?

All of them and more. I like Frida Kahlo and Henri Julien Félix Rousseau and the colors they used to create jungles. While trying to remember my first experiences with color in the context of art, the first and most impactful experience I had was when I was five years and encountered Aboriginal bark paintings located in an apartment loft apartment in Lawrence, Kansas.

Super Hot Heavy, 2020, ink, acrylic and collage on paper, 38″ x 50″

2020Your work seems to have an environmental focus—it’s made doubly apparent by some of the titles of your works. Are you celebrating a nature that has passed, or are you fighting for a future that you refuse to give up on?

Both. Nature is almost like a deity to me, and I seek to observe and admire natural processes in my work; the past, present, and future. I absolutely refuse to give up on the natural world; in nature things die, things evolve, and wonderful new things are discovered.What’s your process like?

I wake early and answer emails from bed where my fine husband delivers coffee. Close the computer and my eyes for a moment and wander around a daydream about the work I left the night before. Unless I am teaching, traveling, or attending a meeting, I paint daily, and I love it.

Spider, 2021, Ink and acrylic on paper, 25″ x25″ Tell us about your journey to “River Deep-Mountain High:” What were you grappling with when making the work that is presented in the show? How were you able to translate the difficulties of the pandemic to such a large space as the Founders Gallery? Also, what spaces informed the work that occupies the show? Did you do research? Did you travel? Did you journal?

The works in the exhibition were started months prior to the pandemic and continued from 2019 – 2022. The world was tumultuous on myriad social levels and by the time the pandemic was in full swing, my life simply rotated between home, the Soka University of America campus and multiple trips the ocean. I treated this time, the newness of the geography and the environment, and regular communion on the campus with animals (deer, skunks, rabbits, owls, red-tailed hawks, coyotes, bobcats, voles, snails and praying mantis) as unique and special. I had to treat it this way because there was no other real option. I tried to make work that was reflective of the actual earth taking a rest and attempted to celebrate other forms of life, such as plants and animals thriving, who perhaps found themselves enjoying newly-found quiet and a bit less pollution.Where you do you get your ideas for paintings? Do you borrow from your life experience? Or are you inspired by your readings? Do you overhear a conversation or listen to the sound of someone laughing and imagine scenes in your head? Or is the process more mysterious, less connected to language?

My ideas are organic and are reminiscent of plants growing between the cracks of a stone path, they appear as small green shoots and evolve. Collecting and observing, experiences layer on one another and continue shape-shifting and re-settling as new ones are acquired.

Tidal Exit, 2023,

Ink, acrylic, collage on paper, 50′ x 64″Describe your practice of liberating the art from the frame and allowing it to travel over the walls. In some ways, this reminds me of the strengths of set design, which create a world that viewers or actors inhabit. What kind of different relationship can viewers have with art when they are not just looking at a framed picture but rather at an atmosphere that is encircling them?

We did not simply step into nature but rather that we came from nature. We humans have fully adopted the idea that we are somehow divorced or unconnected from nature, and that we sit atop mother nature as if we are some unrelated entity, but this is untrue. I hope that liberating the artwork from the frame and allowing it to froth around the audience who see and experience it will rekindle our connection to the natural world.This interview has been edited for space and clarity.

