The news of BLUM’s abrupt closure after 30 years in Los Angeles reframed the landmark gallery’s final exhibition, Wilhelm Sasnal’s “AAAsphalt,” into an inadvertent elegy for contemporary art in Los Angeles. Entering the massive complex on an early July afternoon, I played business-as-usual with the gallery’s skeleton crew, but BLUM’s routine silence was changed—vacuous, tense, and terminal—the swan song of a soon-to-be bygone way of gallery life. This feeling doubled as I passed from foyer to gallery, where Sasnal’s peopleless Los Angeles was scattered across 20 paintings and a lone sculpture.

Based on his brief stay in the city, the Polish artist anchors his recent body of work in everyday monuments—cactus trees, traffic crossings, birds in flight. Marred by environmental collapse and social atomization, Sasnal’s LA isn’t exactly dystopian, but it’s on its way. Drifting from landscape to object to architecture, between projection and self-reflection, the show resembles the artist’s psychic space more than any greater narrative or thematic, making my task of distilling its core as elusive as capturing LA itself. The air of distraction in “AAAsphalt” also embodies the crisis of creating a lasting image in an oversaturated visual landscape, compounding the unintelligibility of Los Angeles and the inadequacies of painting as a means to represent it.

While in LA, Sasnal elected to travel by bike, lending him an outsider’s acuity towards facts of life to which the locals have gone blind, both as a cyclist in a car-dominated city and a foreigner in the States. Like most LA stories, this show is organized around the street. The concept most overtly bolsters experimentations with matte black paint, as seen in the show’s anomalous text paintings. Titled Asphalt (2025) and All-American (2025), these works toy with the notion of black as invisibility on a representative surface, inverting the tenets of Chiaroscuro lighting. The works’ titles barely surface beyond the void filling the canvas, legible only due to light clumping along the edges like gathering dust. Similar to the overlooked and underfoot asphalt that defines Los Angeles, Sasnal’s black is foundational, but also invisible.

Wilhelm Sasnal, Wiltern, 2025. Photo: Evan Walsh. Courtesy of BLUM.

Opacity is clearly on Sasnal’s mind, located within neglected subjects, but also those willfully obscured. In Wiltern (2025), Sansal renders LA’s natural environment in silhouette, but the silhouettes are created not by cast light but by vandalism so dark that it completely obscures the subject. Smothered in heavy tar-like paint, the effect is an ecology in absentia, a natural life that’s been trampled and forgotten. In another vein, twin diptychs hanging on the introductory wall, Palmdale 1 & 2 (both 2025), depict abstracted forms derived from photographs of fighter jets taken at an Air Force production plant. Rendered in hypnotic relief, Sasnal folds wingtips and rudders onto themselves until encoded in an unrecognizable composition. Shrouded within aesthetic bureaucracy, formal complexity echoes the way a system’s inscrutability deflects closer inspection—hiding the minotaur behind the labyrinth, if you will.

Owing to his process of painting from photography, Sasnal transacts in disclosure and withholding. In transit between mediums, a process of elimination omits certain visual details and embellishes new flourishes at will, leading to an application of paint working in extremes. Much like Luc Tuymans, Sasnal is drawn to hyperbolically high contrasts, hiding features between glare and shadow. While this infuses authorship into the work, as certain biases are inevitable in the act of translation, it also positions painting’s capacity for representation as inferior compared to photography’s faux-objectivity, to Sasnal’s apparent frustration.

