Your cart is currently empty!

Adam Katseff

Throughout our evolution we’ve been afraid of the dark. As creatures primarily endowed with encephalic gifts, we aren’t well-equipped to vie with nocturnal animals, full of tooth and claw and with more finely attuned senses. They make quick work of us when we don’t see them coming. Darkness holds for us a sense of foreboding; in the dark we deliberately slow our breathing to hear what in the world is happening around us. Even in our aggressive modes: hunting and exploring, we quiet ourselves in the dark, peer into mystery, trying to make out the meaningful forms on the horizon.

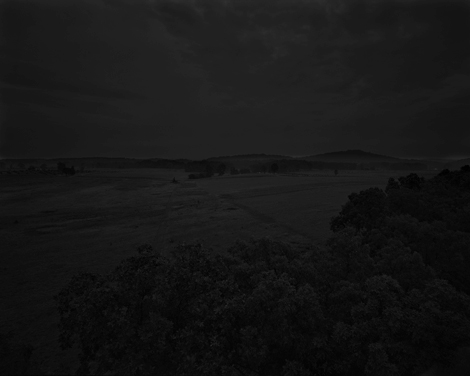

Adam Katseff’s work, “In the Course of Time,” at Sasha Wolf Gallery stands out from the crop of contemporary photography in New York galleries by presenting staggeringly beautiful nocturnal landscapes of lacquered shadow that are unironically mysterious. Method and content come together to make them so. A meditative, patient eye is required to gather these images—Katseff sets up his camera at night with the shutter wide open so the film can siphon up errant light from the moon and stars, before the dawn intervenes. The images require a meditative approach to perceive them as well. Shapes are initially hard to decipher. One’s eyes adjust and then lakes appear, made into smoky seamless marble, valleys morph into passages to the underworld, and snow-capped trees become circumspect honor guards (the “Night Landscapes” series, 2012-13). Katseff’s work is well and truly liminal: astride the border between the now and the ancient, the visible and the clandestine, the pedestrian and the mythic. We become acquainted with the night, looking at these landscapes. We learn patience, waiting for the Fairie to appear.

The works in the “Flames” series (2010) aestheticize another of the primeval elements, in addition to earth and water. In these images fire appears to pour itself over the object, inhabit it, ravage it rather than simply consume it. Though these photographs are not as mesmerizing as the landscapes, they may make a viewer want to discount scientific accounts of fire as excitation of molecules in favor of more animistic explanations—possession, for example. The “Whole Night” series (2011) on the other hand demystifies the night sky, making it a kind of clever designer-wallpaper with stars leaving lighter traces of their passage in a graphic rather than organic style.

Katseff’s use of a black-and-white palette makes him very much a part of the history of fine art landscape photography following those like Edward Weston, Minor White and Ansel Adams. The attention to formal qualities is made more evident in his “Interiors” series (2012-13) where Katseff shows us model homes that are the opposite of the dark we left: simplified, defoliated, flooded with light, so that no corner allows for hiding. All is visible and known. But where Katseff’s work is most compelling is in its sense of not knowing what is up ahead, therefore causing us to scout the landscape with our senses on guard, fully alert.

Comments

One response to “Adam Katseff”