https://www.soka.edu/founders-gallery

Through September 12, 2024 -

PICK OF THE WEEK: Jordan Nassar

Anat EbgiIntertwining tradition, identity and memory, Jordan Nassar’s exhibition, “Surge,” turns large-scale Levantine embroidery and mosaics into sites of tactile continuity, connection and solace. These works serve as a means through which to understand his transnational diasporic Palestinian heritage. Struck by the sheer labor evident in these carefully composited cross-stitches, arrangements of glass tiles and deliberately organized colors, texts and symbols, it’s clear Nassar’s practice is propelled by equal parts resistance and longing. Works like Al-Atlal (The Ruins) (2024), where animals find a hieratic home in formal quadrants against a backdrop of mountains and water, is how Palestinian motifs become deeds of recollection. The act of tiling and embroidering are a means of resistance against the erasure of memory, both of traditional practices and an ontological experience rooted in what Nassar can imagine and study of his origins. Simultaneously, the act of each work embodies a sense of yearning, where all of his exerted industriousness brings the artist closer to where and who he wishes to be near. At the core of Nassar’s practice lies the profound sense of tangibility, dedication and patience which reveal to us what he hopes to keep alive. His work not only reveals who he is and what he desires but also aims to evoke, for himself and others, the distinctive space between memory and experience, reflection and an immediately familiar and cherished world, of being Palestinian and of not being in Palestine. Through the labor-intensive processes of weaving and tiling, Nassar encapsulates a sense of home and identity that defiantly resists the dislocation wrought by diaspora.

Anat Ebgi

4859 Fountain Ave.

Los Angeles, CA

On view through July 20, 2024 -

PICK OF THE WEEK: Rhea Dillon

Soft Opening at Paul SotoThere’s no trick of the moonlight at Rhea Dillon’s show, “Gestural Poetics.” Inside and out, each work happens twice. Dillon’s drawings, nestled in sapele mahogany boxes within the white cube gallery, enact two histories at once. While the moniker “sapele” hails from a Nigerian city, the hardwood was once used to build slave ships, consequently disrupting how to read Dillon’s works against the supposedly neutral space of a gallery. Inset in boxes propped against the walls, her oil-stick drawings of spades emerge in clamorous flesh tones or occasional bursts of yellow or purple. If this exhibition intends to release the recognition of Blackness from an object or commodity and lean into Blackness as a natural form of abstraction, the entirety of the show is clever, verve and precise. Dillon’s sensitivity to Black hyper-visibility recovers a sense of amorphicity for Blackness through reconfiguring canons of representation. In probing questions about this long crisis of recognition and addressability, an intimate relationship between imaging, the world and “the way things are,” I came to the contradictory question: Is it wonderful that she has created these works or should I be outraged that the world is this sinister?

Paul Soto

2271 W. Washington Blvd.

Los Angeles, CA

On view through June 1, 2024 -

From the Editor

May/June Volume 18, issue 5 Dear Reader,

Dear Reader,In the early Artillery days, I assigned a writer to critique the films and videos that were showing in the sprawling 2007 MOCA exhibition, “WACK!: Art and the Feminist Revolution.” There were more than 20 films and videos included, mostly viewed on the original, portable black-and-white television sets or small analog monitors with bulky VHS recorders and other archaic equipment. Thick black cords, oversized headphones and extraneous hardware gadgets were in full view, making them part of the dated presentations.

After seeing the massively impressive, exhaustive exhibition (full disclosure: I pretty much skipped over the videos), it dawned on me that I should return and really watch the videos, all of them, in their entirety. The low-budget (or nearly no-budget) production of most of the work provided a window into the then newly discovered medium being used in art—video.

Besides my desire to go back, I thought that others might feel the same way. (Don’t most museumgoers skip watching the entire films at big exhibition shows?) I found myself drawn to the crude videos with the grainy black-and-white closeups of women’s faces and naked body parts—usually the artists themselves—always full-frame. Contemplative observations, confessions, questions, concerns and self-absorption seemed to be a running theme in a lot of the films. But really, could I sit through all of them? Perhaps I should’ve included a rating system when giving the writer his assignment to cover the show.

