“No one achieves frivolity straight off. It is a privilege and an art; it is the pursuit of the superficial by those who, having discerned the impossibility of any certitude, have conceived a disgust for such things; it is the escape far from one abyss or another which, being by nature bottomless, can lead nowhere.” — E.M. Cioran

William Minor appeared to be elegantly communing with the muse as he leaned against a tree outside a hillside bistro that does particularly good business at happy hour. As I walked up, he discreetly directed my attention towards one of the tables, at which an actor from what has sometimes been referred to as ‘the greatest television series of all time,” was drinking among friends. Having finally got around to watching the entire five seasons of that show during the pandemic, I was struck by how star-struck I was. Minor was also moved, and tenderly spoke the lovably ill-fated character’s name.

Every sidewalk table was occupied, so we went inside and made ourselves comfortable in a corner booth. They were out of Kronenbourg but Minor, a poet who sees beauty in everything, readily acquiesced to the waitress’s suggestion of a different lager.

“What happened with that English press?” I asked, referring to our last conversation, when Bill had mentioned that a reputable imprint had expressed interest in publishing his next book.

“I never heard back from them,” he said in the cheerful tone of one who is long-inured to the fickle nature of the publishing business. “Rarely will I submit anymore.”

“Don’t despair,” I said. “If you keep trying, maybe by the time you turn 80, Poetry magazine will accept one of your submissions, and just imagine how gratifying that will be. All the years of struggle will turn out to have been worth it.”

“That’s not what I meant by submitting,” said Minor.

“I thought you were talking about the completely pointless exercise of submitting to those literary quarterlies that nobody reads. Never mind. One values one’s work more if one receives no tangible reward for it.”

“Whether anyone else does is another matter,” said Minor. “This lager is weak,” he added.

The waitress reappeared, and turning on his not inconsiderable charm, Minor asked her to recommend a good mid-range Bordeaux.

If a man should ask to meet me

at the summit of a mountain

to discuss the great questions of life,

I would have to turn him down.

“The only reason that poets read the work of their contemporaries is to satisfy themselves that it’s not as good as their own,” said Minor.

“Guilty as charged,” I said. “It can be very annoying on the rare occasions that one stumbles upon something good. As Godard said, ‘Poetry is a game of loser-take-all.’”

“It keeps me alive and amused,” said the ever-magnanimous Minor. “I mean, writing is fun. Why bother otherwise? When I read Gertrude Stein, or even Cioran, I feel the pleasure they’re experiencing.”

In Minor’s work, the pleasure is also palpable and infectious. His rarefied irreverence and whimsical quirks of logic induce a singular sort of laughter. The distinctive charm of these polished gems, chiseled from slabs of thought and applied with a light touch, arises from manicured compression. Divested of their initial narrative and psychological context, the resulting dislocated humor takes economy of language to new lengths. Rarely exceeding five lines, these poetical bon mots read like asides but gather power when read en masse.

Language can be very exciting

when a woman you’re interested in

tells you something you were hoping

to hear about yourself.

Ten minutes later, before he had drained his first glass of wine, another was requisitioned. One and a half glasses of wine and half a bottle of beer now sat before the poet. They would all be drained.

“Are you a natural-born miniaturist?” I asked.

“It’s a crystallized form of something richer,” said Minor. “It needs to survive without the clutter of other sentences attached to it. The beauty of minimalism is in the things you leave out. Minimalism has an innate humor to it. If you strip things down, there’s always an element of humor.”

“I’ve never thought of it that way before,” I said, struck by the apparent soundness of this statement. So that was the truth about minimalism.

“Are you taping this?” asked Bill.

My phone was on the table but the tape wasn’t running.

“No. That’s way too much work, and I don’t like the sound of my own voice. So, off the record, how were you lured into the glamorous world of poetry? Was it the easy money, the pliant women, the pleasures of life on the road?”

“It chose me. I wish it had chosen somebody else, to be honest,” Minor admitted. “What about you?”

