When the Long Beach City College Art Gallery invited Cheri Gaulke to show “Peep Totter Fly” alongside Michael Arata’s “Texas Style Beauty Contest—Miss M,” she initially recoiled. “I wasn’t quite sure where he was coming from,” she remarked in regard to Arata’s carnival-esque work. During the three-week run of both shows that ended April 28, Gaulke quickly warmed up to Arata’s work, and both found themselves similarly sympathetic to oppressed or ostracized female voices.

“I thought physically the two shows worked so great together, they both had this visual idea of repetition, and things on the wall that worked really well,” Gaulke commented, referring to her multiple pairs of red high heels on floating shelves along a wall, and Arata’s cluster of red-lipped smiles hanging on the same wall, on the other side of a divider.

Gaulke’s wall of shoes

Gaulke’s heels, displayed in ascending size order as they might be in a store, and Arata’s wide grins, amassed with other playful colors and forms, evoked familiar, leisurely excursions: a day of shoe shopping, and a day at a carnival. By beckoning people into these familiar benign escapes, both works encouraged visitors to dive in as participants without fear or inhibition, and thereby undergo a shift or transformation that would ultimately leave them advocates against the activity in which they had so blithely participated.

Accompanying Gaulke’s shoes was a looping video of feet in the same man-made heels, trekking across starkly contrasting natural terrain that spanned soil, sand and rocks. The wholly vacant floor beneath the screen and shoes was a spacious invitation to visitors to try on a pair of shoes and walk around. On the interactive nature of the work, Gaulke contended, “If you’re just on the outside, judging it as this aesthetic, you don’t have that kind of self-knowledge about what it is.”

Gallerygoers try on Gaulke’s red heels.

“I feel we have this cultural blind spot where we don’t see [high-heeled shoes] for what they are,” she continued. “Let’s say we’re all walking around in flats for hundreds of years, and somebody says, ‘What if we get this skinny little point and stick it under our heel, and elevate, and we’re going to walk around like that.’ You’d be like, ‘That’s ridiculous.’ [Yet now] nobody sees how silly it is.”

Go ahead men, see if the shoe fits.

Gaulke wanted men in particular to experience the absurd discomfort of the shoe firsthand, as she traced the popularization of the high-heeled shoe to King Louis the XIV and found it ironic that men have since abandoned the fashion. “They don’t last long,” Gaulke remarked of the men in the heels. “It starts out like a fun challenge, like walking on a tightrope or riding on roller skates for the first time. Then you start to go, ‘Oh wait, this is stupid, this hurts, this is awkward.’”

The shift in some males’ perspectives on whether females should wear high-heeled shoes happened within the span of their short, intentional walk in them. Gaulke, who teaches at Harvard-Westlake School for grades 7–12, involved several of her students in creating this work. “They went with me up to Death Valley to shoot and were some of the people who wore the shoes in the video,” she explained. She noted that afterward “a lot of the straight boys told their girlfriends, ‘Don’t wear high heels for me, really, because they’re not even comfortable.’” This shift in male thinking was one kind of transformation Gaulke sought through her work. “Bringing them into the conversation [through direct participation], they can become advocates,” she said.

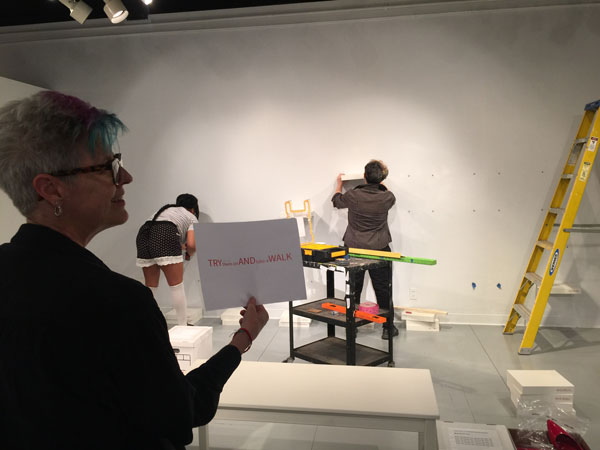

Cheri Gaulke in the foreground.

