Nestled on the ground floor of an academic building on Pitzer College’s campus, the Lenzner Family Art Gallery is easy to miss. Its layout is as humble and curiouser still: an L-shaped room is flanked by two alcoves too small to be rooms and too large to be closets; the ceiling feels low, and the perpetual whir of air conditioning permeates the space (“It’s always on,” says Chris Michno, the gallery’s Exhibitions and Communications Manager). Jolted into a heightened awareness of one’s body in this setting, one asks, “Am I really in a gallery—what did it used to be? What could it be instead?”

Here, where our assumptions about public places are spotlighted and disrupted, Ashley Hunt presents Degrees of Visibility, a deceptively understated collection of photographs, drawings, maps, activist ephemera and other objects documenting and resisting what he terms the aesthetic regime of the prison industrial complex in the United States. “The prison industrial complex is a system of things we think of properly as prisons and jails and detention centers,” Hunt explains, “but also different regimes of policing, border security, surveillance, probation and parole systems, and the multiple economies that exist around and between them that form a carceral system. We think prisons bring justice to crime victims and have the possibility of healing [or] bringing peace to anyone and are essential for safety. But I see it as a sprawling system of relationships through which the dominant orders of Western society are maintained—so, colonial relations, dehumanizing relationships, relations that extend out of slavery, indigenous dispossession and imperial expansion, gender controls and normativity, and labor exploitation and politics. I think these are all part of the dominant order the system is really there to preserve, and is doing less and less of a good job at.”

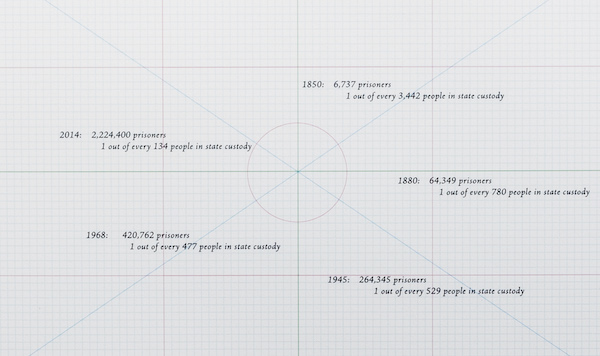

Timeline

With the highest numbers of, and exponentially increasing, prisons and imprisoned or detained people per capita, the U.S. presents a panoramic manual for the propagation of prison systems within and beyond a country’s continental borders. In the last nine years, Hunt has taken from publicly accessible vantage points over 260 photographs of sites containing prisons and detention centers across all fifty states and territories, where all carceral buildings—whether through occlusion by natural or manmade structures, remoteness, or appearing as something other than a prison—bear strategic facades reflecting local politics. Arranged in the gallery like stanzas of a poem—grouped, for example, in twos, threes or fours, clipped provisionally onto plywood or matted and framed, hung on a wall or angled alternately on the floor in call-and-response style—roughly half of Hunt’s total photographs are included in this exhibition, curated by gallery Director Ciara Ennis. Each of the show’s twelve iterations has featured different images and arrangements reflecting respective venues and local politics; these evolving poetic presentations echo the perversely poetic way in which the prison industrial complex, or PIC, has ramified throughout the country, adopting variegated camouflage to infiltrate diverse milieus.

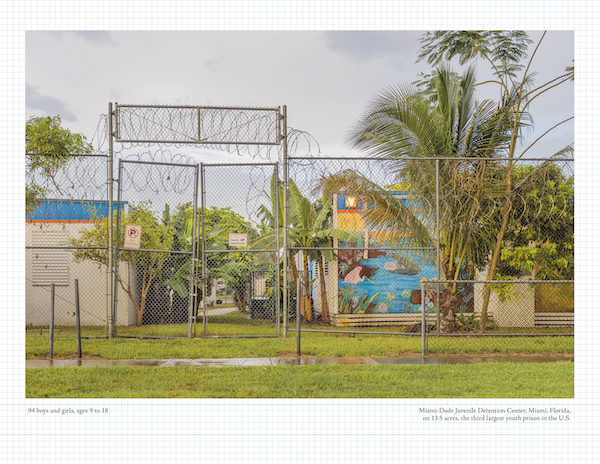

94 boys and girls, ages 9 to 18, Miami-Dade Juvenile Detention Center, Miami, Florida, on 13.5 acres, the third largest youth prison in the U.S.

