Given his outsize influence on Conceptual art, it’s surprising that Piero Manzoni is just now getting his first official biography. By the time he died in 1963 at the early age of 29 from a heart attack, he had pioneered a genre of painting without color, canned his breath and excrement as art works, issued numerous manifestos, signed living people as art works, and had managed (in a pre-internet world) to cement his international reputation. There have been numerous large-format books on his art in the last two decades—some including scholarly essays—but this is the first chronological biography.

Book cover.

Manzoni was born to a count (a title that he inherited) whose wife came from a prominent family. When his father died during Manzoni’s 15th year, his mother was left with sufficient resources to maintain a well-heeled existence. He could always count on her for financial assistance, and the family home was his primary residence for the rest of his life. He did not take up art right away. To somebody of his social class, painting was an acceptable hobby. It was in that spirit that he first took up a paintbrush in his spare time, while he set out to study law. He eventually dropped out of law school and became a self-taught painter. He worked with a local group staging shows and issuing proclamations. Early on he realized the importance of networking with art critics to achieve his ambitions. He co-founded a gallery and magazine in 1959, which brought him into contact with other artist groups. He is considered a precursor to Conceptual art, performance art, body art, and was a key influence on Arte Povera.

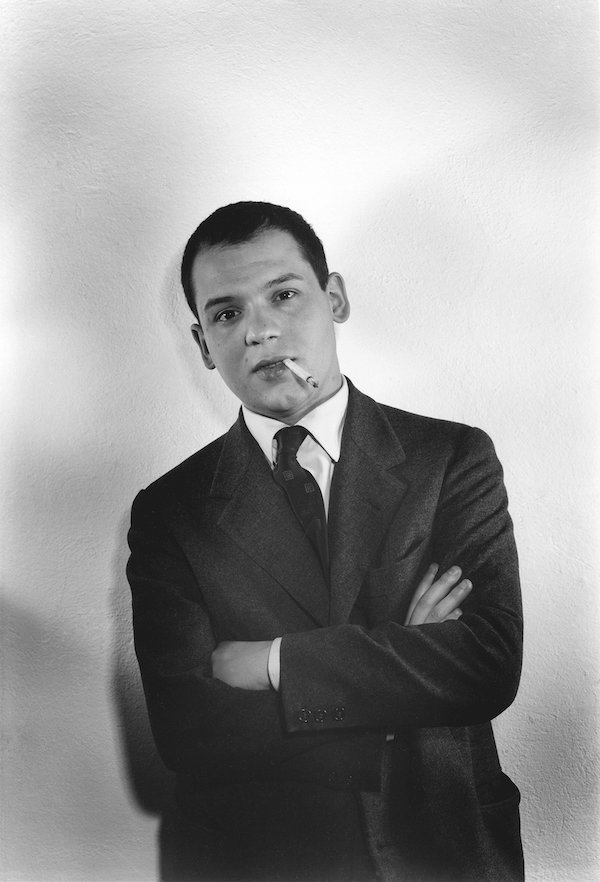

Piero Manzoni portrait.

An encounter with the Yves Klein’s monochrome paintings focused him on his next step: achromatic paintings. His first show of mature work occurred in 1958. The burst of creativity that occurred during those few years until his death in early 1963 has influenced many an artist that followed. Until now, the person behind this body of work has been invisible and mysterious in the anglophone world. The book does a lovely job of explaining the sequence of events during those years, as well as how one work led logically to the next. It also does a great job of providing context for how Manzoni’s projects fit into Italian art, and the greater art history narrative.

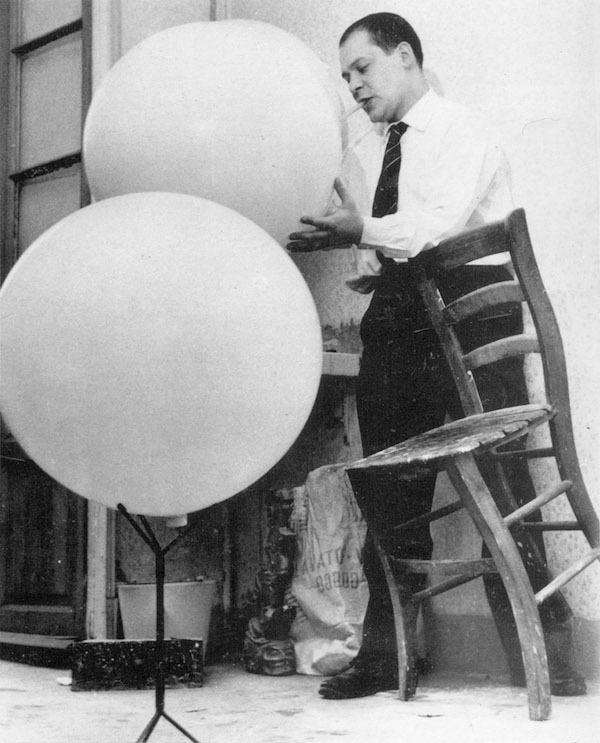

Piero Manzoni, “Art Shit”

The book itself is a lavish object. It’s printed on thick deluxe paper that allows reproduction of color plates within the text. These color plates include diary entries, rare candid photos, show flyers, early work and the stuff that doesn’t fit in monographs. The bibliography is extensive, and might convince a devoted fan to take Italian lessons. The translation of the text (originally released in Italian in 2013) does an excellent job of conveying some very complex concepts as a very readable tale.