Your cart is currently empty!

Month: March 2015

-

‘That Transparency Thing’ – Blob to Blot, Part II – A Debate Over the New LACMA

[Part I of this post appeared yesterday, following the preceding evening’s Third Los Angeles forum at Occidental College. I continue where I left off – as LACMA’s Director, Michael Govan left the stage to the evening’s host, the forum’s principal organizer, and Los Angeles Times architecture critic, Christopher Hawthorne, and his panel – Alan Hess, Greg Goldin, Mark Lee and Sharon Johnston (of Johnston-Marklee), and Hawthorne’s L.A. Times colleague, Carolina Miranda.]There was something slightly awkward about this transition – as if an appellant advocate had made his argument, and the case handed over to a panel of judges to arbitrate or come to some definitive decision. It was a difficult case to argue and a difficult decision to make; and if the panel ultimately did come to some consensus, it was not exactly what we would call a clean precedent.

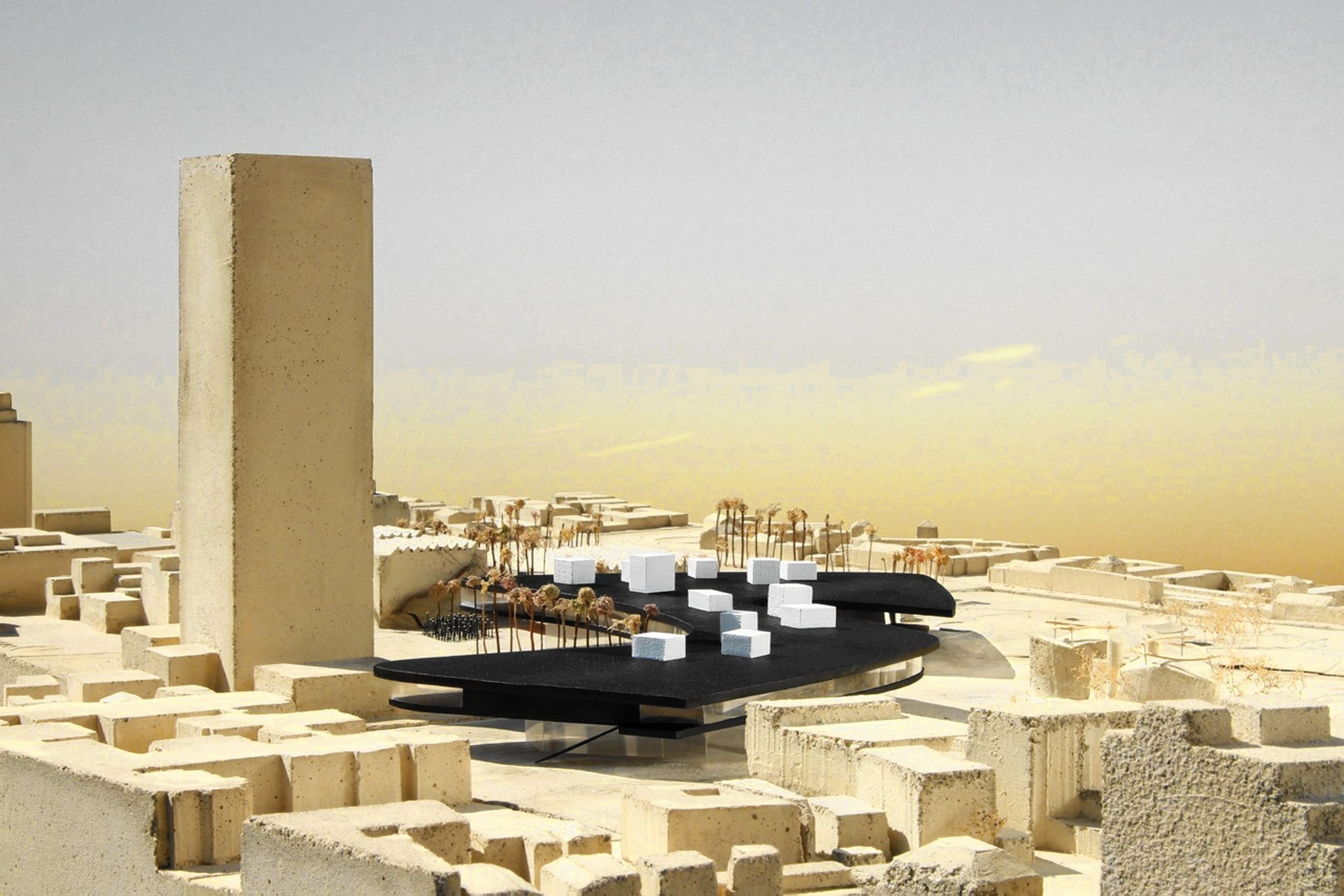

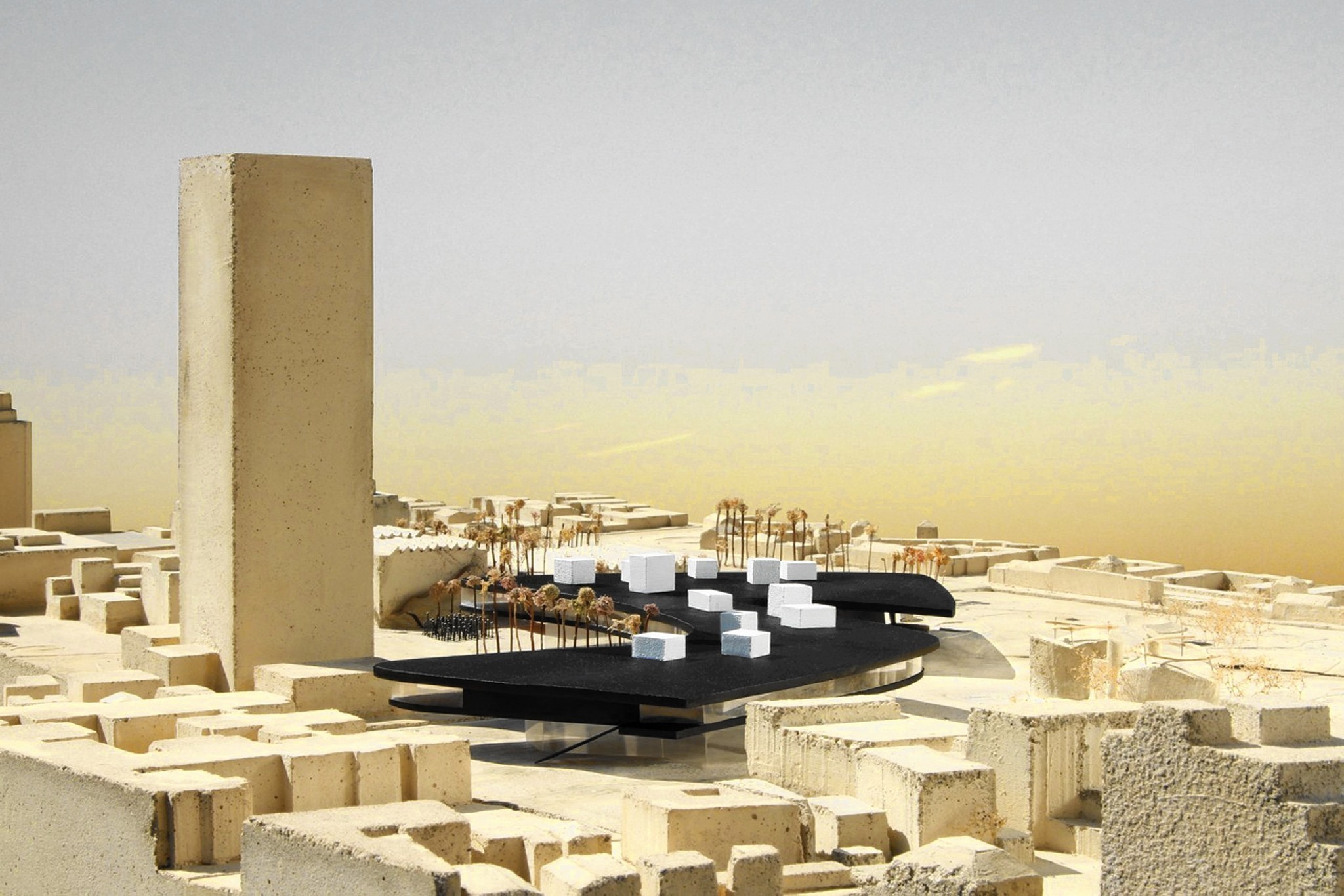

Govan had to defend what amounted to a quartet of contradictory positions. On one hand, he had to stand by the original design he’d gotten everyone worked up over to the tune of about $300 million. On the other, he had to defend the position that the changes made, though necessary and an improvement, had not fundamentally altered the original concept and silhouette for the building and site. Without going into detail about the alterations (which in any case are mostly covered in Hawthorne’s coverage), this is partially true and partially false. Although the altered silhouette has lost some of the spirit and sensuality of the original design, it is in some ways more coherent, the massing more equally (and gracefully) distributed to the north and south across Wilshire Boulevard.

The issue of ‘transparency’ was always a bit fraught, regardless of Govan, et al.’s initial hype, and for that matter regardless of hypothetical views into the galleries and perspectives onto the exterior; and Govan didn’t come close to making the case for it here. More problematic was the issue of the entrances, which were originally suppose to move visitors through the cylindrical glass columns or plinths, past storage racks of art, which would be at least partially visible to those outside. There were always issues with respect to access, preservation, movement/traffic and attendant structural stresses. But now the access points would be both reduced and more distantly placed. (And where exactly? And by what? That dreaded (by Govan, anyway) staircase? Zumthor and Govan appear not to have worked this out exactly.)

The axial shift of the museum’s Gumby-like footprint southward across Wilshire Boulevard could only strengthen the case for the elevation of the structure. But almost all the panelists expressed some concern for the (off-Wilshire) public space beneath the structure. The very fact that it would share the tunnel/channel it would create over Wilshire sets us up for a slightly darker – and less park-like experience than what might be expected or desired for a museum sited in what is, after all, a park; doubly ironic given that the Zumthor plan (in theory) returns two-plus acres to the Park.

