Avant-garde artistic movements have a funny way of morphing into the mainstream—witness the fridge-magnet ubiquity of Impressionist paintings, or the integral role of appropriated samples in contemporary pop music. Perhaps the least-known but most influential of these absorptions resulted in the dominant mode of 21st-century visual communication—the CGI animation that now fills every movie, TV, computer and phone screen, and will soon be indistinguishable from so-called reality (unless that already happened and we’re actually in a digital simulation, in which case skip ahead).

As is usually the case, the vocabulary and techniques of the avant-garde were cheerfully corralled into the service of far more conventional art forms—action packed superhero movies, for example—and valued for their invisibility: an almost diametrical inversion of the experimental cinematic tradition that spawned them.

The roots of CGI reach back to the beginnings of cinema, and consist of a parallel history of non-narrative, nonrepresentational filmmaking in which the hardwired formalist mechanisms of human optical perception are allowed to frolic naked across the retina, unencumbered by characters, storylines and any but the most musically abstract dynamic arcs. No wonder it’s often referred to as Visual Music!

In the last few decades, a global network of nonprofits have sprung up to preserve and disseminate the legacy of this countercultural current. Two worth noting are the Center for Visual Music (in Los Angeles) and the IOTAcenter, both of which have done a tremendous amount of work bringing attention to the work of such abstract filmmakers as Oskar Fischinger, Hans Richter, Len Lye, Jordan Belson, the Whitney brothers and longtime head of the CalArts experimental animation program Jules Engel.

IOTA recently put the works of one of Engel’s first students—Adam Beckett, who headed the animation division of the original Star Wars—online at Vimeo and Kanopy (where anyone with an LA Public Library card can watch for free). The CVM’s latest crate-digging extravaganza is a DVD entitled Visual Music 1947–1986, which includes restored gems from Engel, Belson and others.

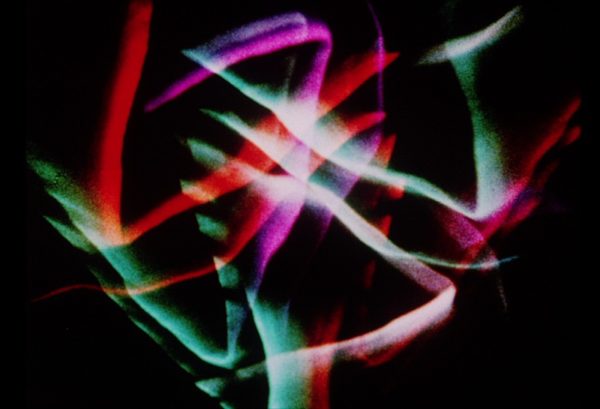

Charles Dockum, 1966 Demonstration of Mobilcolor Projector. (c) Center for Visual Music

All the short films included utilize a variety of pre-digital techniques ranging from the radical DIY of Barry Spinello’s legendary Sonata for Pen, Brush, and Ruler (1968)—produced on a budget of $9 and completely handmade, including the optical soundtrack—to the color organ performances of “illumination engineer” Charles Dockum. The short documentary Demonstration of Mobilcolor Projector (1966) is remarkable in its detailing of the elaborate mechanical craftsmanship that was needed to produce (and record) this time-based visual composition, which—though undoubtedly beautiful—can probably now be rendered with a 99¢ app.

Mary Ellen Bute, Color Rhapsodie (1948)

Polka Graph

Probably the most revelatory work included here are three works by Mary Ellen Bute, whose “Seeing Sound” animations date back to the mid-1930s—though the pieces included here are from the ’40s and early ’50s. Geometric shapes carefully synchronized to the mathematical structures of the accompanying (light classical) music and the inclusion of the skittering loops from an oscilloscope display make her films sound nerdish, yet they were distributed as pre-feature shorts for mainstream Hollywood movies—making her perhaps the most widely seen abstract animator of the era.

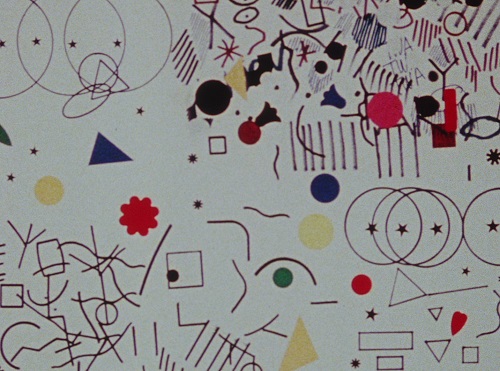

Jules Engel, Play-Pen (1986), (c) Center for Visual Music

A close contender would be Jules Engel, who contributed his talents to Walt Disney’s Fantasia (1940)—though not on the abstract sequence designed by his beleaguered colleague Fischinger. Engel’s design sense is openly enamored of high Modernists like Kandinsky, Calder and Miro, which is a good thing—especially in the phenomenal Play-Pen (1986) which transcends homage in its pulsing, frantic third act, which combine hand-drawn geometric loops with layered cascades of rapidly mutating symbols—colored squares, triangles and diamonds; Letraset flowers, stars, numbers and letters, all flashing stroboscopically then flipping to inverted colors. Rob Miller’s accomplished classical guitar soundtrack borders on the corny, but Engel’s musical choices are always interesting, so I probably wasn’t listening as carefully as I should.

