In visiting Yasmine Nasser Diaz’ show, “soft powers” at Ochi Projects, I had the rich pleasure of speaking with the artist about her process, intimate spaces and how soft powers are not only a cause for hope, but are—and always have been—a female superpower.

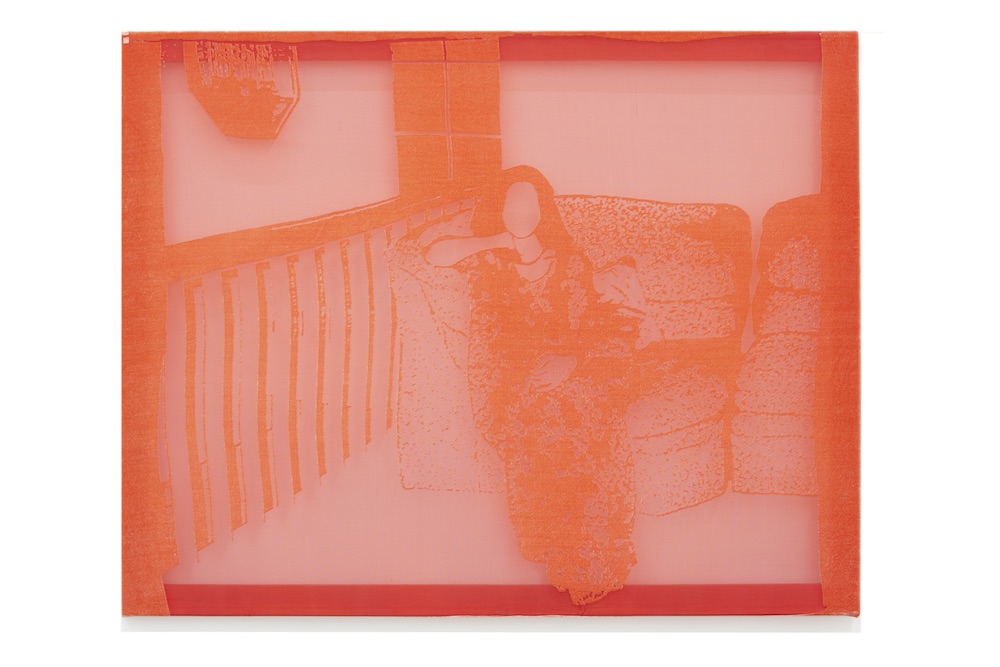

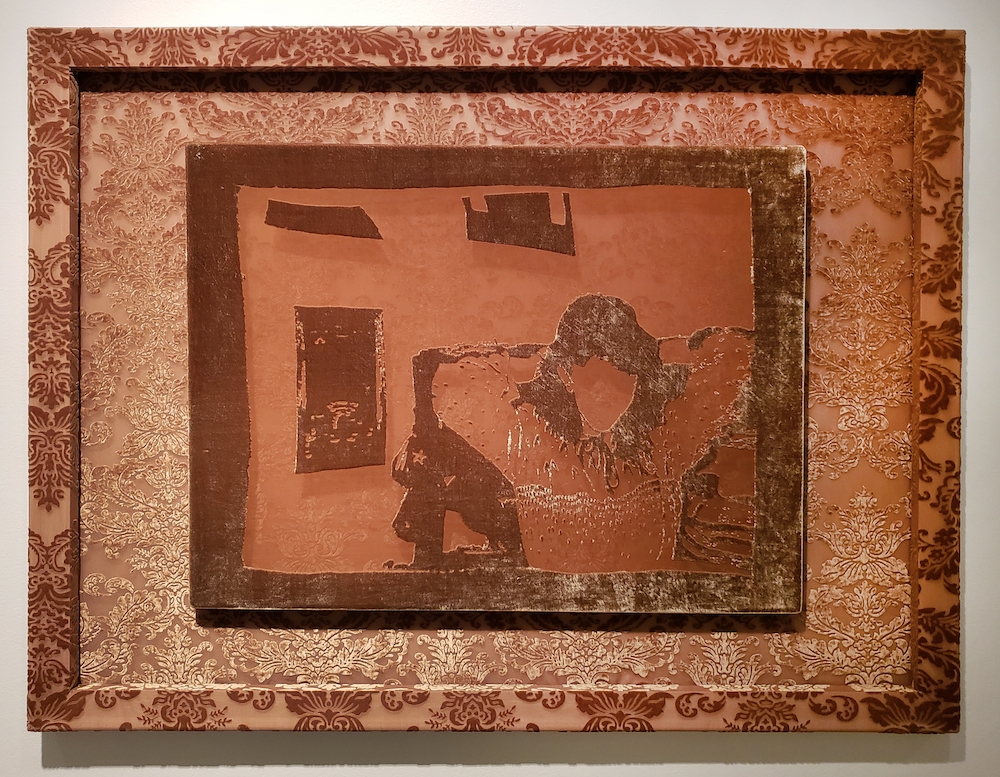

“Soft powers” is a breathtaking series of fiber etchings on velvet-patterned jewel tones, resplendent pearls, and ebonies—the images sourced from Diaz’ personal archive and collected from Yemeni-American girls she knew in her native Chicago. Diaz works with the images manipulating silkscreen stencils and then employs a burnout technique where the mixed-fiber material