I’ve always thought the human preoccupation with borders and perimeters had more to do with its relationship with animal wildlife (not that humans have ever exactly been ‘tame’). I realize I’m speaking a bit off the top of my head – I’ve never done any serious research into this. But my superficial take-away from what I have learned about natural history over the years is that we’ve been a wandering species pretty much since the earliest hunters and gatherers. We’ve also been a species of inventors (on the plus side), tale-spinners, and mythologizers (and not incidentally, self-mythologizers). I tend to think the earliest mythological and medieval bestiaries had their origins in human wanderings past their immediate surrounding environments and tribal domains and the tall tales such wanderers spun when they returned to the places their tribes and families were tenuously homesteading, with their descriptions of wildlife embellished to emphasize the mysteries and dangers they encountered. (To enhance their standing in the ‘tribes’? To make themselves more attractive as mating material? When their potential mates were probably just thinking, ‘you jerk’?)

In the meantime, our fellow creatures were also on the move, though somewhat less ambitiously – usually in search of a good meal. Unlike our competitive and haphazardly creative species, they tended to stick to their own metropolis of the wild. Also unlike our self-mythologizing species, those quests actually entailed serious hazards, and occasionally mortal conflict with competitive species. Walton Ford’s great subject has always been, not simply a reconceived bestiary along the lines of the great naturalist and natural history painters and illustrators, but the fraught and tragic intersections and confrontations between these human mythologies and the wildlife humans have variously feared, revered, hunted, admired, exploited, tortured and killed to the point of extinction.

Mythology is rife with rationalizations for human misbehavior, and human civilizations have not shied away from exploiting such ideas and motives to rationalize their own extensions and expansion into unprotected wilderness and for that matter colonial exploitation (by way mythology’s successors – Western religions). Ford makes one such latter-day mythology – the Spanish legend of Calafia – a motif actually taken from a 16th century novel by Garci Rodríguez de Montalvo which inspired the Spanish conquistadors to name this part of the American southwest ‘California’ – the focus of his show at Gagosian. In the original novel, the island of Esplandian (Calafia is its queen) is inhabited by flying griffons. In Ford’s Calafia, the griffin is California-nized into a half-California condor, half-native mountain lion beast, encountering a California (‘island’ only in political terms) transformed by human encroachments. In Isla de California, we see a magnificent specimen with its stealth-span articulated wings and lavender breast swooping in to land on one such emblem of progress – the utility pole – looming in the foreground in the hills over Malibu. Some distance away another such creature can be seen making explosive contact with a transformer. The year 1938 appears after the title – obviously bearing no relationship to the inscription from the Rodríguez de Montalvo novel, but not insignificant. We can trace California’s evolution through such dates – from its original Spanish ranchos to agricultural, small local industry and land development companies, and finally to what it is today.

Mythology is rife with rationalizations for human misbehavior, and human civilizations have not shied away from exploiting such ideas and motives to rationalize their own extensions and expansion into unprotected wilderness and for that matter colonial exploitation (by way mythology’s successors – Western religions). Ford makes one such latter-day mythology – the Spanish legend of Calafia – a motif actually taken from a 16th century novel by Garci Rodríguez de Montalvo which inspired the Spanish conquistadors to name this part of the American southwest ‘California’ – the focus of his show at Gagosian. In the original novel, the island of Esplandian (Calafia is its queen) is inhabited by flying griffons. In Ford’s Calafia, the griffin is California-nized into a half-California condor, half-native mountain lion beast, encountering a California (‘island’ only in political terms) transformed by human encroachments. In Isla de California, we see a magnificent specimen with its stealth-span articulated wings and lavender breast swooping in to land on one such emblem of progress – the utility pole – looming in the foreground in the hills over Malibu. Some distance away another such creature can be seen making explosive contact with a transformer. The year 1938 appears after the title – obviously bearing no relationship to the inscription from the Rodríguez de Montalvo novel, but not insignificant. We can trace California’s evolution through such dates – from its original Spanish ranchos to agricultural, small local industry and land development companies, and finally to what it is today.

Yet Ford’s scheme here is clearly intended to match ‘Manifest Destiny’ expansionism with a temporally expansive scheme of its own. This is an ‘Isla’ that moves forward and back through time. In another painting, the Grifo de California sprawls against the cliffs in repose, its furry black mantle and white under-plumage splendidly articulated. The date inscribed is 1533, which may have marked the first Spanish expeditions into California – or at least Baja California (Cortez entered Mexico in 1519, and by 1532, Pizarro had taken the Incan empire of Peru.); but serious Spanish colonization of California would not begin until the 18th century.

