At Kandis Williams’ studio, sparse and white with tall ceilings and drywall divisions, her studio neighbor Orion Martin and I sit and talk with her about contemporary intimacy. I am struggling as to whether I should revive a Tinder account in an act of hysteria spawning from a relationship that cut far too deep for its brevity. Williams shakes her head, empathetic and saddened.

Alphonse Mucha’s “Slav Epics”

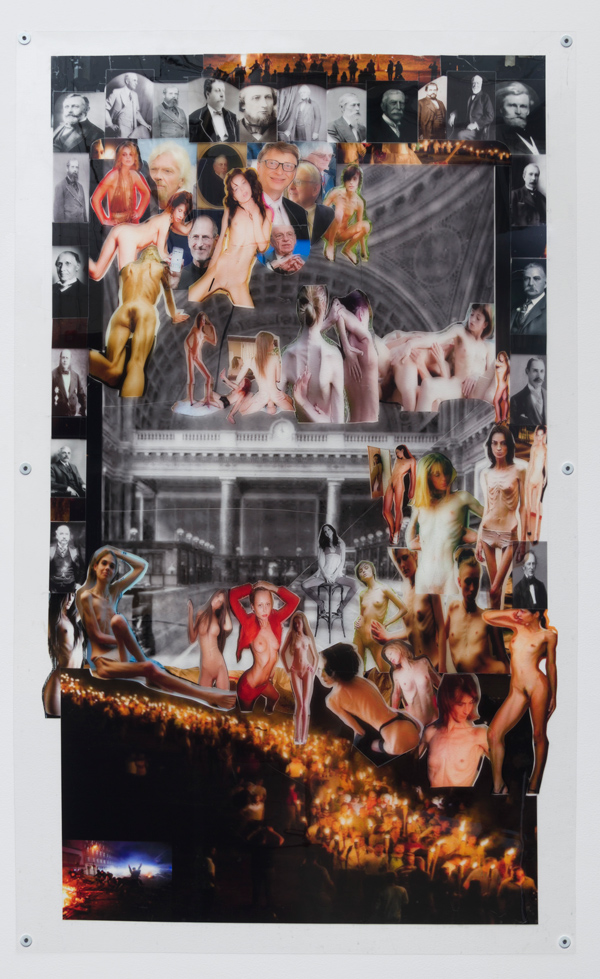

Williams is at the time working on some large-scale collages—featured in last October’s art fair Frieze London—based on epic historical painting, Czech Art Nouveau painter Alphonse Mucha’s “Slav Epics” in particular, but populated here by anorexic women and the antipathetic beasts of modern economy, simultaneously sexualized and horrific. The figures morph and climb, amid skeletal orgies in the interior court of the bombastic neoclassical First National Bank in Philadelphia, with Bill Gates, Richard Branson and Steve Jobs cast as little angels hovering assuredly in the upper peripheries. There must be some sort of analogy to be had with the hilarity of Polish artist Jan Styka’s Crucifixion (1894)—the largest framed and mounted canvas painting in the world, a sprawling and kitsch Passion of the Christ—squeakily unveiled at Forest Lawn over the Los Angeles skyline every day, a skyline which only this summer, to the northeast, was literally filled with flame.

Jan Styka’s Crucifixion (1894)

The material quality of the collages, too, compels a sense of dread, the granulation of digital enlargement and gloss of the vinyl she incorporates in broad swaths, as sadomasochistic and dystopian as “shiny-floors shows” (the industrial term for the catatonia-inducing platform behind Strictly Come Dancing and The Voice), the figures decomposing in a hyper-reality of subverted and subversive media reprinted and dismembered. Traveling mainly between lives in Los Angeles and Berlin, she now manufactures some of the elements of her work through production trips to Mexico, supported by various friends and galleries. This transnationalism brews a terrifying spectacle in its synthesis, the various elements colliding with and collapsing upon each other—an eyeless Bulgarian mystic embraced by the spit of a computer; a holocaustic webcam girl being split apart by a massive cock while bearded 19th-century big-banking forefathers look on. In The Midnight Snack, one of the other recent works, a serpent decal produced in Mexico is stamped unmistakably over by U.S. currency; the surface is reflective.

Mothers and sisters…, 2017

She and I sit in the grass by Echo Park Lake the next week and talk very calmly about the end of the world and what it could mean if that didn’t occur, per the writings of the Invisible Committee. Williams has for many years published and contributed to radical zines and workshops, primarily dealing with aesthetic philosophies of race and the body. She brings up the Wiener-Hopf method, a sequence of equations she’s become interested in that’s used in the analysis of outcome, particularly with stocks but even—her main area of interest—sociologically. She explains that the Wiener-Hopf predictions—which, in brief, determine a specific solution to equations with semi-infinite variables—are “subject to chaos.”