There doesn’t seem to be much need for help in making those decisions these days. In this Film, Animation & Video issue, we feature six female artists that make it impossible to walk away from their moving image pieces. For one thing, it’s usually the main thing in the exhibition, filling the gallery entirely, not tucked away in a darkened side room. Technology has leaped into a big fast-forward since the days of the “WACK!” show. Although Palestinian artists Basel Abbas and Ruanne Abou-Rahme draw on the past for inspiration, their multichannel, multisensory films look very different from the days of the portable black-and-white TVs. But they still talk about the things that are important to them, whether personal, familial, political or emotional, as reported by writer Tara Anne Dalbow. Admittedly, there are new matters to explore 20 years later. For instance, multidisciplinary artist Ethel Lilienfeld delves into 21st-century concerns, such as “self-image and the filters that augment—or completely change—our appearances,” writes New York contributor Annabel Keenan. Lilienfeld explores our virtual selves, or rather how we present ourselves in the virtual world. Women especially fall victim to the superficiality of social media, even to the point of going to plastic surgeons with their “filtered” double as a model.

In the end, the writer finally turned in his copy on the “WACK!” show, claiming he did as well as one could in the three hours he spent watching the videos and films. He came up with a rating system, and one of the films he watched in its entirety—and claimed to have been “mesmerized” by—was 27 minutes long. Our contemporary tools make the art of creating moving images a much easier process. But the message remains the same, as you will see in these pages.

-

Brad Kronz

Gaylord ApartmentsFor his untitled exhibition at Gaylord Apartments, Brad Kronz created what looked like a kind of deinstallation—the last few items left in an apartment before moving out, things you don’t know whether to leave or to stack on top of an already packed car: an auxiliary chair, a few Wi-Fi routers and wires, scraps of defunct wood furniture. But upon closer inspection the objects had each been carefully placed, some altered by the artist.

The wall works on view, several of which looked like finished wood floors or tabletops, left the viewer with an opaque surface where there should have been something to look into: a mirror, a window or a painting. Instead, a smoothed wooden surface on top of a layer of drywall conceals matter sandwiched between them. Around the edges of both Designer of the cross and Fake spirituality filled with darkness (all works 2024), something pokes out where insulation might be. In the former, it’s wool that looks like human hair; in the latter, a thick black cord is wound around the work’s interior. Kronz addresses a gap we don’t often see but only sense beneath the surfaces that surround us.

Bradley Kronz, My car lives outside, 2024. Image: Brad Kronz courtesy of Gaylord Fine Arts. Floating in the middle of the room was a similar-looking piece, Lives in NY, Works in Cincinnati, a wood support and drywall surface with wool in the middle. But with this work there was something to look into. Mounted where a peephole might be is a sepia-faded photo of an open door. The work has a wire on its back as if it’s intended to be mounted on the wall. Kronz creates an infinity effect with these sculptures but with the end result of opacity rather than clarity. A door within a door, a wall on a wall; the viewer’s perspective hits a limit.

In the short text he wrote to accompany the show, Kronz offers a Duchampian philosophy: art offers to “resolve,” as he writes, the implicit problem posed by objects, suggesting that once it is art, “the object is never again your problem.” In making art with or about these random objects, Kronz develops a way to deal with their adjunct presence. The work that addresses this most directly is My car lives outside, a sculpture made of the bottom half of a stool turned upside down, its inverted legs supporting two pieces of bluntly cut wood that display two Wi-Fi routers with cords coiled in the space underneath. This is the most frustrating work in the show but perhaps the most evocative. It has a pesky stupidity—both as an inane subject for art and then in the impotency of its unplugged cords, which render it useless while leaving us to deal with its bluntly dull appearance. But Kronz doesn’t fuss too much over it, or push this imperative to find “poetry in the mundane.” In fact, he asks us to sit with the prosaic, the objects that may, in fact, be just objects—or art, which perhaps too, is sometimes just boring.

