It’s been a tumultuous week in Los Angeles; and for a change, we can’t blame it entirely on the Putin-wannabe currently installed in The White House or his cronies and GOP enablers – notwithstanding the fact that he happened to blow into town this same week to pick a few pockets. As usual he was upstaged, which probably infuriates him; but then it’s not hard to upstage a would-be strongman who physically resembles a sack of cotton candy.

Straight off, we had the drama of a very public dismissal of a very popular public intellectual – and that is what distinguishes the dismissal of MoCA’s now-former Chief Curator Helen Molesworth from otherwise comparable dismissals. (In some ways this was the week of the public intellectual here in L.A.) News is beginning to filter out that complicates the initial view of MoCA director Philippe Vergne coming to a stand-off with his Chief Curator over conflicting curatorial agendas. In fact, the actuality may resonate pretty well with a chord of disillusioned sadness I was sounding still earlier in the week (well, around the time the Met announced James Levine would never be coming back to that locus of so many ecstatic moments at Lincoln Center – something particularly heartbreaking about that particular fall from grace). Should we be grateful this didn’t have much to do with sex? Or (apparently) gender?

Or did it? Another frustration here is that we really can’t get the complete story until we hear from Philippe and Helen both. Coming on the heels of the recent dust-up over MoCA’s recently canceled fund-raising gala after its designated guest-of-honor (Mark Grotjahn) bowed out (frustrating that many of us could have seen that one coming, but the MoCA powers-that-be (we have to assume that included several influential board members) embarked on their plan regardless), the timing was inauspicious to say the least. But what was most disheartening was that we – meaning the larger community of L.A. artists and the audience and commentariat who observe them and their work, who follow their careers, write and report on them and the cultural establishment that may or may not make room for them – felt we were losing a critical voice in this community and beyond that, the global art community.

Or did it? Another frustration here is that we really can’t get the complete story until we hear from Philippe and Helen both. Coming on the heels of the recent dust-up over MoCA’s recently canceled fund-raising gala after its designated guest-of-honor (Mark Grotjahn) bowed out (frustrating that many of us could have seen that one coming, but the MoCA powers-that-be (we have to assume that included several influential board members) embarked on their plan regardless), the timing was inauspicious to say the least. But what was most disheartening was that we – meaning the larger community of L.A. artists and the audience and commentariat who observe them and their work, who follow their careers, write and report on them and the cultural establishment that may or may not make room for them – felt we were losing a critical voice in this community and beyond that, the global art community.

There are many talented curators in Los Angeles; and there may be a number of curators scattered across the planet who can fill the top curatorial position at MoCA. But – as Philippe Vergne already knows – s/he won’t be Helen Molesworth. Molesworth has a singular voice and a singular vision; and in the three short years she’s been with the Museum, she’s managed to re-frame and recontextualize a large part of the conversation around contemporary art. Whether or not this was something radical or unexpected in L.A. is not really the point; and to some extent, her work here is neatly positioned on the same continuum of curatorial work she’s been doing since she was a curator at the Wexner Center in Columbus, Ohio. In some ways, her collaboration on the Black Mountain College show, Leap Before You Look gave us something of a preview as to how she might approach the programming of L.A.’s artists’ museum, and the conversation she wanted to build around it. In large part, this was a conversation that had already begun (I take some satisfaction that the magazine whose website this blog happens to occupy has had some hand in this). But Molesworth’s brilliant voice and committed and informed viewpoint gave it shape and cogency.

It’s been many years since most of us parked our copies of Greenberg and Alfred Barr’s old MoMA catalogues in the most inaccessible places in our bookcases; but it was Molesworth who effectively manifested a heterodox post-patriarchal (post-parochial really) cultural narrative with her fresh and invigorated re-installation of MoCA’s permanent collection. I loved that she wasn’t reticent about pushing a juxtaposition or configuration that might be viewed as idiosyncratic or slightly tendentious. (I’m thinking of a juxtaposition like Arshile Gorky and Alina Szapocznikow; there were others.) I’m sure there were any number of visitors, who might have had second – and successive – thoughts about one installation or another. And that was half the point – it’s so fresh, alive, now.

