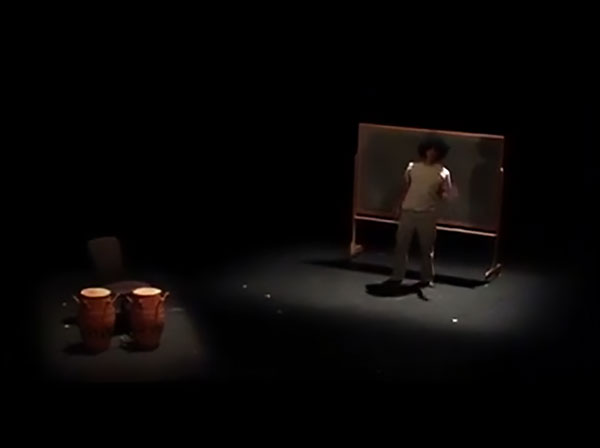

“I’ve been going the wrong way for a long time … it’s sort of a reverse commute.” This is said by Todd Gray at the start of his 2010 performance, Caliban in the Mirror. This seemingly autobiographical, storytelling piece has Gray on stage with a few props—a camera, a large afro wig, a blackboard, a drum set—verbally leading the audience through his discovery of the right way to go with his racialized self-regard. But the “reverse commute” is tricky. I think what he’s getting at is a critical way for his audience to understand his work and practice. Most people are typically based at home, and travel to a place of work. Instead Gray spends most of his time in the position, in the circumstances of work, and a crucial aspect of this work is figuring out how to get to a place that looks like home.

Todd Gray, Caliban in the Mirror, 2010

Performance (with Max King Cap) At REDCAT / Roy and Edna Disney/CalArts Theater, Los Angeles

In conversation with me for this profile, Gray cites editor and cultural theorist Stuart Hall as giving him the ability to understand that work will always be there for a black man in western culture, because, as he explains to me, the dominant culture is always trying to define you, even if you are skilled at defining yourself. Gray says the lie is that we are fixed subjects or subjects that are this or that, articulated through a binary opposition. Stuart Hall taught him to resist, by being constantly on the move defining and redefining the self. The theory term for this is “problematize,” which until this conversation with Todd Gray has always sounded rather woolly to me. Now it sounds like a navigation strategy.

Gray is very clear about saying he sees himself as a public activist whose primary work is examining blackness. The series of works he has produced over the years are evidence of this relentless focus. “Urban Myths” (1983–87) consists of photographic images of naked, dark-skinned bodies with charcoal drawings of ancient masks and hand-written script placed on the images—mythologizing them, raising these bodies to the status of emblem. The “Afrotronic” series (2008–12) is made up of heavily pigmented prints that essentially refract the viewer’s sight of trees, plant life, and native inhabitants of Ghana, creating a poignant—but also compounded and composite—view of one of the places he has made a residence. Born in Los Angeles, Gray came to decide to put down stakes in Ghana after first traveling there in 1992 with Stevie Wonder to shoot an album cover and music video. Wonder told him that the country included some main exit ports for the slave trade, essentially saying that Ghana was where many African Americans originated. That thought percolated for some time. When Gray returned to Ghana 13 years later for an art show, he decided to build a studio and home there with his wife Kyungmi Shin.

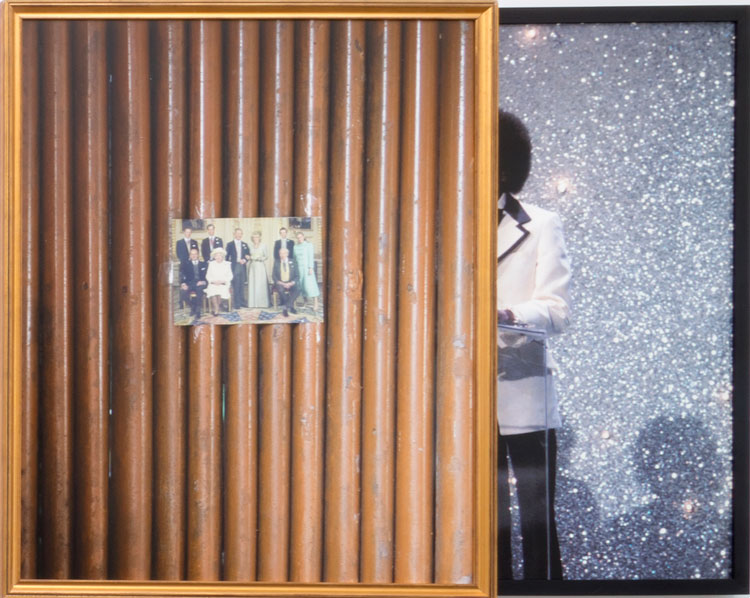

Todd Gray, Mirror, Mirror, 2014.