undergoes a chemical process to dissolve the cellulose fibers, revealing a semi-transparent pattern against the more solidly woven fabric. Burnout fabric—fashionable in the ‘90s—dates back to 19th-century France in Lyon, and served then as a less expensive, but still opulent, alternative to lace. Diaz explained that its proper name, devoré, is rooted in the French verb dévorer: to devour. As she detailed the intricate work of shaving tiny bits of velvet to trace the photographs, I felt the acute satisfaction found in redirecting destructive forces as an avenue toward beauty and preservation.

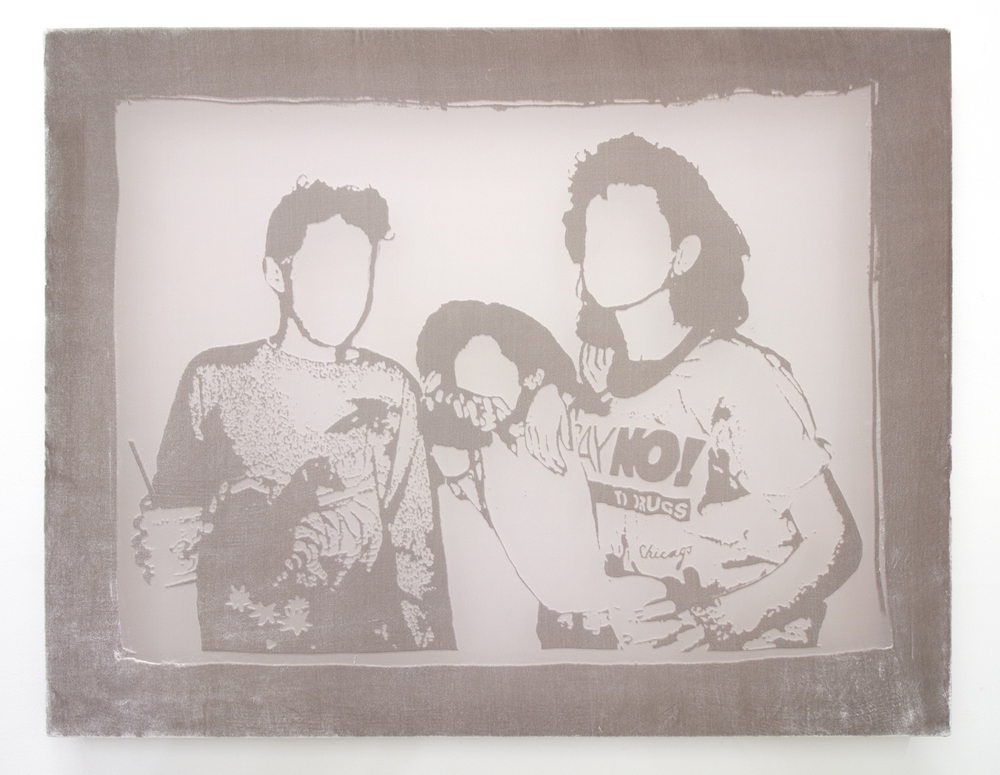

Yasmine Nasser Diaz, Say No To Drugs, 2020. Courtesy of Ochi Projects.