Then there was the Kerry James Marshall retrospective – a show that had an air of inevitability about it. But inevitable when exactly? It was Helen Molesworth who made the case for now – almost literally – turning the evidence to every angle of illumination and reflection, with precise observation, airtight logic, perspective, insight, great wit, more than a dash of humor, and elegance. Marshall’s painting is a very rhetorical art and Molesworth distilled every facet of it into an argument as seamless as a silken staircase. At the press preview, she delivered what was essentially a fully composed lecture as we moved through the show without a single note, as if she were improvising it on the spot (which I suppose is also possible). We looked where she told us to look and looked some more, laughed, and hung on every word. (I was ecstatic by the time she wrapped it up.)

But people are complicated. Sex is hugely complicating, whether we like to admit it or not. (Although that doesn’t appear to have been an issue in this instance.) Publicly charming people can be perfectly monstrous in certain circumstances (not even necessarily behind closed doors). Stardom goes to people’s heads. Limits are breached now, again, repeatedly; and before long they no longer exist. The cliché holds a kernel of truth: power can corrupt. Sufficiently empowered and enabled, perfectly intelligent people are capable of wreaking havoc in any number of different situations public and private. Every Body Wants to Rule the World. And perfectly intelligent people make mistakes, even stupid mistakes – it just happens. (Which is why we have to hear and heed the supporting players, the concerned neighbors, the advisors.) And no – this is not an argument for AI.

What’s sad is that it’s probably too late to salvage; when at some point – a year, two years ago – the concerned players might have taken a moment (or more) to sit down to coolly, comfortably discuss the situation and how to resolve or work around it. (I’m thinking that this may be where money/funding/budgets also comes into play. Okay there’s that – but the trustees should just pony it up.) It should go without saying, but – people need to listen.

I’m trying to be okay with this – even though it’s been a difficult week with so many venerable heads on the block. The good news is that Helen Molesworth is not going away – she’s going to continue curating, writing, and lecturing, and generally being the fabulous public intellectual she’s been for some time. Better to eat the world than to rule it. (At least that’s what I think Susan Sontag might have said.)

So on Wednesday evening, I went to the second in the Broad’s series of Cross-Hatched concert events organized in conjunction with the Jasper Johns exhibition I wrote about (at some length as you may recall) in my last post. This concert, like the last, was inspired by John Cage – who, along with Merce Cunningham, was a very close friend of Johns – and also, by one of the best of his ‘cross-hatching’ works, Usuyuki, which in turn was inspired by time Johns spent in Japan. (‘Usuyuki’ means ‘light snow.’) The featured pianist was Adam Tendler, and he was remarkably versatile; really much more than simply a pianist, though that would have been more than sufficient – he was superb. In addition to the music – which in its miniature, frequently quasi-pentatonic encapsulations managed to trace an entire musical evolutionary line, from Debussy and Ravel through Satie, to the work of Cage and others – it was a performance of gesture, movement, small actions, noise, and random events (how random we only really found out after the performance was finished).

The performance was held in the foyer/lobby of the museum, less elegant than the Oculus room (which may be one of the most elegant salon-like spaces in the city), but more spacious and more expansive generally. It was particularly appropriate to this recital in that it brought the music and movement performed within the space in contact with the exterior (an extension of the natural worlds conjured by the music) – a built environment, and dark; but lit by streetlights, light spilling from the museum (and adjacent structures), and vehicle headlights. The tall glass windows seemed to rotate against the concrete walls as the lights of large vehicles moved down Grand Avenue. Cage(d) in a kaleidoscope.

