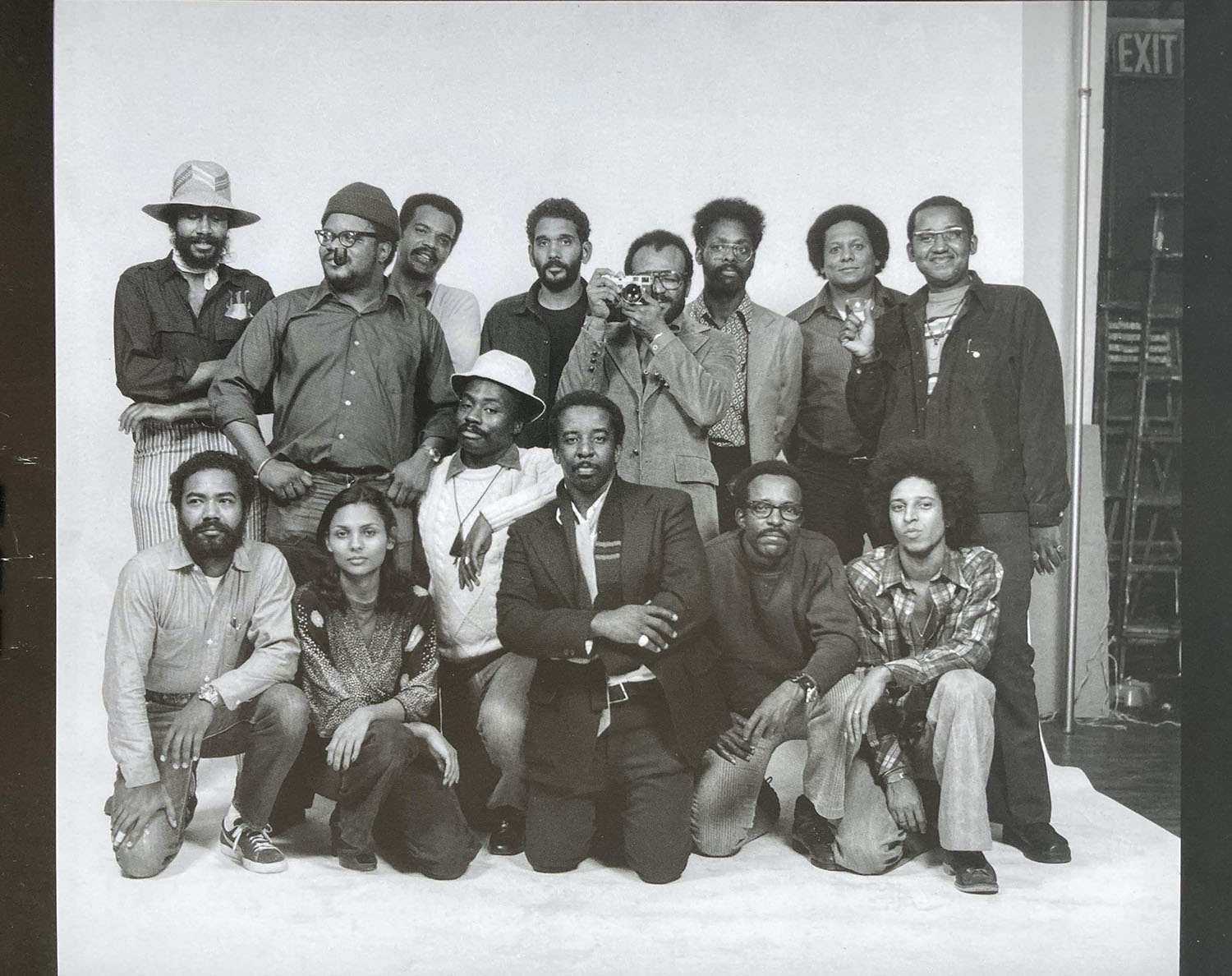

“Working Together: Louis Draper and the Kamoigne Workshop” is a photography exhibition on view at the Getty Museum that chronicles the history of an extraordinary partnership of Black photographers.

Founded in 1972 by Louis Draper, the Kamoigne Workshop was a collaborative comprising African-American photographers. Draper is singled out in the exhibition’s title because he was the founder of the workshop who was able not only to supervise all his colleagues, but to assign to each the project best suited to his talents. He characterized the world in which they were all living as having the room—and a need—for them to work together. Their home base was Harlem, a place that Draper described as “Hot breath streaming from black tenements, frustrated window panes reflecting the eyes of the sun, breathing musical songs of the living.” His urgent view of the workshop’s mission was not just an exclamation but an inspiration.

“Kamoigne” is word drawn from Kikuyu, a native language of Kenya. Literally translated, the word means “a group of people acting together.” At the end of the workshop’s first year, an annual portfolio was published, which became a tradition. One of these even caught the attention of Henri Cartier Bresson, a photographer who had also been a founder of the co-operative for photographers called Magnum. The influence both he and Magnum had on the Kamoinge photographers can be seen here and there in mid-1960s photographs by Draper and some of the others.

Herman Howard (American, 1942-1980), New York, ca. 1960’s. Collection of Herb Robinson. Courtesy Getty Center.

That said, Draper and the members of the workshop all stayed close to home with photography of life as lived by Blacks. Their work (mainly black-and-white prints) ranged from candid shots of the ever-flowing life on the streets to the stilled presence of a portrait photograph. But despite the success that Draper had earning the trust and rewarding the ambition of the workshop’s members, there was one prominent exception—Roy DeCarva.

DeCarava had been the most productive member of the workshop after Draper himself in the early days, so Draper tried hard to talk him out of his resignation. But DeCarava wouldn’t budge. The reason was that being a reporter with a camera didn’t permit him to fulfill his true ambition, which was to be an artist. Though he and Draper remained friends, DeCarava became the widely respected and inventive artist he had always dreamed of being.

Over time the purpose of the Kamoinge Workshop shifted. In 1992, a new generation with different backgrounds were enlarging the way photography was represented. While Draper remained a force in the organization he had founded, he also yielded recognition to this new generation whose members were college-educated and whose goals were more aesthetic than editorial. One result was that the word “workshop” was dropped from the organization’s name. By then, Draper’s own work in the medium had expanded in ways that encouraged him to welcome what the organization he had founded was to be called.

0 Comments