Andy Warhol is having another “Moment.” He continues to remain a huge part of the social and artistic zeitgeist decades after his death. His Warhol Diaries are currently dramatized in a multi-part documentary on Netflix (narrated by a spooky robotic-voice AI “Andy”) and several Warhol theatrical dramas will be on the boards in coming years.

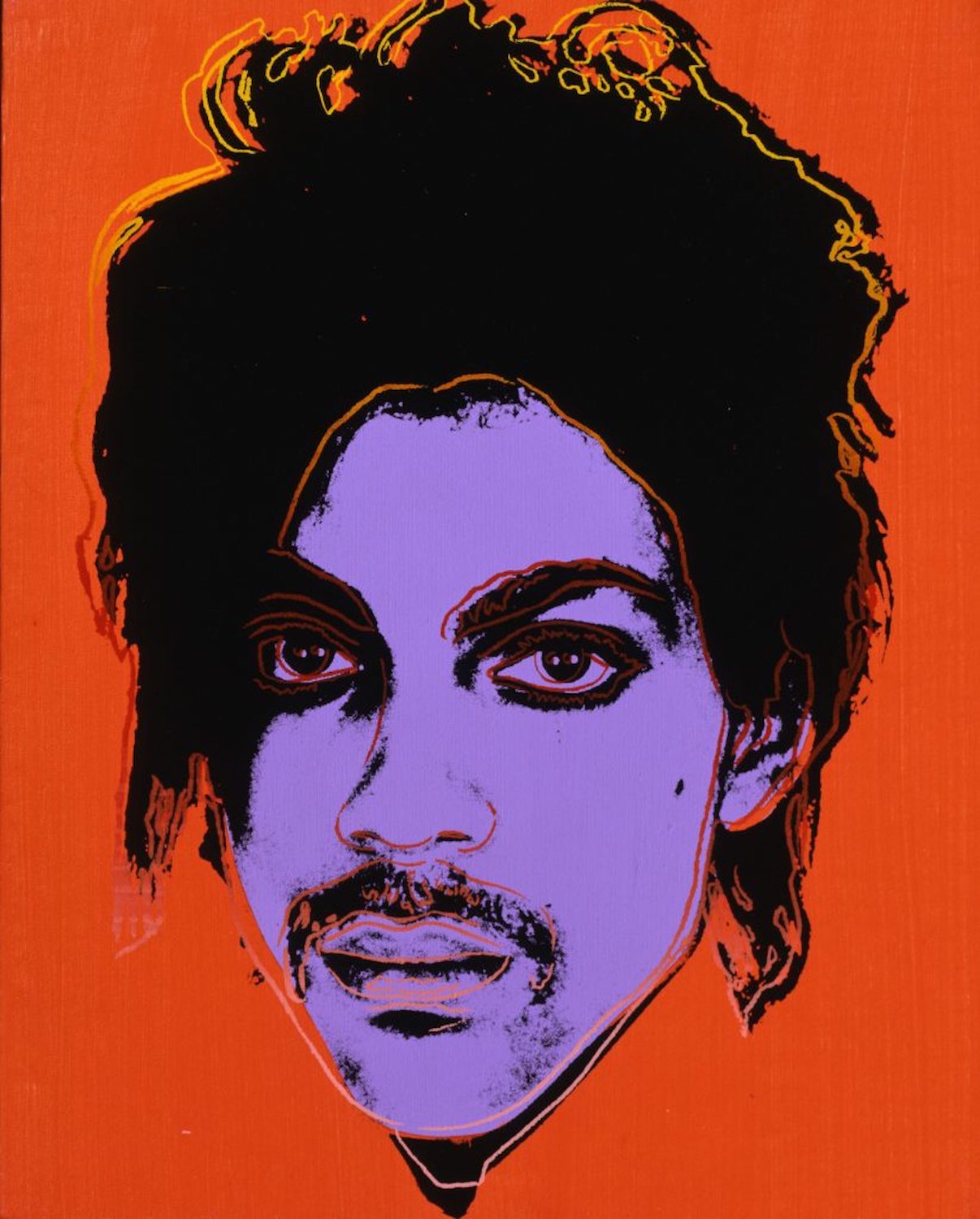

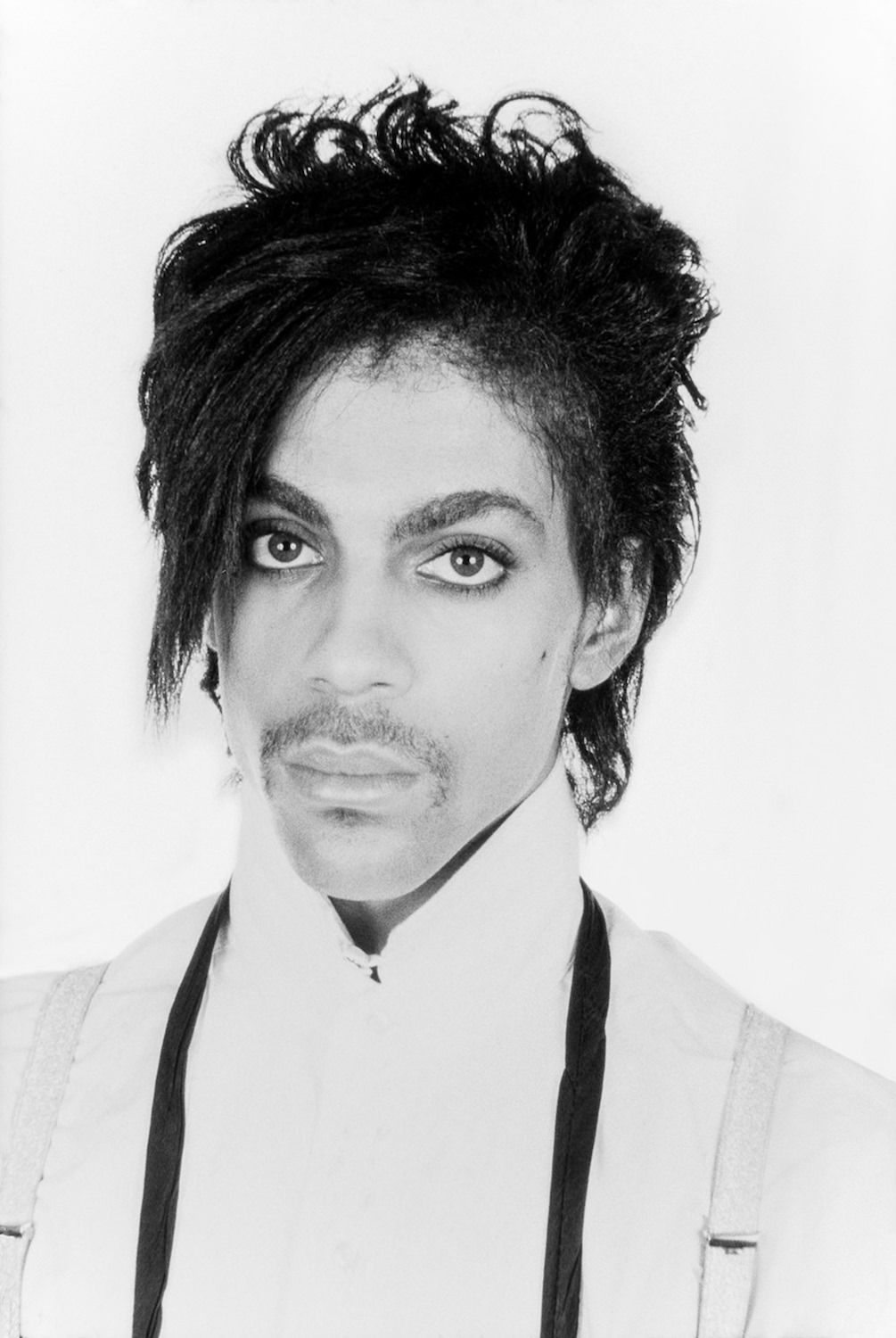

Less foreseen, one of Warhol enduring legacies may be on copyright law. The U.S. Supreme Court announced in March that it was taking up a case that has been wending its way through the federal courts for years. This copyright infringement litigation concerns the claim of art photographer Lynn Goldsmith that Warhol infringed her 1981 photo portrait of the super-star recording artist known as Prince. The original photo appeared in black and white while Warhol’s version was cropped and colorized in purple for a 1984 article, “Purple Fame” in Vanity Fair in conjunction with Prince’s release of his Purple Rain album (Warhol subsequently made a series of 15 alterations of the photo).

The Warhol Foundation successfully defended against Goldsmith’s claim in federal district court, but the decision was reversed by the Second Circuit Court of Appeals (N.Y.) which is known for its copyright expertise. The March 2021 Second Circuit decision in Goldsmith’s favor was a virtual treatise on the fair use defense to infringement, leaving the matter to the Supreme Court for what could be a landmark decision in its next term.

The assertion of the defense of fair use by artists such as Jeff Koons and Richard Prince, practitioners of the art of appropriation, has been the subject of several Art Brief columns over the years. The issue usually comes down to whether the alleged infringing artist has “transformed” the original work sufficiently. The complex analysis for the courts ultimately requires a subjective decision by judges, all too often turning them into art critics—a role they are woefully unsuited for. As Justice Potter Stewart famously said about pornography, “I know it when I see it.” That standard may work for obscenity cases, but it fails when it comes to judicial artistic critique.

The copyright act sets out four factors courts must examine in fair use cases: (1) the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature; (2) the nature of the copyrighted work; (3) the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole; and (4) the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.