The overarching aesthetic strategy of the PIC adopts twin tactics of normalization, where both peddle optical illusions tied to circular logics. The first tactic makes prisons blend in with their environments or appear commonplace; through outwardly resembling schools, civic centers, corporate office buildings or even grass-covered hills, prisons deter us from examining their interiors (of stacked human cages). The Miami Dade Juvenile Detention center in Florida bears a cheerful mural behind swaying palm trees and a towering barbed wire fence; without any signage indicating its purpose, we can only infer by its mural that the site is for children. Yet, as fences, cameras, guards and metal detectors in and around public schools and other institutions have become commonplace, the “Security Cameras In Use” sign on the fence legitimizes rather than red flags the site, and we walk by without further questions. The penetration of public places by carceral practices like surveillance systems points to normalization’s viral and circular operation: as prisons steal the facades of other public institutions, other public institutions absorb prisons’ tools of control and punishment. Thus, the PIC burgeons through conflation and consolidation, and we barely bat an eye at the lyrical sleight of hand whereby a former Walmart—emblematic of the exploitation of undocumented migrant workers—becomes a migrant children’s detention center at the U.S.-Mexico border.

1,469 children imprisoned in a former Walmart as ‘unaccompanied minors’ and children separated from their parents, Casa Padre Facility, Southwest Key Programs, Brownsville, Texas

The PIC invokes oppressive normativity as its second tactic of normalization. Through allusions to scientific or natural social orders justifying the isolation of certain categories of people—diseased, insane, homosexual, nonwhite, degenerate, or otherwise deviant—from society proper, prisons have been allowed to proliferate; in turn, by virtue of appearing commonplace, prisons seem to reflect natural or inevitable social orders. Again, a circular logic—that seduces a public standing at either end of the argument into accepting it as a truism—emerges as a hallmark strategy of the PIC in manufacturing political consent.

Hunt deftly captures the PIC’s deployment of normativity in his layering of visually understated landscape photographs and captions against equally quotidian grids and plywood backings. The raw plywood boards speak to naturalness and guileless candor, while the gridded paper “came for me as a reference to field notetaking, somewhere between that and architectural renderings and rational grids,” Hunt notes. Hunt’s formulaically conventional landscape photographs—employing the elementary rule of thirds, for example, or centering prisons or other structures where we would expect to find a photograph’s subject—invoke a repetitive visual—and ideological—syntax. Articulated through camera lenses Hunt describes as “at the edge of a wide field of view before bending off into distortion, or at the edge of a natural-seeming angle of view,” this visual syntax generates an undistorted, seamlessly continuous and ubiquitous narrative that points to a comfortably familiar and sustainable way of life that need not be questioned.

