Since its inception in 2002 The Wende Museum’s corporate park location has had a discreet charm. The easy-to-miss suite is tucked behind a landscaped parking lot in a hive off Slauson in the former Fox Hills Mall— Culver City adjacent. Its charms unfold as you make your way up narrow carpeted stairs into the reception gallery, library and office and, on tour days, get ready for the guided journey to the vaults. Earnest and helpful staff will greet you and you can browse the small display rooms while you wait.

You may have encountered some of the Wende’s outdoor exhibits in the form of the largest piece of the Berlin Wall outside Germany that was installed across from LACMA (on the 20th anniversary of the fall of the wall in 2009). The Wende also sponsors salons and other Eastern Europe and Cold War-related cultural events like a time-warp Goethe institute, and makes its archives and artifacts available to scholars, artists and historians. The museum itself is worth a visit for an experience of a lovingly preserved slice of Cold War memorabilia and all it stirs up. You will have to hurry if you want to see it in its present location, however, as they are moving on up to a more glamorous space at the Culver City Armory to open sometime in 2014, which may just be worth waiting for.

The name Wende comes from the German for turn and refers to “die Wende” or the period just post fall of the Wall. The collection is heavy on the East German stuff, with a Stasi archive and the papers and books of the last German Democratic Republic leader, Eric Honecker.

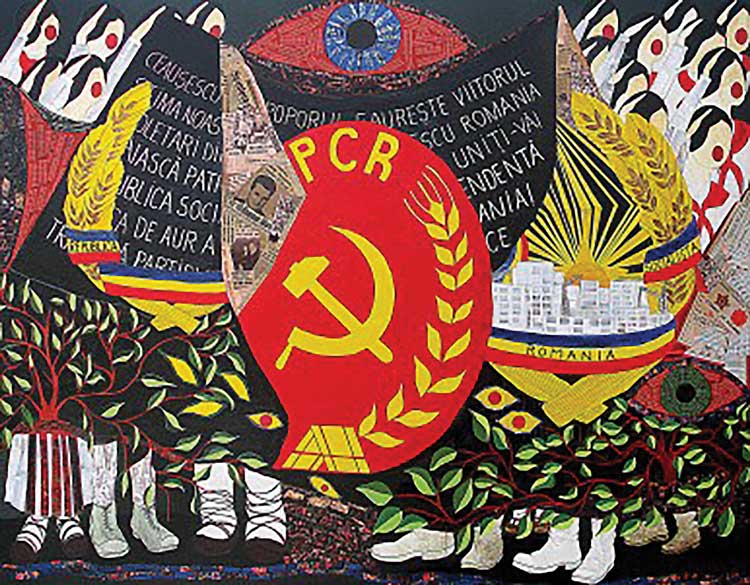

The visitor is presented with a capsule of the faded promise of a Socialist ideal once proposed by revolutionaries (and more crass versions provided by more motley leaders of the apparatus of state-run society) and may experience cynicism, a thrill of inspiration, or a catharsis of tragedy. The ardor and beauty in some of the art and design of the period resonates with any viewer who has responded to Socialist Realism, poster art and textile design from Eastern Europe, with or without an ironic squint.

Garden Egg Chair, 1968, Peter Ghyczy, Polyurethane frame, fabric

East Germany, Photo Credit: Marie Astrid González

The material can come across as fantastically camp (glowing faces of poultry farmers and glorious Electrification) and could lend itself to sloppy sociological pronouncements and an implied gloating over the West’s “victory” in the Cold War. In terms of art historical progress there is a weird timelessness to works in the style, whereby a 1951 painting of a Hero of Soviet Labor (by Al Sepodonikov), standing with grim pride before his well-plowed fields, has a more contemporary feel than the heroically-lit Steelworker by an Armenian (Gervasiya Vartanyan) from 1982, which could have been painted 50 years earlier. There seems still to be some revolutionary zeal in the design of 1960s consumer products like the Czech Tesla radio and the East German Egg Chair. I definitely look forward to seeing the full glory of some of the massive paintings and other boxed-up items in the collection, when the larger space opens.

