“Can you smell the earth exhaling? I love the smell of moisture coming out of the ground,” exclaims artist Jessica Taylor Bellamy, inhaling the sweetness after the drizzling rain as we embark on our Sunday afternoon hike through the wetlands of South Los Angeles. As we descend the muddy hillside draped in bright yellow wildflowers, we share a moment of childhood nostalgia, recalling wild mustard flowers that flourished vividly in our memory. Looking down at the soles of my sneakers, already caked with dirt, I feel a sense of wonder, enchanted by the green, dewy world before me, as if I were 10 years old, my clammy hand nestled tightly in the palm of a friend.

Bellamy and I met as graduate students at USC in 2020. Our friendship blossomed around our shared interest in ecological theory, Mike Davis, Octavia Butler, and growing up in Southern California in the Y2K era. Our conversation about LA, art and ecology is ongoing and personal—it is an ever-evolving dialogue grounded in friendship and a mutual desire to care for the planet.

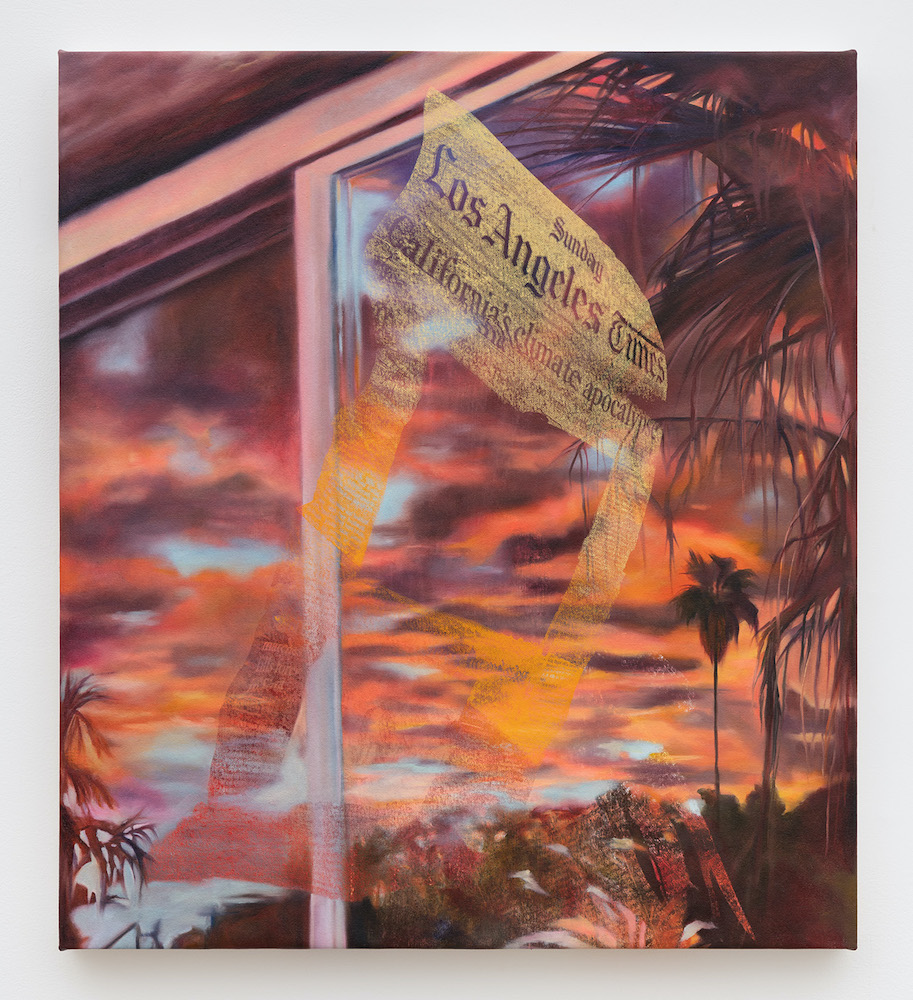

Guided by eco-phenomenology, Bellamy’s work is informed by the city’s shifting environment and ecological entanglements, her experiences, observations and familial history. The artist’s prolific practice spans painting, screen printing, film, sculpture and installation, all of which incorporate observational and scientific research, found images and a well of archival materials she has developed throughout the years. While her approach often involves figures and data, it is also experimental and poetic. Many of her paintings incorporate found text from popular media sources such as the Los Angeles Times hand-screenprinted onto her paintings, resulting in juxtapositions that expose tensions embedded in the city. Myths of sunshine and noir collide in her beautiful, almost sublime renderings of the California landscape overlaid with headlines about social and environmental devastation—situating her practice in a specific place and time.