-

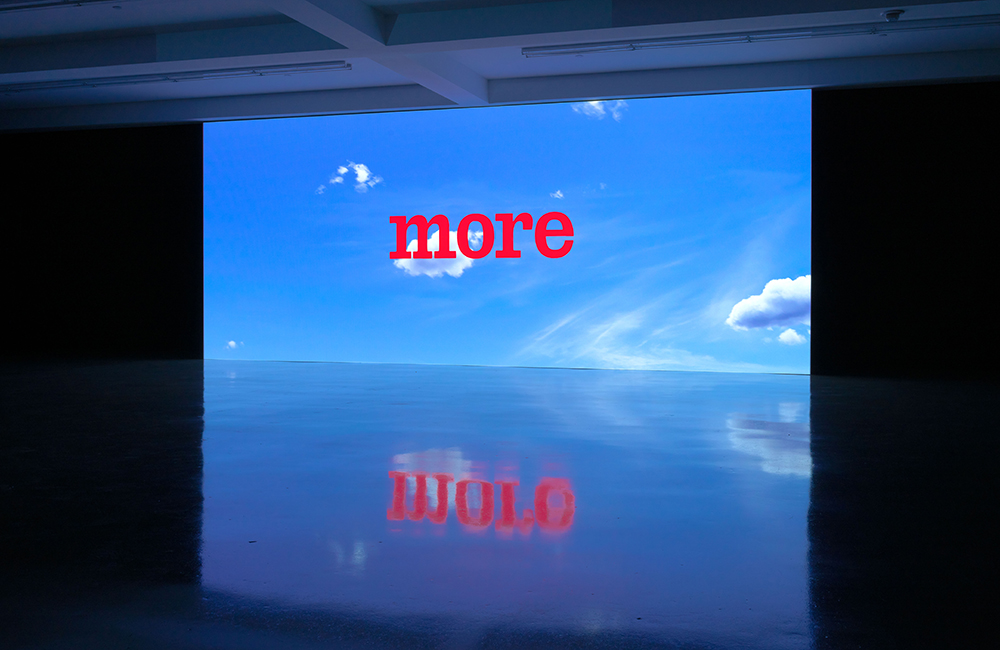

Nora Turato

Sprüth Magers“Self is source. Self is pure positive energy. Self is worthy. Self is full of vitality. Self is healthy. Self is eager about life. Self is amazing.” One might imagine this incantation spoken in a low, meditative tone, as though by uttering the words with enough intention the speaker might manifest this vision in their own life. But artist Nora Turato chirps the staccato affirmations quickly, her cadence upbeat, like that of a motivational speaker selling you on tools to transform you—finally—into someone who can “get to [their] ultimate destiny.”

Critically, that destiny and those tools are never disclosed in Turato’s 47-minute video pool 6 (all works 2024), which occupied one half of the two-room exhibition “it’s not true!!! stop lying!” at Sprüth Magers. Instead, she sutures plaintive cries for healing, hackneyed wellness jargon and interrogations of selfhood into a sweeping monologue, which was present both as large red subtitles and as audio, her caricatured voice booming throughout the space.

Like pool 6, Turato’s text-based enamel wall works and murals distill an affective mode prevalent in recent years: that of the wellness aspirant. One enamel-on-steel work reads in blocky red lettering “I NEED SOME HEALING.” Another wall-spanning piece reads “speaking my TRUTH!!!” Each is composed solely of text on a monochromatic ground, employing scale and capitalization to register a frantic tone. Much of Turato’s text sounds confessional, but the phrases appear without context, like floating signifiers awaiting a subject to adhere to.

Nora Turato, pool 6, 2024. Photo: Robert Wedemeyer. © Nora Turato. Courtesy of the artist, LambdaLambdaLambda, Galerie Gregor Staiger and Sprüth Magers. Such anxieties about authenticity, healthfulness and personal achievement channel the market consciousness of a $5.6 trillion wellness industry. The artist appropriated her text from films, online forums, motivational talks and ad copy. Turato arranged the resulting pool of language in a book, which she then edited into monologues for her videos and performances, enamel panels and murals. Rather than offering viewers a glimpse into the private consciousness of another, she ventriloquizes the afflictions and affirmations that structure the wellness market’s faddish vocabulary.