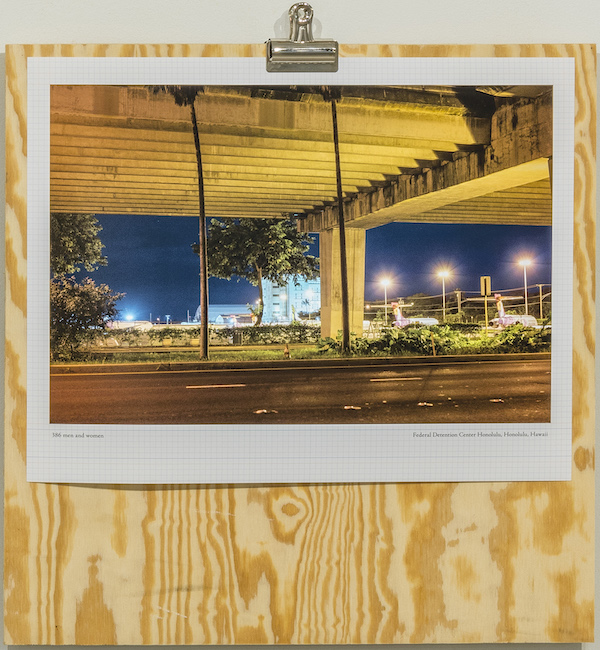

386 men and women, Federal Detention Center Honolulu, Honolulu, Hawaii

Taking visual dictation of what appears in plain view is referenced by the layering of photograph, grid and board, as is surveying land and recording scientific data, all alluding to the PIC’s ostensibly honorable practices of observing, planning, designing and building around self-evident natural phenomena such as landscapes and categories of people. At the same time, the imposition of the net-like grid on the untreated board suggests a more ominous impulse to capture and striate the untamed or wild. In so presenting poetic propositions where optics and meanings are densely layered, Hunt exposes the PIC’s aesthetic tricks of selectively framing and amplifying appeals to rationalism, naturalism and classification systems while diminishing or erasing detained people and the violence inherent to their detention. Inducing hypnotic persuasion, these manipulations mask while replicating a racialized agenda of control. “The ideology of criminal justice today is unquestionably the ideology of race, itself disguised as another science,” Hunt argues.

To escape the caging circularity of the “normal” conditions of our present, radical alternatives must be seen or imagined; in the same layered gestures through which he unveils the PIC’s strategies, Hunt, fortunately, points us toward a way out. “The primary poetic gesture of the work,” he offers, “is the juxtaposition between the landscape photograph and the number of people you can’t see but who offer another description of that space; the contradiction between what the image does and doesn’t show and what that number does and doesn’t tell is where I think the main poetic energy is.” Indeed, the counting and labeling of incarcerated people in both a conventional font and position below the image contours and flattens incarcerated bodies in a holographic or alternating manner. On one hand, we recognize the presence of distinct human beings although none are in view and decry their imprisonment. On the other, as quantitative captions were taken directly from prison websites, we read the PIC’s matter-of-fact designation of an othered group of people as uncontestable reportage; these others or “criminals,” we figure, ought to be put away, and the faint squares of the grid referencing jail cells help effect a clean, visually palatable erasure of the reality or even idea of cell occupants. In presenting competing dignifying and disappearing interpretations, Hunt forces us to acknowledge that both are operative at once, and that we, ultimately, are responsible for what we see—first in our minds, then in our world.

Blindness to our complicity in perpetuating the PIC has historically netted the progressive impulse to fall in line with normalization and “improve” prisons by making them “more normal.” “There’s a discourse around normalization in the sixties and seventies which was about trying to have carceral spaces feel less brutal, less austere,” Hunt notes, alluding to reform efforts aimed at softening prison conditions and treatment of prisoners, rather than the more radical alternative of eradicating prisons and punishment-based systems altogether.

