Abstract Expressionist painting remains one of the most pivotal and enigmatic art movements of the 20th century. Its continued influence on current abstract painting can be seen in the work of the best practitioners such as Albert Oehlen, Yayoi Kusama and Frank Stella. It endures today partly because the artists were able to synthesize essential qualities of modernism from late 19th and early 20th century European art into something that was truly new, achieving the ultimate embodiment of modern painting. Although it dominated contemporary art in the 1940s and 50s, it is known today mainly for the work of a handful of mostly male artists. Fortunately, history is currently being rewritten, as evidenced by the recent stellar exhibition “Women of Abstract Expressionism” at the Palm Springs Art Museum.

The initial impact of the show is startling; the quality and range of the work presented outshines most of the current abstract painting one sees these days in galleries and museums. It is no surprise that Joan Mitchell’s work stands out, since she is one of the best painters of this era, man or woman. Cercanto un Ago (1957), a nearly square, almost 8-foot canvas is abstract painting at its finest—no discernible image, but an emotional overflowing that stops you in your tracks.

Joan Mitchell Untitled 1952-53, Collection of the Joan Mitchell Foundation, New York.

On equal par with Mitchell is Lee Krasner, whose career was overshadowed by her husband Jackson Pollock, whom she was instrumental in guiding and promoting. Krasner possessed an acute understanding of modern painting, having studied with Hans Hofmann, and it shows in the strength of her paintings, which range greatly in style. Charred Landscape (1960) has an affinity with Pollock’s Black Paintings from 1951–53, yet is in no way derivative, and like most of her work looks uniquely her own.

Grace Hartigan is another strong presence in the show, in particular with her large work, The King is Dead (1950). Its overall composition bears close resemblance to Willem de Kooning’s Excavation from the same year. In contrast to de Kooning’s rather achromatic work, Hartigan’s painting is a riot of color, with primaries, plus black and white, which was characteristic of de Stijl, but its sensibility is exactly opposite.

Willem’s wife, Elaine de Kooning, stands out as well, but for the wrong reason—most of her paintings are clearly figurative. While it is true that Abstract Expressionism was never really as abstract as the critics of the day wanted it to be, de Kooning’s are figurative in the most obvious and pedestrian way. Her paintings that fare best here are those that are the most abstract, like the puissant Bullfight (1959), which is one of the most compelling works in the show, with its highly saturated, polychromatic color and tornado of crashing brushwork.

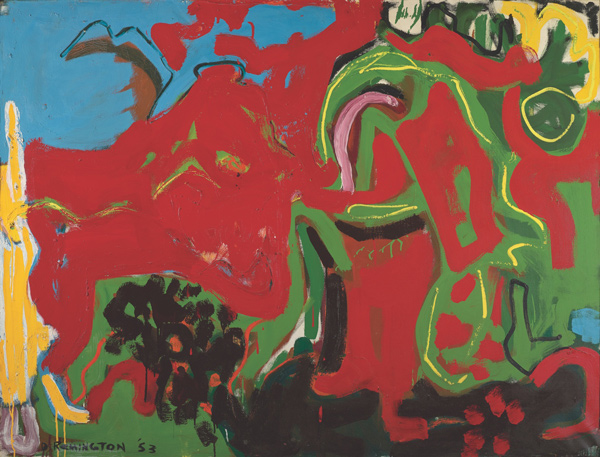

Deborah Remington, Apropos or Untitled, 1953, Denver Art Museum, Courtesy of the Deborah Remington Charitable Trust for the Visual Arts.

The big surprise in the show is the work of several outstanding painters who are mostly unknown today, such as Mary Abbott, Perle Fine, and Deborah Remington. Abbott’s All Green (1954) projects an intoxicating lyricism akin to Miles Davis’ All Blues from his classic modal jazz recording, Kind of Blue, from the same time period. Fine’s distinctive use of undulating branch-like line work distinguishes her from the usual gestural approach seen throughout most of the show. Remington’s Phunky or Dacia (1956) is an enigmatic work sitting right on the edge between abstraction and figuration; it almost anticipates late Philip Guston.

Curator Gwen F. Chanzit described the genesis of the show as being concerned primarily with resurrecting artists from the period that have been overlooked, and it turned out that they were predominantly women. Shows like this one are important in bringing to light artists of quality that have been forgotten by history. It is difficult to imagine today what it must have been like in the 1950s to be a female Abstract Expressionist in an art world overwhelmingly dominated by men.

While today’s art world gender balance can hardly be called equitable, women artists are receiving far more attention than in any other period in history, and it’s about time that artists were judged by the quality of their work, not their gender, age, race, institutional pedigree or any other factor outside the work itself. Then perhaps exhibitions like this one won’t be necessary, and shows can be based upon themes and ideas rather than identity politics, which continues to dominate the national consciousness, perverting notions of quality and ghettoizing creative and human potential.