Full disclosure up-front: I am well-acquainted with Zak Smith as an artist. Before we met (in 2010), I was aware of his work only because of his inclusion in the 2004 Whitney Biennial, and not incidentally because his work for that show had (what was for me) an irresistible hook: Pictures of What Happens on Each Page of Thomas Pynchon’s Novel Gravity’s Rainbow.

The Torrance Art Museum will be opening an exhibition of Zak’s recent work—An Unburnt Witch: Zak Smith Drawings—on March 25th, to run through May 6, 2023.

Before I get into that, I have an embarrassing confession: I’ve never finished Thomas Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow. This is much more embarrassing than the reader might presume (although I’m guessing some percentage of Artillery’s readers have already turned away from their phones or laptop screens in disgust). I haven’t finished Middlemarch or The Brothers Karamazov or Moby Dick, either. Or, uh … Proust.

Before I get into that, I have an embarrassing confession: I’ve never finished Thomas Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow. This is much more embarrassing than the reader might presume (although I’m guessing some percentage of Artillery’s readers have already turned away from their phones or laptop screens in disgust). I haven’t finished Middlemarch or The Brothers Karamazov or Moby Dick, either. Or, uh … Proust.

Okay, so now that I’ve surrendered all pretension to cultural credibility, maybe even literacy, allow me to explain how this should stand out as particularly egregious amid a sea (or at least a great lake) of such epic fails. Between my freshman and sophomore college years at U.C., Santa Cruz, Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow was the book of the moment. It seemed as if almost everyone in my class had read it and had something to say about it. I think there was a period of several months where if you hadn’t read or weren’t reading the book, you might just as well take your meals in your room alone. And physics exams were so not an excuse.

About two years later, I was working at The Rand Corporation (long story)—not exactly known for its literary scenesters or alt-cultural types—and it was exactly the same: everyone appeared to have read it. That said, this was a pretty literate group of professionals; also pretty obsessed with rocketry.

Flash forward … a lifetime—past the century mark to 2004, and another Whitney Biennial—one that drew attention from across the country, and not just because of its scope (104 artists)—but one that I missed. It seems even more ironic given how many of the Los Angeles-based artists I knew in it, and that only two years later the Biennial among so many other shows would be part of my routine. Zak Smith (then based in New York) was one of those artists. Pictures of What Happens on Each Page of Thomas Pynchon’s Novel Gravity’s Rainbow was the work exhibited in the Biennial—consuming an entire wall of the exhibition.

The very notion of such a project was inherently fascinating to me, but until 2009 or 2010, I had only seen a handful of the frames (or pages) that constituted this enormous installation (now at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis). I thought of them as frames at the time, though it was clear exactly how Zak had gone about making them. The novel (or what I remembered of it) registered as almost composited images or vignettes in my memory more than story threads or plot points; and it was interesting how some of these images picked up that quality. I wondered if the complete grid of the drawings and paintings taken as a whole might have a similar quality—less the page by page re-telling of the story than imagery akin to film footage thrown up in an editing room, where it’s both the screen story and a shimmering scan of almost random incident and sensation.

You could almost construct a different picture (or novel) out of it; and it’s not surprising that many of Zak’s more recent paintings—and really most of his work going back as far as 2004-05 seem to offer themselves up to spatial, pictorial, and narrative variations. It was actually quite a while before I caught up with another series that (I’m only guessing) may have been at least indirectly inspired by the world of micro-fantasies that seem to spontaneously explode throughout Pynchon’s sprawling narrative—even when one of those images made it to Artillery’s cover. By that time, Zak had pretty much captivated most of the people who write about art in Los Angeles. But, as I was only just learning at the time, Zak’s life had begun to change long before that cover. Out of an early and more or less constant fascination with girls in music, dance and strip clubs and variously random and deliberated social—and sexual—encounters with them, Zak had himself, no less randomly, crossed over into one of the many image-making domains of the ‘naked girl business’ (as he dubbed it at the time). It was a transition he might have drawn himself into (as, in one way or another, he eventually did)—as if falling out of one frame into another, landing him squarely on a porn shoot set.

