It has not escaped me that the order of these posts keeps keeps getting juggled as one thing or another interrupts the chronological flow. (Or perhaps it’s the ‘controversial’ flow—as controversy is what frequently drives this conversation forward.) But occasionally we get a break; and sometimes that break provides us with another, longer, cooler (though not less troubling) perspective. So it was the other evening when I took a walk (I almost want to say hike) through Nature and the American Vision: The Hudson River School.

I was lucky enough to have Dr. Linda Ferber, who curated the show from the holdings of the New York Historical Society, along for a brief segment of this tour. She probably knows the Historical Society’s collection better than anyone in New York or anywhere else in America. (And why not? She was the museum’s Director for eight years.) She seemed to know everything about each of the paintings, the artists who created them, the details of their execution, the collectors who commissioned or acquired them, and every bit of history or legend remotely connected to them, from their place in in the City or State of New York, their connection to the Hudson River School, and for that matter, the art (and world) far outside New York, to Europe and beyond.

I was lucky enough to have Dr. Linda Ferber, who curated the show from the holdings of the New York Historical Society, along for a brief segment of this tour. She probably knows the Historical Society’s collection better than anyone in New York or anywhere else in America. (And why not? She was the museum’s Director for eight years.) She seemed to know everything about each of the paintings, the artists who created them, the details of their execution, the collectors who commissioned or acquired them, and every bit of history or legend remotely connected to them, from their place in in the City or State of New York, their connection to the Hudson River School, and for that matter, the art (and world) far outside New York, to Europe and beyond.

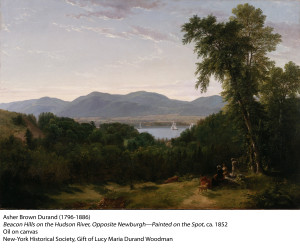

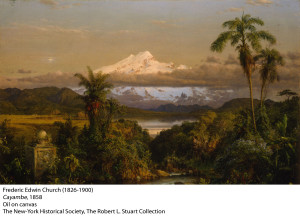

She might have held us rapt with her disquisitions on any of the artists or their subjects—Thomas Cole, Asher Durand, Albert Bierstadt, Frederic Edwin Church, et al.—but I was especially drawn to some casual remarks she made to another writer at the preview connecting Frederick Law Olmsted with the pictorial lineage of the Hudson River School. I suppose this might be attributed to a state of nostalgia-intoxication. This was all about my native turf, after all; and with the weather here already getting warmer and beginning to dry out, I was missing those familiar Central Park vistas (and New York streets). But the vision and plan Olmsted and Calvert Vaux carved out for Central Park relate not simply to the pictorial vision of the Hudson River School, but a vision of an urban society borne out of the agrarian democracy for which these arcadian visions served as both ideal and emblem. As the city has realized the imperial ambitions of the Empire State over the last couple of centuries, Central Park may just remain its anti-imperial soul.

Olmsted and Vaux were themselves mentored by (ironically named) Andrew Jackson Downing, a landscape architect and nurseryman, who was responsible to some extent for popularizing an English picturesque style of garden design for estates up and down the Hudson River Valley. His magazine, The Horticulturalist, became to some extent the ‘house organ’ for the Hudson River School. (William Cullen Bryant was for a time its editor.)

Olmsted and Vaux were themselves mentored by (ironically named) Andrew Jackson Downing, a landscape architect and nurseryman, who was responsible to some extent for popularizing an English picturesque style of garden design for estates up and down the Hudson River Valley. His magazine, The Horticulturalist, became to some extent the ‘house organ’ for the Hudson River School. (William Cullen Bryant was for a time its editor.)

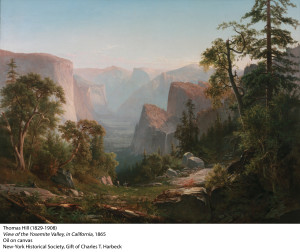

Somewhere between the two, a landscape cliché was born that spawned more cheap imitations than empire-builders from Ray Kroc to Thomas Kinkade could have possibly imagined. I ran into another writer somewhere between the Resnick Pavilion and the Stark Bar, who complained about the derivative sameness of many of the landscapes (also walls shaded too similarly to those of the Samurai exhibition space the next gallery over). He had a point. The similarity in composition and perspective of strikingly dissimilar landscapes (e.g., West Point and, say, Yosemite Valley) elicits a certain impatience. It’s as if Hokusai had actually sketched views of 36 different places and just made them all look like Mount Fuji.

Somewhere between the two, a landscape cliché was born that spawned more cheap imitations than empire-builders from Ray Kroc to Thomas Kinkade could have possibly imagined. I ran into another writer somewhere between the Resnick Pavilion and the Stark Bar, who complained about the derivative sameness of many of the landscapes (also walls shaded too similarly to those of the Samurai exhibition space the next gallery over). He had a point. The similarity in composition and perspective of strikingly dissimilar landscapes (e.g., West Point and, say, Yosemite Valley) elicits a certain impatience. It’s as if Hokusai had actually sketched views of 36 different places and just made them all look like Mount Fuji.

And there is a derivative, formulaic aspect to much of this painting, not unlike the picturesque traditions inherited by landscape architects and garden designers from Capability Brown and later English architects and designers (though it would be absurd to categorize Brown’s naturalism as simply ‘picturesque’). In fact, the ‘formula’ goes back still further to England, France and Italy—to Constable and the Barbizon School; and still more distantly, to Poussin, even Piero di Cosimo. Like so many of these proto-Romantic paintings, the mood and atmospheric quality are pitched somewhere between the picturesque and the sublime. The key difference is exemplified in some of the less typical examples here (e.g., Louisa Davis Minot’s Niagara Falls). In other words, these were in fact wilderness landscapes like no others, as sublime and forbidding as any of Europe’s alpine splendors, as exotic as the tropical jungles still being explored for the first time.