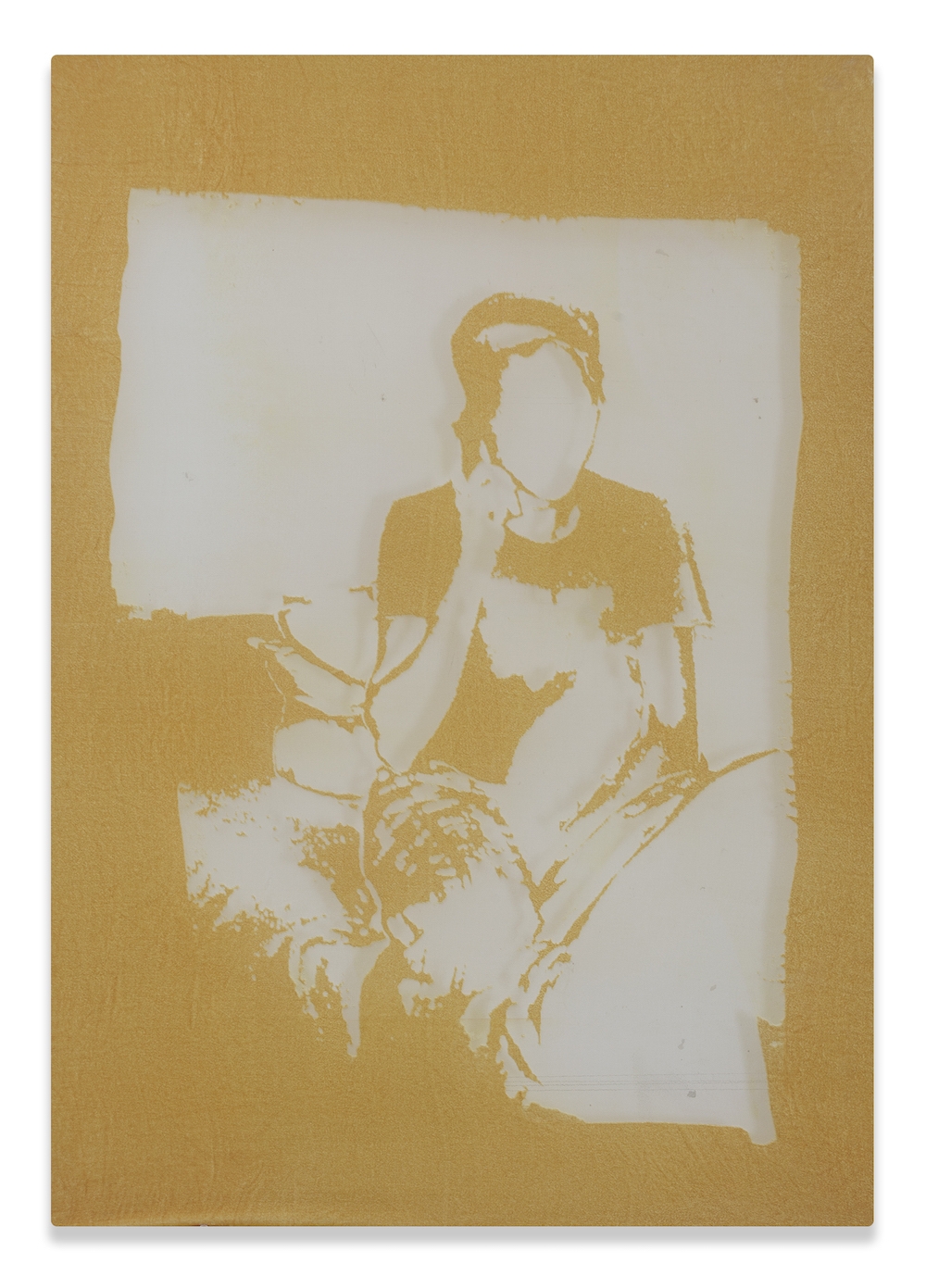

Each work in “soft powers” is mysterious and alluring in its own right, offering the same pleasure in discovery one experiences thumbing through antique film negatives at a flea market. With the facial features scraped away and blanched out, the viewer seeks not to identify who the figure is, but what she is doing. The nature of the burnout velvet allows Diaz to favor outlines and shadows so that we are drawn toward the position of a girl’s hands resting on her lap, or the way she holds her best friend around the waist. If in the original photograph their cheeks were pressed together as they embraced, in the etching, their cheeks now appear to merge—the devoré fabric allowing sisterly care to look how it feels.