The genesis of her most recent themes is a self-described obsession, the analysis of Simone Weil in Chris Kraus’ Aliens and Anorexia and Tiqqun’s Preliminary Materials for a Theory of the Young-Girl slowly forming an image of the totemic female “nestled in advantageous proximity to power,” in relation to invisibility, to control, to some extent to mortification. “A good amount of history and literature about economics and philosophy has been told by the people with the least connection to it,” she says. She later redacts this, vigilant against coming across as simply reactionary or pedantic.

Night Gallery installation view, Frieze London, 2017

Describing an experience in Northern California as we look out at the Monetesque landscape of the park, she tells me the story of a well-groomed white man introducing himself as a farmer. “No,” she says, “the man behind him, the brown man with his hands in the dirt, he’s a farmer.” Throughout her stay there—working for a time as a waitress at an old rancher bar, next door to the iconic white country church in the town where Alfred Hitchcock shot The Birds—she describes people being amazed by her presence, her very being. Parents would come in from the surrounding counties to introduce themselves to this new young black woman, giddy that they could now tell their daughters who lived in the big cities that they “had friends like her.” Some of the service staff, however—a chef from New York, and a Wiccan single mother of two—predictably offered the eclectic solidarity of too many years of compelled hospitality, there amidst the tableau of hedge fund pot-tourists and decades-old racism.

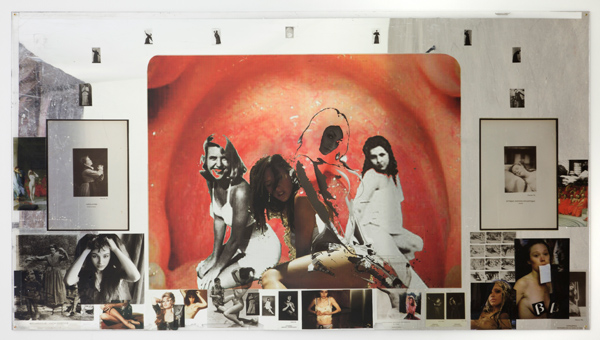

Kandis Williams, Esophagus Pin Up, 2016, courtesy Night Gallery.

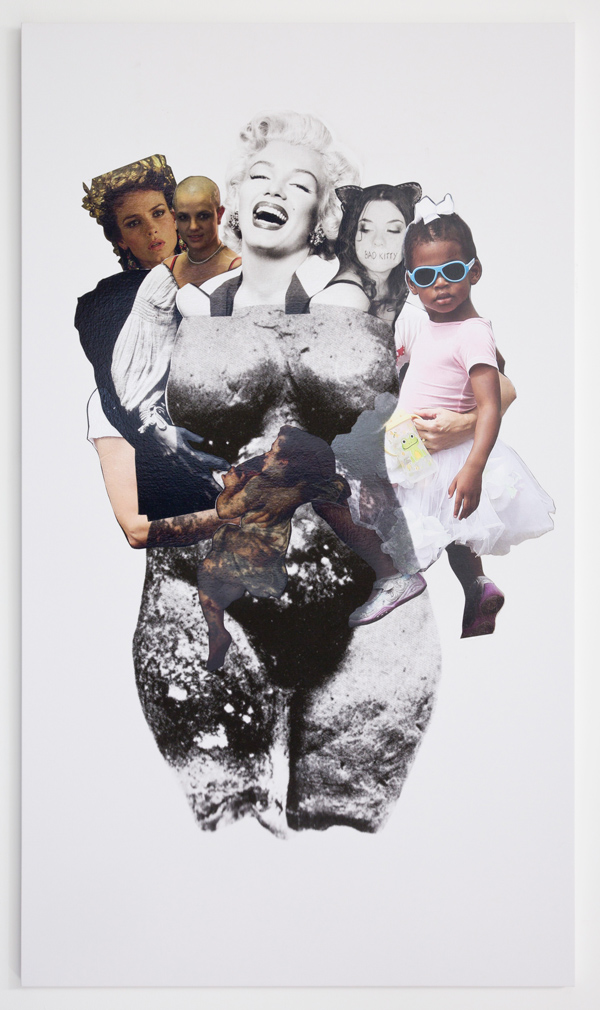

Always in her work these experiences ring through. Rarely do the subjects appear in states of overt violation; on the contrary in fact, they often seem to relish the display, or seem at the very least complicit. Any number have been celebrities: Fiona Apple preening in the “Criminal” video in Esophagus Pinup, Britney Spears in her Frances Farmer moment, grinning blissfully at the cameras with a shaved head, and Marilyn Monroe offering everything that’s been built into Marilyn Monroe in Venus is a Sacrificial Form. And yet there is in each of these figures a gnawing and urgent undercurrent of disturbance, of frenzy, of the terrible bond between repulsion and desire being played out endlessly in their relationship with the spectator.