That is to say, Hancock Park, whose original land concessions to the Museum, according to Greg Goldin, had been continually breached in its various expansions. In theory, the space would come in for much the same use as the Times Court between the Bing, Anderson, and Ahmanson buildings on the current campus. But, as Carolina Miranda, among others, suggested, the effect might seem a bit like hanging out under a freeway overpass. (Hawthorne noted that there were critics who saw the freeways as among L.A.’s greatest and most emblematic stuctures.) Not a big issue, assuming the light and space (and Park) only a few hundred feet away; but again, given the closure of those glass cylindrical supports, not exactly contributing to ‘transparency.’

Where Govan was most directly challenged (though not necessarily by the panelists individually) was the obvious (and clearly practical) shift from the flattened plot of galleries that filled the museum floor plan almost to its perimeter to a sectioned plan that gave some of the galleries double (and, from the appearance of some of the renderings, even triple or more) height. Govan’s original mandate had been for an aggressively flat, unbroken horizontal line; and Zumthor’s revised rendering had clearly breached that. There were no interior renderings to give an idea of the effect from inside the galleries, but the exterior effect was less than elegant. More to the point, the elevation no longer presented that unbroken horizontal line. Govan was insistent on a single storey museum that now had a dozen two- or even three-storey spaces. (I sort of wondered if this was the new de facto growth plan: just keep punching holes in the roof as needed.) Govan’s position now seemed all but absurd. My own guess is that this is a baseline cost issue. A second floor, however raw or partially finished, may add just enough expense to push the cost to a level the County Supervisors or certain Board members may find unacceptable.

Here’s the thing: the museum experience (as Alexandra Lange observed so eloquently) is not like other gallery, cultural or public/commercial/retail experiences. It is a place to muse, to wander, to browse speculatively. We’re not there to acquire or even experience something specific. There’s a certain randomness to the encounter, apprehending, observation that takes place in this setting. Alternatively, we’re there to look at something completely specific. Nothing is going to deter me from moving up to a second, fourth, or fiftieth floor, to see the exhibition I’ve come to see. (I was not so long ago on the 4th level of BCAM. Mr. Govan should be assured this was not a problem. This was a pleasure.) For that matter, I don’t buy it as commercial/retail psychology, either. If I’m at Barneys or Saks to look at Alaïa or Rick Owens, I’ll climb the stairs to get to whatever I’m shopping for. And then there are these things called elevators….

Alan Hess, an architect and Pereira scholar (he contributed to the anthology, Modernist Maverick: The Architecure of William L. Pereira), made a valiant case for preservation; but his argument devolved to historic/landmark terms: the historic synchrony and east-west symmetry of the Pereira art museum campus at Wilshire and Fairfax and the Welton Beckett-designed campus of the Music Center at First and Grand – both at the fifty-year mark. Miranda and others countered that there were quite a few notable Pereira buildings scattered throughout L.A. (e.g., the LAX Theme Building, CBS Television City) that had a stronger claim for preservation; and still others that would endure regardless of critical repute (e.g., the Variety Building right across the street, which Govan himself praised—not necessarily surprising given that half the LACMA administrative offices are in the building).