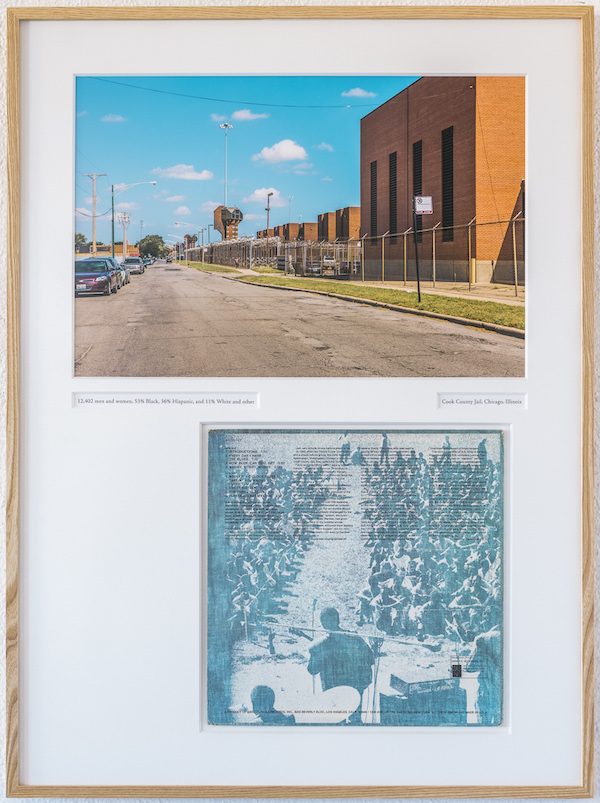

12,402 men and women, 53% Black, 36% Hispanic, and 11% White and other, Cook County Jail, Chicago, Illinois

Referencing one of his more distinctive framed pieces featuring the back cover of the B.B. King album, “Live at Cook County Jail,” Hunt explains, “The B.B. King concert [in 1970] is one of the more famous examples where musicians and artists went into prisons to do concerts in solidarity with prisoners around that timeframe. Reform-minded wardens would say, ‘We can have a concert for the prisoners.’” The concert crowd spanning the back cover points to, Hunt muses, “spectral bodies referenced only through numbers or imagination in looking at the [landscape] images.” While Hunt acknowledges that reform efforts have amplified the dignity of prisoners, he contends they do not go far enough; on this cover, he notes, the imprisoned bodies are “still very faint.” “More harsh and draconian treatment was reinstituted in the eighties and nineties,” Hunt observes, pointing to the fact that a fundamentally dehumanizing system only affords oscillating degrees of dehumanization.

When prisoners’ consciousness around the conditions of their imprisonment became too heightened, counterinsurgency architecture developed to reinforce normalization strategies and the PIC’s dominion. “One of the other histories of erasure came in response to the many rebellions within prisons of the sixties and seventies where prisoners were able to communicate with each other, organize, consciousness raise [and where] support systems outside the prison were able to grow,” Hunt notes. “Those all became threats to the system when they became articulated along the direction of social change, and that’s when you start to see the creation of permanent solitary confinement with supermax prisons and control units, keeping prisoners from communicating or knowing where they are, even. Around those kinds of prisons there’s more secrecy, more locating them farther and farther away from urban centers, making them hard to get to [and] further destroying families.”

683 women and men, Metropolitan Correctional Center, Chicago, Illinois [partial view]

At an extreme, castle motifs are instituted, manifesting the rhetoric of empire and war that underlies not only counterinsurgency architecture but the agenda of the PIC as a whole. Hunt observes, “Every big city has a federal prison, and they have a fairly unified architectural language that is erased of the historical signifiers of punishment we’re used to seeing, but that look like, at the same time, brutalist fortresses.” Sliver-width windows, like those of the Metropolitan Correctional Center in the heart of Chicago, “come from castles and fortresses,” Hunt notes; his longer plywood boards and a framed horizontal piece containing multiple images reflect this narrowness. Rather than keep enemies out, Hunt further notes, penal fortresses like the Kentucky State Penitentiary, dubbed “the castle on the Cumberland,” are designed to contain enemies, particularly those likely to incite rebellion.

