The 22 representational paintings, drawings and prints comprising Vincent Valdez’ show, “It Was Never Yours,” symbolize American decline and apprehension with varying degrees of overtness. The Houston-based artist’s occasional flirtations with obvious content, such as presidential portraits or a stormy seascape, are redeemed by his nuanced manner of painting; technical virtuosity sets off his premonitory intimations of sociopolitical decay.

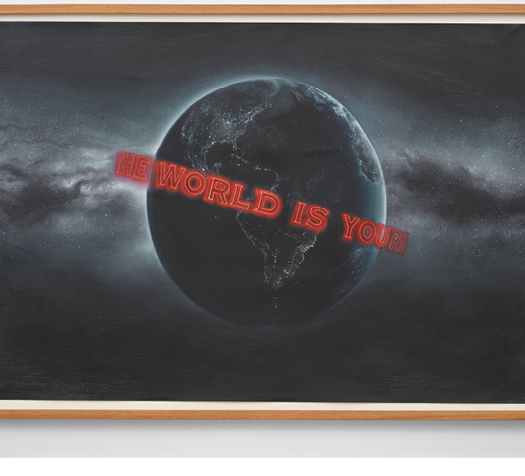

Resembling Universal Studios’ logo, the show’s eponymous painting, It Was Never Yours (2019), features a black-and-white satellite view of Earth ringed by red neon signage proclaiming, “THE WORLD IS YOURS”. With its title cynically rejoining the assertion of its depicted text, this painting reads as a critique of Hollywood’s ersatz rosiness.

In Rise (2019), a pile of rubble appears as a purple mountain phantasmally backlit by the low sun burning red-orange through gray haze. In a different painter’s hands, this stark image might appear boring, but Valdez animates the scene, shading and individualizing each rugged chunk of concrete in contrast with the smooth luminous sky. The artist’s Old Masterish style suggests, with an ironic whiff of futility, the ostensible venerability of the past—the same past that led to the current moment where the rubble stands.

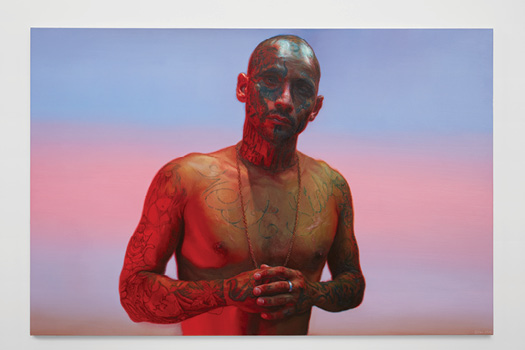

The sunglow in Rise seems to infiltrate the atmosphere of So Long, Mary Ann (2019) directly across the room. This imposing 8-foot portrait elicits a peculiar mix of empathy and apprehension. An inked tough leans shirtless toward the viewer, his hands clasped in a conciliatory gesture, his faraway gaze glinting with sadness. The vulnerability suggested by his pious bearing seems at odds with the grit attested by the tattoos covering his arms, head and scarred chest. Perhaps the indelible adornments serve as symbolic armor expressing on his body what he will not say in words; the press release indicates that they commemorate the loss of his mother, but his identity is left anonymous. Although this painting is not a self-portrait, one wonders if it might also express something personal to Valdez.

On the adjacent wall is “Since 1977,” a sequential row of wryly cropped portraits depicting the upper cephalic portion of each president having served since the artist’s birth year. Beginning with the top half of Carter’s face, the proportion of visible pate sinks progressively with each president until only Trump’s wigged crown remains. The final frame beyond is pitch-black.

The show’s denouement is Eaten (2018-2019), a monumental monochromatic painting of a monstrous hog ominously surrounded by partially chewed human articles in a wasteland. A person’s hand and foot protrude from underneath the porcine corpulence; are human and swine morphing into one, or could the pig be trying to conceal the body of someone he has killed? Valdez modeled the boar’s face loosely after that of J. Edgar Hoover, casting a paradigm of legal authority from the past into a futuristic Armageddon of misgovernance where few spoils remain for the hogging. Eaten II (2019), a bevy of painted bronze sculptures resembling singed crumpled paper, litters the gallery floor, bringing the swine’s devastation into the real world.