The “death of painting” is frequently traced to the work and writing of Donald Judd. In 1965’s “Specific Objects,” the same essay in which Judd outlined painting’s limitations—above all, its inherent illusionism—he even more forcefully predicted the death of sculpture. Describing sculpture at the time as a “set form” or “a certain kind of form,” he wrote, “it can probably be only what it is now—which means that if it changes a great deal it will be something else, so it’s finished.” He adamantly maintained that his own works, and those by such fellow artists as Dan Flavin, Robert Rauschenberg and Claes Oldenburg, were not sculptures but objects. Shortly after Judd’s article was published, critic Lucy R. Lippard organized the exhibition “Eccentric Abstraction,” which included, among others, Eva Hesse, Louise Bourgeois and Bruce Nauman. Her catalog text emphasized the “nonsculptural” quality of their three-dimensional objects, describing conventional sculpture as an “apparent dead end.” None of this is to suggest that traditional sculpture wasn’t still being made by Anthony Caro, Mark di Suvero and many others. It is to say that the sculptural idiom, as old as art itself, was exhausted and obsolete.

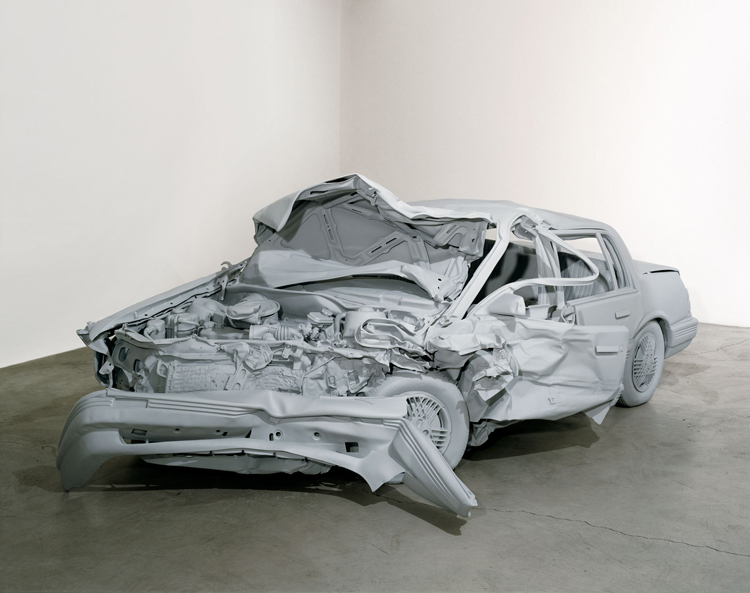

Donald Judd, Untitled (Stack), 1967, lacquer on galvanized iron, 12 units, each 9 x 40 x 31″, The Museum of Modern Art, NY, ©Judd Foundation, licensed by VAGA, New York.

Historical as well as modern theories of sculpture, much more than those of painting, emphasize its materiality: how and from what it is made. The Latin verb sculpere means, in fact, “to carve.” In an unpublished interview with Prudence Carlson, Judd said, “I don’t like to use the word sculpture because it’s carving to me.” The subtractive process of carving was later supplemented by the additive process of modeling (made permanent in bronze casts) and for centuries these two techniques defined the art of sculpture. With Picasso’s invention of construction in 1912, which was augmented by his appropriation of industrial welding in 1928, sculpture’s vocabulary was greatly expanded. The problem, as Judd often pointed out, is that construction (and assemblage) are by nature compositional and based on the juxtaposition of multiple parts. Whether carved, modeled, or constructed, sculptural compositions, unlike singular, whole objects, are arranged according to the sculptor’s sense of balance, individual style, or personal expression.