Sharon Johnston and Mark Lee, of Johnston-Marklee Architects, who certainly understand transparency, were thoughtful choices to fill the fourth and fifth chairs in the line-up. They’ve only recently designed a museum of their own (the Drawing Institute for the De Menil Collection); their architecture (the little I know of it) puts a kind of California, geometric spin on a post-Corbusier elegance. Both Johnston and Lee were, perhaps not surprisingly, inclined to give Zumthor a pass. (Mark Lee had a funny line about the Pereira LACMA, analogizing the Pereira oeuvre to Bobby Darin’s catalogue of hit pop songs, with the LACMA campus compared to a forgettable ‘B-side’ like “Splish-Splash.”) Johnston had an appreciation for Zumthor’s fluid tentative process and methodology, contrasting it with what she saw as a kind of presumptuous purchase on museum and site in the plan of Zumthor’s predecessor, Rem Koolhaas, who seemed to view the campus as “a totalized object,” as opposed to something that didn’t necessarily need to “reveal itself in an iconic way.” I sort of wondered what Govan might make of that, in that the Zumthor had and has a fairly well-defined, if not iconic, footprint that was probably one of its selling points.

Goldin in turn was eager to pull back the ‘footprint focus’ to the larger context of the place itself; concerned that, in ignoring the “political, cultural, historic process,” Zumthor was making a set of mistakes that paralleled Pereira’s own.

Miranda noted that she had just returned from Chile where she had an opportunity to see LACMA’s collection of Islamic art exhibited in the Santiago Museum’s expansive galleries – and how much better they had looked than in the smaller galleries and “dark halls” of the Ahmanson building. (Although not all the galleries are necessarily small in the Ahmanson, I was struck by her point walking down one such ‘dark hall’ just the other day, and into one of those smaller galleries (to look at the archival “Art and Technology at LACMA, 1967-1971” exhibit.) One thing everyone seemed to agree upon was that we’d all be happy to see the Hardy-Holzmann-Pfeiffer ‘wall’ ripped out as soon as possible.

When Hawthorne brought Govan back on stage for a wrap-up (and I thought – wrongly – audience questions), there was an almost palpable feeling of relief (even among those of us eager to toss him a few questions) – Hawthorne assuming a role that seemed a cross between the chair of a Ph.D. student’s thesis committee and Ryan Seacrest. ‘Well, Mr. Govan, you’ve passed our dissertation review and we’re happy to welcome you into the program.’ ‘So, Mr. Govan, how do you plan to juice up your next performance?’ Given Zumthor’s method, and the issues regarding transparency, gallery perspectives, visibility, Hawthorne gently raised the issue of possible “blind spots,” which Govan deftly turned to his agenda, even venturing (bravely, I thought) into the subject of the access/entrance/exit conundrum – with staircases.

“It’s not a big risk,” Govan confidently glided into seismic zones of controversy; “[Zumthor]’s already built two museums.” Then, hedging again: “It’s a worthy risk.” It might well be. But neither Goldin, nor anyone else had a chance to raise the political/financial/process/context questions Govan’s wager implicitly raised. Hawthorne might be excused for wrapping what was admittedly a long evening; but he clearly recognized the platform and privilege he had given to Govan. There’s also the question of access to this on-going process – a process that takes place largely behind closed doors between Govan and Zumthor exclusively. In Michael Govan’s world, $300 million is a mere bagatelle; even a billion won’t raise too many eyebrows. But a billion dollars is something to a city with a decaying infrastructure and where half the population struggles to pay its bills. For that matter, it was noteworthy that Hawthorne and the Los Angeles Times had been given such exclusive access to this story. Except for a postscript on Hawthorne’s piece that appeared on the Curbed L.A. site, there was no other coverage of the story. Hard to imagine The Wall Street Journal, The New York Times, the Financial Times, and the Guardian blacked out – but there you are. I’m curious about this ‘bromance’ between Govan and Zumthor. Might there be any question of a ‘bromance’ between Govan and Hawthorne?

It may well be time for a new museum building; and allowing for a few qualifications, no one is really clinging to the Pereira campus. (And did we really need that Perenchio PR stunt? Is there anyone in Los Angeles who bought that charade?) The question is whether the Zumthor/Govan museum is that building (and whether we’ll even recognize it if and when it’s completed). In the meantime, we might try to stay focused on the art we plan on putting in it.

-

Officials probe worker’s death at Gagosian’s $70 million NYC mansion

Page Six

An employee of Koenig Iron Works died following a fall at Larry Gagosian’s UES mansion while completing a gut renovation.

-

From Blob to Blot – A Debate Over the New LACMA

And so the Govan/Zumthor/LACMA PR juggernaut thunders on, steamrolling over those skeptical eyes looking over their shoulders from near and far, critics and other local scolds (and possibly its immediate neighbors), to say nothing of its own Board of Trustees, the Board of Supervisors of Los Angeles County and its 10 million citizens or for that matter the Museum’s own membership and core constituencies. Also niftily coopting the hometown press in the process by looping in the Los Angeles Times’ architecture critic, Christopher Hawthorne, a seemingly neutral third party, whose objectivity might be presumed (and trusted) by most of these parties—with the further validating presence of professional/critical colleagues and distinguished (and local) architects.

I’m not faulting Hawthorne either for his opinions or for giving Govan this forum. The forum – which was part of a series of forums, panels and lectures, dubbed (by Hawthorne himself) “Third Los Angeles,” intended to focus attention on the urban evolution of Los Angeles, and in particular what Hawthorne views as the third distinct epoch or stage in this evolution – had apparently been organized and scheduled long before this late March evening. I actually think I’ve learned more about Hawthorne the past couple days than either the LACMA Zumthor project, Michael Govan, or the urban evolution of Los Angeles – about which I have my own theories and opinions. Among other things I learned that in addition to being the Los Angeles Times chief architecture critic, Hawthorne is also a professor in the Urban & Environmental Policy Department of Occidental College (hence Occidental’s sponsorship of the series; KPCC-FM is also a sponsor). Whatever my reservations about his critiques and opinions, I can only applaud what he’s trying to do; I wish I had the time to audit one of his classes.

Whether further spurred on by yesterday’s L.A. Times’ coverage, which was based on reporting that included telephone interviews and extensive conversation with both Govan and Zumthor, or simply his own determination to head off potential scrutiny or hedge new criticism the ‘evolving’ structure might come in for, Govan took the podium like Rahm Emmanuel on the offensive for his municipal fiefdom. It was like an architecture history lecture on steroids – but then that might be a good description of the development of urban (and suburban) Los Angeles. I was grateful to have missed the first 10 minutes or so of this, both because most of this stuff is depressingly familiar to me, and again, I really don’t need to hear another specious gloss on this history.