You could almost construct a different picture (or novel) out of it; and it’s not surprising that many of Zak’s more recent paintings—and really most of his work going back as far as 2004-05 seem to offer themselves up to spatial, pictorial, and narrative variations. It was actually quite a while before I caught up with another series that (I’m only guessing) may have been at least indirectly inspired by the world of micro-fantasies that seem to spontaneously explode throughout Pynchon’s sprawling narrative—even when one of those images made it to Artillery’s cover. By that time, Zak had pretty much captivated most of the people who write about art in Los Angeles. But, as I was only just learning at the time, Zak’s life had begun to change long before that cover. Out of an early and more or less constant fascination with girls in music, dance and strip clubs and variously random and deliberated social—and sexual—encounters with them, Zak had himself, no less randomly, crossed over into one of the many image-making domains of the ‘naked girl business’ (as he dubbed it at the time). It was a transition he might have drawn himself into (as, in one way or another, he eventually did)—as if falling out of one frame into another, landing him squarely on a porn shoot set.

“Discarding first one tarot, then another, I find myself with few cards in my hand. The Knight of Swords, the Hermit, the Juggler are still me as I have imagined myself from time to time, while I remain seated, driving the pen up and down the page. Along paths of ink the warrior impetuosity of youth gallops away, the existential anxiety, the energy of the adventure spent in a slaughter of erasures and crumpled paper. And in the card that follows I find myself in the dress of an old monk, isolated for years in his cell, a bookworm searching by the lantern’s light for a knowledge forgotten among footnotes and index references. Perhaps the moment has come to admit that only tarot number one honestly depicts what I have succeeded in being: a juggler, or conjurer, who arranges on a stand at a fair a certain number of objects and, shifting them, connecting them, interchanging them, achieves a certain number of effects.”