Praying for rain on this cool night (which came!), it was sublime to listen to Tendler perform Cage’s Haiku (I through V, plus an unnumbered one and a second version of Haiku I), which were like bagatelles, not necessarily minimalist, wrought out of exactly the sort of fleeting natural event that inspired Usuyuki. Tendler paid due reverence in turn to the sun with Toru Takemitsu’s Corona (1962) (a five-movement work that begins with a ‘study’ for “Vibration” and closes with “Conversation”). There was also music by Toshi Ichiyanagi. Although there was music for prepared piano (Electronic Music for Piano, 1964 – truly fascinating) my companion and I vaguely hoped that there might be music for both the piano and a toy piano – which was there and quite visible. There wasn’t; but the toy piano was featured in one of the Fluxus performance pieces Tendler performed before closing with his last two Cage pieces (the last of which was accompanied by video of Merce Cunningham’s Second Hand, which was screened on the Broad’s concrete walls). For Dragging Suite (by Nam June Paik),Tendler actually dragged the piano, with several dolls clinging to its legs, all the way out to the glass walls of the foyer. (I took a moment to regress to age 3, and took to those toy keys myself – a moment that was recorded for Instagram.)

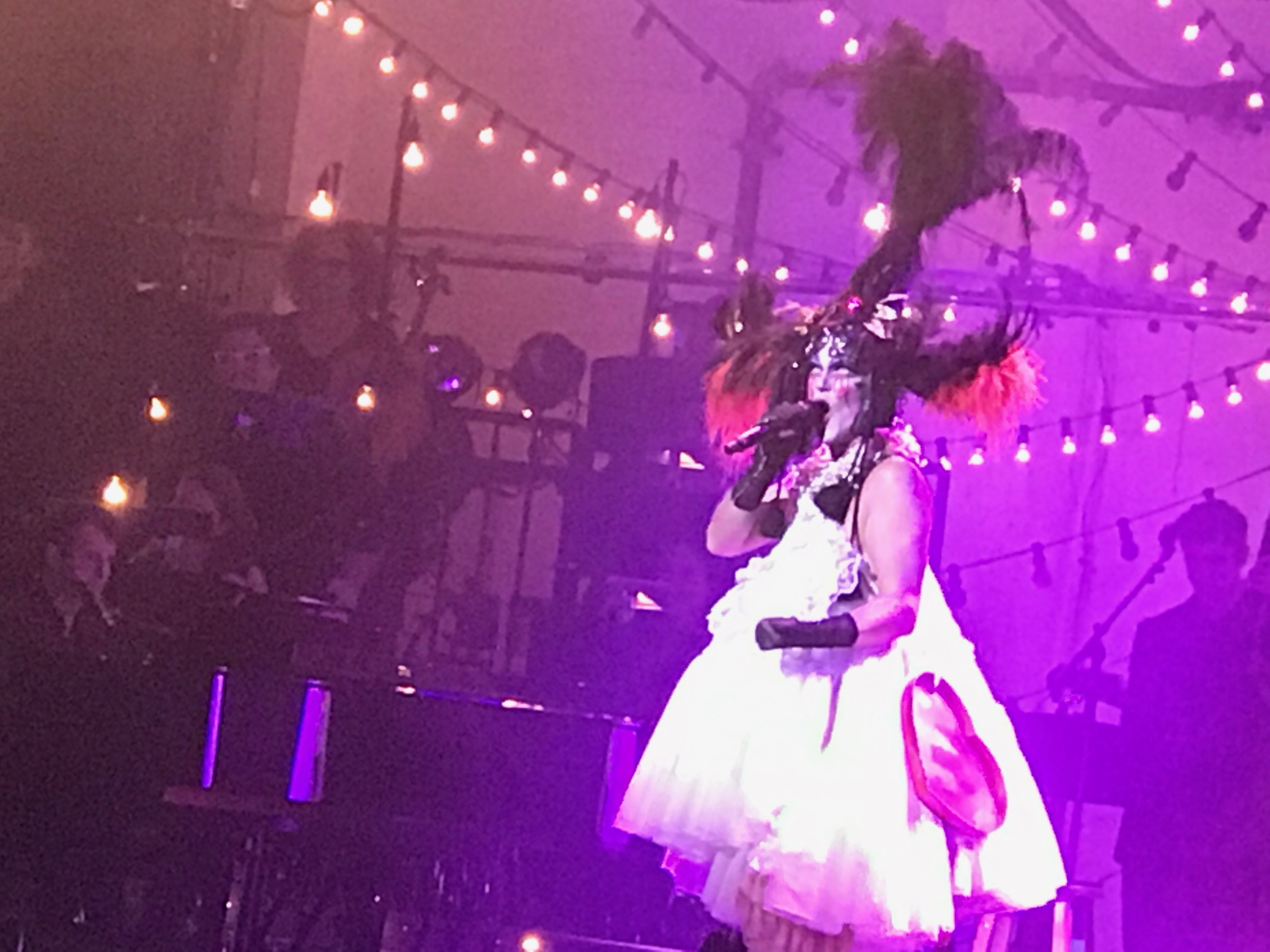

What comes down must go up – isn’t that how it’s supposed to work? I’m talking about public intellectuals again – and make no mistake about it, Taylor Mac is a public intellectual (which may actually be his only flaw as a performer – but what a performer!) On Thursday evening, I was privileged to witness the apotheosis of this Exterminating Angel of America. (And yes – it was a bit like that, since this was a party you weren’t going to be leaving for quite a while.)

There’s a certain kind of performance art I’ve occasionally characterized as failed theatre or failed theatrical revue. A 24-Decade History of Popular Music is nothing remotely like that – for starters simply because it’s pretty spectacular theatre. But – and it’s Taylor Mac who actually raises this question – is it theatre? Straight answer: yes, of course – but it’s a very special kind of theatre; and also a whole lot more. In a way, to get some perspective on it, you really have to go back to drag cabaret. (Yes, there was once such a thing; and there probably still is.) Or maybe just cabaret. Oh and yes, I mean that Cabaret, too. (And judy is very open about that level of ambition – or at least judy was on Thursday evening.) It’s a world evoked cinematically by filmmakers like Billy Wilder and Bob Fosse (Taylor Mac’s stage persona is practically a fusion of Shirley MacLaine’s Charity Hope Valentine and Marlene Dietrich’s Erika von Schlütto. The cabaret element has to do with the audience. This is far more theatrical than cabaret – really it’s a species of theatrical follies, if the Folies Bergères could be pitched to a level of grandeur beyond the most grandiose