Mining one’s own archive—especially if you are Michael Jackson’s personal photographer—can become a fruitful catalyst for exploration. Todd Gray’s recent works, framed photographs that are collaged together to become in essence bas-relief sculptures, juxtapose images from his archive of Michael Jackson photographs with landscapes and portraits taken in Ghana, where he has a studio, and in Italy, where he recently completed an artist’s residency. While these evocative photo-sculpture hybrids touch on issues of race, class and gender, they are in many ways self-portraits in which Gray represents the different aspects of his life as framed fragments. He creates new narratives through the careful layering of what others might consider unrelated material.

While a starting point for many of Gray’s works are his images of Michael Jackson from the 1970s and 1980s, it is also significant that many of these images are presented in found frames—imperfect and battered throw-aways that Gray picks up along the streets of South Los Angeles. Implied in his works is a mingling of cultures, locations and time periods that are central to both Gray’s personal history and his subjectivity with respect to the African diaspora and the larger subjects of race, gender and class.

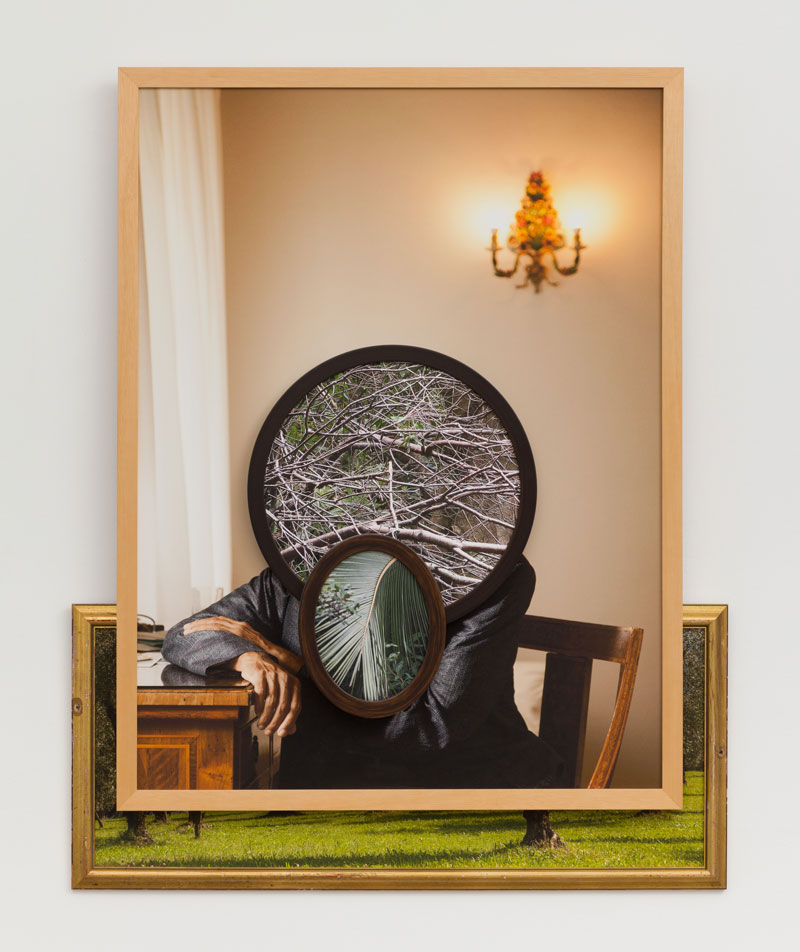

Todd Gray, Manil, 2018, Four archival pigment prints in artist’s frames and found frames with UV laminate

The two photographs in Flora Africanus (D.C.) (all works 2018) are encased in gold-toned wooden frames in differing states of disrepair. The rectangular background image is a black-and-white picture of a cheering crowd, presumably shot from the stage during a Michael Jackson concert in Washington, D.C. It is overlaid with an oval shaped color image of exposed tree roots extending down from the trunk like sinewy tentacles. This image within an image is offset toward the top covering most, but not all, of the crowd. While the outstretched arms and hands of the audience visually connect with the criss-crossed network of tree roots, Gray’s juxtaposition further imbues the image with double meaning: what and where are one’s roots?

In Gray’s work, gestures are isolated and presented out of context, people are disembodied, their images covered by framed fragments from the natural world. Maya Venus includes a landscape turned on its side, the hour-glass shape of a forest surrounded by sky and its reflection in a river. This shape parallels the form of the body it masks in the color image below: a close frontal portrait of a black man at the beach. The man’s forehead, eyes and nose have been covered by a circular black-and-white photograph that isolates two clasped hands. Gray’s montages are purposely ambiguous. His faceless portraits and fragmented landscapes speak to mingled identities and what is left out of history. The way these disparate photographs intersect and the narratives that can be inferred or intuited by reading across the various subjects invites viewers to engage with the work. These complex and seductive pictures are challenging puzzles; each represents a point within Gray’s oeuvre and explores notions of a public persona. Additionally, they function as formal investigations that traverse time and memory.