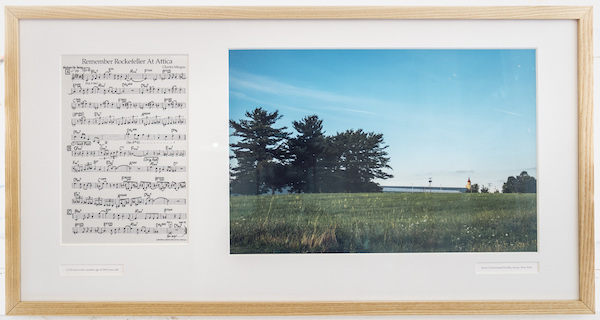

2,152 men with a median age of 38.4 years, Attica Correctional Facility, Attica, New York

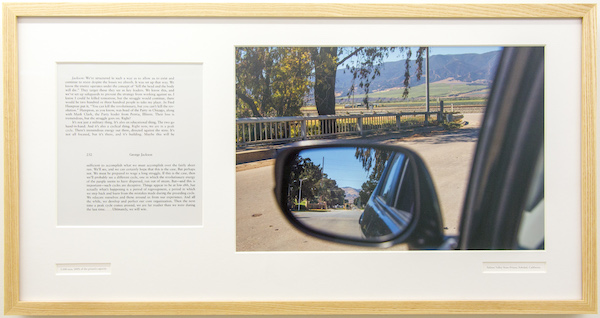

Several pieces acknowledging prison uprisings and their interlinked histories showcase text or information exceeding quantitative captions. Hunt commemorates the 1971 rebellion at the Attica Correctional Facility in New York with the sheet music for Charles Mingus’ “Remember Rockefeller At Attica,” mourning then-governor Nelson Rockefeller’s deadly decision to quash inmates’ demands for humane treatment by calling in the National Guard. Beneath his photograph of cotton fields surrounding multiple prisons in Atmore, Alabama, Hunt narrates an extended history of racism and forced labor culminating in a national prison strike organized by inmates in 2016 that commenced on the 45th anniversary of the Attica riots. Alongside a photograph of Salinas Valley State Prison in a car’s sideview mirror, Hunt excerpts a 1971 interview with former inmate George Jackson, whose extensive activist writings and work were germinal to the Attica uprising; we note this interview excerpt challenges the prison image in size, as do letters placed beside images of other prisons where the respective writers were detained. These spoken words, letters, sheet music and Hunt’s expanded histories build up a chorus of uncensored consciousnesses, resisting with at least equal strength their oppression and creating an alternative network. Beyond reorienting our vision, thus, Hunt invokes vocalization to counter the PIC’s silencing, and we become increasingly embodied in relation to the work.

3,168 men, 160% of the prison’s capacity, Salinas Valley State Prison, Soledad, California

In placing us in the driver seat through his framing of the sideview mirror, Hunt further causes us to be embodied and mobilized; as sideview mirrors come with the alert that “objects in mirror are closer than they appear,” we intimately and viscerally gauge our personal proximity and relationship to what is reflected on our path. The framing of the prison in a rearview mirror also highlights the backward-looking trajectory of the PIC, where what lies ahead reflects and repeats what came before. “One of my last works before this was on the impacts of Hurricane Katrina on New Orleans,” Hunt reflects, “which in many ways was about erasure—the disappearance of whole communities subject to the incredibly corrupt and racist criminal justice system in that city. Degrees of Visibility evolved out of a shift in my photography from describing what prisons look like, to describing how they’re hidden, creating an encounter for a viewer with that disappearance that wasn’t about the state of emergency that follows a disaster, but a sustained, continuous catastrophe that extends so far backwards.” While the reflected prison might be interpreted as inescapably following us forward, it can also be viewed as something we are leaving behind.