And there is a derivative, formulaic aspect to much of this painting, not unlike the picturesque traditions inherited by landscape architects and garden designers from Capability Brown and later English architects and designers (though it would be absurd to categorize Brown’s naturalism as simply ‘picturesque’). In fact, the ‘formula’ goes back still further to England, France and Italy—to Constable and the Barbizon School; and still more distantly, to Poussin, even Piero di Cosimo. Like so many of these proto-Romantic paintings, the mood and atmospheric quality are pitched somewhere between the picturesque and the sublime. The key difference is exemplified in some of the less typical examples here (e.g., Louisa Davis Minot’s Niagara Falls). In other words, these were in fact wilderness landscapes like no others, as sublime and forbidding as any of Europe’s alpine splendors, as exotic as the tropical jungles still being explored for the first time.

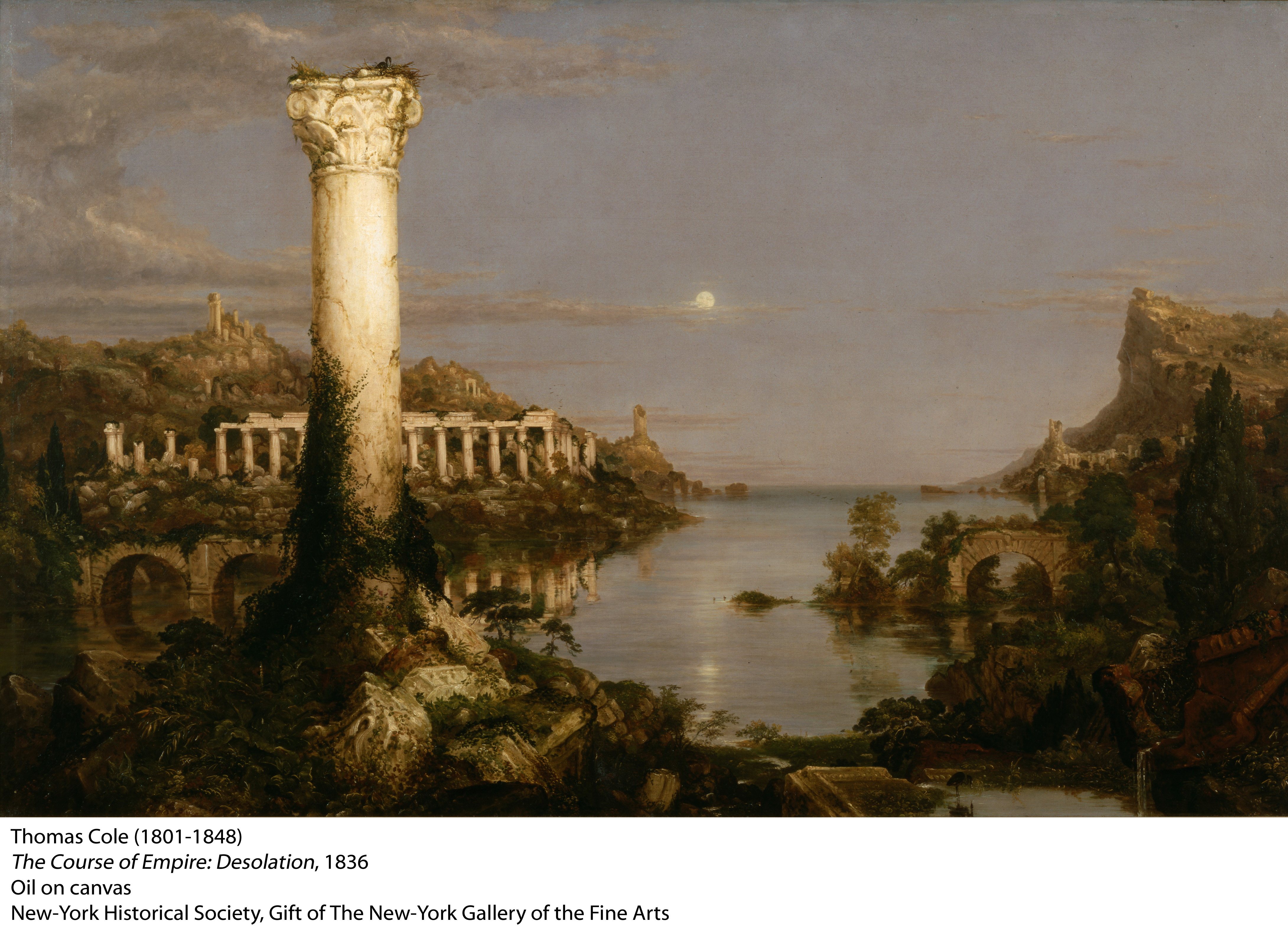

American corruption would inevitably overtake the ‘American Vision.’ As this style and its practitioners were moving across the rapidly expanding, settling, civilizing, and finally industrializing country—fulfilling the Jacksonian promise of Manifest Destiny—the pastoral, Arcadian ideal the style evoked was increasingly compromised. In Albert Bierstadt’s Donner Lake from the Summit, we see the railroad crossing the hills clearly in the (partially cleared) landscape—a pastoral already transformed for commerce and industry. In contemporary terms, such a landscape is scenic enough to satisfy the requirements of tourism, but we can be sure that subsequent developments will have left deeper, toxic scars. Who would have guessed in 1836 that Thomas Cole’s Desolation (part of his Course of Empire sequence of paintings) would ultimately seem optimistic?