Gaulke’s feminist thinking predates her personal and artistic obsession with shoes by several years. “I remember my first feminist thought when I was four, when I came into the consciousness that the two things in life I wanted most I couldn’t have because I was a girl,” Gaulke relates. “One was I learned I couldn’t [always] be a Gaulke because girls got married and had to change their names, that bothered me. The second thing was I really wanted to be a minister like my dad, and I found out that girls couldn’t be ministers. So I felt this deep sense, as a very young girl, of injustice in the world based on gender. All the work that I do is very much about giving voice to the voiceless, and it’s rooted in that sense of myself as a female living in a patriarchal society in which being female is not equal to being male.”

In a prior stop-motion animation piece for Artemisia Gallery in Chicago, Gaulke depicted the liberation of a female foot, where binding and a high-heeled shoe eventually tear off of their captive foot, enabling the ankle to grow wings and the foot to soar into the air. “Peep Totter Fly” alludes to a parallel transformation. “It’s a bit of a play on words, with women as ‘chicks:’ you’re born, you peep; you totter as you learn to walk; and then you ultimately fly. So for me it’s kind of a metaphor for transcendence,” she reflected, elaborating that shedding a preoccupation with maintaining balance on tiny stilts allows women to engage more fully in the present moment. “I keep thinking, ‘I’ve done my final piece on this theme,’ and I’ve found that it re-emerges.”

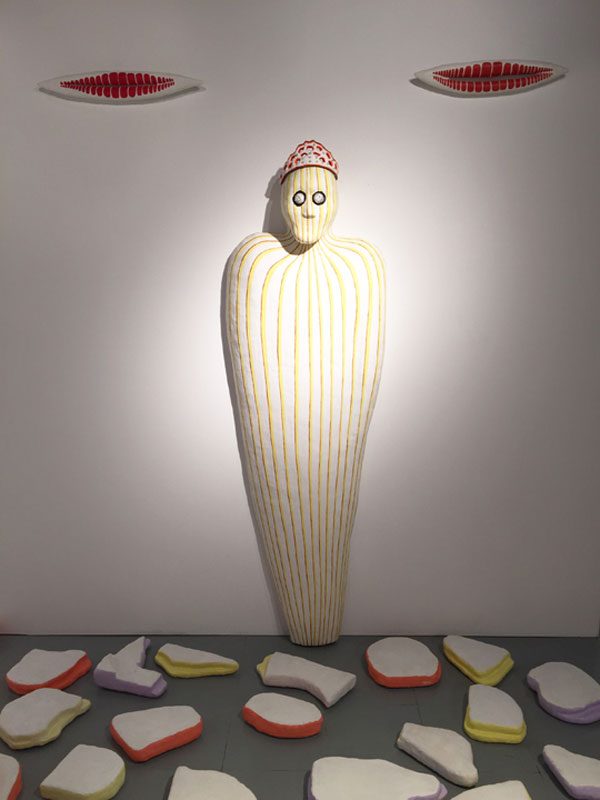

Arata’s installation.

Through a narrow passageway and on the other side of the gallery divider, a cotton candy-colored array of slugs, smiles and Styrofoam stones welcomed visitors into Michael Arata’s exhibition.

“It’s stuff that just pops up on my browser,” Arata explained of the inspiration he often uses for his work. “That’s where this show came out of, an article that popped up when I opened my email,” Arata continued, referencing an article in the Houston Press titled, “10 Hottest Women on the Texas Sex Offenders List.” “I got shocked, and ran with it,” he said.

Michael Arata’s crowning touch.