Govan then pivoted to his personal (after a fashion) architectural history – the projects he has had some role in overseeing or steering through public-private partnership (another buzz-phrase) to completion – e.g., MassMOCA and, that finest of architectural moments, the Guggenheim Bilbao. (Always nice to enjoy a moment in the sun before you jump into the black tar.) From there he moved on to address the original plan of the building and the proposed changes already sketched out in Hawthorne’s L.A. Times coverage in a kind of PowerPoint presentation: the elimination of public entrance through the plinths or support columnar elements that were once envisioned as visually accessible art storage units that the public might move through as they proceeded to the galleries, and consequent shift (and reduction) of the entrances to north, south and/or west sides of the structure; the reining in of the ‘blob’-like curvature into a slightly more trapezoidal massing pivoting westward towards the west side of the LACMA campus, curving in and over Wilshire, before fanning out (again somewhat squared off) eastward. In other words, the Googie shape is now more of a Gumby shape (not necessarily a tragedy, for those of us already inclined to be nostalgic about the original Zumthor blob) – perhaps with a little Richard Serra Tilted Arc thrown in (just so we know that it’s good for us). The interior plan continues to evolve: the interior ‘rat’s nest’ maze broken up and streamlined into six somewhat more coherent trapezoidal sections – alas pushed somewhat away from the circulation – the once mooted ‘verandah’ gallery – around the curvilinear perimeter of the structure; the dozen or so essentially white double-plus height galleries that will penetrate what was once viewed as an unbroken horizontal line; that and other possible variations to what was also originally visioned as a solid black (solar panel) roof and perimeter outline of the curving structure.

Throughout Govan stressed that this was not really a serious break with his original emphasis on the horizontal sprawl of the structure, returning again and again to the point, putatively borrowed from commercial consumer psychology, that visitors are decreasingly inclined to ascend to successive levels in multi-storey cultural (or commercial) facilities – conveniently ignoring the obvious fact that the structure as currently designed demands that visitors ascend to the first gallery level. (Always interesting how much attention is paid to such theoretical points, even as the actual effect is usually some reduction of movement or access – or choice – for the consumer.)

Given some of the remarks he’s made in the past, I have to wonder if Govan’s insistence on the one-floor/one-stop shopping scheme has as much to do with setting things up so he can build yet another ‘satellite’ museum somewhere else. (Last night he mentioned Inglewood – I hope he’s let the Metro transit people know where he wants the next subway line extension.)

He took some pains (or maybe the audience did) to emphasize that these changes reflected, not simply Zumthor’s and the museum’s respect for the La Brea tar pits and the public spaces around the Miracle Mile/Wilshire Boulevard location, but Zumthor’s consistent sensitivity to site. He also took note of Zumthor’s standard modus operandi – moving away from sketches or renderings to actual models and fitting the model with the site. The bottom line is that with Zumthor, you don’t know what you’re getting until you’ve gotten it – not necessarily a bad idea in theory, if you compare it, say, to a fashion designer working directly off the body of a fit model. The only difference is that a standing human body takes up two or three square feet. Here we’re talking about six acres of prime urban turf in the middle of L.A.’s Wilshire Boulevard, including infrastrucure. There can be unintended consequences. (I always wondered what the back story was on the planned museum in Berlin that actually broke ground but was demolished long before completion.)

It was all about the evolution of museums and public spaces. The changes go “on and on” at art museums, he stressed, again completely sidestepping his insistence that the changes stop at his piano nobile mono-level museum; all about – summing up again in bullet points – Transparency, Accessibility, Efficiency, and Sustainability. (In theory, there is a net return of energy to the city’s power grid from the all solar-powered zero-energy structure.)

After Govan had finished powering through this propaganda barrage, Hawthorne got back up on stage to probe tentatively at some of the main points and possibly ‘put a human face’ on them. He had put out the word on the forum to a few architecture/design colleagues some time before the panel/presentation to elicit comments and responses and he read from the commentary he received from design critic Alexandra Lange, which for me was the highlight of the evening, both as a critique of the ‘evolving’ ‘blob-to-blot’ structure, and an eloquent essay on the LACMA/museum experience and cultural experience generally – addressing aspects of the museum experience Govan’s presentation seemed to all but ignore. Lange’s commentary took the point of view of the casual observer, wandering in and out of doors through some of the landmarks of the site, the solitary art encounter framed by the sensual experience of the sights and sounds of the randomly (human) activated architectural space, its materials and atmospherics. Hawthorne then introduced the panel – his Los Angeles Times colleague, the seasoned art and architecture reporter, writer and critic, Carolina Miranda, architectural historian Alan Hess, long-time architecture critic and curator Greg Goldin, and architects Sharon Johnston and Mark Lee (of Johnston-Marklee) – which took the stage without Michael Govan, who then returned to his seat in the front row on the left side of the auditorium.

There was something slightly awkward about this transition – as if an appellant advocate had made his argument, and the case handed over to a panel of judges to arbitrate or come to some definitive decision. It was a difficult case to argue and a difficult decision to make; and if the panel ultimately did come to some consensus, it was not exactly what we would call a clean precedent….

[TO BE CONCLUDED IN THE NEXT POST]

-

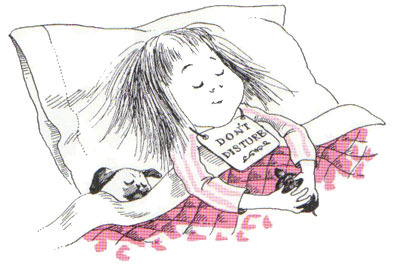

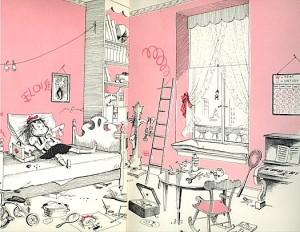

A Class of One: Me and Eloise

By the time I had discovered Eloise (there is only one, you know), I was already well on my way to becoming Eloise – if I wasn’t already. By that time, I had already begun moving away from children’s books and into actual literature. My older brother had already read J. D. Salinger’s The Catcher In the Rye by the age of 7; and I took quite a few of my early reading cues from him – to give you some idea of the track I was on. (I didn’t read Catcher myself until I was about 12, at which point I was already up to my eyeballs in “phonies”; so it wasn’t quite the eye-opener it was for my brother or many of my peers.) I’d already had Madeline, Peter Pan, The Wizard of Oz, et seq.; the E. B. White crew of Charlotte, Wilbur, and Stuart Little; Lewis Carroll’s Alice; Dr. Seuss in every metamorphosis available from The Cat in the Hat to the Grinch; the odd bit of James Thurber and Roald Dahl and a smattering of Grimm and Andersen fairy tales; and about a thousand Little Golden Books that were sometimes consumed before we exited the supermarket where they were purchased.