Italo Calvino, The Castle of Crossed Destinies

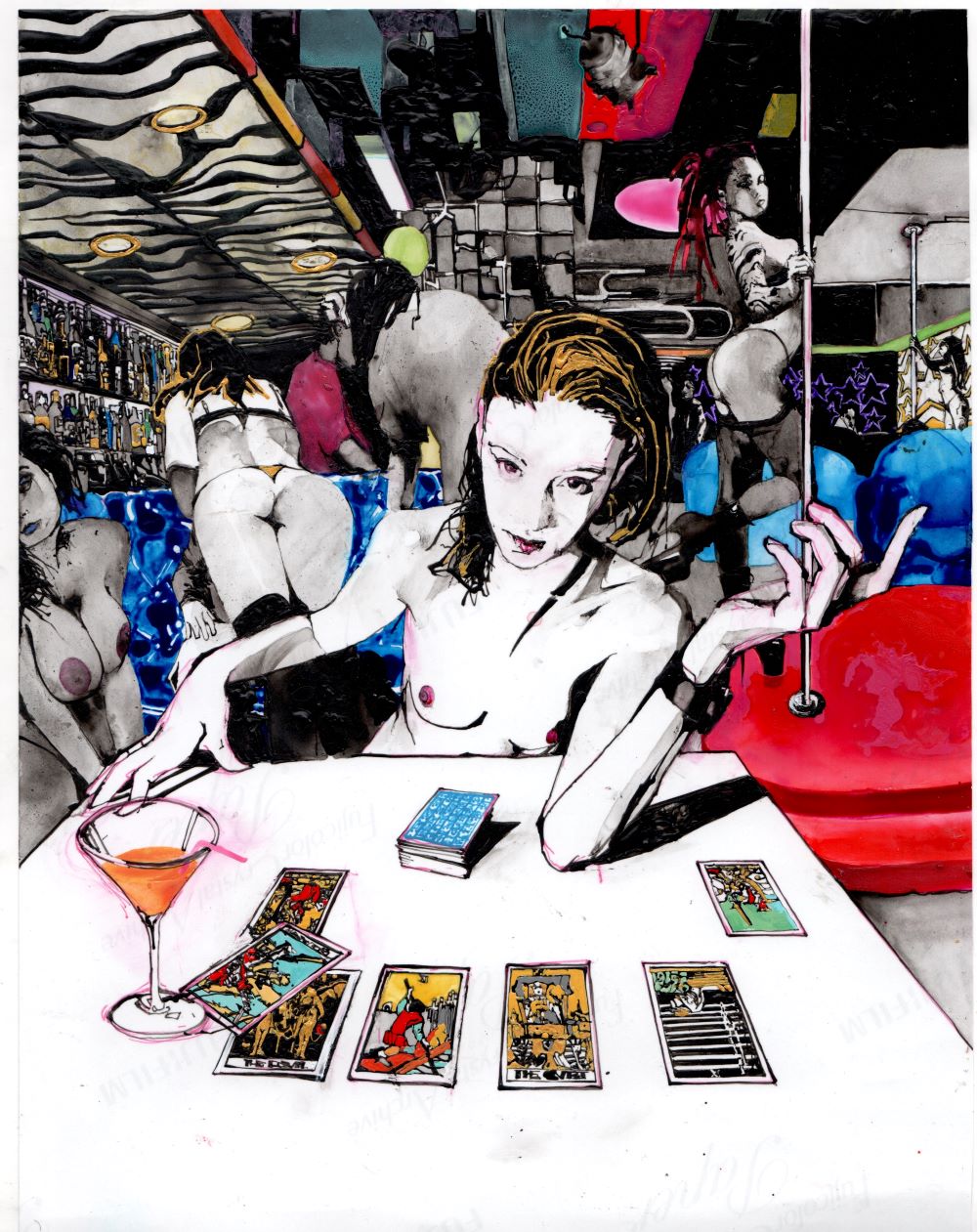

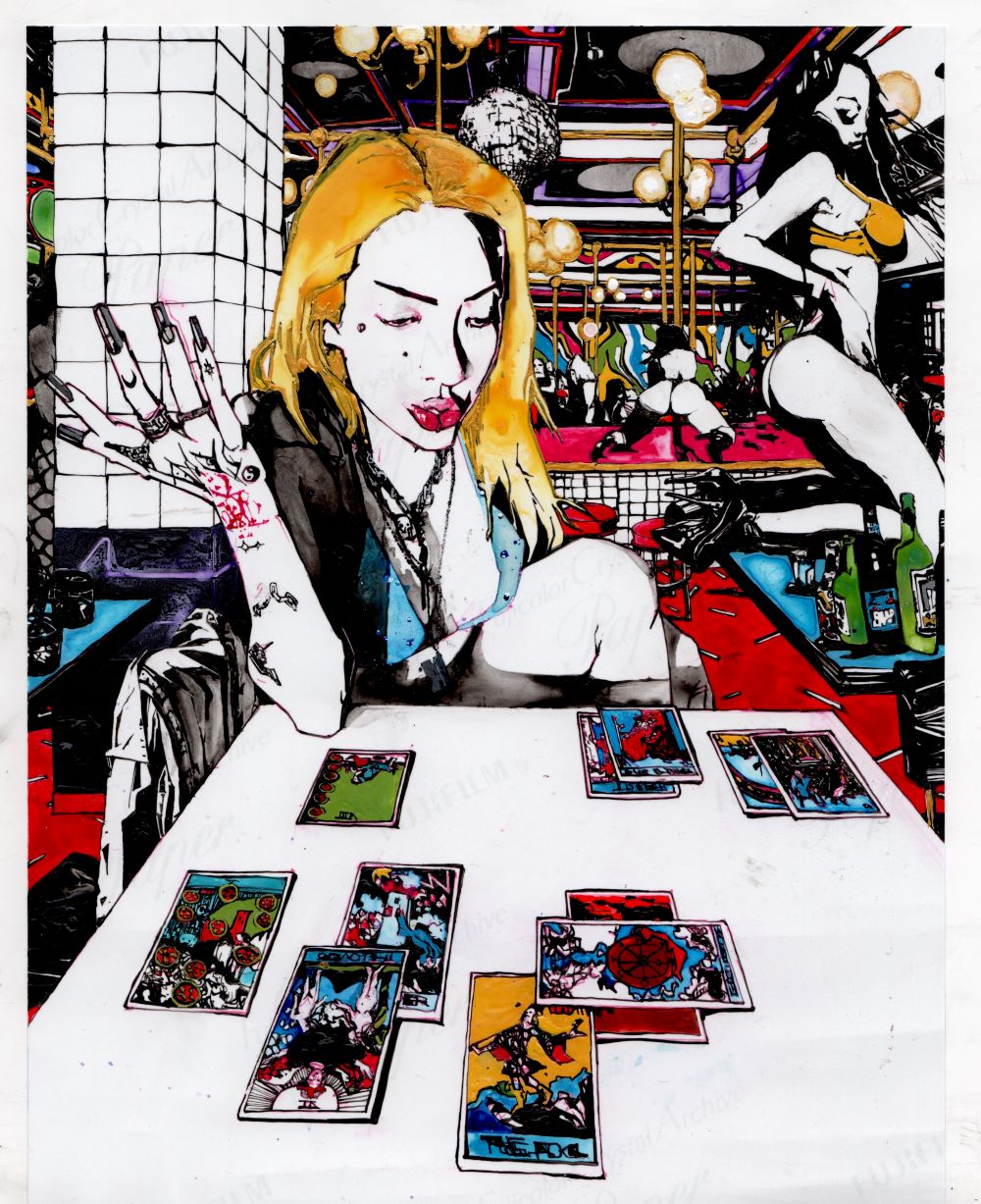

Zak Smith, “Susie Predicts Tribulations Will End Partially Due To A Support System of Strippers and Porn Actresses” (2022)

