RICHARD ARTSCHWAGER WAS AHEAD of his time. In 1964 he painted the Whitney Museumon Madison Avenue with the documentary precision of black and white. It was, for the record, a cloudy day. <!–more–>

Only one thing: the building dates from 1966. Artschwager painted the planners’ vision with his characteristic detachment, on Celotex, the fiberboard then being used as ceiling tile. It functions as a kind of signature for an artist who does everything he can to reject expression or a signature style. With his icy mix of photorealism, pop art, conceptual art and industrial materials, Artschwager was making post-minimalism from the very dawn of Minimalism.

His exhibition runs at the Whitney, a floor above Wade Guyton, a much younger artist who has earned a similar label, which makes Artschwager at age 88 seem even more forward-looking. Yet in the space of six years, starting in 1962, he produced a full body of work. It includes his lozenge-shaped “blps” and exclamation points, both with their 3D counterparts in formica or rubberized horsehair. Not many artists seem less likely to raise their voice, but an exclamation point also enters the retrospective’s title, “Artschwager!”

The years covered by the exhibition include Artschwager’s period of thoroughly nonfunctional geometry made with lamination on wood. No one will ever touch the stops of his organ, set their feet under his table, or turn the pages of his imposing book. No one can, for they are solid blocks. Moreover, rubber bristles line the few objects that have recesses, like an otherwise empty drawer.

Artschwager’s is a world claiming absolute authority, like the open book, seemingly a huge Bible or Koran, merged with its pedestal. It is also a world in the process of self-destruction, as with Train Wreck from 1968 or a whole series on high-rise demolition from the early 1970s. A self-portrait hangs alongside portraits of George W. Bush and Osama bin Laden, with the latter looking benevolent by comparison. There’s a natural segue here from political self-destruction to environmental catastrophe. It seems only right that Artschwager lost Celotex as a material because lawsuits over asbestos helped drive it to bankruptcy.

Artschwager had his first solo show at Leo Castelli in 1965 when he was 42. He took up art after studying science, a background that may reflect his near-clinical detachment. He made furniture for money, presumably functional furniture, and photographed babies. Another early Celotex shows a baby smiling, and it is not heartwarming. One can look for parallels in Andy Warhol, another artist with a commercial background and a decidedly morbid side.

Guyton may not seem like an heir to Minimalism. During his childhood in small-town Tennessee he did not enjoy art classes but preferred video games and TV. This surely establishes his credentials for contemporary New York. The Whitney calls its mid-career survey”Wade Guyton OS,” as if he were competing with OS X Snow Leopard or Mountain Lion. The dominant motif is an X. Guyton sets it there with an ordinary inkjet printer.

Much of Guyton’s early output amounts to book pages fed through such a device, cataloging such influences as Joseph Beuys, Martin Kippenberger, and Mies van der Rohe. Together, they operate between painting, conceptual art and design—and so does he. The show’s largest works consist of red and green stripes, akin at once to Kenneth Noland and Christmas wrapping paper. They are also site-specific, framing the trapezoidal depth of a Marcel Breuer window.

Already the simple design elements suggest Richard Tuttle, but now Guyton nurses them as painting. He folds the linen in half before feeding it through twice, allowing for misalignments. He accepts the printer’s traces as smears, but they feel like an artist’s pride in gesture. Like Artschwager, Guyton puts the Post in Post-Minimalism.

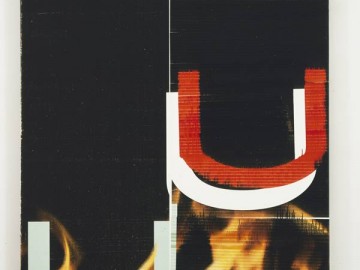

The Whitney sticks to Guyton’s solo act rather than also showing his collaborations with Kelley Walker. A Gen-Xer born in 1972, Guyton appeared among emerging artists at PS1 in 2005, smashing a found Mies tube chair into elegant twists. A work from 2007 could pass for industrial chairs, too, in a long row of shining metal that could pass for a single sculpture. It also brings in a second letter, “U,” the same letter that stands against images of fire from Guyton’s oeuvre the year before.

The “U” could refer to YOU and to US, but Guyton’s strength is not depth allusion. For now, it is his operating system, and that may well be enough.

“Richard Artschwager!” runs thru Feb. 3 and “Wayne Guyton OS” thru Jan. 13; whitney.org