For more than 10 years, starting in 1998, Zoe Leonard photographed the ravages of urban life. From New York to Eastern Europe, Africa, Cuba and Mexico, she found shuttered storefronts and fallen marquees, makeshift signs and dated logos, obsolete computers and manual typewriters, and everything and anything left out for trash or for sale.

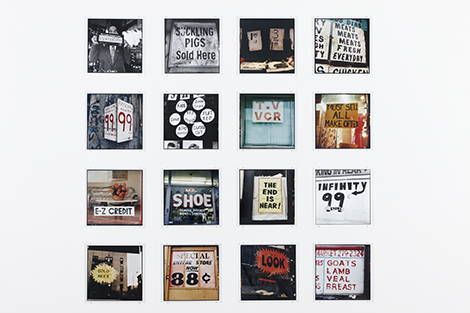

Leonard has every right to judge wasted space, for through August 30 the results occupy MoMA’s atrium, where Martha Rosler, Marina Abramovic and more have come to grief before her. It resembles less a museum display space than the perpetual shopping mall of a global city. Leonard, though, can claim a closer fit. Her Analogue, now in the museum’s collection, can even claim the trappings of urban efficiency—the work’s more than four hundred photos arranged in tight grids of 25 “chapters.”

The series is both a tribute and a warning. It begins on the Lower East Side, where she lived, and it has the pulse and variety of a city walk. Bundles of materials present tapestries of color. Bags of grain attest to the planet’s diversity. Still, Leonard means to document displacement and loss in an age of globalization. One can never know from the images just what is where.

Analogue also helps make sense of her work as a whole. Like many today, Leonard moves easily, maybe even too easily, between subjects and media. She has left out blue suitcases, mounted a tree on scaffolding, and photographed a model of New York as if flying above it. For the 2014 Whitney Biennial, the museum’s last on Madison Avenue, she captured its surroundings with a camera obscura. One can see her as always on the move, while calling attention to the fragile and fleeting context that she leaves behind. For Analogue she adopts means that others have left behind as well, with a 1940s Rolleiflex camera.

Zoe Leonard, Analogue detail. 1998-2007, Analogue was made possible through the Artist’s Residency program at the Wexner Center for the Arts at The Ohio State University. Acquired through the generosity of the Contemporary Arts Council of The Museum of Modern Art, the Fund for the Twenty-First Century, The Modern Women’s Fund, and Carol Appel

MoMA compares the results to Rosler’s documentation of real estate on the Bowery, Los Angeles for Ed Ruscha, Paris for Eugene Atget, or America for Walker Evans. Yet Leonard has little interest in particulars or preservation. She does not have Rosler’s outrage, Ruscha’s dispassion, or Atget’s cultivated beauty. She has no individuals in view at all. She comes closest to Evans when he collects penny pictures and postcards. Consider, though, another model entirely, in Charles Baudelaire.

In “The Painter of Modern Life,” the French poet saw the key to the present in cities—and in the flâneur, or idler, exploring them. “For the perfect flâneur,” he wrote, “for the passionate spectator, it is an immense joy to set up house in the heart of the multitude, amid the ebb and flow of movement, in the midst of the fugitive and the infinite.” Leonard is looking for analogs, in analog media, like Baudelaire with the entire world at his feet.

Like globalization, Analogue can be drab and leveling. Yet it has the charm of the familiar in its planet-wide space of waste.