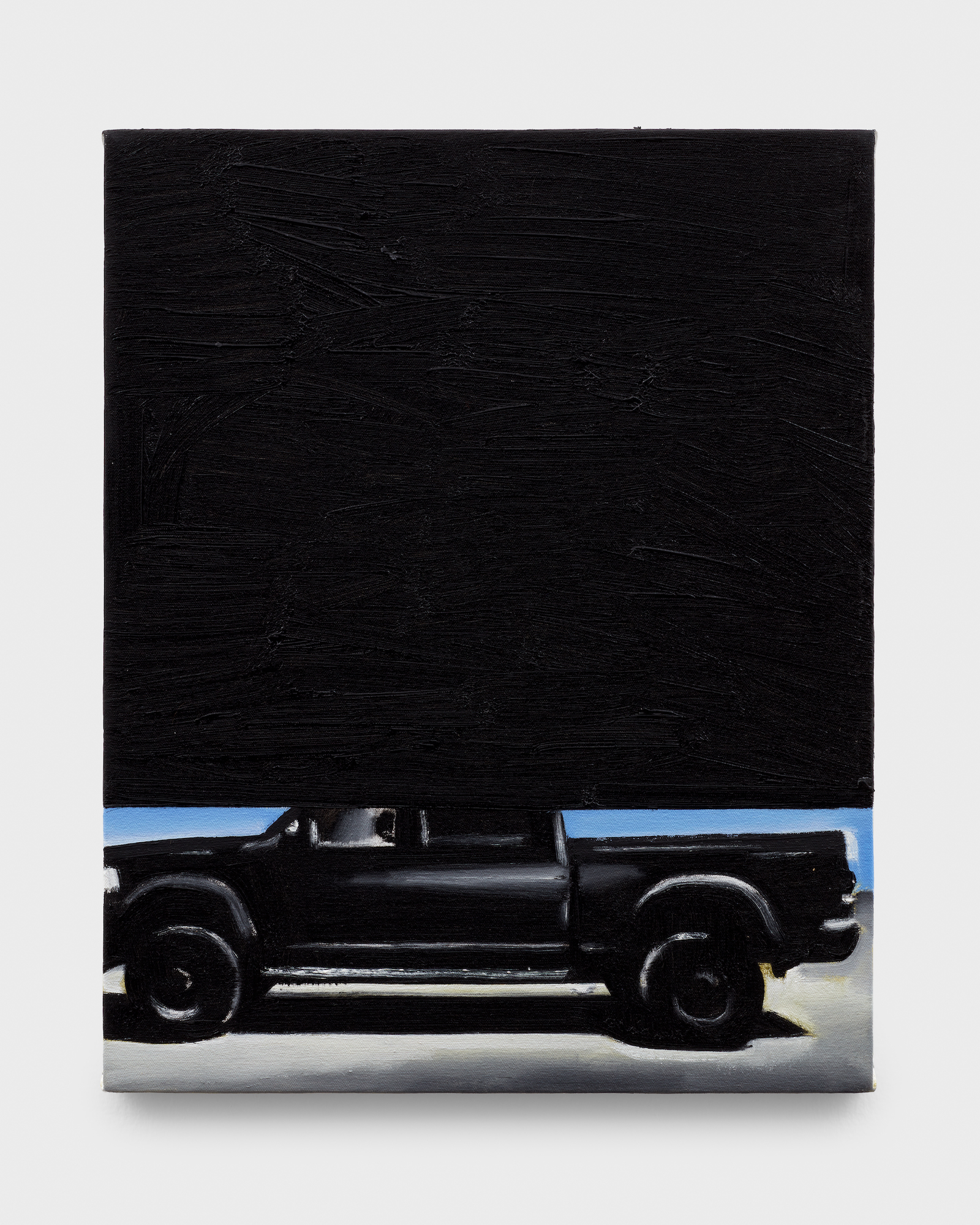

In Untitled (Silver Lake) and Untitled (Pick-up) (both 2025), parallel compositions depict monochromes above painted images: solid black over a pick-up truck, and red over a Roman ionic capital. Whereas the monochromes are flat and inscrutable, the lower sections awkwardly approximate their photographic references, sketching out whichever details Sasnal liked best. There’s friction between the zeal of the painterly effort and the medium’s communicative capacities compared to that of the photographic referent, a tension that encapsulates Sasnal’s pessimism about painting’s inadequacies in the contemporary era. If factual documentation is the aim, then painting just cannot compare to the lucidity of a photograph, much less when depicting a city as elusive as Los Angeles.

Wilhelm Sasnal, Untitled (Silver Lake), 2025. Photo: Evan Walsh. Courtesy of BLUM.

What’s more, when placed within the scattered field of view of “AAAsphalt”, what value can painting’s bid for monumentality be said to offer our contemporary moment’s fleeting attention spans? One answer might be in art’s ability to reject all notions of objectivity, championing stillness found in the subjective. However, to unwind the complexities of that perspective would require pulling your eyes away from the myriad sensations competing for attention—a mediation that is increasingly too much to ask of a contemporary viewer.

And in the art world, as above, so below. Tim Blum justified his decision by citing a new art market that he didn’t recognize: collectors more interested in flipping than owning, partying than buying (much less, appreciating). Dopamine rules the market more than any pure investment in art, emotional, or financial. So, paintings and galleries are in a similar bind, but it is not a crisis of obsolescence, as Sasnal fears, but rather of relevancy—of application to the contemporary context. If they hope to survive, both painting and the greater art market will need to evolve.