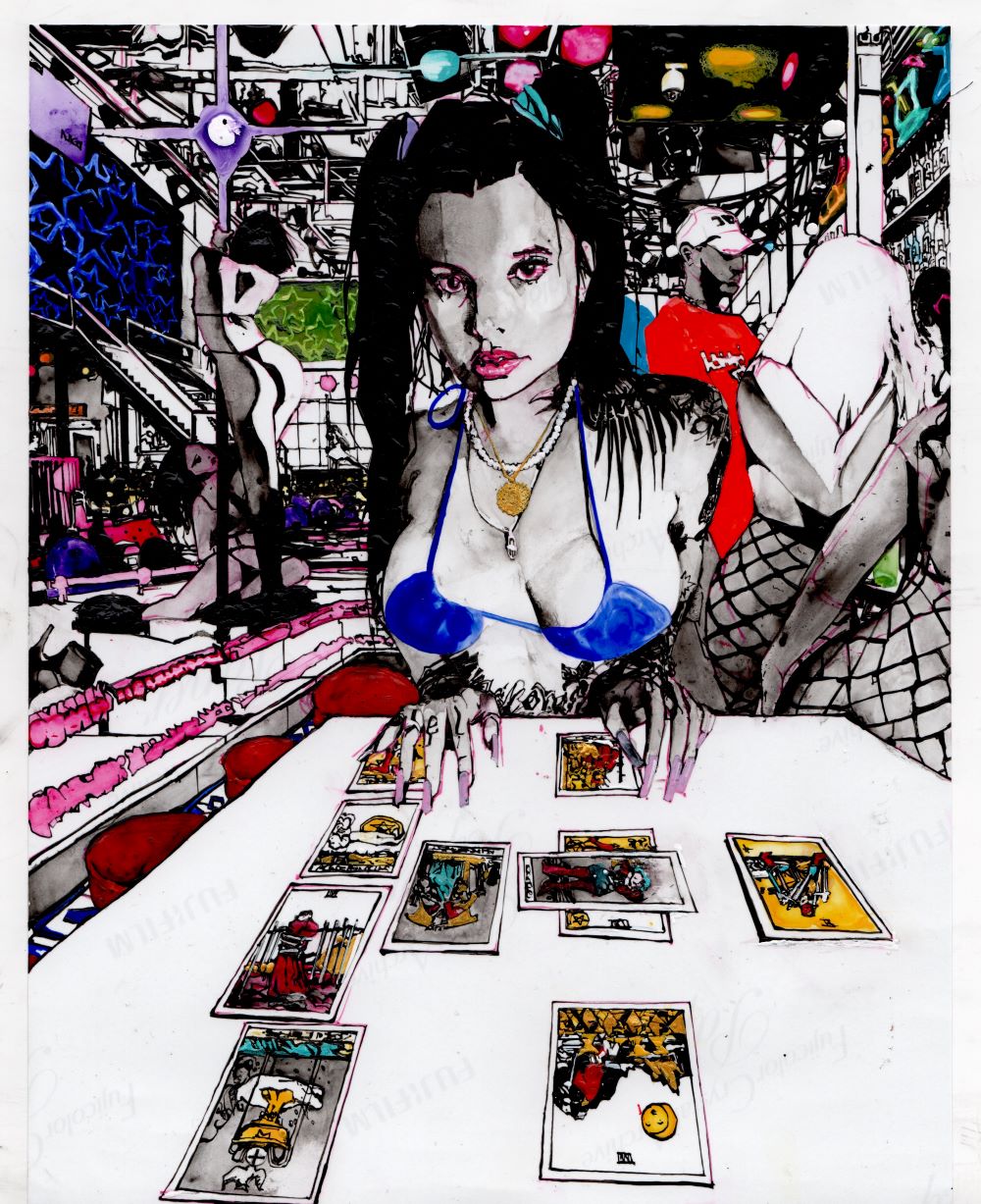

On a recent visit to Zak Smith’s studio, I was struck by a couple of recent paintings on paper. At the center of interiors that seem to approximate the back-bar or ‘back-stage’ area of a strip club or bar, dancer-strippers (presumably taking a breather from the front-of-the-bar action) sit at tables laying out decks of tarot cards. The scenes are variously what we would expect. Behind one dancer laying out a kind of tarot solitaire, we have a rear view of a dancer hoisting herself onto a bar-runway platform as seated patrons in newsboy or trucker caps gaze (seemingly with a slight reticence) into their drinks or towards the dancer’s spectacular anatomy. In another, the dancer seems to engage an unseen companion across the table in what might be a tarot card reading. To her right, only a few feet behind her, a dancer leans at a 45-degree angle over a blue banquette, a customer’s hand poised a discreet distance from her high-booted thigh, while another slightly more clothed figure attends to more mundane business. On the other side of the bar, just over the card-reader’s left shoulder, amid other banquettes, other dancers position themselves at shiny poles on their red-carpeted platforms, ready to playfully, provocatively shimmy, splay and spiral around them—childhood barre exercise ‘rond des jambes’ turned to Möbius strips with points of maximum return.

Zak’s work is all about intricate juxtapositions, though not always so straightforwardly laid out. Also strategies and stratagems—sometimes lost in a mosaic of feints, snares and traps, seeming lost in flickering luminescence and shadow, strobed, or picked out with a baby-spot—orchestrated on the artist’s terms but disclosed in a kind of conversation with the work’s viewer and, to one extent or another, his subjects. The first of these strikes a slightly neutral, introspective note amid a cacophony of distractions; the second, seemingly poised to turn over a fresh card, engages the viewer (or conceivably, a customer) more directly, her level gaze sizing us up frankly beneath a flipped-over shock of scotch-colored hair. I don’t know much about the Tarot (there are more than a few variations on the standard deck), much less its cartomantic readings or predictions. But I keep going back to the cards as they appear here—with the raven-haired dancer turning one row of cards towards the viewer, with her fingers on one of the picture cards (Prince or Magician—I can’t really tell); in the second, the dancer-dealer seeming to wait on our reading with her half-finished Negroni—a 10 of swords next to a Devil. Except as with most of the picture cards, the number is given in Roman numerals (with a Brueghel-ian figure appearing to punt up a stream)—and that number is ‘XII’.