My parents could not have been more relieved since I developed a mania for almost anything that appeared in a series. (I didn’t discover Carroll’s Through the Looking Glass until I was almost 12, either – which practically induced a delayed spasm of FMO at the time.) My parents never picked up an Eloise book for me (and it would have been only for me, since my brother would have had little interest in playing out what would have clearly been my own fantasy, already veering dangerously close to reality). In retrospect, I think this was wise. Bear in mind that the original subtitle for Eloise (which I don’t think you see on later printings) was “A Book for Precocious Grown-Ups.” Which it sort of was. I was nowhere close to ‘grown-up’ (and sometimes wonder if I ever will be) – but precocious? I wouldn’t have even known what the word meant at five or six; but by that age I already knew who Kay Thompson and D.D. Ryan were, had already been to the Plaza (at least once anyway), had developed a taste for all things French and high-fashion, was passionate about the Metropolitan Opera (and Museum) and the New York Philharmonic, and thought a New York hotel (almost any New York hotel) might be just about the perfect place for a six year-old to live. This was all disturbing enough for my parents. So of course they had to keep Eloise from me.

My parents could not have been more relieved since I developed a mania for almost anything that appeared in a series. (I didn’t discover Carroll’s Through the Looking Glass until I was almost 12, either – which practically induced a delayed spasm of FMO at the time.) My parents never picked up an Eloise book for me (and it would have been only for me, since my brother would have had little interest in playing out what would have clearly been my own fantasy, already veering dangerously close to reality). In retrospect, I think this was wise. Bear in mind that the original subtitle for Eloise (which I don’t think you see on later printings) was “A Book for Precocious Grown-Ups.” Which it sort of was. I was nowhere close to ‘grown-up’ (and sometimes wonder if I ever will be) – but precocious? I wouldn’t have even known what the word meant at five or six; but by that age I already knew who Kay Thompson and D.D. Ryan were, had already been to the Plaza (at least once anyway), had developed a taste for all things French and high-fashion, was passionate about the Metropolitan Opera (and Museum) and the New York Philharmonic, and thought a New York hotel (almost any New York hotel) might be just about the perfect place for a six year-old to live. This was all disturbing enough for my parents. So of course they had to keep Eloise from me.  But unlike the omission of the Alice sequel, I had and have no problem with my delayed introduction to Eloise. You don’t need to be a grown-up to fully apprehend (the apprehension comes before the appreciation) Eloise, but it helps. I was already a noisy brat with an acutely developed aesthetic sense (along with some capacity for make-believe), so I didn’t need any encouragement in that direction. But what Eloise would have drawn out distinctly for me, in a way that I wouldn’t be aware of for at least a few precious years, was a certain class distinction that would have shut down my childhood and a certain part of my imagination a few years too soon. I could already imagine living at the Plaza – that was easily encompassed by my childhood imagination. But my parents weren’t the kind that hopped back and forth across the Atlantic; and as soon as I grasped the implications of “and charge it please,” the details of lawyers, hotel executives and “AT&T stock,” I would have realized that this world was hopelessly closed off to me (to say nothing of many of my suburban New Jersey neighbors and the world at large); and … let’s just say I would have been well on my way to ‘catching up’ with my brother’s ‘Rye-eyed’ jaundice.

But unlike the omission of the Alice sequel, I had and have no problem with my delayed introduction to Eloise. You don’t need to be a grown-up to fully apprehend (the apprehension comes before the appreciation) Eloise, but it helps. I was already a noisy brat with an acutely developed aesthetic sense (along with some capacity for make-believe), so I didn’t need any encouragement in that direction. But what Eloise would have drawn out distinctly for me, in a way that I wouldn’t be aware of for at least a few precious years, was a certain class distinction that would have shut down my childhood and a certain part of my imagination a few years too soon. I could already imagine living at the Plaza – that was easily encompassed by my childhood imagination. But my parents weren’t the kind that hopped back and forth across the Atlantic; and as soon as I grasped the implications of “and charge it please,” the details of lawyers, hotel executives and “AT&T stock,” I would have realized that this world was hopelessly closed off to me (to say nothing of many of my suburban New Jersey neighbors and the world at large); and … let’s just say I would have been well on my way to ‘catching up’ with my brother’s ‘Rye-eyed’ jaundice.  I already had some vague notion of socioeconomic class distinctions; knew that some of our relatives were somewhat ‘richer’ (and that their generosity made some of my early cultural experiences possible). But until I was ten or so, social ‘class’ was something infinitely mutable and flexible; something that was accessed principally by style, or some combination of style and achievement – and sheer imagination. Maria Callas, Leonard Bernstein, Chita Rivera, Jerome Robbins, Richard Burton, Mary Martin, Julie Andrews, Vladimir Horowitz; or the fancy people tripping through the Plaza Hotel, dressed in their Balenciaga and Balmain or Bill Blass and Donald Brooks – it was all the same world to me; and to think so much of it was happening right across the river. It was an enchanting escape for a kid who already knew she was, uh, ‘different.’ The disillusionment of the social/economic realities of credit charge cards, and the securities portfolios behind them, that were the underpinnings of Eloise’s life at the “tippy-top” of the Plaza Hotel could wait. That would have just made me want to “sklonk” someone in the kneecap. In the meantime, our needs could be satisfied by a hotel right around the corner (the St. Moritz) – where the milk shakes and root beer floats at Rumpelmayer’s were unsurpassed.

I already had some vague notion of socioeconomic class distinctions; knew that some of our relatives were somewhat ‘richer’ (and that their generosity made some of my early cultural experiences possible). But until I was ten or so, social ‘class’ was something infinitely mutable and flexible; something that was accessed principally by style, or some combination of style and achievement – and sheer imagination. Maria Callas, Leonard Bernstein, Chita Rivera, Jerome Robbins, Richard Burton, Mary Martin, Julie Andrews, Vladimir Horowitz; or the fancy people tripping through the Plaza Hotel, dressed in their Balenciaga and Balmain or Bill Blass and Donald Brooks – it was all the same world to me; and to think so much of it was happening right across the river. It was an enchanting escape for a kid who already knew she was, uh, ‘different.’ The disillusionment of the social/economic realities of credit charge cards, and the securities portfolios behind them, that were the underpinnings of Eloise’s life at the “tippy-top” of the Plaza Hotel could wait. That would have just made me want to “sklonk” someone in the kneecap. In the meantime, our needs could be satisfied by a hotel right around the corner (the St. Moritz) – where the milk shakes and root beer floats at Rumpelmayer’s were unsurpassed.  The other thing about Eloise – again suggested by the original subtitle – is that this is the expression of an adult giving voice to her inner six year-old. Eloise was actually a voice before she was a book, or even a developed ‘character.’ The story is that Kay Thompson, who wrote the text for the books, was late for a recording session or rehearsal date (in conjunction with her singing/performance career); and upon being scolded by some of the musicians and/or the producer on the date, spontaneously began channelling (in that trademark tiny, scratchy voice) the inner six year-old she called Eloise. “I am Eloise; I am six years old.” The real-life Kay Thompson had (until then) rarely given vent to such impishness. She was a consummate Hollywood professional with a distinguished career both in front of and behind the cameras. As her Hollywood and performance career flagged, though, she was looking for other outlets; and it was that other stylish New Yorker, D.D. Ryan (then an editor at Harper’s Bazaar), who connected her with Hilary Knight. The rest, as they say, is history.