imagining – with the merest dash of psychedelic queer funk by way of legendary troupes like the Cockettes and the Angels of Light. But even from a big stage a few hundred yards away, Taylor Mac works the audience as if s/he were Marlene/Erika among the American soldiers and black marketeer Berliners at the Lorelei (and how gay is that?). It didn’t take more than a couple of songs before s/he had the entire audience in the palm of judy’s hand (quite a feat, given everything judy and judy’s ‘dandy minions’ were occupied with up there – the costume changes and adjustments alone are pretty miraculous). It didn’t hurt that Mac had a fantastic band – really a small orchestra – backing him up, under the direction of Matt Ray. I’m not sure Ray is quite the pianist Friedrich Hollander was for Marlene, but he’ll do – and he’s also a genius arranger – a critical factor in the delivery of this sometimes arcane material.

There’s a certain kind of performance art I’ve occasionally characterized as failed theatre or failed theatrical revue. A 24-Decade History of Popular Music is nothing remotely like that – for starters simply because it’s pretty spectacular theatre. But – and it’s Taylor Mac who actually raises this question – is it theatre? Straight answer: yes, of course – but it’s a very special kind of theatre; and also a whole lot more. In a way, to get some perspective on it, you really have to go back to drag cabaret. (Yes, there was once such a thing; and there probably still is.) Or maybe just cabaret. Oh and yes, I mean that Cabaret, too. (And judy is very open about that level of ambition – or at least judy was on Thursday evening.) It’s a world evoked cinematically by filmmakers like Billy Wilder and Bob Fosse (Taylor Mac’s stage persona is practically a fusion of Shirley MacLaine’s Charity Hope Valentine and Marlene Dietrich’s Erika von Schlütto. The cabaret element has to do with the audience. This is far more theatrical than cabaret – really it’s a species of theatrical follies, if the Folies Bergères could be pitched to a level of grandeur beyond the most grandiose imagining – with the merest dash of psychedelic queer funk by way of legendary troupes like the Cockettes and the Angels of Light. But even from a big stage a few hundred yards away, Taylor Mac works the audience as if s/he were Marlene/Erika among the American soldiers and black marketeer Berliners at the Lorelei (and how gay is that?). It didn’t take more than a couple of songs before s/he had the entire audience in the palm of judy’s hand (quite a feat, given everything judy and judy’s ‘dandy minions’ were occupied with up there – the costume changes and adjustments alone are pretty miraculous). It didn’t hurt that Mac had a fantastic band – really a small orchestra – backing him up, under the direction of Matt Ray. I’m not sure Ray is quite the pianist Friedrich Hollander was for Marlene, but he’ll do – and he’s also a genius arranger – a critical factor in the delivery of this sometimes arcane material.