One might identify with the American graduate student/founder, Justinian Jampol, based in East Berlin post reunification. He apparently became obsessed with collecting discarded bits of East German ephemera that people were getting rid of by dumpster loads, having been lured by the shinier products of the West. It’s a love labor reminiscent of the son in Goodbye Lenin who recreated a set of life in the GDR for his Communist mother, who was in a coma during the final days of the East Germany she had grown up serving. Jampol may also have been, like so many of us under the glaring lights of the marketplace, attracted by the more subtle hues that came out of Centralized Production. From the West, of course, the images from the Russian revolution to Polish theater posters, and all the knick-knacks of the forbidden East were anti-establishment, retro and recherché. He began an interesting and commendable project that is realized by the Wende Museum, with its collaborative spirit and involvement in ongoing historical investigation and art/cultural practice.

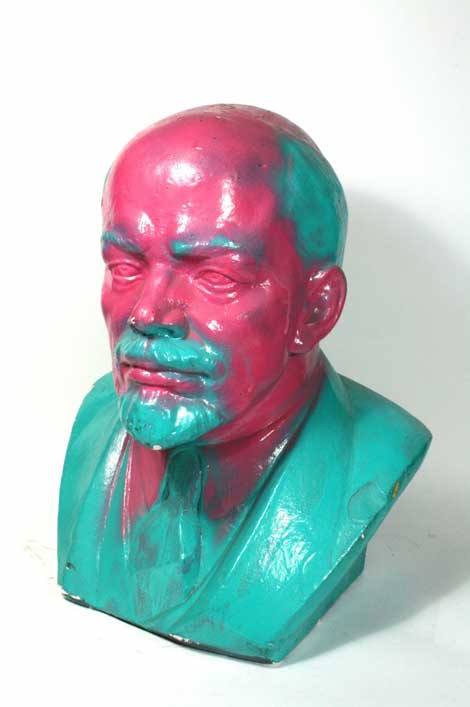

The museum’s stated mission is the promotion of discussion and understanding, and preservation a unique historical moment. Despite a scholarly and perhaps sentimental reverence for the works and the everyday experiences of people who lived, worked and produced in the Eastern Bloc, there is an unavoidable and unfortunate smugness which can come with our Far West perspective. The Russian term and concept of “poshlost” comes to mind, as defined by Nabokov and others to include not just material varieties of kitsch but also self-importance and falseness in its many forms. The knowledgeable volunteer guide, indicating the collection of busts of Marx and Stalin, noted casually “they’re pretty much the same thing.” Many might not so easily lump together philosophers and tyrants, and the question of curatorial slant is somewhat open. Alas, a measured scholarly response is not dictated.

Of course, one trouble with history is its collapsible narratives. In preserving representations of the Cold War, it is all too easy to slip into dead-tired rhetoric which would like to negate the Russian Revolution and conflate Stalinism and the post WWII Soviet sphere of influence with all things after 1917. One thing that was demonstrated by the grand Sochi Olympics opening ceremony (notwithstanding the silly onion dome balloons) was the proud display of revolutionary artists and an official reclaiming of once censored and exiled visionaries. Malevich and Rodchenko, and all the other Russian and East European, and American for that matter, avant-garde artists, writers and promoters of respect for labor and producers of wealth deserve better than to be lumped by NBC commentators into the “dark moments of Russian History” camp. And if it takes a dictator such as Putin to remind us of the power of art to promote truth and justice in the world, so be it. It can be used against him and the rest of the .01%, who roam amongst us.

Downstairs there is a display of Checkpoint Charlie and iron curtain fetish objects, demonstrating the militaristic repression suffered by citizens of Eastern Europe under Soviet influence. While one may celebrate freedoms, and never forget repression in its many forms, we might also guard against presumption to mark our higher status with historical distance. As we count our liberties, we might recall that it is precisely this type of arrogance that characterizes poshlost, and that we could do well to freely critique our own present culture and its artifacts, ideologies and creeds.

New location opens November 9, 2014 at 10808 Culver Blvd. at Coomes behind Vet’s Park, Culver City.

Images © 2014 The Wende Museum and Archive of the Cold War.