Another defining convention of sculpture is its subject matter, which was, with rare exceptions, the human figure. Most abstract sculpture retained a more or less obvious anthropomorphism that Judd associated with “statues” (the Latin word for sculpture is statuaria). As Robert Morris, Judd’s minimalist colleague, wrote in 1969, sculpture “was terminally diseased with figurative allusions . . . . Sculpture stopped dead and objects began.” The Russian constructivists were among the few modern sculptors to produce wholly nonreferential forms; others like Malevich and Vantongerloo ended up with architectural, in place of human, references. On purely abstract terms, most sculpture was unable to compete with painting and therefore rendered only conditionally modern. Characteristic of sculpture is its material existence as—if not a substitute person—a thing, and potentially some-thing, in the world. Because it was man-made with industrial materials and techniques, minimal art was often compared to furniture. While sculptures were aesthetically differentiated from real things by the use of a base or pedestal, objects were displayed directly on the floor, undifferentiated from desks and tables.

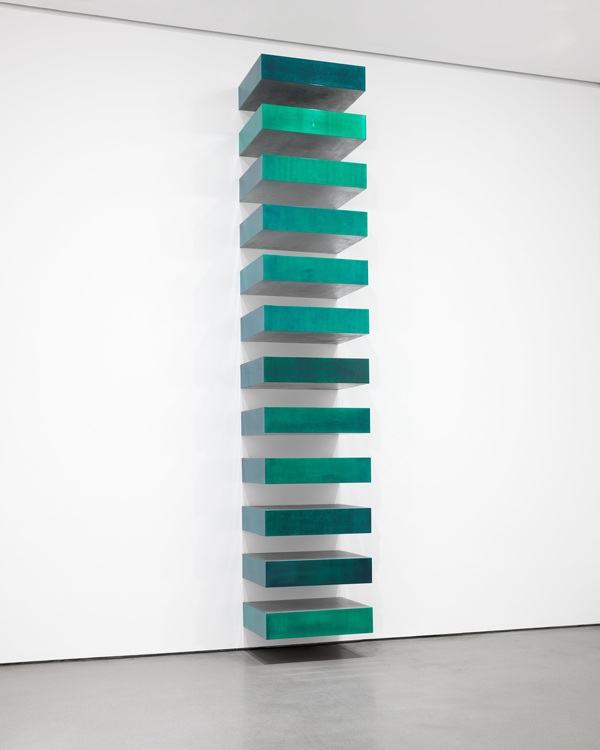

Lee Bontecou, Untitled, 1961, welded steel, canvas, black fabric, rawhide, copper wire, and soot, 6′ 8 1/4″ x 7′ 5″ x 34 ¾”, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, Kay Sage Tanguy Fund.

Rather than extending sculpture’s trajectory, minimal and postminimal objects derived from the tradition of painting, the preferred medium of modernists. The intermediary step between paintings and objects was the wall-hung relief in which the shape of the support coincided with the depicted image. In painting before the 1960s, the canvas’s rectangular frame enclosed assorted and dispersed shapes; in shaped paintings such as Frank Stella’s, the framing edge was determined by the pattern of stripes or, in Lee Bontecou’s reliefs, the protruding surface was shaped by the dark voids and copper webbing of her imagery. The shaped canvas and relief were more object- than window-like, drawing attention to the gallery space in which they were presented. Occupied by the powerful presence of a simple volume like a box, plank, or slab and a kinesthetically alert beholder, the room’s charged space is part of the artwork and the experience.

Floor Cone (Giant Ice-Cream Cone), 1962. Claes Oldenburg.

Already in 1964, Lippard was cognizant of the “anti-sculptural” trend exemplified by objects that incorporated their environment. Environmental artworks, she explained, are “extrovert” and “surround the viewer.” In addition to Judd’s first show of three-dimensional objects, her Artforum review included Stella’s “purple polygons” at Castelli Gallery (“These paintings are real objects,” she wrote) and Oldenburg’s all-vinyl Bedroom (1963), a life-size tableau of a bedroom suite. The category of environments, she noted, also included George Segal’s tableaux with white plaster life-casts of men and women, happenings performed by real people and object-based or participatory group shows. Commissioned by Arts magazine as a report on the proliferation of three-dimensional work then on view in New York, Judd’s “Specific Objects” essay identified two divergent directions: artworks that are objects and those that are “open and extended, more or less environmental.” Oldenburg was also featured in Judd’s report; soft sculptures such as Ice Cream Cone qualified as an object while Bedroom was an environment.