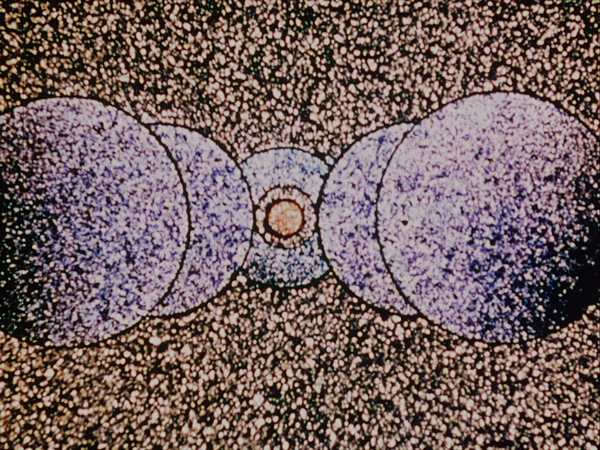

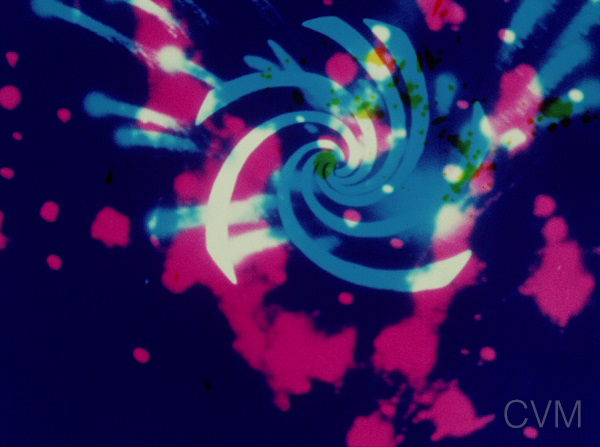

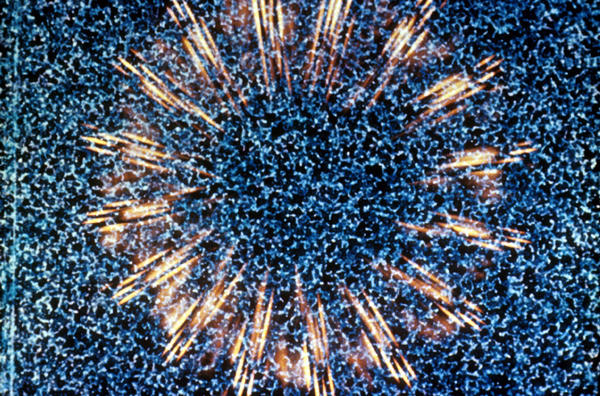

Jordan Belson, Chakra (1972)

Scoring was also one of Jordan Belson’s strong suits, dating to the late-’50s when he collaborated with Henry Jacobs on the legendary VORTEX light-and-sound collage happenings at the Morrison Planetarium in San Francisco. The three exercises in spiritual abstraction included here use gamelan, some kind of Tibetan singing bowl/gong dealie, and an original audio collage corresponding to the auditory phenomena associated with the awakening of each of the seven chakras.

This last is, unsurprisingly, the score for Chakra (1972), which purports to fulfill the same function visually—making the invisible spiritual realm visible in objective reality. This is an ambition that holds true for most of Belson’s richly psychedelic oeuvre, which he made with a closely guarded array of secret techniques involving real-time manipulations of light and material.

His glowing, throbbing color-saturated orbs, mandalas, cosmic clouds and showers of sparks are among the greatest works of 20th-century nonobjective art, but Belson withdrew increasingly from the mid-’70s on, removing his films from circulation. The CVM finally got his blessing to release five restored pieces on DVD in 2007—but with the three here, that constitutes less than a quarter of his output (not counting the 20,000 feet of unused effects he shot for The Right Stuff). An artist that is able to maintain their integrity and sincerity while producing such an exquisite and idiosyncratic body of work deserves much wider recognition. But it’s a start.

All images courtesy Center for Visual Music

For more info and to find Visual Music 1947–1986: www.centerforvisualmusic.org/visualmusicdvd