Ornately grotesque, Aaron Johnson’s paintings, on display at Stux & Haller Gallery, are vibrant, densely packed expositions on sex and death. According to Johnson the effect he’s after is the erotic intensity of two bodies merging together and two individual identities melding into one. “It’s an emotional, beautiful thing that’s also corrupt and falling apart,” he says in an interview I had with him back in January.

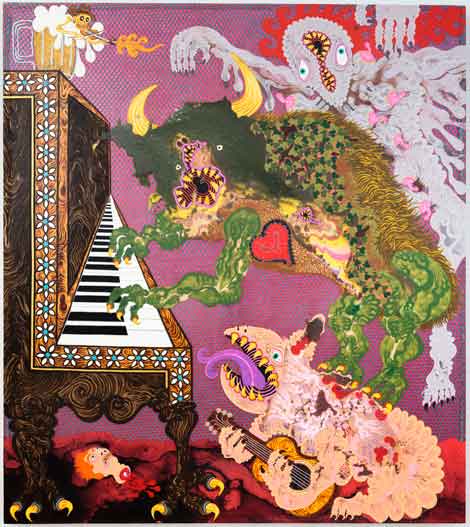

Sexual climax as death is hardly a new idea, but it’s never been done quite like it is in Johnson’s Heart Beat (2015), an eye-popper of a painting, which depicts the moment of ejaculation as a flesh-melting, electric apotheosis.

The work is one of Johnson’s “reverse painted acrylic polymer peel” paintings created in a multi-step process. Each painting has three layers of paint separated by a layer of acrylic polymer that’s poured onto the finished layer of pigment and left overnight to harden. The layering adds depth, luminosity and dimension to Johnson’s work.

To make things even more complicated, the painting is done in reverse. Johnson puts down the detail first—fangs, eyes, talons, etc. A coat of color is applied next, which completes the figures. Finally, the background layer is added. To grasp how hard this is, you have to understand that from the working side, it’s impossible to tell what the painting looks like; it has to be turned around in order to see its true appearance.

“The way I paint is the opposite of how most painters work,” Johnson explains. “They start with broad strokes and start to find forms and then refine and approach details. I start with detail and zoom out. It’s like the details are super precise and controlled and I know what I’m going for. In the beginning, I’m using a tiny brush; it’s painstakingly slow and then as the paintings progress, I’m relinquishing control of this thing I labored on. The backgrounds often involve splatters and poured paint—chance things and a little bit of chaos I welcome the mistakes that happen. They’re all part of the overall explosion of stuff. So I’m not exactly quite sure what the finished work is going to look like from the front anymore.”

After all the paint and acrylic polymer is layered onto the stretched polyethylene plastic sheeting Johnson uses as his painting surface, he removes it and transfers it onto plastic netting. This is done by laying the painting surface flat, plastic side down, and pouring a final coat of polymer and then applying the netting. The polymer saturates the net, congealing all those layers of paint to it as the polymer dries creating a glass like surface, at which point, the polyethylene sheeting is peeled away.

Johnson began using netting because when he attempted adhering the paintings to canvas, it wasn’t porous enough to accommodate the layers of medium and he ended up with a lot of air bubbles. He got the idea to use the more unconventional material walking past a construction site in New York City where he spotted the familiar orange net barricades. Eventually, he found a company in Connecticut that manufactures every kind of netting imaginable. Johnson even did a commission for them using all the different kinds of netting they produce. They now send him barrels full of the stuff.