Ford gives us a glimpse of that period (1749?) in La Madre – the mother referenced in the title being a grizzly bear, ensnared (though not fatally) by some part of a trap seen just inches from her claws. Oso Madre appears suspended here somewhere between fight and flight; and just to her left, in a meadow far below the cliff’s edge, we glimpse what has frozen her in terror – not for herself, but for her cubs. It’s hard not to almost instantly leap to the assumption that the bears in the meadow being chased by a trio of horsemen – not far from a structure that looks like a Spanish mission – are her own, at least in spirit. The pathos we read in her eyes may simply be more anthropomorphizing on the viewer’s part – this, too, being part of Ford’s subject here. But this contemporary anthropomorphizing has more to do with time. Where our hypothetical Madre’s thoughts are likely only on the immediate whereabouts of her cubs, the contemporary viewer has a privileged view of what will unfold in the future. Ranchos and missions will continue to be claimed, cleared, variously cultivated and plundered; and small and large native species alike (humans included) exploited to the verge of extinction.

Then, too, this is another warm-blooded mammal not so far removed from the super-predator species – and who has not seen fear in a cornered or panicking animal’s eyes?

Unlike our colonial predecessors, Ford gives due respect to the mythical Esplandian queen. In La Brea, a triptych roughly 30 feet long (and 5 feet tall – the three panels were each 60.5 x 119.5 inches) that took up an entire wall of Gagosian’s Beverly Hills gallery, the sun rises somewhere to the east of a prominence (between Inglewood and Baldwin Hills?) overlooking what might be the post-Rancho/pre-20th century La Brea Boulevard itself – we can see the most prominent thoroughfares that will mark the urban grid. Climbing over the hills, though, we see some very large animals, including a few species that could only have crossed into North America in Rodriguez de Montalvo’s imagination – further complicating the ‘when’ of this scheme. The second panel shifts the focus further into the foreground, and a kind of waking nightmare. Familiar silhouettes give way to what we can see are intended as prehistoric specimens come back to life, shlepping up hillsides fresh from the tarry lakes that gave the rancho and later the boulevard its name. Vengeance is taken in the last panel on a hillside we now recognize as the Hollywood Hills (John Lautner’s Chemosphere house – owned by Ford’s patron, Benedikt Taschen looms in the background) where two tar-slicked saber-tooth tigers pounce upon a comparatively defenseless local mountain lion – not all that distant from an actuality where it’s just as likely to die from blunt force trauma (as in automobile collision) or rat poison.

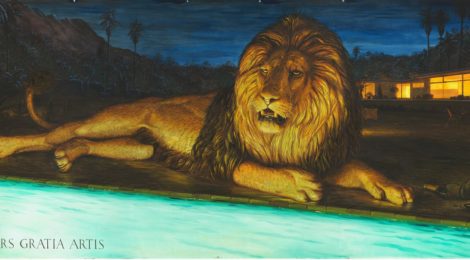

No nostalgia is possible here (as if we needed to be reminded in Hollywood where no house goes unburned!). But Ford updates the disillusionment with a glassy-eyed Leo the Lion lounging poolside at a more generic contemporary canyon abode in Ars Gratia Artis (2017) – which pre-GenX-ers might remember as the motto of M-G-M. Nothing but mergers and merchandising on this horizon, though we can hope the residuals keep coming in. The dream factory is gone – and so are the dreams. Yet some of us (even in Hollywood) go right on dreaming them.

No nostalgia is possible here (as if we needed to be reminded in Hollywood where no house goes unburned!). But Ford updates the disillusionment with a glassy-eyed Leo the Lion lounging poolside at a more generic contemporary canyon abode in Ars Gratia Artis (2017) – which pre-GenX-ers might remember as the motto of M-G-M. Nothing but mergers and merchandising on this horizon, though we can hope the residuals keep coming in. The dream factory is gone – and so are the dreams. Yet some of us (even in Hollywood) go right on dreaming them.

Of course the great thing about Leo’s Hollywood was that it never bought its own press. Today culture and technology seem to push in the opposite direction – seemingly manufacturing and consuming it in a chain reaction spin cycle. (That is, when it’s not trying to break it or shut it down.) Ford’s is an alternate version, an alternate dimension, removed from this relentless fakery. Lions and griffons and bears (‘oh my!’) are really at the periphery of this human-centered diorama, where the past can and will return to haunt us – much as the melting icecaps and plastic-filled oceans will eventually melt and suffocate us.