It is said that a 10 of Swords represents “finality”; a point of “no turning back”; the definitive end of one thing and a signal to move on. Yet there’s an entire row—a table—of cards here, each card a door to a specific assignation, a multi-chambered vessel to carry the bearer to innumerable destinations.

I have to assume (or at least guess) that Zak has opened many of these doors—in clubs, hotels, all the porn film sets, stages and locations his work in that industry has taken him, in studios—both his own and those of artist-friends, even his own home. Which is why this ‘Tarot’ series has a double fascination. A Tarot pack or cartomantic reading is as much the subject-player presented with the choice of her/his/their own fortune and navigating—narrating—her/his/their way through it. Also a role—will the player be traveling as monk or midnight rambler, jongleur or judge—or that roving paladin, a chevalier d’epée? What about the tools, the signs and signatures? It’s easy to see how Zak (always a fan and player of games of all kinds) segued from porn performance to the world of game design, especially role-playing games.

Games are all about movement, placement, implicit or explicit bets. For all of the AI-robotic chess adversaries pushing their human opponents to their limits and occasionally besting them, I don’t see non-living, mortal players being easily displaced by AI OS ‘ghost-in-machine’ competitors. There’s a reason we refer to a recorded performance or even the performance space as ‘live’, that we take the sound ‘level’ of a room or its atmospherics. The physically actualized moment, the atmosphere, the inter-personal psychology, the ‘hunch’ is something hard to resynthesize. Notwithstanding the stillness that may inevitably envelop an image, a work or object of art—something that stops the eye, stops us where we’re standing. Duchamp thought of chess as a potentially ideal art form in its aspect of continuous movement and rearrangement of space (grid notwithstanding), yet was scarcely unaware of the eye-stopping moment of ‘illumination’.

Setting games—or cartomancy—to one side, Zak has a fine grasp of both aspects of this equilibrium in the visual arts. (The book he created a couple years back, Things At the Museum with illustrations of museum art works accompanied by his own witty and insightful pastiched ‘guidebook’-style text was a brilliant demonstration of this.) Not long after his appearance in the 2004 Whitney Biennial, a conversation with Whitney adjunct curator (and one of that Biennial’s curators), Shamim Momin, for a subsequent show of collected paintings (Pictures of Girls), elicited both facets of this far-from-linear-narrative dynamic. On one hand Zak acknowledged the speed and fluidity of his process. “… [Y]ou make a thousand choices per minute when you work the way I do.” Yet, prefacing his remarks about the images and the potential narrative around some of them (clearly some distance from the specificity of some of the imagery from Pictures of What Happens on Each Page of Thomas Pynchon’s Novel Gravity’s Rainbow): “I’ve always thought that any ‘story’ comes after the work. … I don’t think of a story and do it. I like what Francis Bacon called ‘the starkness of the image.’ It’s an image—you say to yourself, ‘This really gets to me,’ and then you can … figure [it] out. But that always comes second.”

This is something Zak has in common with any number of artists, designers, and creatives—people spinning a million ideas seemingly moving at the speed of light. The ideas and images swirl and rush headlong, and then, just as the flow approaches warp speed—stop—and another universe unfolds. So it’s not exactly surprising Zak has quite a few fans among similarly creative peers—some well-established, others freshly emerging. There’s a bit of blur and overlap here. Most of his peers have some awareness of his work in porn and game design as well as the fine art domain; but as the mid-20th century Hollywood film director and producer Joseph Mankiewicz once put it, ‘people will talk’…. They definitely have—Smith is the kind of artist you expect to hear has been undone by allegations of sexual impropriety and it’s certainly been tried. He’s successfully sued for defamation three times over the same claims—in LA, Australia and New Zealand—and hasn’t lost a case yet.