The other thing about Eloise – again suggested by the original subtitle – is that this is the expression of an adult giving voice to her inner six year-old. Eloise was actually a voice before she was a book, or even a developed ‘character.’ The story is that Kay Thompson, who wrote the text for the books, was late for a recording session or rehearsal date (in conjunction with her singing/performance career); and upon being scolded by some of the musicians and/or the producer on the date, spontaneously began channelling (in that trademark tiny, scratchy voice) the inner six year-old she called Eloise. “I am Eloise; I am six years old.” The real-life Kay Thompson had (until then) rarely given vent to such impishness. She was a consummate Hollywood professional with a distinguished career both in front of and behind the cameras. As her Hollywood and performance career flagged, though, she was looking for other outlets; and it was that other stylish New Yorker, D.D. Ryan (then an editor at Harper’s Bazaar), who connected her with Hilary Knight. The rest, as they say, is history.  The flip side of that ‘inner six year-old’ is that it’s also not infrequently the voice of a willful, neurotic, selfish, co-dependent, substance-abusing/intolerant, and imbalanced (and/or undisciplined) adult. Speaking as one of those permanent six year-olds, this does not always make for merriment.

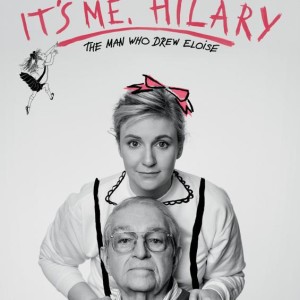

The flip side of that ‘inner six year-old’ is that it’s also not infrequently the voice of a willful, neurotic, selfish, co-dependent, substance-abusing/intolerant, and imbalanced (and/or undisciplined) adult. Speaking as one of those permanent six year-olds, this does not always make for merriment.  Which brings us to this evening’s HBO documentary, It’s Me, Hilary: The Man Who Drew Eloise, produced by Lena Dunham and Girls’ producer Jenni Konner and directed by Matt Wolf. I’m sure it will be reasonably entertaining; and I’m planning on watching it with my sister (who puts up with a good deal of my adult Eloise-hood, while having been fortunate enough to have missed the actual Eloise years of my life). But part of me chafes at Dunham’s seeming appropriation of the character (and I confess to some jealousy of her adoption of Hilary Knight, whose work I’ve long admired, not just as the creator of Eloise, but as a great illustrator). Here’s the thing: I don’t think Lena Dunham is old enough to appreciate that inner voice of Eloise. I don’t mean that generationally. I mean that I’m not sure I find it credible that Dunham had access to that particular Skipperdee-Weenie-doll-bleeding-knee-sklonking-ballroom-haunting-closet-sklanking sensibility at age 6, or the abject-arrogant-stage-fright-flight-aggressive-regressive-yes-I-drank-too-much loneliness of 6×5(x2) that gives voice (and bite) to it. I haven’t seen any reviews yet (though I see that The New York Times put one up sometime this morning), so I’ll withhold judgment. But oh my lord I don’t know how they’re going to bring back that voice and viewpoint. I’ll settle for Hilary Knight’s.

Which brings us to this evening’s HBO documentary, It’s Me, Hilary: The Man Who Drew Eloise, produced by Lena Dunham and Girls’ producer Jenni Konner and directed by Matt Wolf. I’m sure it will be reasonably entertaining; and I’m planning on watching it with my sister (who puts up with a good deal of my adult Eloise-hood, while having been fortunate enough to have missed the actual Eloise years of my life). But part of me chafes at Dunham’s seeming appropriation of the character (and I confess to some jealousy of her adoption of Hilary Knight, whose work I’ve long admired, not just as the creator of Eloise, but as a great illustrator). Here’s the thing: I don’t think Lena Dunham is old enough to appreciate that inner voice of Eloise. I don’t mean that generationally. I mean that I’m not sure I find it credible that Dunham had access to that particular Skipperdee-Weenie-doll-bleeding-knee-sklonking-ballroom-haunting-closet-sklanking sensibility at age 6, or the abject-arrogant-stage-fright-flight-aggressive-regressive-yes-I-drank-too-much loneliness of 6×5(x2) that gives voice (and bite) to it. I haven’t seen any reviews yet (though I see that The New York Times put one up sometime this morning), so I’ll withhold judgment. But oh my lord I don’t know how they’re going to bring back that voice and viewpoint. I’ll settle for Hilary Knight’s. In the meantime, I know where Skiperdee is living. (He lives in and around a fountain at my former psychologist’s house/office.) I’m still looking for a proper Nanny. (It’s okay if you still smoke.) I am a city child and I miss New York. I am Ezrha Jean; I am six years old.

-

Cry the Occupied Country – Figaro’s Dance and A Countess’s Lament

Do you ever wonder what happened to the Occupy moment? We can’t really call it a movement because it had no coherent program, plan or organization, no well defined or articulated policy (or revolutionary) objectives; and its only concrete target was a somewhat vaguely defined index of commercial and investment banks, securities brokerages, insurance exchanges, private equity and hedge funds. I’m not even sure if any of the principal instigators knew what they really wanted. Break-up of the ‘too-big-to-fail’ financial entities seemed to be pretty high on the agenda. But did anyone really have any clue how this might be accomplished in a political environment that had shifted from steady rightward drift into wholesale paralysis? (It’s as if our national governmental organizations have gone into deep freeze over the last several years or so in direct proportion to the planet’s climate warming – with similarly disastrous results.)

The vagueness of Occupy’s objectives, along with the complete absence of a rigorously programmatic, practical and truly radical agenda and strategy doomed the movement almost before the tents were cleared from Zucotti Park and (here in L.A.) the City Hall lawn. But the political psychology is pretty clear. We’re an occupied country here; and the essential changes that will be required are mostly not going to come from the existing political structures – nor from the private and corporate interests that are doing most of the occupying. The changes come from a community’s cultural life, which may reflect both Establishment and Dis-Establishment interests. The Los Angeles Opera has joined this ‘battle royal’ over the last couple of months with one lavish original production and two older productions spruced up and recharged by electric performances.

