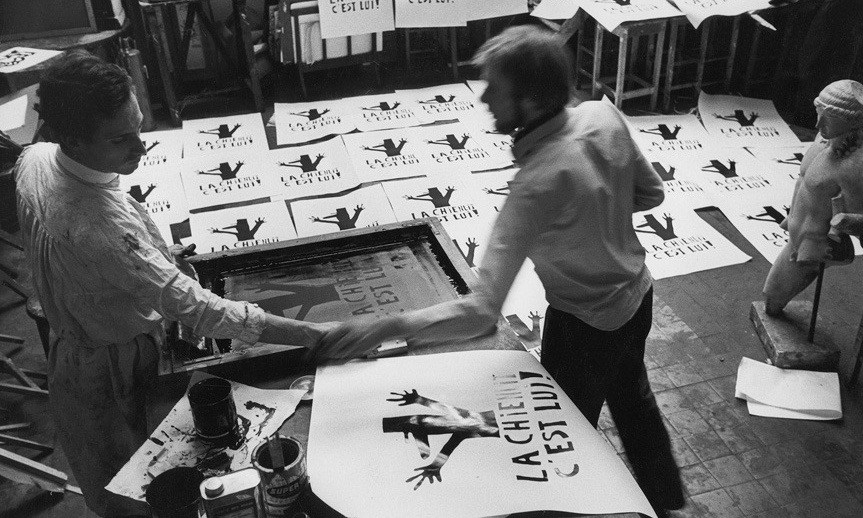

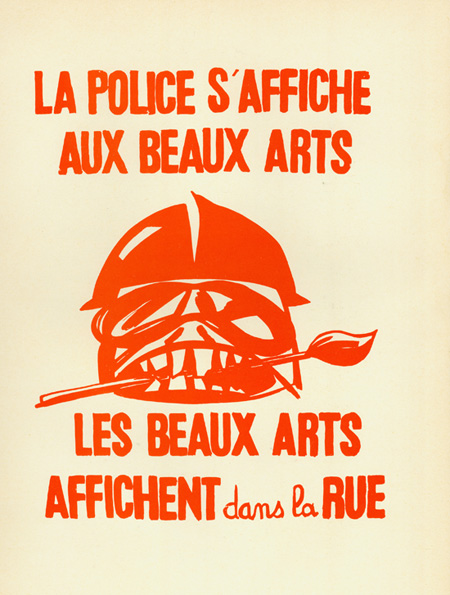

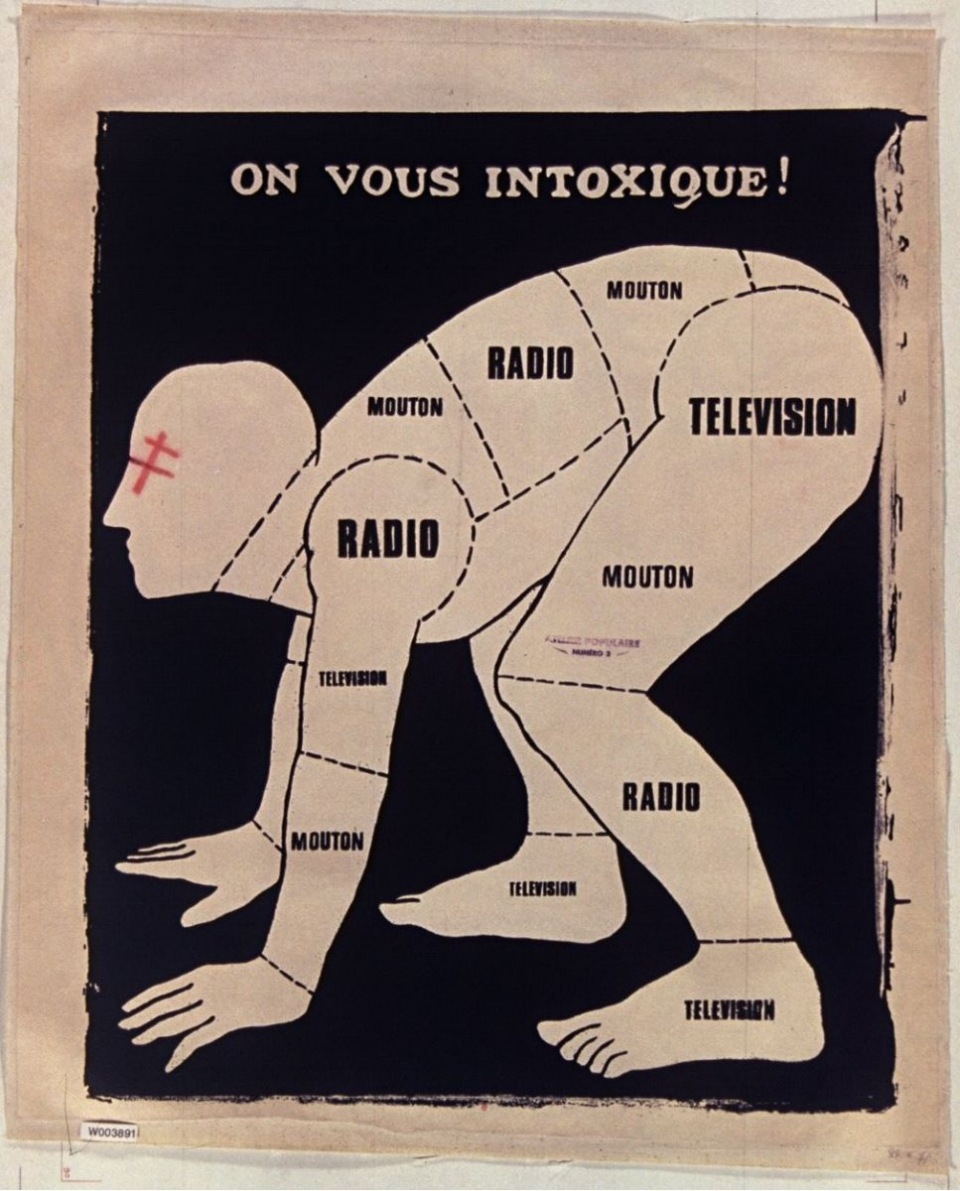

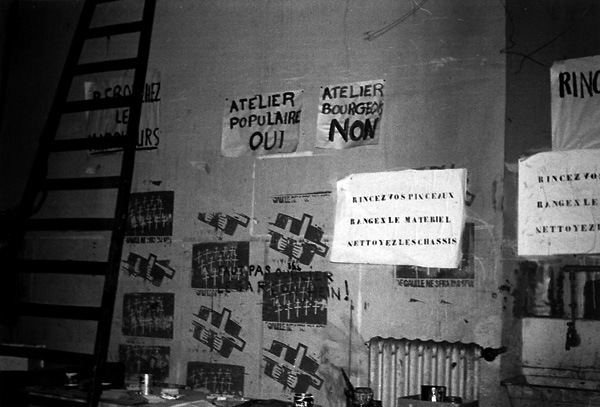

May marks half a century since the student and worker protests against rising unemployment and poverty under Charles de Gaulle’s conservative government in France. In May 1968, students and faculty at the L’ecole des Beaux-Arts took over the lithography studio and established the Atelier Populaire (the Popular Workshop). Their collective produced hundreds of pop-derived silkscreen posters, which remained an object of obsession for the art world, despite the creators’ insistence that they should not be viewed as artworks. Nevertheless, the posters are