Always following his impulses, Timothy Washington is an artist’s artist, and in the Southern California African-American artist’s community is one of the last remaining practitioners from South Central LA’s Golden Age of Assemblage (late 1960s to mid-’70s). Washington somehow slipped below the radar, but with the genre enjoying a comeback, his first Los Angeles solo museum exhibit showcases numerous pieces created over the past several years that are now being revisited and critically examined.

Mix one part Sun Ra, one part Thelonious Monk and one part Noah Purifoy, and you have Washington’s concoction of visual gumbo. He celebrates and elevates the everyday, inserting “end time” sub-texts that espouse his brand of street corner prophecy and spirituality. Due to the overabundance and oversaturation of objects flooding Washington’s surfaces, his sculpture’s surfaces emanate visual shouts, exemplified in the three-part series Energy Source (2003), Second Warning and Final Notice (latter works 2003–13).

In Introductory Tale (1967) the viewer confronts a more than life-size sculpture of a man with outstretched arms, broken chains at his feet, with a flip-down compartment coming out of his back containing a Bible turned to The Book of Exodus, which doubles as a liberation text. It shares a thematic and formal affinity with Ron Griffin’s Screaming Man (c. 1970).

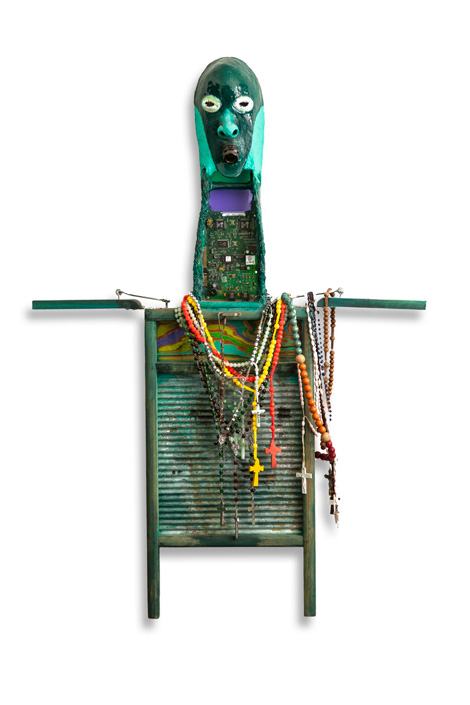

Nine of Washington’s early aluminum drawings or “drypoint improvisations,” coated with scratched away auto primer, were borrowed from the artist’s collection and private collectors, looking every bit as fresh now as they were when they were first produced 45 years ago. The treatment of the round silver eyes are a throwback to the masks found among the Dan Ngere tribe of the Ivory Coast, suggesting an altered state, which is revisited in his “Washboard Series” work Old and New (2012).

The artist explores a number of polarities, dualities and opposites in such works as Negative vs. Positive (1998) and Black Cross and White Cross (1993). Employing all manner of recyclable elements in his work the artist moves around information-energy units using a combination of cotton balls and glue, like brick and mortar. His assemblages and wall reliefs are as meticulously conceived as they are intensive and ambitious. It reminds the viewer of James Hampton’s laborious tinfoil alter piece, The Throne of the Third Heaven Nations Millennium General Assembly (c.1950-64), collected by The Smithsonian.

Washington’s “Spoon Series” and “Washboard Series” set up a call-and-response, or social and cultural interface, in homage to the blues aesthetic and its practitioners. An orchestra of 21 spoons and five washboards fill the space with all the confidence of Muddy Waters, holding court in performance. This modality carries with it the human element where the spoons and washboards operate as extensions of the human body and share dual histories as both functional objects and musical instruments, transposing potential energy into kinetic energy, or light into sound.

Within certain circles, it is agreed that we live in an energetic universe, and the highest creation is love. Washington shares his love as a creative medium and energy shifter, offering the visitor a rare opportunity to see the artist’s ancient-futuristic universe.