Kim Abeles’ studio doesn’t have enough chairs, so we have to sit in the adjacent gallery space at the front entrance of the building. Even though it’s glaringly sunny outside, it’s freezing inside the space as attendees spill into the room and sit down on rolling office chairs, stools, wood blocks and ledges. This is a meeting of the Association of Hysteric Curators, a self-described “fluid Los Angeles-based trans-generational group of feminists dedicated to cultural discussions around contemporary feminist issues in a non-hierarchical structure.”

AHC meeting at Kim Abeles’ studio

Art tends to reflect life. In a reality where blatantly sexist politicians gain office, where women continue to earn less than men at 80 cents per dollar, and still have to fight for the same reproductive rights that their grandmothers experienced, the art world fares no better. The facts are everywhere: 28 percent of museum solo exhibitions spotlight women; only 7 percent of works on display at New York’s MoMA are by women; only 4 percent of the Met’s exhibitions are by women artists. Collectives like the aforementioned Association of Hysteric Curators (AHC) aim to serve as a jumping-off point for women navigating the sexist waters of the art world.

Los Angeles artist Mary Anna Pomonis created AHC in 2014 after corresponding with an art museum curator. She had been asked to participate in an international exhibition, but was rejected after submitting her work on the grounds that it was “too personal.” Her aim had been to use the loss of expressive mark-making in her work as an act of resistance against her art school education, and sought to make an act of resistance out of something personal. While she argued that the personal—as feminist author Carol Hanisch famously stated—was political, the curator would only budge so far as to allow Pomonis to curate a group art show under her concept, insisting that her work was too “soft” for the more overtly political show. Her frustration and anger over this passive-aggressive rejection turned to action and, alongside artist and longtime friend Allison Stewart, she set out to create a collective curatorial board that would highlight the work of women and assist them in navigating the LA art world.

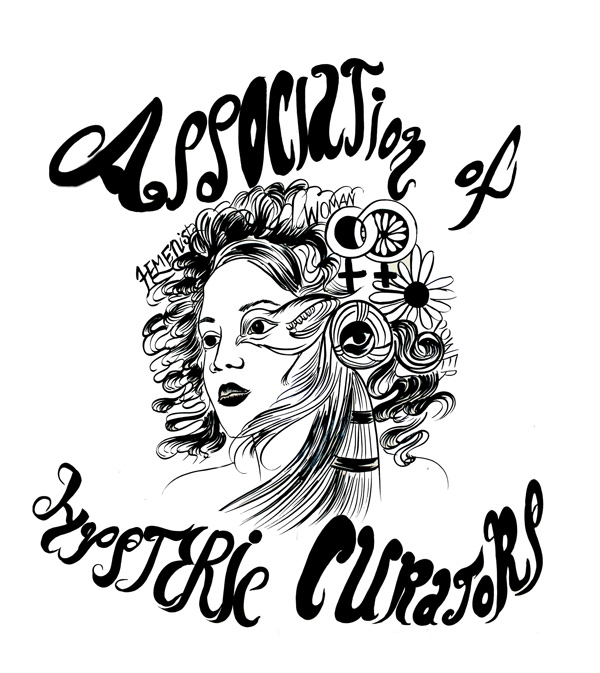

There was controversy and internal conflict from the beginning. The group lost about a quarter of its members over naming themselves the Association of Hysteric Curators—a decision sealed by a member who stated that her husband would never attend a show put on by a group with such a name.

Mary Anna Pomonis and Allison Stewart at The Collectivists, Brand Library, photo by Simeon Soffer

While I feared encountering a culturally homogenous group of women at the AHC meeting, I was pleasantly surprised by the varied ages of the women present (the number of people of color was a different story). This mixing of generations is not an accident, as Pomonis explained, “We think it’s important to be multi-generational, so that the older generations can remember what it’s like to be fresh out of art school and entering the art world, and younger generations can learn from the older generations present.” Members and newcomers squeeze into the cold, bare room with a large painting of angel wings in the corner, and begin to discuss the collective’s upcoming project at Cerritos College: the Far Bazaar. There is one male present and Mary Anna is taking notes.

Lili Bernard as Angela Davis, NOTE: SEE MORE PHOTOS BELOW.

AHC seems to move slowly, yet surely. While they have curated a handful of shows, among them a series of photographs of women that were left out of history books titled “Resurrecting Matilda,” and the exhibition and series of programming “Coming to the Table,” it seems as if their best work is yet to come. Their upcoming curatorial projects are promising, particularly the panel they are holding on the history of feminist collage in Los Angeles. The group itself states that they “understand that democratic consensus is slow and laborious in comparison to the type of fast-paced and often decentralized systems found today. The reduced pace of our methodology allows for ideas to ebb and flow through ongoing conversations aimed at process over product.” While democratic process is fine and good, certain details like having a working website other than a Facebook and barely-managed Tumblr help legitimize collectives speaking for marginalized groups. The statement of “process over product” also implies that we can only choose one—a sentiment echoed throughout the feminist areana.

Pomonis noticed the phenomenon that women often stop making work around the age of 24; often, it seems, because they lack a community of women around them to facilitate commercial gallery shows. When the majority of students enrolled in art school are female, yet the majority of artists showing after art school are male, many women feel discouraged in their post-college practices. Women are frequently pushed to make a choice between work and family, and Pomonis has personally felt lost and discouraged because of art-community backlash over her choice to have a child. The guidance she received from Kim Abeles helped her push through this, and she sought to create the same environment in AHC where younger generations gain knowledge through female artists who have faced similar circumstances.

Association of Hysteric Curators logo

There seems to be a disconnect, however, as the lack of “productivity” of the AHC shields them from being exposed to the exact young women artists that they aim to guide. The group is also admittedly exclusionary, with Pomonis stating that they “prefer to keep the group small” and “have an extensive process for anyone to enter the group.” While small collectives can be effective for decision-making in a democratic format, one has to wonder about the effectiveness of AHC. If the goal is to create a platform for upcoming women artists to stand on, some solutions could include posting resources on a website, having open-house seminars, or essentially any other type of community involvement geared towards young women.

After the meeting and Abeles’ studio visit, we sit (and stand) in her small space, as she explains her process. She ends the visit with the remark that the most important point about surviving in the art world is being true to oneself: “You can give others parts of the work, but if you hand over the essence of yourself and change your work for others, there really is no point in making it in the first place.” The Association of Hysteric Curators seems to be striving to create that space, in whatever ways they can, for women to have a voice and stay honest.

-

Bre-Z as Sojourner Truth

-

Noelle McCleaf as Rachel Carson

-

Marjan Vayghan as Parvin Etesami

-

Allison Stewart as Margaret Skinnider

-

Rachel Finkelstein as Lilith

-

Carole Caroompas as Laskarina Bouboulina

-

Kim Abeles as Joan of Arc

-

Sandra Vista as Florencia Adela Marcus Arqualla

-

Mary Anna Pomonis as Enheduanna

-

Lili Bernard as Angela Davis

Above slide show photos by Mary Anna Pomonis and Allison Stewart.