“A desperate last resort.”

A courtly Southerner, Minor was something of a teenage musical prodigy; he almost joined a later incarnation of Lynyrd Skynyrd after trading licks with their guitarist, Gary Rossington, at a biker bar in his native Jacksonville. Poetry entered Minor’s life via philosophy, which he studied at Florida State. A period of intensive literary immersion followed, throughout which the pallid Floridian lived in New York and London. Such names as Satie, Jarry and Michaux flow freely throughout his conversation, and if anywhere, it is in the spirit of these idiosyncratic eminences that his work resides.

“So why didn’t you pursue a musical career?” I asked, sipping my second tequila and soda.

“The biography of a poet is never interesting,” stated Minor.

Sometimes a poet writes about something interesting

and then something interesting happens to him.

Sometimes something interesting happens to him first

and then he sits down and writes about it.

Anyhow, nobody cares.

“’True poetry will die on the day that poets overcome their envy of artists and musicians,’” I quoted.

“Who’s that?” asked Bill.

“Rafael Rubenstein.”

“Never heard of him.”

“Neither had I, but on the strength of that quote, I sent him one of my books when it was published. He never wrote back. I couldn’t help noticing,” I added, “that a blurb from Harry Matthews graces the back of your latest collection. How did that come about?”

“I was in Key West during a tropical storm. Everything was shut down and I was walking the streets. I ducked into a bookstore and saw some Harry Matthews books on display. I was told that he was a part-time resident, and I thought it would be nice to meet him. I found his address in the white pages. He lived next to a cemetery. His wife answered the door and invited me in. I was soaked through. I noticed a copy of Andre Agassi’s autobiography on the shelf. He told me he had read it twice. We sat and smoked together and talked about tennis. Through the window we watched iguanas crawling into the swimming pool. He spent winters in Key West, summers in Paris. Yes, he’s independently wealthy, very gracious. Two years later, out of the blue, he contacted the publisher of Pigeons, and that turned into the blurb.”

“Have you ever noticed, when you’re reading a biography of a poet,” I chimed in, discordantly, “how often their freewheeling lifestyles are exhaustively catalogued but how they were financed is rarely addressed? These writers often come across as magical beings who seem to float around the world without financial encumbrances of any kind; inheritances or allowances, if they are mentioned at all, are always ‘small’, yet they always allow their beneficiaries to live without having to resort to employment. Elizabeth Bishop, Ezra Pound, ee cummings, the list is endless.”

“Baudelaire never had to punch a clock,” said Bill, and he excused himself to walk outside and feed the meter.

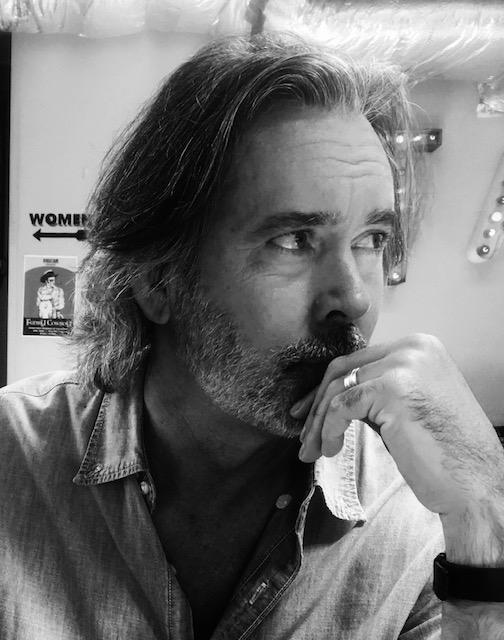

Photograph of William Minor

There are more pigeons surrounding the river

than there is darkness surrounding the pigeons.

Upon Bill’s return I asked him if the actor was still out there.

“Yes,” said the poet, musing over the strength of the actor’s bladder: “He’s still pounding those light lagers. I can’t believe he hasn’t taken a leak yet.”