Turato’s anti-lyricism is furthered by the works’ industrial aesthetic. Made of steel, vitreous enamel and emulsion paint on sometimes billboard-level scales, Turato’s works are not intimate, despite their emotional tenor. Instead, they suggest that the language of self-optimization pushes in on us by way of contemporary marketing strategies, infiltrating not only our speech but our innermost feelings as well.

One might feel superior to the anxious desperation voiced by the more plaintive of these works. Others are ironic and detached in tone, such as authenticity haha, in which the titular words emblazoned large-scale walls at the gallery’s entrance as if inviting viewers in on a joke. And in pool 6, Turato’s magnificent performance at times can seem spiteful. But at the same time, as she estranges and thus critiques the idioms of an industry profiting from personal and social ailments, she mirrors some of its allure. Backgrounding the text in pool 6, clouds move in real time through a pale blue sky. Viewers were drawn into the video’s atmosphere, its heavenly image mirrored by the shiny floor below as though beckoning interlopers to enter its space. Once you’re in, it’s hard to exit.

-

Se Oh

Stroll GardenAs a Korean-born queer person who was adopted at nine months by a conservative white Christian family in the Tennessee Bible Belt, Se Oh struggled for years with the trauma of rejection, including from their adoptive parents who believed that homosexuals don’t make it into heaven. In the two-part exhibition “Elegies (Little Deaths/The Witnesses),” Oh enacted a symbolic purging of painful memories and the emotional wounds they suffered simply for being Asian American and gay, while paving a road to self-affirmation.

Part I of the exhibition consisted primarily of “Little Deaths” (2024), a wall-mounted installation of 60 small, handmade porcelain vessels. Arranged on a grid of shelves, these are loosely based on Korean funerary objects that are traditionally buried with the dead. Stylistically, the vessels simulate forms found in nature, with their mouths opening like flowers. Metaphorically, the overall grouping was intended to represent the unpleasant or regrettable experiences, habits or relationships that punctuate our lives, and that, through will and resilience, we are able to put behind us. Oh also suspended two clusters of vessels from the ceiling, titled A Mother’s Tears and A Father’s Tears, (both works 2023) as representations of their own parents’ grief.

At the opening reception for Part I, Oh invited visitors to participate in a ceremonial catharsis through which they too could lay some bad recollection to rest. Each attendee was asked to write their memory on a piece of incense paper soaked in essence of chrysanthemum, a flower associated with Korean funeral rites. The papers were then lit and burned in a ceramic vessel. Oh’s participatory healing ritual is similar in process and format to Kim Abeles’ Pearls of Wisdom: End the Violence project (2011), in which the artist led workshops for victims of domestic abuse and their supporters, who each wrote traumatic memories on pieces of paper that they concealed in oyster-shaped sculptures they made themselves.

Se Oh, “Barachiel,” 2024, high fire porcelain and celadon glaze. More than a month into the exhibition, Oh added Part II, “The Witnesses,” (2024) a series of new, larger vessels based on Old Testament depictions of angels. While still mimicking floral or vegetal formations, these symbolic observers of the artist’s “Little Deaths” have eyes peering out from them. Additionally, they have been coated with celadon, a green-tinted glaze that originated in China and is common in Korean ceramics. In wedding Judeo-Christian subject matter with a medium tied to their ethnicity, Oh cleverly unites their birth and acquired heritages.

The second half of the show also included a number of newly created vessels that focus on rebirth and rejuvenation. Conceptually, this idea was expressed through recycling the ashes from the earlier ceremony. For added hanging works such as Ego Death (2024), the artist mixed the ashes into the celadon glaze, giving them a new life and context. This technique was also used for the interior sections of new “nested vessels,” where one ceramic object is lodged inside another. The artist views the exterior vessels as flowers that open to reveal one’s inner self. While presenting us with a delicate and poignant form of visual poetry, Oh appears to have found a path to acceptance and peace.

Dear Reader,

Dear Reader,