While most people half his age are searching for their car keys, Wayne Thiebaud, now 93, peppers conversations with literary references and recalls in vivid, sensual detail the coat that Hans Hoffman wore at an art reception 50 years ago—“it was so thick that it looked like pressed horse manure; it was about that color.” Thiebaud’s memory represents an encyclopedic knowledge of the history of painting, and a firsthand memory of much of 20th-century America.

Many contemporary painters rely upon photographs for reference; Thiebaud paints solely from memory. Some writers have described his memory as being “photographic,” which always struck me as a misnomer: a photograph is a single frozen optical moment, a human memory is fluid and full of sensory information and nuance.

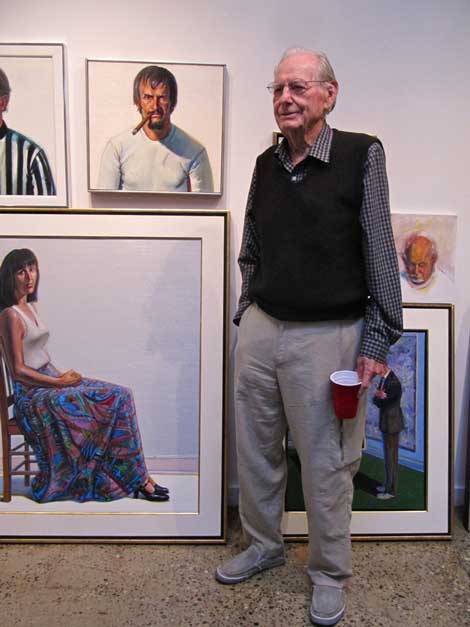

This spring the Laguna Art Museum hosts a survey exhibition of Thiebaud’s paintings, drawings and prints, self-selected and titled “Wayne Thiebaud: American Memories.” I recently paid a visit to talk to him about his work and life on the occasion of his exhibition. Full disclosure: I worked closely with Thiebaud as a student and teaching assistant at the University of California, Davis.

In conjunction with one of the longest and most consistently successful careers in American art, Thiebaud was a full-time professor at U.C. Davis for over 50 years. Thiebaud, the teacher and person, is a lot like his paintings: simultaneously down to earth and sophisticated; folksy and yet formally composed; sometimes reserved or even austere, but truly full of humor and a warm humanism that is somehow distinctly and quintessentially American. Thiebaud paints every day (no assistants), plays tennis twice a week, maintains an active national exhibition schedule and continues to push his work into new territory. Last fall in San Francisco, he had a show of 47 paintings of mountains, all done from memory and invention, three-quarters of them painted within the past couple of years.STUDIO VISIT

On a rainy Saturday morning in February, I knocked on the back door of the unmarked gray warehouse building in Sacramento where Thiebaud works. He opened the door and led me into his studio, a modest but comfortably-sized white room with a dark carpeted floor and a skylight overhead. In addition to brushes, paints and palettes, his studio is full of objects: African sculpture, a stack of cigar boxes, photographs of his late son, Paul, a wall of children’s drawings and notes from his grandchildren. Then there are paintings and drawings: his own, some by friends and a framed Matisse self-portrait line drawing with a wry and crooked smile.

As he was trying to sell cartoons and become an advertising art director, he fell in love with painting. “The painters I began to be really interested in and admire were the Abstract Expressionists,” he says. In 1956 he decided to move to New York to meet his “heroes” once and for all. He was struck by the fact that even though many of them were originally from Europe, “all of them were trying to be Americans.” Thiebaud befriended many of them, eventually becoming close with Willem and Elaine de Kooning as well as Franz Kline.

Like most serious painters at the time, he tried aping the styles of the Abstract Expressionists. But ultimately, Thiebaud says, he realized that he “had no idea what ‘art’ was,” but “was really interested in painting.” The painters in New York that he respected talked a lot about being authentic and finding something that was personally meaningful. That idea led directly to his mature paintings of popular American foods and products beginning in the 1960s. By then he had made several trips back and forth across the country and had noticed that even as states and regions changed, he would always see the same slice of pie with the same kind of presentation. In searching for a subject matter that he felt he knew something about—something concrete—he drew on his memory of these ubiquitous foods he had seen.

A STAR IS BORNIt is easy to forget how radical it was in 1962, when gestural abstraction still reigned supreme, to present deadpan paintings of pies and cakes and gumball machines in a serious uptown New York gallery. The show, at the Allan Stone Gallery, was an unexpected sensation. The paintings all sold and the press was calling: Time and Life magazines, and more, wanted to interview him. At 41, the professor from California was an unlikely and sudden star. He admits to being shocked by this response from the famously tough New York art world. And when the dust settled, he found himself back in Sacramento standing in front of a blank canvas. He was “absolutely panicking,” he tells me. “Is this something that really occurs to you? And what—now what am I going to paint?” The phenomenal success and attention of that debut exhibition in New York presented him with daunting expectations and pressure. The normally grounded and conventional Thiebaud had stumbled into the unexpected role of iconoclast.

But what looked avant-garde then can now be understood in context: Thiebaud did not share the ironic distance of the other artists who became known as “Pop”—he may instead be, as the New Yorker writer Adam Gopnik dubbed him: “The Last Honest Painter.” Thiebaud has always resisted the Pop Art label, expressing an affinity with painters like Chardin and Morandi rather than Warhol and the rest.

