Your cart is currently empty!

Under The Radar

Ever since 1912, when Picasso and Braque first collaged actual newspaper clippings and trompe-l’oeil woodgrain fragments into the first Synthetic Cubist oil paintings, the confusion between mass media and fine art has been one of the central engines of contemporary human creativity. Two recent art books bring into focus the extravagant range of effects that have been achieved through this dislocation of “high” and “low” image-making—and how powerful such breaches in protocol remain to this day.

The man known simply as Jess (1923–2004) was the quintessential West Coast modernist bohemian, not least for the fact that he worked as a chemist on the Manhattan Project and subsequently abandoned his career in atomic weapons research in favor of a long-term union with the Bay Area poet Robert Duncan and a lengthy, introspective journey as one of the most unjustly overlooked American visual artists of the 20th century—consciously abandoning a tenure-track position in the military-industrial complex for the freedom of radical subjectivity and the love that dare not speak its name.

Jess’ paintings and collages were steeped in the esoteric and occult philosophical traditions that informed much of the proto-psychedelic art of the Beat era, but were equally indebted to the modernist formal innovations of figures like Max Ernst and James Joyce. His oil paint “Translations” appropriated everything from theosophical diagrams to Victorian children’s book illustrations into a curdled, hyperarticulated impasto that comprises one of the most idiosyncratic bodies of painterly investigation of the postwar era.

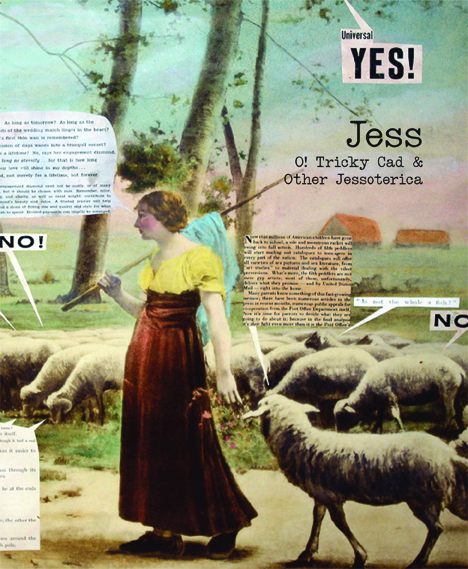

But it is Jess’ “Paste-Ups” that garnered him the most attention, and are now the subject of O! Tricky Cad & Other Jessoterica, edited by LA critic Michael Duncan and published by Siglio Press. The most signal inclusion in this collection is the almost-complete Tricky Cad collages, which, in spite of being Jess’ best-known work, have never been reprinted in one place before.

Often cited as either prefiguring Pop or legitimizing comic art, the Tricky Cads do both these things and much more. Produced between 1952–59, the 8-installment saga, made entirely from cut-up fragments of Chester Gould’s classic newspaper comic strip Dick Tracy, constitute a primer in poetic deconstructionism, reconfiguring the hard-edge graphic semiotics and right-wing bombast of the original into something rich and strange, splitting the atom of normative symbolic ordinance to unleash a torrent of mythopoetic mutation.

Only five of the eight TC collages could be tracked down, but Duncan fleshes them out with an abundance of amazing material, much of it previously unseen. There are several other comic cut-ups, some ribald homoerotic mash-ups of contemporary advertising, elaborate patchworks of old engravings, and even an actual-size reproduction of O!—an entire collage zine from 1960. Proof again that—using only the leftovers of commercial mass media—Jess was making some of the most self-consciously sophisticated cultural artifacts of his time.

The same can’t quite be said for the remarkable hand-painted movie posters from Ghana, collected and promoted by LA gallerist Ernie Wolfe at the tail end of the 20th century. Wolfe’s initial enthusiasm culminated in a stellar 2001 exhibit at the UCLA Fowler Museum with the accompanying Dilettante Press volume “Extreme Canvas”—which soon became a prized collectible, particularly among painters. As exhaustive as that hefty tome seemed, Wolfe’s bulky follow-up “Extreme Canvas 2” offers twice as many examples of these unintentionally avant-garde pictures.

Originally created as advertisements for traveling DIY video

theaters, this peculiar niche medium flourished in pre-digital Ghana, beginning in the mid-’80s and disappearing by the turn of the millennium—except for replicas intentionally made for the folk/outsider art market. While there are many compelling examples flogging Bollywood and homegrown African cinema, the richest vein of material is the painted translations of familiar mainstream American movies—from Raiders of the Lost Ark to Jason Goes to Hell to Jumanji—where the almost Mannerist anatomical distortions and paranoiac attention to the rendering of clothing, hair and musculature add layers of sociopolitical critique to the already convoluted archetypal pictorial content and formal exuberance.

I’ve often heard the argument that so-called Outsider artists are victims of a condescending, exploitative assignment of contextual meaning, but my bottom line is always “What will the Martians think when they excavate the ruins of our civilization in 50 years?” Regardless of intentions, both the extremely individuated, culturally informed works of Jess and the collectively evolved ur-capitalist utilitarianism of the Ghanian poster painters demonstrate how the application of creative human imagination can unlock enormous potentials of conceptual and aesthetic novelty lying just beneath the surface of even the most conventional commercial symbolic language. I don’t think the Martians will see much difference.

O! Tricky Cad & Other Jessoterica, edited by Michael Duncan 192 pages Siglio Press, www.sigliopress.com

Extreme Canvas 2: The Golden Age of Hand-Painted Movie Posters from Ghana by Ernie Wolfe III 488 pages Kesho & Malaika Press 2012, www.erniewolfegallery.com