As Gray has moved through distinct conjugations of black and male identity, he is also consistently redefining his primary medium, the photograph. This concern with redetermining what photographs can be and do is apparent in “Urban Myths” and “Afrotronic,” but also in “California Missions” (2004–06) a series of taxidermic sculptures of animals whose bodies are physically intersected by printed photographic images. Here, in the body of work most concerned with the philosophical ramifications of images’ simultaneous representation and mediation of material existence, the photograph’s relation to the things it represents is dramatically changed. Animals are certainly reflected by the photograph and recontextualized by it, but also bisected by the image, and swallowed up in it.

Todd Gray, Takoradi Face, 2014

His latest body of work, “Exquisite Terribleness,” (2013–16) is for me his most ambitious and most successful. This series of photo-based installation pieces looks to redetermine both medium and man, and does so by using haunting, surrealist imagery that makes the inherent complexity of the diasporic subject not something to be avoided or tolerated, but examined and celebrated.

This body of work constitutes the fourth time Gray has instrumentalized the archive he created while being employed as Michael Jackson’s official photographer in the early ’80s. The first time he did so he was led there by his MFA professor at CalArts, Alan Sekula, who convinced Gray that this archive was a rich trove for important work. Sekula also got Gray reading bell hooks, Henry “Skip” Gates, W.E.B Dubois and Frantz Fanon. According to Gray, their collective tutelage brought him to the inescapable conclusion that, in his words, “I suffer from mental colonialism; my consciousness has been hijacked.” I understand through conversation with him that the time he spent as Jackson’s photographer, beyond providing an image cache, also made him fear the consequences of being defined by the dominant culture.

Todd Gray, Gang Star, 2016

Michael Jackson was literally a super-star, a black, ethnicized, performing male body that came as close as possible in late-20th-century America to transcending the heavily policed boundaries of blackness and masculinity. At one point it seemed that Jackson moved through those barriers with such ease that he essentially transcended them, purchasing a new body and new family as he flew. But he didn’t. As Gray says, “Michael was born black and died white.” So keep moving. Hired to help construct and maintain the marketed image of Jackson increasingly muddled with the myth, Gray must have seen and understood that the pop star didn’t transcend race or subvert it; Jackson actually made its privations more visible and palpable by providing a stark contrast to how other black men were perceived and treated by the same people who bought his records, collected his memorabilia and fainted at the sight of him.

By the time Gray had started work on “Exquisite Terribleness,” he had figured out that the work he had done around Jackson was really work about himself. This series is also about the collective category of blackness and entails a vision of that which is radiantly hopeful. The series is visually and intellectually powerful work. It consists of photo portraits of black people whose faces are obscured by overlapping nested photos that are placed in frames found in garage sales and Goodwill stores. For example, Gang Star (2016), features a portrait in heavily tinted blue of a man wearing a plaid shirt throwing what we might assume to be “gang signs.” His face is covered by a circular photograph of stars against a black sky (images from the Hubble telescope), overlapped by another circular photo of a black man with his back to the camera. The man is wearing all white, standing in a boat in an idyllic island setting, perhaps using the oar in his hand to row towards shore. Gray says that the work is “an attempt to reframe how we imagine ourselves, or I imagine myself, as a diasporic subject in western culture.” It is clear that blackness in the diasporic experience, in his view, is layered, discordant, inflected by pop culture, and obeisant to its celebrities.

And yet, there is that shore in sight.

All images © The Artist, 2016. Courtesy of the artist and Meliksetian | Briggs, Los Angeles.

See Todd Gray’s work in the upcoming Los Angeles biennial, “Made in L.A.” opening June 12, at the Hammer Museum.