Installation view at Lenzner Family Art Gallery, 2019

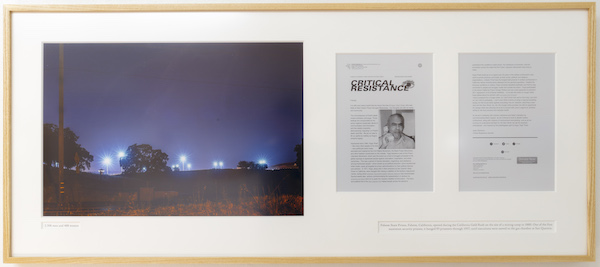

Our embodied agency in interpreting and responding to our environment is further ignited by the alternation of frames and clipboards throughout the gallery, where once again competing interpretations afforded by conventions are brought to our awareness. Framed gallery pieces are not to be touched, but clipboards are meant to be handled; we are further tempted to swap out photos on boards with some of the scores of loose prints on shipping crates in the center of the space. In omitting instruction as to whether anything may be handled, Hunt subdues the authoritative artist’s intention and activates our own. Yet, he does not remain neutral; as we circulate the gallery, mesmerized by imagery, our steps are disrupted not only by shipping crates indicating physical and far-reaching mobility, but also by activist ephemera and takeaway newspapers on the floor highlighting community gatherings and conversations resisting the historical erasure of organized bodies in dialogue. Usurping or reclaiming the quotidian aesthetic coopted by the PIC, these grassroots activities redirect focus from optical illusions onto human bodies, enacting a new normal or commonsense vernacular rooted in community-based care rather than punishment.

Having reenergized our sight, voices, and authority and ability to act through his artwork, Hunt invites visitors to participate in a ten-part conversation series on abolition scheduled through December 7 throughout Southern California, co-organized with artists and activists Silvi Naçi, Kenny Crocker and Jess Heaney. Reflecting his most extensive programming series to date around this work, Hunt and his team partner for this iteration with longtime collaborator Critical Resistance, California Coalition of Women Prisoners, Californians United for a Responsible Budget, Starting Over, Inc., All of Us or None, Interfaith Movement for Human Integrity, NAVEL, Southern California Library, the Women’s Center for Creative Work and Claremont Colleges Prison Abolition Club, among others.

2,306 men and 488 women, Folsom State Prison, Folsom, California (diptych with obituary of Hugo Pinell)

As distinguished from prison reform, abolition seeks not only to abolish prisons and punishment-based systems, but to reimagine how public safety is defined and maintained through overcoming what Hunt describes as alienation, and supplanting prisons’ ostensible roles (to hold people accountable and to rehabilitate, heal, or effect peace and justice) with locally-based practices of care rooted in listening to and addressing the histories and needs of those most impacted by the PIC. “All of the rhetoric around the ‘tough on crime’ movement since the late sixties in the U.S. has been this way of disappearing the reality of racism, classism, sexism and homophobia in our society behind a language of individual choice and weakness and failure, that totally alienates—and by alienates, I mean detaches the relationship in our minds and perception as to how social forces overwhelm people and how history lands on communities,” Hunt explains. “It might appear that it’s one person’s choice to wind up harming someone, but that doesn’t tell you anything about the larger social backdrop against which those choices become reasonable or the only choice. Whole economies that are black market economies have literally sustained communities who’ve been given no other way to survive. And I think the erasure of that historical reality is what we’ve got to get over.”

While even a handful of years ago the idea of eradicating prisons and punishment-based systems in the U.S. seemed politically unfeasible, Hunt and local activists who for many years have combatted plans to construct new jails or legislation aimed, for example, at prolonging detentions and sentences are beginning to witness a tidal shift. Hunt remarks, “What’s unprecedented about right now is getting a county like Los Angeles to recognize that what has been taken for granted for a few hundred years as a rational and effective way to address harm is actually not that. So, LA County’s decision to not build two new jails this year and instead commit to redistributing those three billion dollars to a new infrastructure of care throughout the county on a local and much more accountable level—I think that reflects something of a real kind of change that’s different than ‘fixing prisons.’”

“On Art and Organizing,” public conversation with Jess Heaney, Kenny Crocker and Ashley Hunt, Sept. 19. Photo by Victoria Aravindhan.

