If one were to Google Canadian artist Eli Langer, most of the results would reference a convoluted legal case against his first show (held at Toronto’s Mercer Union Gallery in 1993) that proclaimed the subject matter not simply to be pornography but child pornography—Canada’s version of the late-’80s Jesse Helms morality and censorship cluster-fuck. The paintings and sketches, only glimpses of which are available online, are sometimes emetic and sometimes hilarious: terrifying, neo-Sadean humor. All of the scenes from that period, with the exception of the sketches, are in deep oil shades of crimson and charcoal, dark and sometimes nearly unreadable. Children toy with themselves or each other curiously; a lecher implores an overwhelmingly bored child: a brief glimpse into a stalled moment before the event branches out into pathology. To this day, while Langer won the case both in court and in the press, he is frequently stopped crossing the border because, as it turns out, those charges don’t ever really go away.

Eli Langer, #48

I first met Langer in Los Angeles in 2013 (at that point, his home for over a decade). We spent an entire night shooting a BB gun at objects in his studio while our mutual friend Sylvie slept on the massive bed in the room’s center, surrounded by a canopy of thin sheets like a nocturnal veil. Books on every period of art from his self-education and days of teaching at UCLA lined the multitude of jerry-rigged shelves; rolled canvases containing color fields and measured studies in abstraction from past exhibitions along with boxes of drawings filled every available corner of the room.

Eli Langer, “0, 2016-17

Prior to the shooting gallery, Sylvie and I chased Langer through the city, dodging him in alleyways and yellow lights on Hollywood Boulevard, trailing his retired police vehicle in Sylvie’s partially wrecked Toyota. A week later, when I ran into him at a gallery, he claimed not to recognize me. The police car was totaled by a friend after Langer left Los Angeles in 2015 to care for his dying father.

Eli Langer, #18, 2016-17

By the summer following our initial encounter, Langer and I had become close confidantes, taking long walks into the side gardens of Griffith Park and talking about metaphysics and mysticism. He knew every homeless person in the neighborhood by name, and hugged and conversed with most of them; each transaction with the local shopkeepers was marked by a combination of confidence, self-consciousness, suspicion and absurdity that I increasingly mimicked. Our telephone conversations progressively resembled glossolalia, continuing beyond his departure from the city to the present day.