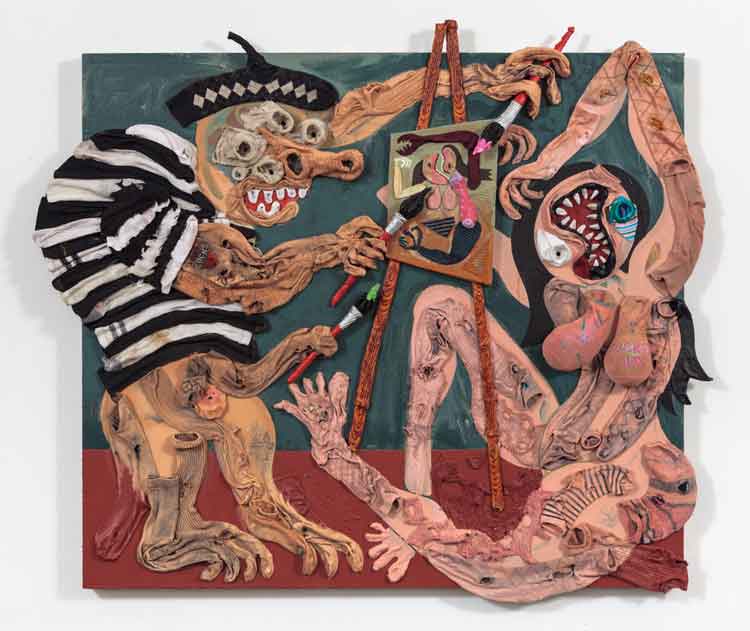

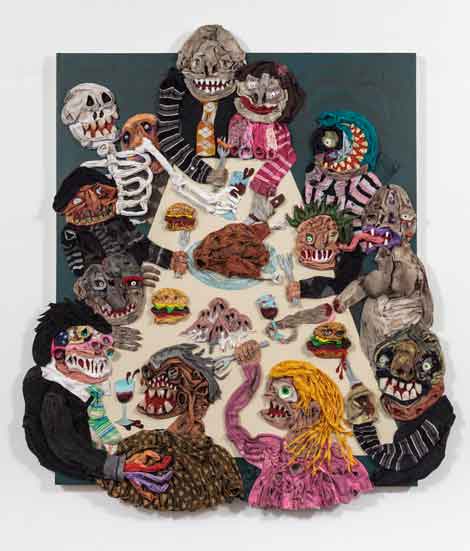

Made from used and donated socks collected from Johnson’s social media followers, his sock paintings, also on view in the exhibition, are nearly the exact opposite of the sleek peel paintings, having a 3D collage-like effect that turn them essentially into bas-reliefs. Making them must be liberating after the precision and methodology required with the reverse peel technique. The socks are such an offbeat, low-tech material, calling to mind all sorts of reference points from dirty laundry to Lamb Chop to Arte Povera. They’re also weirdly powerful. Endowed with their own meaning as socks, they also have a distinctly anatomical quality with their orifice-like openings and phallic shapes. Painted flesh color, they resemble skin.

Johnson “knows from” composition and how to fill up the picture plane with dynamic form. One admires the overall pattern of each work even before one takes in the image. This is the case with Heart Beat (2015) and also with Johnson’s irreverent and amusing homage to Picasso: Pisocko (2014). How perfect that Picasso not only has five eyes, but his penis is holding one of the brushes, and certainly doing most of the painting.

I like the way The Piano (2014) combines two very different approaches: the carefully rendered piano with its wonderfully archaic trompe l’oeil wood grain and Mughal flower motif, with the looser mishmash of paint and pattern that comprises the minotaur-like creature and his ghoulish companions. It’s all set against a unifying geometric OpArt backdrop created by the pattern of the netting.

In Beast Feast (2014), Johnson uses socks to create a work with the compositional and monumental attributes of an Old Master painting neatly juxtaposing the insignificant with the important. His quite goofy figures are reminiscent of old-fashioned sock puppets, but they have an earthy fierceness that’s hard to dismiss. They’re both repellant and transfixing.

Johnson enjoys inserting “little things for people to discover” in his paintings like the woman in Southern Gothic (2015) whose tears are turning to ghosts as they float up to the sky. He uses a lot of food imagery. Often, it’s fast food utilized as a jab directed at American capitalist culture. Sometimes it’s just a prop, other times it takes on a more active role such as the container of fries copulating with a burger.

And there are plenty of musical instruments, a favorite subject of painters since time immemorial. Johnson says it’s because he really likes music, but I wonder if he, like so many before him, is tapping into a more expansive meaning.

Johnson grew up surrounded by Indian art, a legacy of his mother’s ex-pat upbringing. He says the aesthetic is so ingrained in his self-conscious he references it without thinking about it. This explains the ease with which he incorporates the verging-on-garish palette and the marvelously inventive patterns and flame-like gestures that recall Indian miniatures and enliven his paintings. In some works, Johnson makes more direct reference: inserting the elephant footstool he inherited from his grandfather in one, a Ganesh-like figure in another.

Another potent influence is the Mexican Day of the Dead; Johnson has appropriated its skeleton figures to populate his work. He shares the attitude of laughing at death and an acceptance of its tandem position to life.

There’s plenty of blood and grossness in Johnson’s work, but it’s handled in such an irreverent and intentionally outlandish way, it comes across as darkly funny rather than truly disturbing.

What’s really important here is Johnson’s innovative technique and inventive narratives that bring remarkable freshness and vitality to his paintings.

AARON JOHNSON

PISOCKOPHILIA

New Paintings

February 18 – March 21, 2015

Stux and Haller Gallery

24 W 57th Street, New York

http://www.aaronjohnsonart.com/