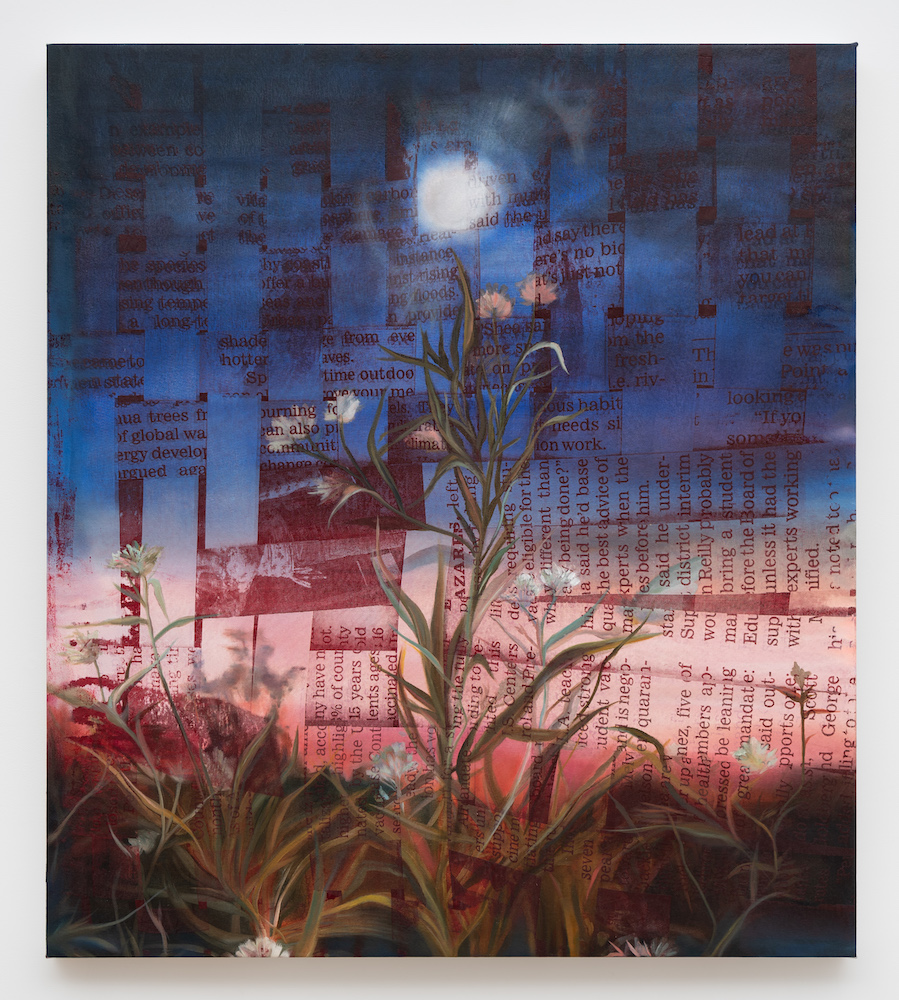

Jessica Taylor Bellamy, Proving Ground, 2023.

Our conversation took place in and around the Ballona Wetlands Ecological Reserve, located just down the street from Bellamy’s home in Playa del Rey and a short distance from where I grew up in Palos Verdes. With hundreds of acres of salt and freshwater marsh, the park’s meandering terrain feels both contrived and unruly. It exists in a constant state of construction and repair in coordination with the Ballona Wetlands Restoration Project (BWRP), which aims to reconnect the land and the sea, allowing fresh and salt waters to flow and support a healthy ecosystem.

“People don’t realize there is actually nature in Los Angeles; you just have to know where to go,” Bellamy states as she points toward a thorny vine of wild strawberries crawling along the trail’s warped wooden fence. The sound of bugs and critters trilling around us resembles a pulse—life and earth percolating with rambunctious vitality. White egrets graze elegantly at the water’s edge, seemingly unfazed by the flight path overhead or the sound of traffic from surrounding intersections. It’s as if the egrets decided to tune out the buzz of the city. This entanglement of life and death (human and nonhuman) and environment (built and natural) exemplifies the collaborative ecological thinking at the heart of Bellamy’s practice.

Bellamy points up at two hawks soaring across the murky skyline. She always seems to know when a hawk is nearby. Various animals and plant life operate like symbols in her practice, taking on particular meanings relating to the artist’s identity and environment. Hawks can be found throughout the artist’s work and tell a story about her father, who immigrated to California from Cuba in the late 1960s and eventually settled in Inglewood, where he learned to train red-tailed hawks to catch mice and other small critters. Bellamy has become attuned to the strange spaces where nature and culture interact.

The mud beneath our feet grows stickier as we travel deeper into the wetlands, the dirt telling our bodies to slow down and look. “Los Angeles is an ongoing construction site,” says Bellamy, as we stumble upon a fence that appears to be sinking into the muddy water. Crooked and nearly half-submerged, the fence looks silly and trite, like an artificial boundary for the mouth of the marsh to swallow, for nature to devour. This image recalls the many variations of screens and portals that appear in Bellamy’s work—found and imaginary, natural and artificial. A recent painting titled Floods in a Desert (included in the artist’s inaugural exhibition with Anat Ebgi gallery) depicts a window that is warped by the ghostly impression of a Washingtona robusta leaf (Mexican fan palm), further abstracted by layers of cracks and fragments that resemble broken glass. Rays of kaleidoscopic light seep between the layers of reality, refracting and deflecting to further distort any sense of perspective. This underlying menacing beauty evokes the paradoxical feeling of living in Los Angeles. Bellamy exposes the tensions built into the city and considers how they are amplified by the clash of fantasies, mythologies and realities.

Jessica Taylor Bellamy, Ignorance and Nothing More, 2023.

“We’re almost near the crazy-ass birds!” Bellamy announces with an eager giddiness, hurling her finger into the air to guide my eyes across the water toward a pair of resident Canadian geese that stand charmingly side by side at the edge of the marshland. She explains that they are grounded in the wetlands due to the disruption of their migration patterns, like nonhuman climate refugees. These geese make me think of agency (and oppression) from a multi-species perspective.

Bellamy reminds me that the LA wetlands undergo “rewilding” every year in an effort to remove invasive species that could potentially disrupt the ecosystem. The following stream of questions arises: What makes an invasive species invasive? Do invasive plants and critters have agency? Or is their invasiveness just a mode of survival? A reaction to their forced displacement? Should we consider ourselves (humankind) an invasive species? After all, aren’t we the ones choking the climate to death in the name of “progress”? Agency shifts and falters with every collision and collaboration or, in Karen Barad’s words, “Existence is not an isolated affair.”

Bellamy tells both macroscopic and microscopic stories about agency and oppression, collected and constructed from her lived experience and intimate observations. She helps instruct us on how we might feel the ground exhale.