Eli Langer, #29, 2016-17

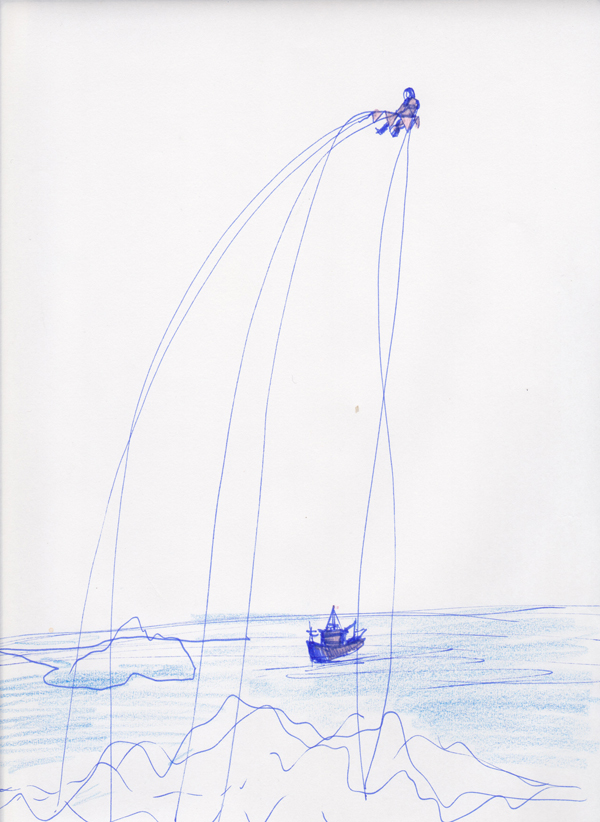

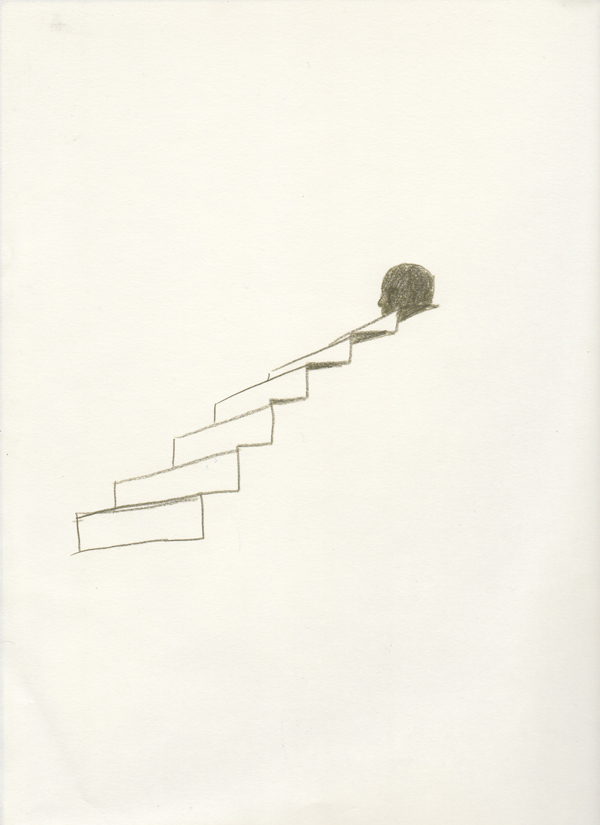

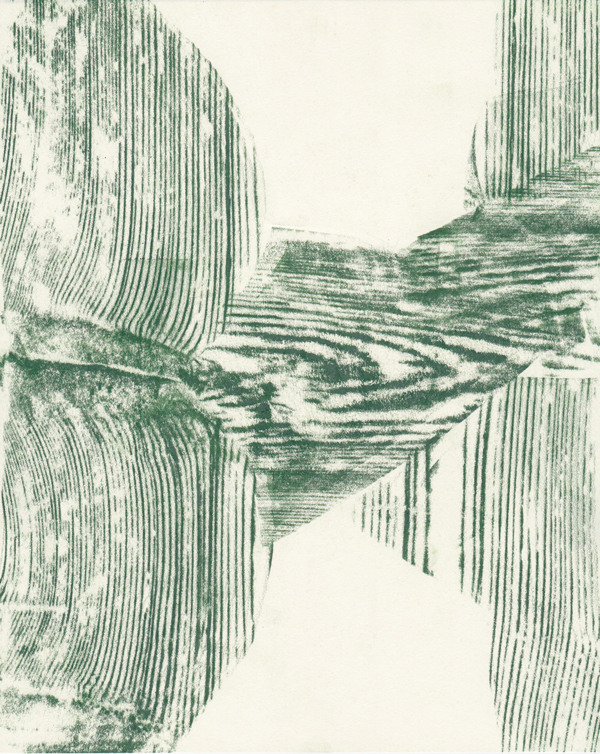

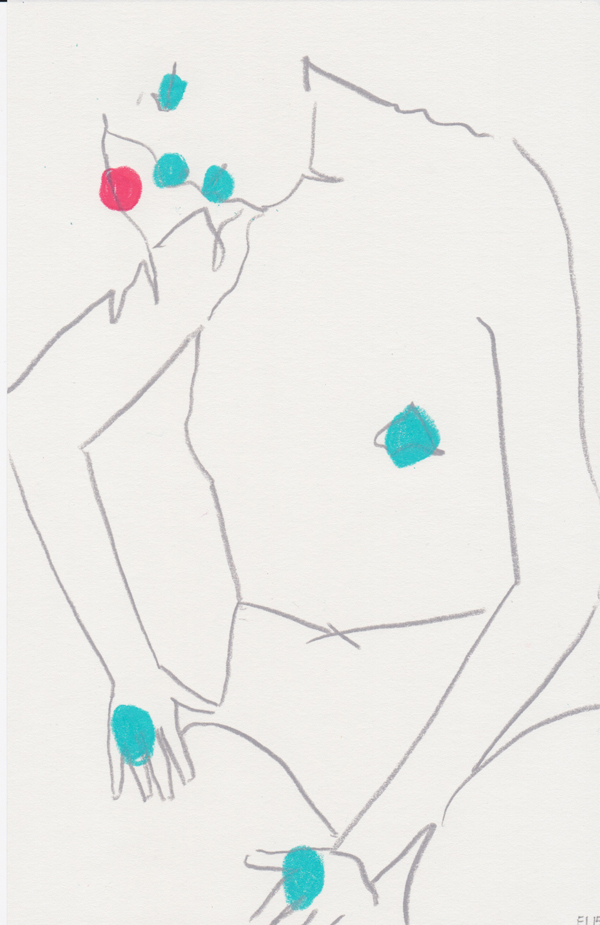

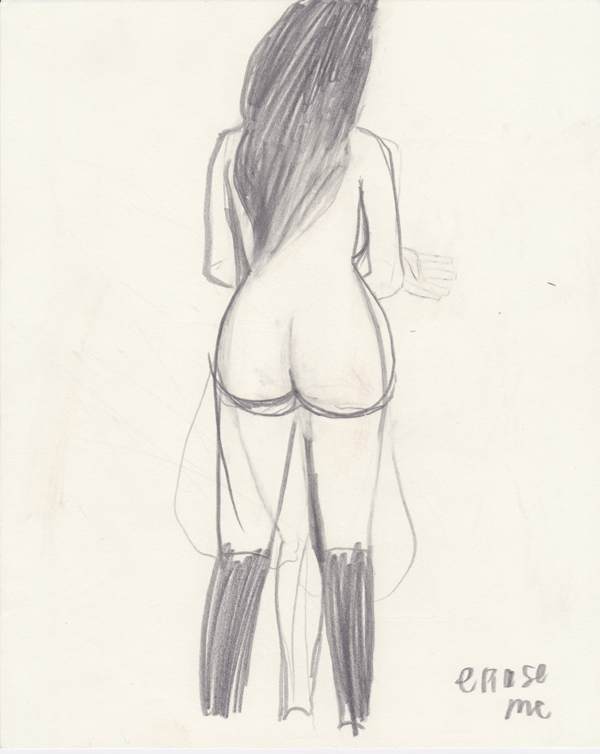

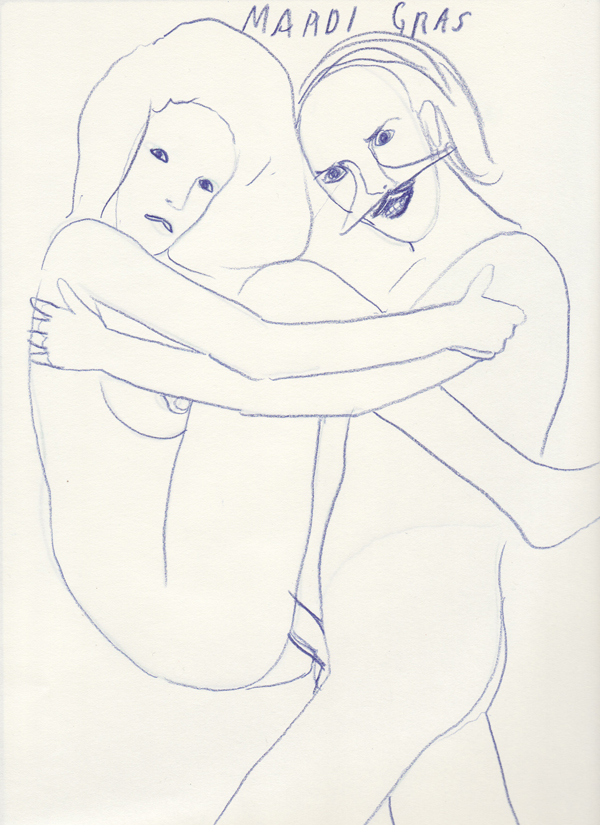

From his current semi-seclusion—and after haranguing him for weeks—Langer emails me 50 or so sketches out of the thousands upon thousands he’s created and managed to retain through moves both domestic and international. The fantastical illusions stand alone on a white page or accompanied by lettered free association, sometimes mirages that shake around their surface in tremulous lines. Others are wood rubbings—frottage—that take the form of sex acts or floral arrangements like in 9 and 18 (all of the titles just numbers), the textured ochre strokes defining one body or part moving into another or a healthy leaf, the knots forming openings and botanical stigmata. Each segment is at once lucid but vague, magnified to the point of obscurity.

Eli Langer, #51, 2016-17

In 51, a woman stands with her ample rear in the center, her long hair falling along her back, and I’m reminded of bathing in the same room as Langer, talking from opposite ends of his studio in the Mediterranean heat. There are erasure marks: at one point her legs were together, almost crossed, and her lower body was clothed. A hand offered as a greeting or a tool to count, possibly to make a point, is voided. It has an epigraph: “Erase me.” She appears nervous now, her hands together in front, maybe wringing—watched. The same woman appears in 39, confident, clothed in a translucent slip. There is an outline of her moments before, flinging her skirt around in celebration.

Eli Langer, #5, 2016-17

For a month in 2016 Langer christened himself Felix Lang, then decided against it because, really, naturalia non sunt turpia: “what is natural is not dirty.”

Image courtesy Cayal Unger