Mention Blockchain and most people immediately think of Bitcoin. No surprise since Blockchain technology was invented to track transactions of the once-esoteric cryptocurrency. But Blockchain is being touted as a technology that will revolutionize our world, in ways that are unrelated to using Bitcoin or its competitors.

Perhaps one of the most intriguing applications is its potential for changing the way digital and ephemeral art is bought and sold. Take, for example, ascribe.io: a Blockchain-based platform created so that artists and galleries could securely price and quantify digital art for collection. Developments in blockchain technology enabled the creation of limited editions of ephemeral art, pricing them, lending them on consignment, selling them, without worries about attribution, rights management or stray jpegs floating around the internet.

Revolutionary when you think about it because, according to Masha McConaghy, founder of Berlin-based BigchainDB (which ascribe morphed into), the current phase of Blockchain development can be likened to the internet as it existed in 1996: a primitive version. This was the year that Visa, Mastercard, Microsoft, Verisign and other companies first began to establish standards for secure online transactions. It was also an era of ephemeral art-making when artist coalitions and movements such as net.art were using the internet as a medium for visual art (for example, www.jodi.org and www.hell.com), happenings (www.irational.org/cybercafe/xrel.html), and performances (www.mouchette.org), without regard for auctions, dealers or gallery representation.

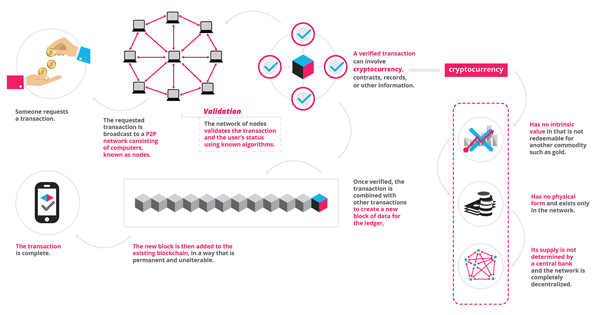

Blockgeeks infographics. Courtesy of blockgeeks.com

Hindsight and 20 years of progress in copyright and fair-use laws now protect artists’ intellectual property online, much of which did not exist in the mid-’90s. One can view Blockchain as an added layer of security for digital and ephemeral art sales, as well as a medium for artistic expression, hence its allure. Blockchain databases are incredibly difficult to hack, simply because the technology was developed and built from a security-first standpoint to withstand attacks. Once a transaction (think: consignment agreement, certificate of authenticity, ephemera, sale) is verified, it is unalterable. A gallery, dealer, or independent artist can protect themselves against fraudulent sales.

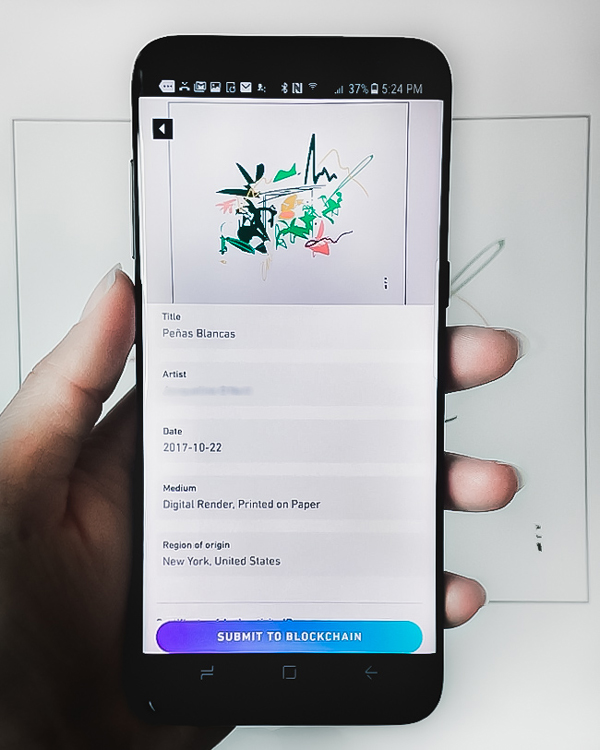

One organization dedicated to doing so is the Blockchain Art Collective, which creates Blockchain-backed certificates of authenticity. Using their app, an artist can register a photo of a physical work of art, affix a seal embedded with an NFC chip, and record all events (sales, transfers, etc.) related to that work of art. Christie’s is also getting in on it—just this past fall, they announced a partnership with Blockchain-powered digital art registry Artory to record and store sales data.

All Public Art Founder and CEO, Graham Goddard, speaking at Blockchain Week London. © All Public Art, Inc. Photo: Frank Angelcyk.

There’s Los Angeles–based All Public Art, which began as an idea to connect tourists with public and street art. Founded in 2015 by fine-artist Graham Goddard, its impetus was to evaluate problems in the larger art market, and then work to create solutions that benefit artists, beginning with app development. As Goddard built his team, he made it a priority to keep up with emerging technologies (VR, AI, Blockchain, etc.), so much so that in 2017, as Blockchain slowly matured, he and his team felt it was time to find ways to integrate it into their platform. APA is now in the process of developing the “APA token” (a Virtual Financial Asset), using the Ethereum database. It will be used as an alternative medium of exchange on their platform alongside the Euro or the U.S. dollar to facilitate crowd-funding and sales for artists and art collectives.

Blockchain Art Asset Registration on Blockchain. Photo: Blockchain Art Collective.

Blockchain technology is a Wild West of opportunity right now, where anyone can do almost anything they set their mind to after getting familiar with the concept—much like the internet in 1996. Niki Williams, US Community Manager for Consensys (a Blockchain venture-production studio), says that artists should be ardently following developments in this technology, yet not for the purposes of mastery—its newness means that standards are just now starting to be agreed upon and built. Williams believes that artists should familiarize themselves with the technology, practice making tokens, and seize the newness of it all by inventing the things they’ve always wanted to, using the lessons learned by the internet boom. For instance, what does visual art look like when you use a Blockchain database as your medium? What does a happening look like? What does a performance look like? What does text look like?

Established art-world businesses are notorious for being behind the curve on emerging technologies, but that’s certainly not the case when it comes to Blockchain. New art businesses are forming to address longstanding concerns around security and attribution. Artists now have a real chance at being equal partners with galleries and dealers in the promotion of their careers.