While Gaulke’s installation grew out of a persisting commitment to righting gender inequity, Arata’s work spoke to gender in a more incidental and stream-of-consciousness manner; but a strong shared impulse between the installations was to upend absurdity. Arata challenged the deranged logic of rating female molesters’ attractiveness by creating a theater for a pageant where the winner would be crowned “Miss Molester,” but where beauty would not be detectable. Visitors could only observe the series of molesters’ faces as upright blurred photographs and inverted muddy paintings. “The whole concept of someone sorting through the incarcerated molesters and rating them in a beauty contest was just such an upside-down concept to me—there should be no reward. So [the faces] are turned upside-down. And they’re blurred because I didn’t want you to really look at their faces for the beauty,” Arata explained.

Michael Arata, Perps and Scars.

Flanking the series of unrecognizable faces were scars several feet long, resembling fanciful pink slugs. “They’re meant to be the representation of the social scars that come with being the victim of molestation, and the molester,” Arata stated, suggesting that the stigmas of being either the victim or the molester become amplified and distorted into jokes through gossip.

Such gossip was embodied in the dark horizontal slivers hanging on one wall, wrought from the negative spaces between the hanging smiles. “Those [slivers] are whispers, those were about rumors,” Arata said. Ultimately, then, while the work was born out of the absurdity of a 10 best list of female molesters, it meandered and reshaped itself into a critique on the consequences of being ostracized through rumor and shaming. The real-world terminus for Arata’s roving disapprobation was the stoning of female rape victims in the Middle East—an ultimate form of shaming and ostracism. The pageant stage was indeed littered with large white stones bordered in pastel colors (“Pastels made sense to me for female molesters,” Arata said).

Michael Arata, Boggy Queen.

Just as Gaulke determined that direct participation was necessary for—particularly male—visitors to have a transformative experience, Arata created a theater encouraging visitors to engage in a stoning, affording them the opportunity to innocuously yet fully assume the mob mentality that perpetuates such brutality. In an earlier work called 1:1 Ratio involving 100 brown glass bottles hanging from wires, each bottle bearing a large drawn eye, Arata presented visitors 100 white rocks and said, “If you can leave everything alone, then we have perfect peace and harmony.”

“I indicated that the bottles represent brown people,” Arata continued. “Because it was like the idea of throwing darts at balloons at a carnival, people picked up the rocks and threw them and broke all the bottles, shattered them. It was a representation of what mob frenzy was like, because that’s how it escalated. People were overjoyed with breaking the bottles: “I got one!” That kind of thing. We turned it into a perverted kind of game.”

In the same way, in this candy-colored carnival-like arena, the “psycho smiles,” as he calls the hanging smiles, and their corresponding rumors, tower above the stage and egg on the stone throwers as if the event were a game. Surprising savagery is unleashed in the visitors as the stone-throwing escalates. While Arata is more sympathetic to the scenario where the victim of molestation is the target of stoning, he believes the molester as the target of stoning would be worthy of sympathy as well, since he views stoning on its face as an extreme violation.

Arata’s impulse with gender in his prior work has been to level the playing field by reversing what he views as “stereotypical gender activities,” but he eschews being labeled a feminist. “I grew up with feminists and the feminist attitude for so long—there’s kind of a militaristic quality about it, and I’m not so interested in the militaristic stuff. I’ll work with it, but I don’t call myself a feminist.” He adds, “I wouldn’t call myself a male-ist, either.” He prefers to allow people to be however they wish, whether or not it aligns with an ideology. “I am absolutely okay with women who want to be sexually attractive to men in a way society says they should—that’s fine. As long as they know what they’re doing, it’s really about them being happy. Nobody should feel ashamed for being who they are.”

Michael Arata amid his installation.

Arata is currently “making dogs and cats,” and creating paintings of myriad spam emails that curiously land in his inbox. None of these projects relate to gender; but if another gender-related headline or spam message pops up, he may decide to pursue it. “I’m not seeking gender issues,” he remarked, “but they’re so obvious—it’s something I can’t resist or deny because it’s in front of us all the time. When it gets to the point where it’s not, then I won’t have to do any of this because it won’t be an issue.”

Long Beach City College