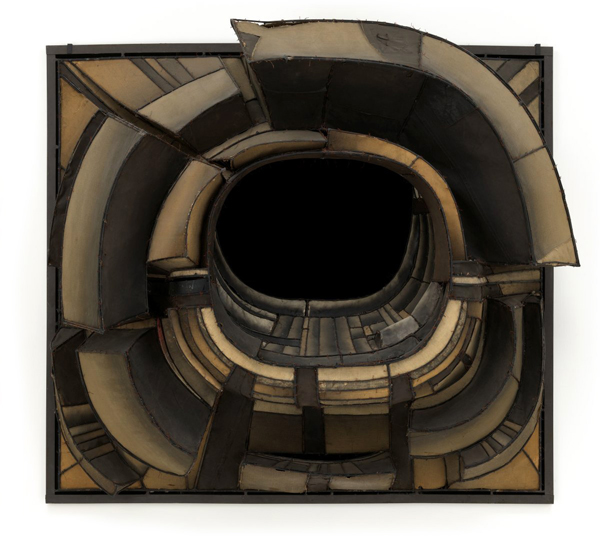

Kurt Schwitters: Reconstructions of the Merzbau, Tate

One of the most insightful but overlooked essays on environmental art is “20th-Century Period Pieces” (Arts, February 1967) by Ricki Washton (now Rose-Carol Washton Long). She traces its genesis to Schwitters’ Merzbau (1933), Rauschenberg’s combines, Kienholz’ early ’60s environmental tableaux and Lucas Samaras’ Mirror Room (1966), an enterable room with table and chair completely sheathed in plate glass mirrors, creating infinite cascades of reflections. None can be assimilated to the less elastic category of sculpture. Identifying the art environment with the popular nightclub Cheetah and the ideology of Timothy Leary (“tune in, turn on, drop out”), Washton predicted the eventual “transportation” of such period-defining rooms to museums and the unprecedented possibility that “the museum could provide empty rooms in which the artist could work out environmental settings.”

Like other perceptive critics, Washton identified Allan Kaprow’s art and theories as foundational. In his 1956 essay, “The Legacy of Jackson Pollock,” Kaprow argued that the recent history of painting led directly to the (as yet unnamed) happening, an art form he initiated in 1958. Taking Pollock’s mural-scale drip paintings as his inspiration, he explained that “they ceased to become paintings, and became environments… The entire painting comes out at the participant (I shall call him that, rather than observer) right into the room.” Happenings were entirely dependent on participants, who followed Kaprow’s lists of scripted and improvised activities in environments incorporating sound, movement, language and materials ranging from used tires to blocks of ice. Proving Judd’s point that three-dimensionality “opens to anything,” happenings and environments were widespread preoccupations of the period, represented by Fluxus, Light and Space, Japanese Gutai, late School of Paris (Georges Mathieu and Yves Klein), Austrian Actionism, Brazilian Neo-Concretism (especially Hélio Oiticia’s interactive environments), Red Grooms, Womanhouse and performance art.

This crucial juncture in the history of contemporary art marks the beginning of the end of modernism. Environments were distinguished by their rejection of one of the definitive characteristics of modern art, medium specificity, which stipulated that each medium (painting, sculpture, music, poetry) had a unique function and capability that made it the most appropriate option for an artist’s idea or expression. As critic Michael Fried sarcastically observed in 1967, “the arts themselves are at last sliding towards some kind of final, implosive, highly desirable synthesis,” as a result of the new developments that evoked the mixed or “impure” medium of theatre. Specifically targeting Morris and Judd, Fried also condemned Kaprow, Joseph Cornell, Rauschenberg, Oldenburg, Flavin, Smithson, Kienholz, Segal, Samaras, Christo and Kusama for their amalgamation of painting, sculpture, objects and environments, categories that Judd’s “Specific Objects” had carefully differentiated. While Kaprow and Washton celebrated the conglomerate environment, other artists recoiled from the non-art implications of distraction, fun and entertainment associated with everyday life. In essays and interviews, Morris stalwartly denied that his art was environmental. Flavin’s installations of fluorescent lights were also frequently described as environments, which, he said in 1967, “imply living conditions and perhaps an invitation to comfortable residence.” The raw intensity of the light and the buzzing of the fixtures were intended to be “direct and difficult.”