While at Zak’s studio, my eye fell on a number of other drawings and studies—clearly work in progress, but with detail and specificity that clearly marked them as portraits, or work that would eventually take shape into full-blown portraiture. One of them was of the artist, Emma Webster, who only three years ago had something of a break-out show at the Diane Rosenstein Gallery in Hollywood. Not too many years prior to that, and not unlike many artists, Webster had done a bit of everything from billboards to theatrical set design, which at a certain point involved working with miniaturized elements or maquettes. In graduate school at Yale (where Zak also did his MFA), she began to experiment with digital scans and modelling using various programs—which pushed her work in a myriad of fresh directions (or conceivably, dimensions). Between fantastic landscape, careering architecture, and games in the virtual sphere, I could see where there might be some connection. I looked her up.

“I was already a huge fan.” That is to say, even before her undergraduate stint at Stanford—aware of his published work and having seen his work at SFMOMA (one of a series of shows curated by Joshua Shirkey for the museum introducing the work of various North American artists). “I’d already thought a lot about his work much earlier on, but … when we first started hanging out in L.A., we talked about painting on a more level footing. I was so fascinated by his process, taking directly from photography—very different from my own process, which has more to do with computer photo-renderings—but with so much spontaneity, connecting with the back architecture of photography.”

Of course Webster was familiar with Zak’s game design activities, but her comments surprised me a bit—and they seemed to dovetail with her specific observations of his portraiture process. “What’s interesting about Dungeons & Dragons is that it’s all about narrative, not as much as how the characters move—the episodic aspect is so linked to the story-telling, which is linked to whoever is in the scene. My interest is more in the architecture of the space; and Zak’s very interested in the quirkiness of the characters—the people or the elves.”

As Zak sketched and photographed during a prep session for his portrait of her, Webster took note of “the way he noticed everything interesting through the mess and chaos of [the studio]; and he’s so athletic about it. He wanted to be sure certain things were in the portrait. He tries to incorporate chaos as a kind of prop. He gets into the weeds, into the dust-bunnies on a level that most people try to avoid.”

It was interesting to hear in light of my own recent conversations with Zak about his own approach to architecture—actual and virtual—of spaces depicted, recomposed or synthesized in his paintings, both old and new. On a certain generic level, we might refer to this simply as an architecture of the demi-monde. But Zak seems to be reaching for something far more ambitious and, well, sophisticated—an architecture of chaos.

In recent years, this has seemed more the province of biologists and climatologists, but as anyone with a passing familiarity with the front pages of the leading metro dailies (to say nothing of broadcast, cable and streaming outlets) could tell you, social, economic, cultural and political spheres are far from immune. And here’s another thing—even viewed through a very downtown/Brooklyn, alt-punk, death-metal, strip bar/sex club lens—before he even really arrived there—Zak could see it all coming.

Consider this tidbit:

“Antifacts were manufactured until every truth had a twin across the line of scrimmage. Entirely alternate realities were posed and men and women were bribed into talking them into being….”

Or further on, in some proximity to this passage—

“A great trade in openly pseudodemocratic TV shows arose, where vast voting audiences eagerly waited for the weekly results of talent contents between warring morons that viewers doubted they’d actually participated in. These offered the thrill of dinging yourself a victim of electoral fraud without the disappointment of realizing it might matter.”

These are from a chapter of his 2009 memoir, We Did Porn; but you could almost open the book randomly and find similarly diamond-brilliant observations or reflections on any page.

“I haven’t actually read his memoir yet.” I was talking with Swoon—which is both the artist, Caledonia Curry’s professional name, and the name of her studio (as most readers will be aware, a number of her projects are fairly large-scale team efforts). “I think in a way maybe everyone thinks they’re an outsider. I think some people are more outsiders than others, making their own paths. And I think Zak really has that and that’s one of the things we tend to chat about.”

