You find out about Cosey Fanni Tutti’s various bodies of work by rumor or implication—did you know that someone once did this? Did you know it was the same woman who did that?

Cosey started out as a little girl named Christine Newby, in Hull, in the U.K., in 1951. She became a major force in COUM Transmissions, an experimental performance collective that moved in the same circles as Anish Kapoor, Carolee Schneemann and Fluxus—then she moved on. She helped invent industrial music via a strict regime of guitar abuse as one quarter of the punk-era experimental combo Throbbing Gristle—then she moved on. She made sexually charged performances and installations risky enough to enrage Tory MPs and disturbing enough to turn the stomachs of artists who are still celebrated today as transgressive pioneers—then she moved on.

Sentences that usually sound like art-school posturing are, here, coldly accurate: Cosey isn’t in it for the fame. Cosey doesn’t care about money. Cosey breaks the rules. Cosey’s ex threw a shoe at her head and she politely asked for the other one to keep the pair together. Cosey was in an illegal porn orgy that got raided by the police and everyone panicked until they realized the cops were part of the movie. Cosey’s art is her life. Cosey was ahead of her time. Cosey was a true original. Cosey is forever experimenting. Cosey DGAF. Cosey incarnates total risk, freedom, discipline.

These days she makes music with her longtime partner and Throbbing Gristle veteran Chris Carter as half of “Chris and Cosey” and with Nik Void as one-third of “Carter Tutti Void.”

In Art Sex Music, the mother of all musician-artist-pornstars unpretentiously records how that happened.

Bookcover

Zak Smith: You describe your motivation for a lot of the early projects by saying you were trying to transcend your personal boundaries—but you don’t actually talk a lot about what those boundaries are. What was holding you back?

Cosey Fanni Tutti: I think the impulse came from—it was quite a subliminal thing really—came from the fact of being born in the era where women were subservient to men. We had our lives planned out for us really with sort of limited choices—but I was also lucky that I was born into the ’60s when people started challenging that and looking for an alternative way of life.

So, as a very small child I was pretty rebellious anyway and I don’t know where that came from. I have no idea, my mum always used to say I was like my father, he must’ve been a bit of a …troublesome child because he was put out to another family at quite a young age.

Well there was that great story where he tells you to go over to another girls’ house with a pair of scissors and go “If you mess with me again I’m coming back with these scissors.”

They were garden shears for trimming the hedge, they weren’t even hand scissors. So, it’s like—yeah they’re like scissors but pretty big, so—yeah—it was a weapon.

My father, y’know, had wanted a boy so he kind’ve tried to make me like a boy in a way—which I’m pretty pleased about because it made me straddle the male-female gender issues and I think possibly that’s why things turned out the way they did for me. Because I grew up feeling that I had the right to do what both sexes did at the time.

It often seems like—especially in the early days, with everyone living and working in close quarters, until Chris shows up—you had to take care of everyone and make sure they were accommodated on top of your own experiments.

Yeah, but in a way it was also a way of me controlling my own situation, because whatever they were doing impacted on me. If the house wasn’t clean it impacted on me, if there wasn’t food on the table that was something I had to deal with. So in some ways you have to turn it around a little bit and think of me trying to keep control of my own world and myself in relation to other people trying to control me.

I definitely know that dynamic where you have several creative people working together and the person who does the responsible stuff—everyone will turn around and go “You’re trying to control everything!” and you go “I just wanted to have lunch?”

(Laughs) Yeah—“How do you think we’re gonna get from A to B to even do the action?” We need petrol in the van, we need the van to begin with, we need a roof over our heads.

Yeah—“I was the only one who wasn’t hung over so I ordered food.”

Exactly, and then people just accept that role in the end and then they end up relying on you—and then you get a bit pissed off that you’re doing everything. And when you do leave people are lost, I suppose.

I feel like making music is about everyone falling into a role and then getting angry at the role they’ve chosen.

(Laughs) In some ways—I was never angry, I don’t think I was angry …

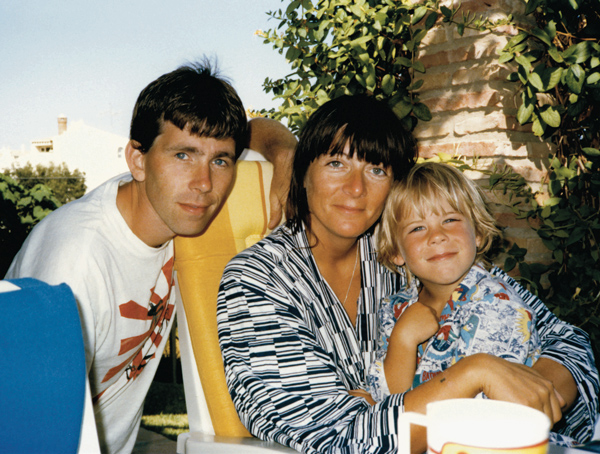

Chris, Cosey and Nick in Spain

In the book, Chris comes across as being a sort of technical genius, constantly making new gadgets and fixing things—I think a lot of people who know industrial music now from things they do on a Mac may not get that in order to make those sounds he had to literally make those sounds—out of, like, bubblegum and springs …

COUM up to that point was really ad hoc and if something broke it never got fixed, whereas with Chris he would like—Well, a really simple example is this and it’s really mundane but it sorts it out:

When I was doing my solos and everything, if ever anything went wrong I would just abandon it. I remember doing that one day and Chris coming in saying “Why have you done that?” and I said “Well, it’s because it’s gone wrong,” so he said “Well, why don’t you put it right? Why are you just going to abandon all that hard work and never go back and put it right? Because then, you know, you’ll never repeat the mistake again” and I looked at him and thought “Yeah he’s right isn’t he?” (laughs) and he brought that to me.

