Right from the start, “Zoe Leonard: Survey,” a career-spanning exhibition organized by the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, establishes the artist’s role as an art-world renegade and provocateur. Now on view at MOCA’s Geffen Contemporary site, the installation begins with a pairing of photography and sculpture in a narrow gallery where Leonard’s photographs made through airplane windows are on a wall opposite a row of suitcases. Just as the photographs are a series of clichés (everybody has taken pictures framed by airplane windows), the suitcases are ready-made objects that become sculpture only by virtue of being displayed in a museum. Cliché is a French term for a photograph. Those on the wall lead to another kind of cliché: stacks of postcards from Niagara Falls. Leonard has also emphasized that her suitcases and postcards are clichés by choosing examples that are decades out of date. Such unaesthetic objects challenge the idea of a museum as a place full of treasures from the past.

The arrangement of the luggage and the photographic images on opposite sides of the gallery establishes a dialectical relationship, as if these two kinds of found objects are vying for attention. But in the next two galleries, some of the photographs take on a dialectic relationship with each other. Two photographs hung near diagonal corners of the second gallery are of mirrors reflecting only a smear of light from a window. And in diagonal corners of the third gallery, two more photographs—one in black and white, the second in monochrome red—depict walls in which a window has been bricked up or covered with metal sheeting. Like the reflections that befuddle us in the mirrors, the interiors we would expect to see through the windows are blocked by an abstract flatness. The dialectic in these pieces is between the work of art and us, the viewers.

Robert (installation view), 2001, 10 suitcases, courtesy Museion Foundation, Bozen, Galleria Raffaella Cortese, Milan, and Collection Enea Righi, Italy.

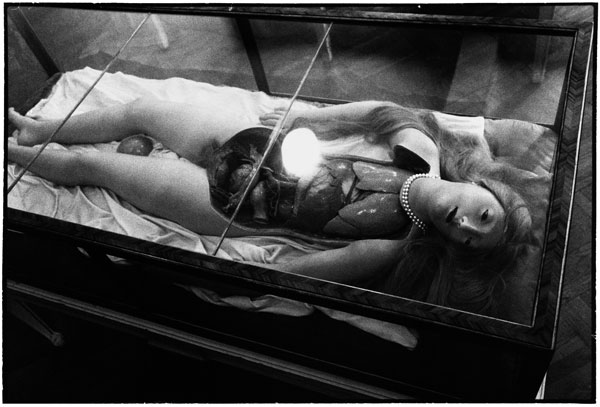

Other images are more transparent. One subject is a cut-away dummy of a woman’s body that reveals all the organs between the neck and the pubic hair. And there is a series of views of a bell jar containing the head of a bearded lady. But the views like these that are obvious seem to me less significant than those that are obdurate, like the obliquely reflective mirrors and blocked windows described above. The visual dead end represented by the windows and the carom-shot of the light off the mirrors strike me as metaphors for the way Leonard’s career as a photographer has rebounded from—bounced off of—an earlier, unquestionably obvious use she made of the medium in the ’80s and early ’90s.

In that fraught time of the AIDS epidemic, Leonard joined ACT UP, the Aids Coalition to Unleash Power, and morphed from being an artist into being an activist. Her mission in life during this period changed so intensely that it wasn’t until later that she and one of her comrades-in-arms, Anna Blume, discovered their equally intense relationship as artist and art historian. (In 1997, a Blume interview with Leonard was published in the catalog for Leonard’s exhibition at the Vienna Secession.) Leonard’s key photographic piece then, which she circulated as a poster, was titled Read My Lips. Made in 1992, it attacked the Supreme Court’s ban on abortion information. The image was a close-up of a vagina, which provoked a public outrage stoked by Leonard’s identity as a woman and a lesbian belonging to the art collectives Gang and Fierce Pussy.

In 1992, Leonard also made variants of the Read My Lips image using different women as models and slightly varying the poses, which were used in installations she made that year for Documenta IX in Kassel, Germany. Her black-and-white photographs were used as interventions in a wing of the Neue Galerie, where they were placed in juxtaposition to, as she has put it, “a lot of very bourgeois portraits of women” painted in the 18th and 19th centuries. It was a gesture that signaled her shift from feminism as a polemical social cause back to the art world. Only one work in the MOCA exhibition reminds us of the stand she took then. It is a 1992 piece consisting of two typed sheets titled “I want a president.” Its first sentence specifies “I want a dyke for president.”