Lynn Goldsmith’s photograph of Prince, 1981

The Second Circuit court found that the first factor should explore whether the secondary work is “transformative,” as well as being commercial. In examining this first factor, the court held that the lower court made an “error” in finding that the Warhol works are transformative because they “can reasonably be perceived to have transformed Prince from a vulnerable, uncomfortable person to an iconic, larger-than-life figure.”

“Though it may well have been Goldsmith’s subjective intent to portray Prince as a ‘vulnerable human being’ and Warhol’s to strip Prince of that humanity and instead display him as a popular icon, whether a work is transformative cannot turn merely on the stated or perceived intent of the artist or the meaning or impression that a critic—or for that matter, a judge—draws from the work. Were it otherwise, the law may well recognize any alteration as transformative.”

“Instead, the judge must examine whether the secondary work’s use of its source material is in service of a ‘fundamentally different and new’ artistic purpose and character, such that the secondary work stands apart from the ‘raw material’ used to create it …The secondary work’s transformative purpose and character must, at a bare minimum, comprise something more than the imposition of another artist’s style on the primary work such that the secondary work remains both recognizably deriving from, and retaining the essential elements of, its source material.” Therefore, the court concluded that the Warhol Prince series is not transformative. The court also found that commercial use was present since the Warhol work was used to illustrate the Vanity Fair article.

The third factor was also examined—the courts must “consider not only the quantity of the materials used but also their quality and importance.” The court held that the “Warhol borrows significantly from the Goldsmith photo both quantitatively and qualitatively.”

Finally, the fourth factor—harm to Goldsmith’s derivative market was “substantial,” something the lower court “overlooked.”

With the loss of the Supreme Court’s two copyright experts, Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Stephen Breyer, I would not be surprised if the Supreme Court affirms the Second Circuit’s decision against the Warhol Foundation, in deference to that court’s history of important copyright rulings.