He brought discipline to me in that respect—that you don’t abandon something just because it doesn’t go the way you wanted it to go. He was needed at that point in time for Throbbing Gristle to—and for industrial music to—happen. If he hadn’t been there it wouldn’t have done.

It seems like a kind of anti-showmanship is at the center of your personality as an artist—like you’re going to show up and sit down and play your guitar or take off your clothes and if the audience gets it, good—I just have to do this. In the ’70s there were a lot of artists who focused on showmanship and almost nothing else—and you kind of go in the opposite direction.

I think so, yeah, but also there’s like with Throbbing Gristle we have the TG “flash” and graphics on the stage. And as Chris and Cosey we had our videos—but then again they were our videos that we created. We had images that we put together that could fall nicely into place with sounds that we were making—or not—and quite often they did but that was the whole point of it—was that the visuals were open to interpretation depending on what we played at that time. So that some people might say that that’s showmanship but for me that’s just presentation. And another reason is to have something for people to focus on so they didn’t look at us—it’s not about us; it’s about the work.

In the art sphere—so many of your actions are hard to find or aren’t well recorded. Like “Towards the Crystal Bowl”—where you’re in a Plexiglas cube full of silver polystyrene granules and you’re doing a dance and people can see you coming in and out of the silver and it sounds amazing but I can’t find a picture of it. On the one hand I get that it’s not about the record for you, it’s about doing it, but on the other hand—there’s no record.

Yeah, but it’s about that moment, isn’t it? And I think a lot of people forget that—it doesn’t have to be recorded or put up on Instagram or YouTube or anything. The important thing is that you’re doing something, it’s not that you have to show it to everybody… And it’s the cost of it as well—there were times even in COUM that we couldn’t even afford the film for the camera.

It’s impressive the degree to which there wasn’t much attempt to record COUM or brand it or package it into an art career so that you could prove that you did it or get more arts funding or whatever. You were okay with having a day job, you weren’t trying to pay the bills. It was unusual even at that time.

I suppose it is because we knew artists who were doing that—they had a career path if you like. But part of the whole COUM thing for me is that freedom starts with—the concept of what you’re going to do is—it’s completely free of anything like that.

You just open up the channels—you don’t have to think “I can’t do that because the funding might be affected.” You don’t think “I can’t do that because I can’t get a photograph printed and then give it to anyone.” It’s a case of just freeing yourself up completely, and if you’re independent you don’t have to think of things like that.

It seems like you do draw a distinction between things that you all did that were art and things that you all just do because people were hippies and they were high and doing weird things. Where’s the distinction between doing something extremely eccentric because you’re doing it and “Okay this is an art project”? There’s a blurry line there I think.

Oh there is. I mean I would call some eccentrics artists, sure.It’s just that they’ve not been given the label or the certificate.

Right, but I mean you decided to apply it to yourself at some point—you weren’t just sending people weird postcards, you were “making mail art.” You weren’t just stripping; you were doing your “Prostitution Project.”

Because I viewed my life—like I’ve always said—as my art. So whatever I did—to me—was my art, and I think that’s very true for a lot of people.

In one of your performances you did manage to gross out Chris Burden.

(Laughs) Yes. I don’t know—I think once you get into doing that you do wonder “What’s wrong with what I’m doing?” I have no idea.

On the one hand you do just seem to be casually transgressing lines that make other people uncomfortable—but on the other hand you definitely made a point of doing it. Are you doing it partially just to show people that they don’t need to be afraid?

I think the main drive behind things like that is that I’m doing something that is new to me. Therefore it has a discomfort element to it because I don’t know where it’s going to go. So I’m aware that I’m doing it in that respect, and I’m also aware that people are wondering why the hell I’m doing it only because it’s something that they wouldn’t do themselves. But that’s not to say that you can’t open it up for discussion—and why is it, you know, transgressive? I don’t know because I’m just doing it.

You know Sasha [Grey, porn actress and musician who worked with Cosey in 2012]—porn people get a lot of the same resistance, still. It seems like every generation has to keep planting the same flag in the same place and say it’s okay and we’re allowed to do these things and fight the same people over the same space.

Well they want to pull you back and then kind of reform everything and put boundaries in again and it’s usually because of—I don’t know—fear of people’s freedom to be who they are and not be afraid of sex.

Because I think the point of it is that sex is a really powerful thing. It does drive all of us and without it we wouldn’t even exist, obviously. But also if you think of all the scandals there’ve been in governments, in the church and everything else, it’s an issue that has to be addressed and it has to be worked out so that people feel comfortable with themselves—so they don’t have to do horrendous things to other people to, you know, to satisfy themselves. That’s where society has gone wrong—they’ve ignored that impulse and that impulse has been put to really bad use because of that.