L.A. audiences may be more familiar with Swoon from her participation in Jeffrey Deitch’s 2011 MoCA extravaganza, Art In the Streets. But for some of us, she had already made a ‘bigger splash’ (so to speak), with her Oldenburg/van Bruggen-scale invasion of the 2009 Venice Biennale by way of a parade of her trademark junk rafts making their way through the Grand Canal—really the culmination of a number of similar projects executed with Deitch Projects’ sponsorship. For a number of critics (including New York Magazine/Vox critic, Jerry Saltz), the Swimming Cities of Serenissima eclipsed almost everything else exhibited at the Biennale.

“The big thing that stands out for me as far as the interconnection between my work and Zak’s is that we’re from a generation that came up in the shadow of this kind of Conceptual generation. There was this sense that aesthetics were finished, that everything in painting had already happened before people came in with Minimalism and Conceptualism.

“When I started to draw, I almost thought it was slightly taboo. Or that my elders wouldn’t respect me. And I had this belief that we could kind of reinvent this space to draw and depict our world, and that a new sensibility could emerge. I perceived Zak being part of that same initial push—that this was a new era and we believe we can draw that new era.

“Depiction isn’t dead and this ability to look and draw and see and feel and really be in the mix with life remains relevant no matter what other media or what other modes of working are available to us.”

Zak Smith, “Brante Predicting We’ll Have Sex A Lot, Go To Portugal, and I Will Have My Shoes Stolen in Japan” (2022)

But that “mix with life” can be a very tricky business. It’s what frequently has us going a ‘thousand choices per minute’. We make those choices and those choices change us—and reveal us to ourselves. At one point in his 2006 conversation with Momin, Zak makes reference to an observation of Martin Amis’s about one’s “talent or taste” knowing “more about your subject than you do.” Momin extrapolates on this a bit, commenting, “The idea of things being made that know more about you than you do is exactly right, it’s more about the viewer, too, about what you’re engaging and why…” This, one thinks (not unlike Momin), is what all good art does. But the ‘second’ sight, certainly the insight, comes after the sometimes fraught moments of actual making. Zak talks about this a bit in We Did Porn—with unguarded, even brutal honesty.

“My drawings are often people, and they’re by and large not me. So they are social. But I am not so social, really, though I can put up a great fucking front. We can all put together a great fucking front, because we all have our reasons.”

But the ‘fronts’ change and so do the reasons, the rationales. There are contradictions and complications, there is confusion, there is consideration and reconsideration; and it always shows up—and not just in the art. Zak has seen this unfold in life as well as well as the studio—in the clubs, bars, porn sets, and other places public and private. He goes in for the deep dive, the cliff’s edge jump, and it can be bruising.

It helps, as we’ve rediscovered in the years since Zak’s prescient memoir, to have the truth on your side; and we see that in his portraiture—and all his art. It’s not just the architecture, the orchestration. It’s about looking closely and parsing the truth about a person’s reality. Webster described part of his approach to portraiture. “When he came to my studio, he was just looking at everything. He wants to see you in your space, in your house, while you’re working. He must have taken a thousand different photos. He’d look at something and say, ‘That object is so strange, it could only belong to you—so that belongs in the painting.’ Any portrait is personal. His are hyper-personal.”

Zak still takes the deep dive. “I think I should probably say a thing or two about the drawings. I keep making them. I do all these things and sometimes sit and draw during them and sometimes draw them later.”

You open one door and you close another. You take a card and place your bet. (Yeah, maybe you sip a drink as you consider it.) You take another. You play your hand. The odds are never exactly in your favor. But—we keep our eyes open—there’s always magic to be made and to behold.

Zak Smith, “Yams Predicting Success and Escape from Confinement After Legal Tribulation” (2022)

An Unburnt Witch: Zak Smith Drawings will be on view through May 6, 2023 at the Torrance Art Museum — 3320 Civic Center Drive, Torrance 90503.