As abolition gains traction nationwide through online platforms, its intersection with polarized online opinions on forgiveness, fairness, absolution and accountability (e.g., with respect to Botham Jean’s brother and a judge hugging Botham’s killer, former police officer Amber Guyger, in a courtroom) points to the danger of inadvertently replicating the punishing, ostracizing, flattening and exploitative discourse of the PIC online. “I see the contradiction that comes when one thinks about what possible limitations there are for a social movement that takes place within the same architecture that is set up to surveil and convert us into another form of commodity and raw material to be capitalized upon,” Hunt reflects. “But I disagree with a technologically deterministic view that because that’s where it’s taking place, nothing else is possible within it. A hashtag campaign is limited, but if it’s set up in a way that can take you deeper, that’s great. That’s how I think about art [here], too—if it’s set up so that all you do is look at this work and never have to think about it again, I don’t think it’s really doing all that it can. How can that work help interrupt these economies and histories and habits? How can it support work taking place on the ground that needs additional storytelling and image-making?”

In raising these questions, Hunt unveils perhaps the most invisible lens or point of view operative in his work, pertaining to his own relationship to it. As the poetry imbuing the show alternately reflects the PIC’s manipulations or inmate uprisings, it also undoubtedly mirrors the eye and heart of the artist—sober, haunted, meticulous, and wedded to a relentless and urgent sense of responsibility. “I always ask myself, ‘Who am I to tell this story?’” Hunt admits, addressing the irony or problem posed by his storytelling as a white male around a system that predominately criminalizes, disenfranchises and decimates communities of color. On reckoning and reconciling with his privilege, Hunt reflects, “My privilege affords me access to specific resources, and an inconspicuousness around locations of concentrated power [that] has allowed me to drive throughout the country and photograph prisons and jails and get stopped only one time, without consequence. A mentor in graduate school, an amazing anti-racist and Anti-Apartheid activist, told me, ‘You hear the honest conversations people in certain positions of power would never have around me, and you can help share that access.’ Another mentor, an elder Civil Rights activist, admonished that we ‘take the gifts, skills and talents we have received because of the privilege we have, and sit down, listen and serve.’ Although I have personal stories that have shaped me into one who would do work around the prison system, in no way am I one who is most heavily affected or at risk in relation to it. But that doesn’t mean I have no relationship to it—as one who sits comfortably within the violent fiction of whiteness, I am both the beneficiary of the system’s racism, and, as James Baldwin has taught perhaps most eloquently, impoverished by it. So, I work from a place of responsibility—as a fellow opponent of this system, with the aim to contribute to the knowledge, conversations and actions that help to change it.”

After the Prison, Ruins of the Atlanta Prison Farm

Among all of his captions, Hunt’s description beneath the site that once hosted the Atlanta Prison Farm run by prison labor is the most unusual. On one hand, Hunt’s historical elaborations and tallies of people incarcerated across multiple photographs can be read as memorializing the PIC’s conquests; such a reading is amplified especially where photographs and captions are matted and framed like awards. In a conversation held around a prior showing of this work (transcribed in one of this show’s takeaway newspapers), Hunt discusses with local activists the idea of utopias, where “the utopia of the oppressor” is a “paradise” evincing “perfected forms of control.”

Yet this photo, while using the convention of centering a structure where we would expect to find the photo’s subject, creatively pushes the possibilities of the convention to upend an oppressive reading. The centering of structures, particularly occluded prisons or vestiges of forced labor, not only creates a predictable visual syntax that might render the structures uneventful, but alternatively affords us the opportunity to detect or consider their presences at all, where, were they not centered, we might miss them entirely. Hunt’s lens flare across the center of the former prison farm building yields still another reading: in rending the emblem of oppression with a flash of illumination that both exposes and purges the past, Hunt creates an aperture or clearing for an imaginative new possibility to flourish. This alternative utopia is one of liberation and growth, expressed in Hunt’s foregrounding and cataloging of proliferating foliage. The center of the frame now delivers the radical alternative—a site without prisons—and this reading can be applied to all images in the show where prisons are hard to see.