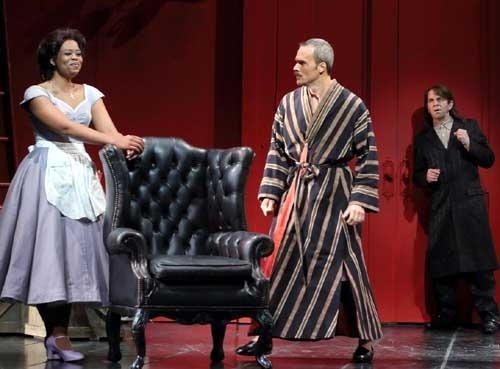

I don’t think L.A. audiences really needed much of an argument to interpose John Corigliano’s The Ghosts of Versailles in place of the actual third play in the Beaumarchais Figaro trilogy, La mère coupable (The Guilty Mother). Ghosts presents us with a visceral connection with the living tissues of history and inexorable ravages of time and physical forces beyond our control – and their resonance with the crises of the current historical moment. (There is in fact an opera based directly on La mère coupable by Darius Milhaud, with the libretto by his wife, Madeleine.) What I loved about the current production of Mozart’s Le Nozze di Figaro, which just opened this past Saturday evening, was an uncanny capacity, not merely to suggest the possibilities that unfold in La mère coupable, but to subtly articulate and underscore some of the unresolved conflicts both in the original Beaumarchais dramatic foundations and in the entire thematic notion of ‘Figaro Unbound.’

If there was ever a figure that defied the social and political boundaries of his time, it was the original Figaro himself, Beaumarchais. But, as Susanna and the Countess remind us in different ways through Mozart’s opera, such legerdemain is not so easily procured by the 99 percent (and still more emphatically, its feminine half). The current production is essentially the same production I saw in 2006 – with the same deliberately anachronistic set decoration and costuming. Whether or not (given the opera’s farcical parade of characters) an argument could be made for it, I found it creakily annoying the first time around. This time, I was happy to completely forget about it and could almost be amused by the Countess’s first appearance in her 1930s-ish bedroom with its 1950s-ish telephone. I’m as easily annoyed as ever (as readers of this blog are only too aware). The difference – for the entire production – can be summed up in three words: casting, choreography, and chemistry. The program credits the original director Ian Judge and choreographer, Sergio Trujillo, with additional credit given to choreographer Chad Everett Allen. I can’t pinpoint exactly where Allen has interposed changes to the characters’ movements and interactions; and there are a few moments where the stage blocking or character line-ups still seem a bit stiff – but whatever he changed or added and wherever he did it brought a fluidity and grace notably absent from the 2006 production.

Did I mention the casting? It’s the old cliché of film and theatre direction and it applies no less here: the secret of good direction is great casting. The spotlight in recent weeks has been on the return of Pretty Yende to the L.A. Opera stage in the role of Susanna after her triumphs at the Met and Carnegie Hall – and she was great, though the role doesn’t really offer a scope in full measure with her vocal power. The surprise was that pretty much everyone in the cast rose to the same level. It was as if we were constantly echoing the Countess’s second act compliment to Cherubino, “Che bella voce.” Certainly that included the Countess herself, Guanqun Yu, whose exquisite voice shone through some difficult bedroom maneuvers (suggesting an aristo Maggie the Cat) in the same act and throughout the opera in what may be its most challenging role. Roberto Tagliavini (Figaro) and Ryan McKinney (the Count) were both commanding in their respective roles, a constant reminder of the power of great musicianship wedded to stage charisma.

The stage chemistry was particularly strong in scenes featuring Yende, Tagliavini, McKinney, and Yu; and the subtle emotional articulation was evident in their most brisk recitatives; the political implications of their dark double entendres foregrounded as much as the sexual. In various scenes throughout the opera, you felt a foreshadowing not only of Beaumarchais’ Guilty Mother, but so many other treatments of these themes and motives, from Strauss (e.g., Der Rosenkavalier) to Sondheim (A Little Night Music).

The Countess’s gracious magnanimity lights up the darker recesses (key to any staging of this opera) of Beaumarchais’ original farce. But even as the fireworks (live pyrotechnics in this staging) lit the characters’ way to the nuptial revelries, even as Figaro leaps away ‘unbound,’ we’re acutely aware of the chains (not just jewels) that keep these strong women tethered to their places. It’s far more explicitly underscored in the play in Susanna’s (or Suzanne’s) final speech:

Qu’un mari sa foi trahisse,Il s’en vante, et chacun rit:Que sa femme ait un caprice,S’il l’accuse, on la punit.De cette absurde injusticeFaut-il dire le pourquoi?Les plus forts ont fait la loi.Let a husband break his vows,

It’s just a joke the world allows –But should a wife like freedom take,The world will punish her mistake.The strong it is for all they sayWho in the end will have their way.That’s from the John Wood (Penguin edition) translation, by the way. The original French is actually a bit more harsh. ‘Is it really necessary to question this absurd injustice? The stronger make their own law.’ They’re still making it. (It’s as if the entire point of their Congress is to not make any laws that complicate the economic ‘laws’ their financial maneuvers and machinations dictate.) “Se mi salvo da questa tempesta, / Piu non avvi naufragio per me,” Susanna and the Countess sing as they watch Figaro try to dodge the Count’s wrath in his mad third act jig on Cherubino’s behalf. “If I survive this storm / I’ll fear no further shipwreck.” Two hundred thirty years later, that sounds awfully familiar.

-

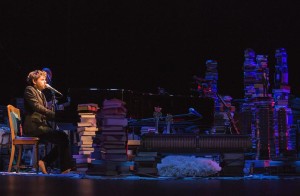

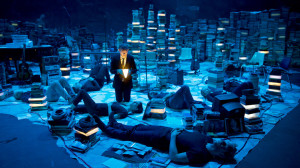

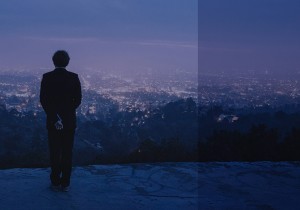

Manifest Destination: Gabriel Kahane’s The Ambassador

Having followed Gabriel Kahane’s songwriting career for some time, I was primed for a terrific show this past Saturday evening at UCLA’s Freud Playhouse. Kahane has the dual gift of an innate musical talent and extraordinary musicianship wedded to a peerless gift for story and narrative. He’s the kind of songwriter completely unabashed about showing his influences, both songwriting or purely musical and literary, because his own voice is so strikingly original and effortlessly dominant. Just in case I might have forgotten, Bill Raden’s L.A. Weekly piece reminded me that Kahane’s staged presentation of The Ambassador, his album of L.A.-inspired songs released last summer, might be a must. (The Los Angeles Times followed with a feature of its own the following day.