That description obviously would not include standard hymns like “Amazing Grace,” – or for that matter, “Yankee Doodle Dandy,” for which Mac was essentially using his own body as the reference point. But bringing allegorical material like “The Apple Tree” (if that was actually the song’s title) to musical and theatrical life was something of a trick; yet Mac, his musicians and minions managed to get that tree up and in bloom and to place a colonial/revolutionary ‘Adam’ and ‘Eve’ beneath boughs – or the umbrella of Mac’s Machine Dazzle engineered headdress, whichever offered more shade. It was at this point that we made ourselves comfortable with the audience-participation aspect of the program, as the dandy minions distributed actual edible apples to the audience – fully intended for consumption; and I soon found myself biting into that apple handed to me in the dark. If I had my doubts about making it through a six hour theatrical performance, they began to dissolve here (though I was compelled to return to the lobby some minutes afterward to dispose of my apple core). There were several other points, when an opaque window-shaped screen descended for a costume change that also offered opportune moments to take care of business, theatrical or personal.

Apples naturally gave way to hard cider – drinking songs – as Mac noted that finding fresh unpolluted drinking water was not always a straightforward proposition, which encouraged the colonists to turn to alcoholic libations, which in turn would eventually lead to movements both religious sectarian and political to discourage public drinking (or at least drunkenness) or prohibit it altogether. The drinking songs were scarcely underway when a sea of bonnetted women (and probably a few men) – a full temperance choir – stormed the stage, where Mac welcomed them. And this is where I began to see sparks of genius. Enter the chorus – or choruses, plural; enter the gadflies; enter (and exit) the villains – but actually Mac would handle that all by himself, because s/he would sing us the villains – not exactly acting them out – not when s/he’s Lady Liberty or the Lady Eve, Ma Kettle or Dolly Levi – but drawing the audience’s attention to their looming shadows. I was about to say ‘hanging’ shadows – and those dark spirits may be there, too. To take it beyond a theatrical revue, you have to have a contending force – or two, or twenty. Of course audience participation would not only be encouraged, but required. (I usually find these exhortations highly resistible; but you would have seen me munching on my apple, leaning on my neighbor in the next seat over, waving my arm in the air, and rowing away in my imaginary canoe.) Not to discount the stage, which I thought was perfect in its transparently imperfect way – but Mac must have the entire theatre as judy’s stage – orchestra, balcony, and aisles. (And as long as Mac is contemplating Hollywood, let’s just make it one big soundstage. Put the second unit in the balcony.)

Apples naturally gave way to hard cider – drinking songs – as Mac noted that finding fresh unpolluted drinking water was not always a straightforward proposition, which encouraged the colonists to turn to alcoholic libations, which in turn would eventually lead to movements both religious sectarian and political to discourage public drinking (or at least drunkenness) or prohibit it altogether. The drinking songs were scarcely underway when a sea of bonnetted women (and probably a few men) – a full temperance choir – stormed the stage, where Mac welcomed them. And this is where I began to see sparks of genius. Enter the chorus – or choruses, plural; enter the gadflies; enter (and exit) the villains – but actually Mac would handle that all by himself, because s/he would sing us the villains – not exactly acting them out – not when s/he’s Lady Liberty or the Lady Eve, Ma Kettle or Dolly Levi – but drawing the audience’s attention to their looming shadows. I was about to say ‘hanging’ shadows – and those dark spirits may be there, too. To take it beyond a theatrical revue, you have to have a contending force – or two, or twenty. Of course audience participation would not only be encouraged, but required. (I usually find these exhortations highly resistible; but you would have seen me munching on my apple, leaning on my neighbor in the next seat over, waving my arm in the air, and rowing away in my imaginary canoe.) Not to discount the stage, which I thought was perfect in its transparently imperfect way – but Mac must have the entire theatre as judy’s stage – orchestra, balcony, and aisles. (And as long as Mac is contemplating Hollywood, let’s just make it one big soundstage. Put the second unit in the balcony.)