Yasmine Nasser Diaz, On Hold, 2020. Courtesy of Ochi Projects.

Silkscreen stencils can conjure references to guerrilla art and punk rock, yet the use of velvet in the chosen color palette gives Diaz’ work an anachronistic charge. Burnout was not only popular in the ‘90s dELiA*s catalog, but used in dir’oo—a style of dress worn by engaged and married Yemeni women. Diaz explained that her mother was drawn to these shades in rich plums and burgundies, despite their colors not being traditionally found in Yemen; the jewel-toned palette speaks to hybrid culture in Diaz’ neighborhood, a mix of SWANA and Yemeni people. Although the shades undermine Yemeni authenticity, they clue us into the dynamism of third-culture identity.

Yasmine Nasser Diaz, Graduation Day, 2020. Courtesy of Ochi Projects.

According to Diaz, “soft powers’” premise of “attraction rather than coercion”—is something innate to feminity. The term encompasses the cultural code-switching familiar to children of immigrant parents; it is never articulated that this is what you do, but is born from watching closely those around you. When Diaz stressed to me the importance of showing girls existing in their own spaces; that being in each other’s rooms afforded a retreat from the feeling of being hyper-surveilled and judged by family and the world, I realized it would be a misreading of her work to see these rooms as spaces of confinement; these are spaces where multiple identities can coexist and flourish. In these teen spaces, now nostalgic, where our friends felt like magical beings who might usher us into our next iteration, where the objects inside are imbued with emotion and experience, watching is reimagined. Close-looking occurs not to monitor and control the girls, but to delight in and celebrate them—girls look to each other and wonder at how she dresses, how she wears her hair, what tape is playing in the boom box. I told Diaz I felt she beautifully honored the “girl gaze”—the gawking impulse to admire, adore and document: Didn’t we all have an older girl who was a demigod to us? Who taught us how to dance? Who we’d mimic to the point of embarrassment? Diaz smiled and drew my attention to a tiny poster of the indie band Sebadoh in one of the works, explaining, “I kept that in the image because my sister was obsessed with them, and so, of course, I was too.”

Yasmine Diaz Portrait. Courtesy of Ochi Projects.

Diaz’ etchings were born out of her collage practice; what began with wanting to incorporate fabric onto the collages soon became working entirely with the textile. While the allure of collage is in the snipping away of images to serve a precise and controlled impression, burnout is fussy and unpredictable. Once she’s begun the chemical process, she must work quickly, and despite her intention and precision with stenciling, “when I begin etching, I realize the velvet will do what the velvet wants to do,” she said.

Yasmine Nasser Diaz, Thick as Thieves, 2020. Courtesy of Ochi Projects.

In my favorite piece in the show, three young women pose together for the camera. By the tilt of their heads, we know they are playful. Their bodies merge like a mountain range, the particulars of each arm trailing off, melting like amber. According to Diaz, the velvet did what it wanted, and she was pleasantly surprised with how it evolved. As we moved through the show, Yasmine would hold up her phone, using the flashlight function to illuminate the pieces. She was gracious and inviting, and when I looked where she did, the background textile would sparkle through the velvet that had been scraped away: a girl’s peasant blouse was now flecked with gold dust, a curlicue of a landline snaking down a breastbone appeared 3D, taking on the sensual pleasure of a shadow box

In trusting that the velvet will do what it will do, in going towards the spaces and women she loved, Yasmine Nasser Diaz offers us a retreat to a space where watching is not about surveillance, but about care, where we can be invited into feminine space and leave astonished.