“If he had, we’d know about it,” I said. “He would have passed us on the way to the restroom.”

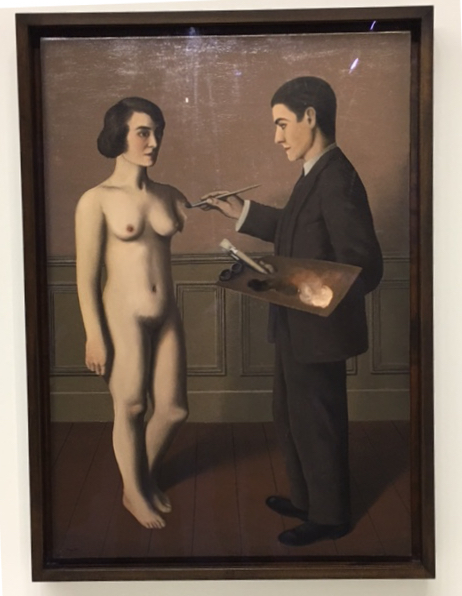

Minor’s work seldom appears in magazines, although three of his four slender volumes of poetry are still in print. Pigeons and Pussy, alternates between observations on the titular subjects and is guaranteed to induce fits of irrepressible laughter when picked up by the casual browser. The Balthus Poems uses the painter and provocateur as a medium for Minor’s playfully perverse wit; and the latest, Pieces in the Form of a Pear, named after a Satie piano composition, runs the gamut of the poet’s preoccupations: Love, art, philosophy, horses and fruit.

Foredoomed by the form he has chosen, Minor has doomed himself further by committing the critical sin of being accessible to the so-called layman. That his work is also entertaining makes him even more of an outsider in the prosaic world of contemporary poetics. If he experienced any worldly success, he would probably be accused of getting away with murder.

When my thoughts

turned to the darkness

of the river, my thoughts

turned deeply to pussy.

“If you say you’re a poet,” said Bill, whose poetic brevity is often belied by conversational garrulity, “the first thing people ask is ‘are you published?’ If not, it’s considered a pretentious proclamation. But if somebody tells you they’re a musician, you take their word for it; you don’t ask them if they have a record out.”

“Music does seem to possess an almost unfair advantage over the other arts,” I said. “As Walter Pater observed, ‘All art constantly aspires to the condition of music.’”

“We must defer to it,” said Bill, “owing to its transcendently abstract qualities.”

“With music, or even, to some extent, literature, obscure figures are constantly searched out and revered,” I said. “It’s not like that in the realm of poesy, where no value whatsoever is placed on obscurity.”

“But obscure content is valued,” said Bill. “Poetry itself is frequently prized for its obscurity and opacity.”

The easiest way

for a philosopher

to lose his meaning

is to lose it in the mind

of another man.