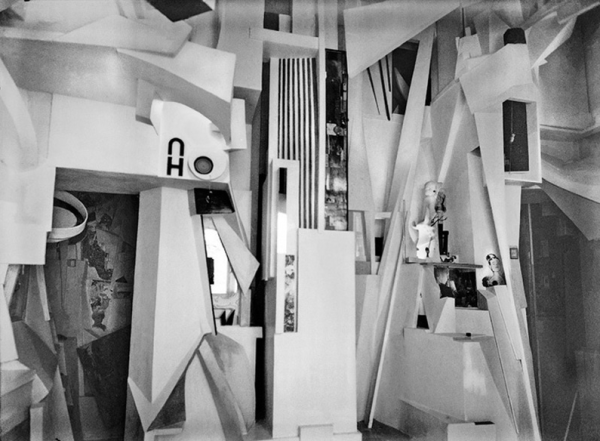

Judy Pfaff, Installation Deepwater

As readers thus far have surely suspected, “environments” became “installations” in the late ’70s. The fact that the work surrounded the viewer and required his or her participation remained definitive aspects of installations. The incorporation of the beholder’s body and its heightened kinesthetic response were more fundamental to the theory of installation art than to environments, due to the increasing influence of Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s philosophy of phenomenology. Informing but only implicit in Morris’ key text on bodily awareness, “Notes on Sculpture, Part 2” (1966), Merleau-Ponty’s interpretation of perception was body-bound and multi-sensory. The term “installation,” which had only referred to the placement and relationship of individual works of art in a gallery, now described a room-filling whole, a single piece in which the parts themselves were not detachable works. Judy Pfaff’s Deepwater—composed of painted tree branches, wire, wicker, reflective Mylar strips and swaths of bright colors like turquoise and pink—at Holly Solomon in 1980 was one of the first to be widely and without hesitation described as an installation. Here Pfaff recreated the experience of snorkeling in the Caribbean, immersing the viewer in a vibrant aqueous totality. Jonathan Borofsky’s installation at Paula Cooper, also in New York in the fall of 1980, surrounded the viewer with a seemingly random distribution of objects, a large Hammering Man, an animated video, paintings, wall drawings, even a ping-pong table to be played by viewer/participants. Tying it all together was the floor, which was littered with crumpled photocopies of a handwritten flyer found on the Venice boardwalk. Unlike the fluid, cohesive experience of Pfaff’s show, Borofsky’s was chaotic and fragmentary, conveying, he said, “the sense that you are inside my head.” By the time that Ilya Kabakov—often credited as an original installation artist—began making illusionistically convincing environments in 1983, installation was a well-established format. The term is now used so carelessly that its original meaning, which refers to the arrangement and display of independent artworks, has been conflated with the genre of art that transforms a space into a singular, experiential totality, as Claire Bishop has pointed out.

The same linguistic laziness affects our use of the word “sculpture,” which is applied to any three-dimensional work of art, including installation. Just as Duchamp deplored the identification of his readymades as sculpture and object-makers were purposefully not sculpting, most three-dimensional art is not sculpture in the original sense of the word. Overcoming the limitations of sculpture, objects and environments have prevailed for the last 50 years.

Not until the ’90s, according Roberta Smith’s analysis of Judd’s early innovations in 2002, was sculpture once again viable. Robert Gober, Kiki Smith, Charles Ray and Jeff Koons, to whom I would add Rachael Harrison and Isa Genzken, reestablished the medium of sculpture. Their figurative or anthropomorphic compositions convincingly affirm the sculpted statue of yore.