Hollywood looms large over Kahane’s vision—from film noir to disaster movies to sci-fi, to, still more specifically (directly quoting here), “action movies of the 1980s.” Even literary (e.g., Chandler) and architectural references (iconic monuments of mid-century domestic architecture doubling as film locations) are filtered through a motion picture lens. But there was a performative quality to this song cycle long before Kahane ever actually performed (as far as I’m aware) any of them publicly—something of the troubadour’s loosely connected narrative-in-song of a pilgrimage; or a passion play strung between eccentrically placed stations. The Ambassador is something of a throwback to a time when songwriters and musicians consciously shaped collections of songs into albums that, even without a strict conceptual frame, cohered into a unified vision. (Unsurprisingly, these include some of the songwriters whose influence is most apparent.)

Hollywood looms large over Kahane’s vision—from film noir to disaster movies to sci-fi, to, still more specifically (directly quoting here), “action movies of the 1980s.” Even literary (e.g., Chandler) and architectural references (iconic monuments of mid-century domestic architecture doubling as film locations) are filtered through a motion picture lens. But there was a performative quality to this song cycle long before Kahane ever actually performed (as far as I’m aware) any of them publicly—something of the troubadour’s loosely connected narrative-in-song of a pilgrimage; or a passion play strung between eccentrically placed stations. The Ambassador is something of a throwback to a time when songwriters and musicians consciously shaped collections of songs into albums that, even without a strict conceptual frame, cohered into a unified vision. (Unsurprisingly, these include some of the songwriters whose influence is most apparent.) What this brilliantly conceived and executed staging by John Tiffany and his fabulous production team captured was the magic lantern quality of film images and the movies themselves (as originally produced for the darkened ‘magic box’ of the movie house) in their analogue relation to the space of personal memory, dreams and the intersections of both in the real world of events played out in public and private spaces. But this is above all a personal journey—a mapping of that interior space onto physical and historical space. It begins in the smallest space—for all Kahane knows, it could be the womb—the backseat of an automobile, an elevator car. Behind all the dread and foreboding is a vague suspicion that it’s all foreordained—bred in the bone—as narrated in one song (“Empire Liquor Mart”) by the lovely bones of one of the youngest victims of the 1992 post-Rodney King riots. It’s a vision that’s both anarchic and almost claustrophobic. You don’t necessarily need a native voice to articulate this dread (e.g., Joan Didion). We brought it with us—whether we were traveling by prairie schooner or jet plane, Santa Fe Railway or Route 66.

The challenge for the stage production is in connecting those finely observed fragments of micro-memory (e.g., a mother’s “earrings” and father’s “sunburn,” the “old man” in a “Westin Bonaventure Hotel” elevator) into the larger journey limned by the song cycle—to the places where memory goes from ‘faded to forgotten.’ (I thought it just slightly ironic that Kahane should see the end here, under a ‘sea splitting the pilasters,’ when New York’s Grand Central is no less likely to find itself submerged; a no less ironic but fitting coincidence that Kahane should set this envoi in “Union Station,” where scarcely more than a year ago, The Industry staged the Christopher Cerrone opera, Invisible Cities.) But I also heard the song cycle as a mission of rescue and retrieval—“The Ambassador” referring not only to the late Ambassador Hotel, but a sort of Jamesian anti-hero, desperate to retrieve not necessarily a lost ‘self,’ but an idealized vision of life’s possibilities.

With a view toward keeping those small moments alive, while surveying the broad desert-to-sea basin floor range of the journey, Kahane and Tiffany trace the elusive connections with a spare but richly atmospheric setting, both in terms of the staging (props, placement, lighting) and the musical ensemble (eight musicians, including Kahane, beautifully deployed). At one point, the strings (violin, viola and cello) continued bowing while rolling on their backs in a slightly fetal curl. Alex Sopp did triple (or quadruple?) duty in a long, very geometrically cut skirt and cropped top, providing sustained back-up on keyboards, interrupted only by her own vocalizing, flute solos, and choreographed movement amongst props and fellow players. Stacks of books, CDs, old VHS cassette tapes, and the odd lightbox made a city of high-rise detritus, alternately flickering in the shadows and set aflame on cue by Christine Jones’ excellent lighting, and further enhanced and enriched by audio and visuals from obsolete technology: reel-to-reel tape deck, photo slide transparency carousel, etc. These provided a kind of connective tissue to the production (though the architectural model—of the (I think) Neutra Lovell “Health” House—was a bit of a stretch). It was wonderful to hear Bogart in a bit from The Big Sleep; a voice I think was James Ellroy’s reading from either one of his own novels (Perfidia?) or Mike Davis’s City of Quartz, I can’t be sure—which may be one more proof of Kahane’s larger point.

I thought the ending was magical, with its serene recessional of the musicians (a kind of ‘farewell’ elegy) punctuated by Kahane’s epiphanal opening of a light ‘book.’ It takes a certain willfulness to ‘drown history,’ suspend motion, confront the “anguish, anger and aspirations,” and take the long view through the sunlit haze bathing L.A.’s bleak basin—and perhaps a certain faith to, as Didion’s Maria Wyeth put it, “go on playing.” Our ‘Manifest Destiny’ is fueled by our manifest desperation. But the song, the story, the journey create their own reward. What isn’t lost ‘like tears in rain’ (Kahane nods to the power of that transfigured cinematic moment) is the power of Kahane’s musical voice—richly textured, rhythmically and harmonically inventive—and lyrical gift—both impossible to categorize; and a vision to equal that scope.

I thought the ending was magical, with its serene recessional of the musicians (a kind of ‘farewell’ elegy) punctuated by Kahane’s epiphanal opening of a light ‘book.’ It takes a certain willfulness to ‘drown history,’ suspend motion, confront the “anguish, anger and aspirations,” and take the long view through the sunlit haze bathing L.A.’s bleak basin—and perhaps a certain faith to, as Didion’s Maria Wyeth put it, “go on playing.” Our ‘Manifest Destiny’ is fueled by our manifest desperation. But the song, the story, the journey create their own reward. What isn’t lost ‘like tears in rain’ (Kahane nods to the power of that transfigured cinematic moment) is the power of Kahane’s musical voice—richly textured, rhythmically and harmonically inventive—and lyrical gift—both impossible to categorize; and a vision to equal that scope.