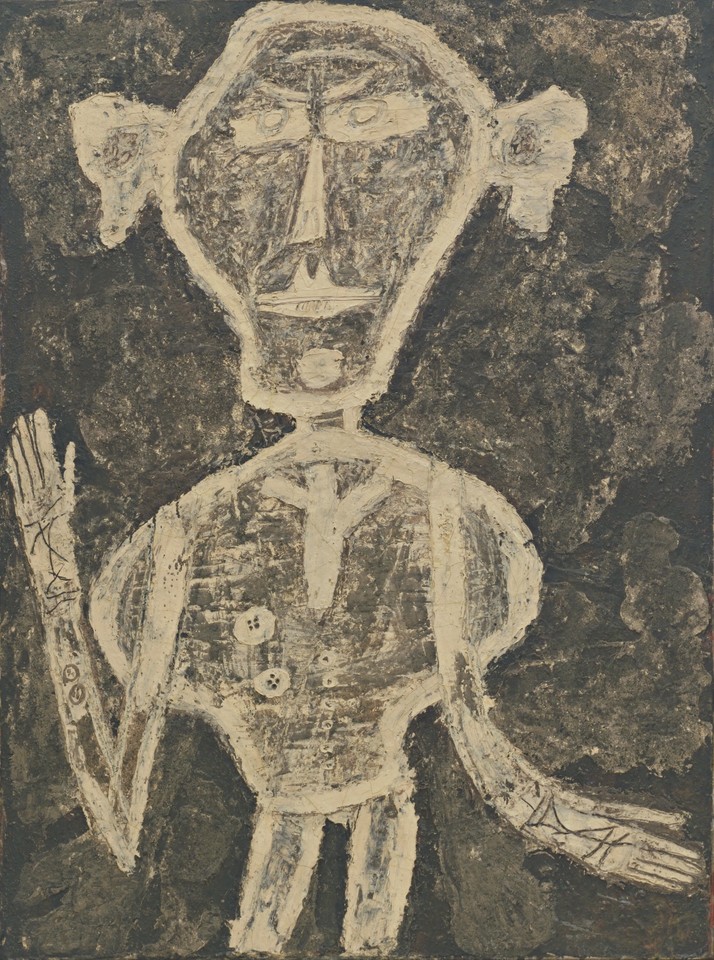

Jean Dubuffet – Portrait of Henri Michaux (1947)

Bill ordered another glass of Bordeaux. “I should probably switch to the cheap stuff,” he said. “I have to attend a concert later. I went to see Patti Smith the other night.”

“I’m sorry.”

“It was free, and my expectations were so low that it was surprisingly enjoyable.”

“No offense,” I said, “but isn’t she living proof that a minor poet can become a major songwriter? It’s funny, isn’t it, that the phrase ‘a minor poet’ is so prevalent, when one never hears of minor novelists, minor painters or minor musicians? It’s bad enough being a so-called poet in the first place, but then you have to endure the added indignity of being labeled a ‘minor’ one, unless you are one of a very select few.”

“The thing about being a minor poet,” said Bill, “is that you have to be a fairly substantial major poet of your own era just to achieve the status of becoming a minor poet. Think of all the poets out there, many of whom may be quite well-known, who are never going to achieve that status. To become a minor poet is a towering achievement. Historically, it means that you were relevant enough to at least be on the margins.”

Inner meaning is fine,

but it can lead to the falsification

of other types of meaning,

the kind that occur in most landscapes,

for example.

“Leonard Cohen was trying very hard to get laid,” said Bill, sticking to the subject of minor poets who became major songwriters.

“You can really hear that in his early songs,” I said.

“He made this unforgivable transition into music,” said Bill.

“Oh, he received plenty of forgiveness.”

“It’s unforgivable in the literary world,” said Bill. “There are segments of the literary community who see nothing of value in his work.”

“Yes, but if he’d stuck to poetry he wouldn’t have made any money, and he wouldn’t have got laid nearly as much. He moved far beyond such concerns. There are segments of the literary community who see nothing of value in anybody whose work is popular and accessible. Did you watch that recent Leonard and Marianne documentary? The women that were throwing themselves at him backstage. I’ve never seen anything like it.”

“In the long term all of that is irrelevant,” said Bill. “Down the road the only thing that’s going to matter is if the work is any good. All that other stuff will slowly dissolve.”

At this point, conversation drew to an abrupt halt as the actor entered the room, and sauntered coolly past us into the restroom.

“Finally,” said Bill.

Less than a minute later, the actor reemerged.

“Fuck, that was quick,” said Bill.

“An alarmingly quick debouchment, considering how much beer he’s put away,” I said. “It’s been over two hours, and who knows how long he was here before we arrived.”

“He hardly had enough time to piss, let alone wash his hands afterwards.”

“He definitely didn’t wash his hands.”

“Quite remarkable.”

It is a sacred thing

to look at a man sitting at a table,

provided you are no longer

a man yourself, and he isn’t trying

to tell you a story.