He always kept his distance from New York, teaching in California and living a studio life insulated from the daily noise of the art world. He focused on his personal, rigorous and relatively traditional dialogue with painting.

And yet, there are rich ironies that have come with his lifelong pursuit: The more traditional and honest Thiebaud tries to be, the more radical his work becomes. In this age of ever-shortening attention spans, he shows us a complex kind of long looking. In his later series of “Cities and Landscapes,” especially, Thiebaud orchestrates a kind of anthology of seeing: glimpses, glances, infinite perceptual observation, and long-held memories, things seen up-close, from far away, from above, from below, frontally presented and from every conceivable kind of point of view and perspective—all within a single painting. Art writer Jed Perl has formulated that the very best artists of the Modern era are simultaneously radicals and traditionalists; Thiebaud fits that description as well as any artist I can think of. His achievement is not that he fit into a particular movement, but that he remained so impossible to categorize. He combines a certain “Pop” sensibility with realism, abstraction, impressionism, cubism, cartooning, sign painting, and too many other influences to list. The result is an idiosyncratic American gumbo of a style uniquely his own.

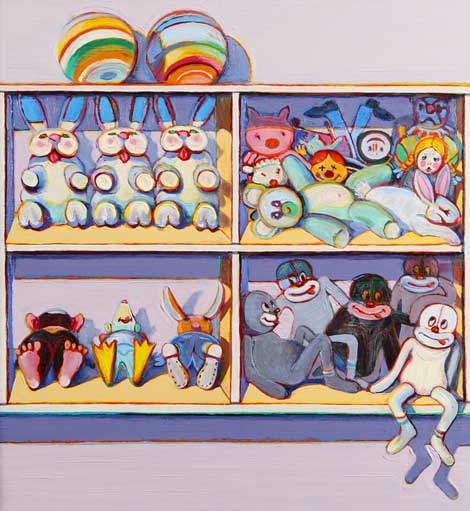

IN LIVING COLOROne of the most identifiable elements of Thiebaud’s work is his distinctive use of color. In Thiebaud’s world, shadows can be electric blue; fields of crops can be bright orange, pink and lime green. The magic trick is that he is so blatant with these chromatic conceits, and yet somehow makes us believe that the paintings represent some kind of “realism.” Thiebaud’s use of color is one way of understanding what is, for me, perhaps the most compelling aspect of his work: how aggressively he risks failure and courts disaster. A casual observer of his work might mistake his crowd-pleasing candy colors and accessible subject matter as seemingly safe choices. But spend some time with the work and that assumption gets turned on its head. He could easily have sidestepped the cliché genres of still life, landscape, and figures. Yet he proceeds, fearlessly or foolishly, with a courageous appetite for a challenge.

“Nostalgia” is a nasty word in Modern Art, but Thiebaud says he is unafraid of it, “I am sure it’s there with me. I mean, I am nostalgic about a candy counter when I worked as an usher at the Rivoli Theatre.” He points to a painting of a candy counter on his easel. “It’s just so interesting to paint, ya know? It’s just so much fun to paint the light and try to get the space to work in a way which I’ve never quite gotten.”

He says this desire to court disaster was something that de Kooning and friends spoke about regularly—Diebenkorn called them “anomalies”—the abstract painter’s strategy of purposefully introducing something that would disrupt and threaten the cohesion of a painting.

Thiebaud’s paintings present a charmed world—the result of a charmed life; a “golden boy” living in “the golden state” during the golden age of the postwar American economic boom. Knowing that the art world often rewards darkness and cynicism, and mistakes a sense of humor for a lack of seriousness, I ask him if he has ever received criticism for his paintings being too cheerful? He responds with “Yeah, oh yeah. Over all, I am surprised I don’t get more of it. But what they usually say is, ‘Don’t believe his cheerfulness.’” He says that critics have preferred to see his work as “basically heavy-spirited.” I ask him if he agrees with that interpretation, and he puts it simply: “No.”

At a time when various forms of Minimalism ruled the art world, Thiebaud created his own idiosyncratic language of Maximalism—maximum color, maximum light, maximum materiality. His paintings don’t just represent the bounty of postwar America, but create their own internal condition of bountifulness, richness, and variety. His paintings project an almost obscene pleasure in paint and color: oil paint becomes whipped cream and frosting, substances ooze and spread across the surface with comical verve. His paintings are known to make people laugh and smile when encountering them, partly because of the subject matter, but I suspect that effect is equally a reflex prodded by the blatant sensuality of the work. With Thiebaud there is also an implied populism—the universally accessible subject matter, the crowd-pleasing color and texture, the references to folk art and the American vernacular. I ask him about this pleasure principle and he chimes in quickly: “I mean, why not buy into the whole idea of Epicureanism? Why do we have to punish people?”Because his sense of memory is so developed and nuanced, and because of his command of drawing and painting, he has made his memories into physical facts that exist in the material present. Thiebaud’s memory, that is to say his paintings, will likely long outlive the time and place which produced them. Future generations, when they want to learn about what this “America” place was like, will look to Thiebaud’s work.

“Wayne Thiebaud: American Memories” runs through June 1, 2014, at Laguna Art Museum, for info www.lagunaartmuseum.org