Leonard’s recent work turns away from explicit texts toward the implicit symbolism of art. Her self-consciousness as a woman and a lesbian is now expressed more poignantly—symbolically—in her photographs of trees and, perhaps most powerfully, in a sculpture she has made from an actual tree. In the third gallery, which contains Leonard’s photographs of the impenetrable windows, the first images we come upon are a couple of matched photographs of trees in New York. Though shot in color, the subject is so monochromatic that the prints might at first be mistaken for black and white. Each tree was planted in a patch of dirt on a sidewalk, but the trunk of each has grown beyond its concrete box and the roots have spread beyond the tiny patch of ground to which they were initially confined. In the portraits Leonard has made of them, these trees take on an expansive new life as symbols.

Zoe Leonard, The Fae Richards Photo Archive, 1993-96, (detail), gelatin silver prints and chromogenic prints with typewritten text on paper, dimensions variable, Eileen Harris Norton Collection.

On an adjacent wall halfway around this gallery is a run of four more prints of trees that, while growing, absorbed the strands of barbed-wire or chain-link fencing in which they were imprisoned. Then, a little further into the exhibition, a small gallery off to the side continues the tree motif with compositions that seem a bit over the top in the context of Leonard’s characteristically austere work. Four black-and-white images of underbrush reveal bird nests with eggs in them. Next come two prints in full color of trees in different stages of losing their leaves—images that verge on a Romantic nostalgia for nature with a capital N!

The pièce de résistance of the show, however, is the actual tree in a gallery. Leonard’s dead tree had been in her mother’s yard, where it was cloven by lightning. It is another found sculpture in which Leonard has intervened: a dead icon of nature cobbled back together with metal splines, guy wires and braces. It presents an image of nature compromised as much as shored up by the jerry-built array of human interventions. Stairs lead from this tree to a second level of the exhibition that overlooks the tree as if from a terrace.

Zoe Leonard, Untitled, 1989, gelatin silver print, 10 x 8 inches, courtesy of the artist, Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne, and Hauser & Wirth, New York.

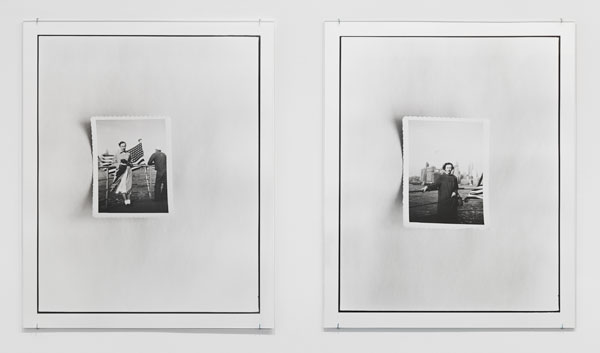

The MOCA installation continues on this terrace, but it is noteworthy that Leonard’s work has simultaneously been on view at two other Los Angeles venues. One is the Los Angeles County Museum of Art’s omnibus exhibition Outliers and American Vanguard Art (on view through March 17). That exhibition contains a display, more elegant than MOCA’s, of Leonard’s only fiction piece, The Fae Richards Photo Archive (1993–96), for which actors were posed. Also overlapping with the MOCA show was a definitive display at Hauser & Wirth Los Angeles of a project not on view at MOCA, “Analogue” (1998–2009). This was a complete set of Leonard’s rigorously documentary series of mom-and-pop storefronts (closed January 20).

In addition to Leonard’s simultaneous presence in these three different venues, two other women photographers of her generation had LA retrospectives that overlapped with hers. “Adrian Piper: Concepts and Intuitions, 1965–2016,” an exhibition of 250 works organized by the Museum of Modern Art, New York, was at the Hammer Museum (October 7, 2018–January 6, 2019) (reviewed in Artillery Jan 2019), and “Sally Mann: A Thousand Crossings” originated at the National Gallery in Washington and then came to the Getty Museum (November 16, 2018–February 10, 2019) (reviewed on p.42)

Zoe Leonard, New York Harbor I, 2016, gelatin silver prints, each: 21 × 17 1/8 inches, courtesy of the artist, Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne, and Hauser & Wirth, New York.

Besides all these exhibitions seen in LA, New York’s Jewish Museum organized a retrospective for pioneer feminist photographer Martha Rosler, on view there through March 3rd. I haven’t tried to count all the mid-career exhibitions of this sort that male photographers have had over the years, but I feel confident claiming that this year has provided women in photography with a time of reckoning.

The range of the sensibilities exemplified by these retrospectives extends from Leonard’s work to Sally Mann’s. Leonard is a hard-nosed New Yorker who travels the world, whereas Mann is a stay-at-home mom whose most noted work takes place in her front yard. While Leonard is terse in her statements, Mann is a garrulous Southerner who evoked William Faulkner in her best-selling autobiography, Hold Still. While Mann’s signature photographs are those of her own children, Leonard’s are not only of far-flung subjects but of other art forms in addition to photography. These two artists could not be more different, exemplifying the universal range of both subjects and points of view that women in photography have embraced.