The other way of looking at it is (again revisiting drag cabaret – or simply ‘diva’ cabaret along the lines of Marlene’s “Lorelei”) the notion of working a theatre as if it were a club or cabaret. This has also been done – at least in reverse. Consider the christening of the Roxy in West Hollywood – by way of The Rocky Horror Show (before it actually hit the big screen), with that ‘sweet transvestite’ “from traaaaaannnnnnnnn – sexual – Transylvani-AAAAAHHHHAAAAAA” officiating. Tim Curry actually entered from the back of the house, making his way through the center of the club to the stage, depositing clouds of glitter with every step he took (our hands practically touched as he passed my table). The idea really isn’t so far off – the American – I mean Transylvanian (transsexual?) – dream; the homecoming (or more precisely, the home we can never return to, the home no longer there, that can never be the same).

Or the home we wouldn’t recognize – then or now—because it represented a part of America we might not have a clue about – the America(s) forever scarred by slavery, exploitation, violence, poverty and ignorance. As Mac crescendoed a kind of sea chantey to a rousing close, with half the audience joining him in spirit to raise a ship’s sails and take to a seaport’s streets in search of – well, no – as it turned out, not exactly just any girl in any port, Mac called an abrupt halt to the applause that had just begun, and quickly filled in the backdrop – that the girl the sailors would have been seeking out would have been black, would in fact have been a slave, and so entirely vulnerable and helpless to fend them off, whether singly or in a gang-rape. The ultimate, horrifying implications of such an incident were immediately clear, and the audience momentarily hushed. Such material might also be considered “community-building,” Mac explained in a concise American history re-write – just ‘not the communities we might have in mind’; and the dark reality of the ‘sundown town’ suddenly loomed before us.

Half a century or so ago, the political economist, Harry Magdoff, introduced me and most of my peers to the way British-turned-American colonialism during the 17th through 19th centuries paved the way for American imperialism in the 20th. We were getting a similar education here – with a kind of Foucault-by-way-of-Deleuze gloss (and maybe some third-wave feminists, too): that the “hetero-normative” attitudes that played out across the culture might have political implications, and that colonialism and its subsidiary practices of exploitation – political, cultural, economic, personal and sexual – might not only represent an unforeseen consequence, but actually be mutually reinforcing.

I confess I was one of the people who ‘cheated’ and lifted my black sleeping mask. There was no way I was going to take my eyes off this dazzling performer for almost an hour. But I have to say those who kept them on were well stimulated – with flowers, bits of fruit (mostly grapes) and the audience members in the seats around them. Mac threatened to “shame” us if we cheated; but as he also frequently reminded us throughout the show, “we can do this because we call it performance art.” He hardly needed to repeat himself – and in any case, I’m not even sure I agree. He could “do this” because it worked theatrically. For myself, as a de facto participant in the festivities, I felt similarly permitted.

And so the week of the public intellectual reached its glorious climax – ably assisted by genius designer, Machine Dazzle (the costumes are themselves a kind of conceptual art), and Mac’s terrific stage orchestra. The second half of Mac’s 24-decade History continues this evening, with the 20th and 21st century finale Saturday night; and if I haven’t made it clear already – Surrender Dorothies! to the anticipated six-hour captivity. You’re free to come and go regardless – but mostly you’ll be staying. It’s (Living) theatre, follies, club or cabaret, and ‘late night double-feature picture show’ – but what it ends up feeling like is one of the best parties that’s ever held you willingly captive.