Who doesn’t like a bit of mystery? But where are they keeping it these days?

There are certainly unknowns—when will this pandemic really end? Did they really do that? But mystery is not the same as a mystery. True crime, for example, isn’t mysterious. In the end either one kind of crime was committed or another was. If the killer is eventually revealed, it’s extremely satisfying… and far less mysterious. A true mystery feels mysterious every time you see it.

True mystery gathers around something unknowable but compelling: fields of humanoid fossils in the Rift Valley, incunabula deep in the Bodleian or Vatican libraries, the heart of the sun.

Any art old enough to also be an artifact can feel mysterious just by dint of having been made by long-vanished minds we’ll never have a chance to know—but newer art summoning mystery is a neat trick. Francis Bacon did it, after so many surrealists failed, perhaps because his distortions seemed so necessarily to connect to pain (so less playful), Lee Bontecou did it (she made the biotechnohorrorvoid as abstraction before Alien made it literal), Mark Tobey was mysterious on a good day. But, aside from a few aggressive antifashionables like Jeronimo Elespe and Danny McCaw, “summoning mystery” tends not to be on the contemporary artist’s list of ambitions. Why?

For one thing, we live in an age of explication. Seconds after hearing about a thing for the first time, we are googling up a gloss on it. The truth is out there, or at least several plausibly mundane competing theories. We use explication in so many ways: explication-as-advertising (for the explicator or the explicated), explication-as-entertainment (What happened at Chernobyl? Who is this Tiger King?), explication-as-critique (or, more commonly, backdoor insult).

For another thing, it’s really hard to be both mysterious and funny—and since at least Warhol, it’s been hard to accuse anyone of genius unless they have “wit.” Giving up on wit looks like giving up on self-awareness, and in an age of social media that’s the only defense most of us have.

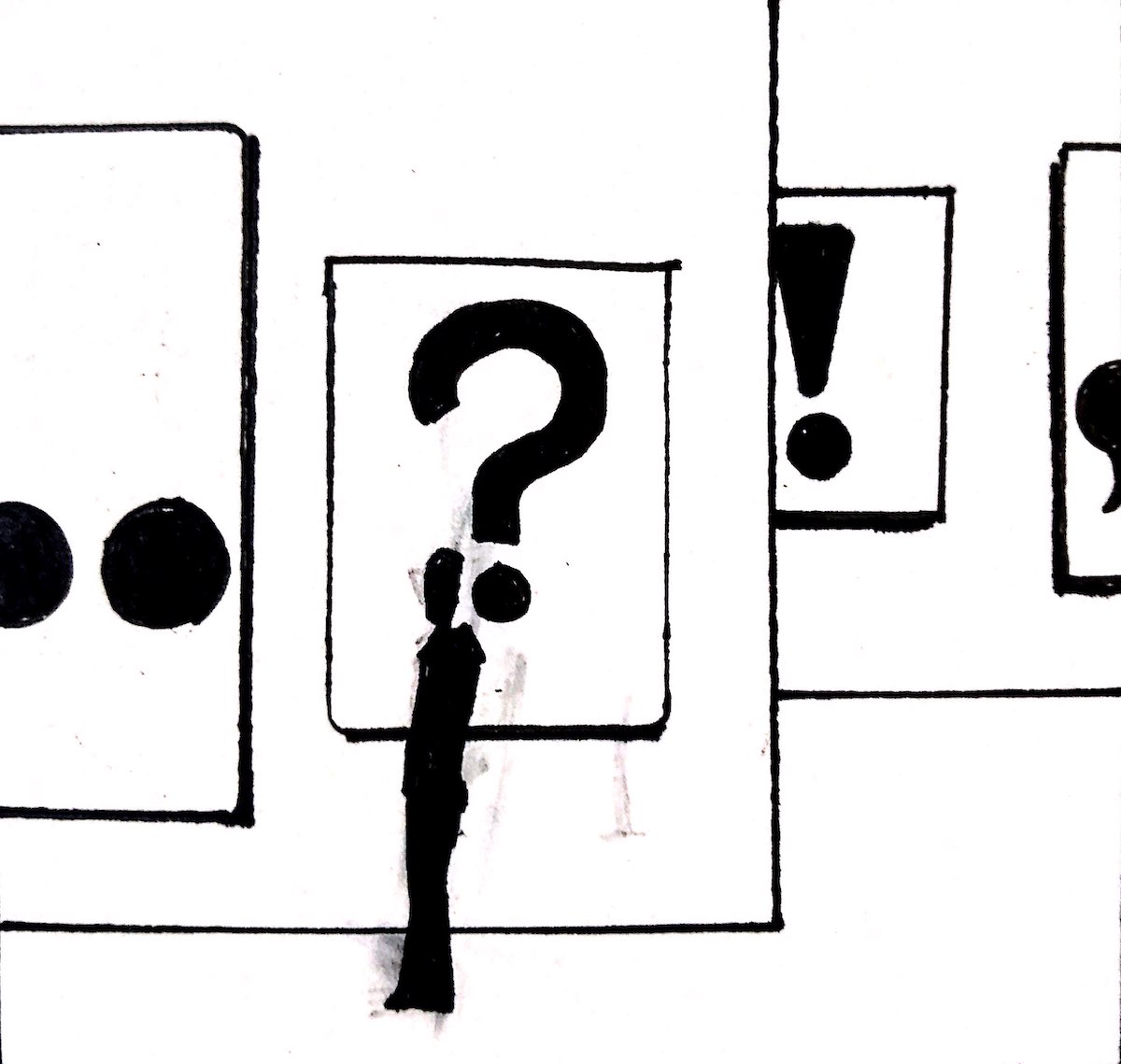

Illustration by Zak Smith

Science and the fictions science engenders seem less mysterious every day: our current style of public speculation tends to be less in the direction of what? and why? and more in the direction of how soon will we solve it? and how horrible will we be about it when we do? Science seems increasingly about us. About what kind of bad will we be with our new machines and new genes? Nothing could be less mysterious.

Is our music mysterious? Hip hop is the least mysterious form: the thrill has always been in how blatant it is. The orchestration and collage required of electronic music, on the other hand, can be mysterious, but it always seems to need help: a dancehall, a drug, a movie—it needs to be part of a larger dream.

Dreams will never go anywhere: that’s a good sign, for mystery. But are we putting any stock in dreams these days?

Religion is dream-adjacent, but lately we understand religion primarily as a social divider or a form of self-help—which makes it eager to explicate itself. Faith behaves now as if its survival depends on being de-mystified. Artists in Western Europe stopped asking Why the Crucifixion? and Why the Resurrection? in the middle of the last century and the rest of the world is far too practical to spend any time wrestling with such things. Maybe in Latin America? But there the low-hanging peach flesh of infinitely discussable topics like gender, sexuality and colonialism are always close at hand. Issues are not mysteries—issues are vital, urgent, they have right and wrong answers, they can get you killed. It’s not safe to get caught messing with the ineffable when there are issues afoot.

This points to the absence of the most mysterious thing: god. Which I’m fine with, really, but you can see why people try to find substitutes in star charts or tarot cards: there is a dark and luxurious sense of privacy, intimacy and infinity that takes over when you become convinced that something really depends on how you handle being alone in a room with a metaphor.

To be pressed to puzzle out the truth from inert and inarticulate matter in a way no expert or psychiatrist could know better than you—that’s tremendously exciting. I would like more artists to try it.