Kandis Williams, Esophagus Pin Up, (detial) 2016, courtesy Night Gallery.

In her personal notes on the recent work displayed at Frieze London, she places the word “Vorstellung” at the top (the German word meaning an image formed from the “prior perception of an object,” not the tangible experience). This is the screen memory or parallax view Williams’ arrangements seek to magnify; that grotesque line between hatred and lust, the unacknowledged reconciliation of sickness, visibility and the object.

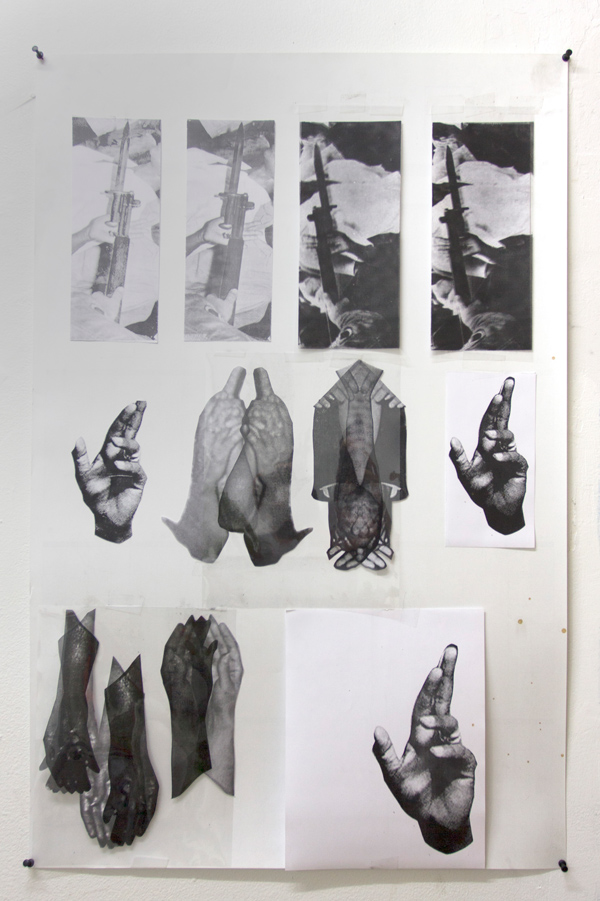

One must note, and make no mistake, that nearly all of these women in her collages are white. In different phases of her work “the dauntlessness of the concept of ‘black’ as material” (from her notes) has been featured often and prominently, most of the previous works printed very literally in black and white; recently, however, a black body will appear only occasionally as a prop or anomaly, and never unintentionally or whole. The compositions in which they do feature, both now and before, are often fractured well beyond the manipulation of their white counterparts: her father’s face is pieced apart in Separation, Temptation Blake Son until only a childhood photo of her mother remains unadulterated on the fringe; Malcolm X’s finger eternally objects without the man himself instructing its movements in The Oratory Command: X Carmichael King Hampton.

Sketch Come Up, Hold Down, 2016

Most of the black presence in her current work appears live, confronting, moving in space. “Performances aren’t hyper-negotiable… [there is] a visible discourse of authorship with the other artist,” she says: an authorship that has been in most cases, or historically, dictated externally. The performers are often labored, in states of extremity or mortis.

Intriguingly, when white performers, specifically women, have been part of the live iterations people generally ignore them, while black bodies, she observes, are approached and commented on as “normalized spectacle.” She tells me that in a write-up of a radio segment about her work, the commentator claimed that the choreography was “going for the jugular of white men”; she laughs.

Venus is a Sacrificial Form, 2016

Growing up in Park Heights, Baltimore, a neighborhood “mentioned in songs with gunfire samples,” Williams saw the living death, this constant edge of force and alienation firsthand. “My grandmother has seven sons, all of whom have been in jail,” she says. One of her first jobs was at ADT, the alarm company, telemarketing security systems to more affluent white residents, mapping violent crime as a selling point.

Arendtian Death Mask, 2016, collage on drywall

vinyl adhesive on Plexiglas.

And when, in a recent show at SADE gallery in East LA, she pictures Hannah Arendt exploding into a death’s head, it’s hard to escape that we are living in the paradigm of one of Arendt’s ideas—that when there is power without consent, it reaches almost inevitably into violence. Simone Weil as well, in The Iliad, or The Poem of Force, says that a life either with a constant need to impose force or risk annihilation or, alternately, with the constant fear of force is not living at all, it is a hollow stasis: “Here, surely, is death but death strung out over a whole lifetime; here surely is life, but life that death congeals before abolishing.”

Back in my room, Williams texts me chastisingly for watching Scandal, its frivolous depiction of a “Sally Hemings Barbie spy” disturbing her to no end. We joke and I remain prone; a man yells outside.

Shonda Rhimes aside, there are things worth being angry about, and Williams continues to confront them head on.