useful documents that captured the clashing ideals of a political moment and held a meaningful relationship with social and historical realities.

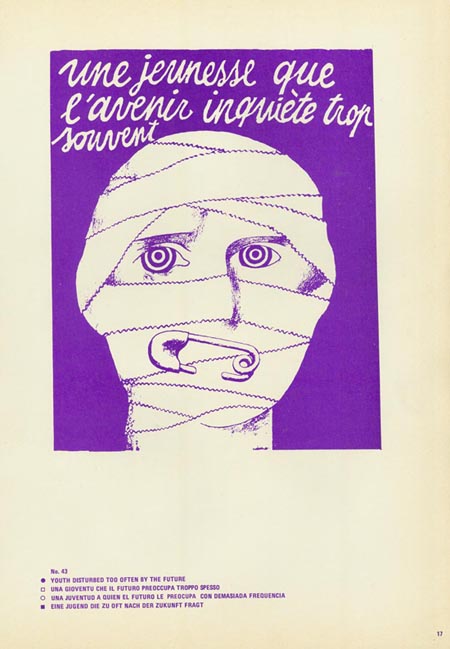

The posters juxtapose weaponized language with youthfully playful images. The motifs of hands and machines are frequently featured, as are statements lamenting the disillusionment of a collective French youth. In one of the most iconic, a bandaged face with an agonized gaze is featured above the text: “Une Jeunesse Que L’ Avenir Inquiète Trop Souvent” (A Youth Disturbed Too Often by the Future). Individual artists were not credited, and each poster was seen as the work of the collective, which voted on which posters to use.

-

-

-

-

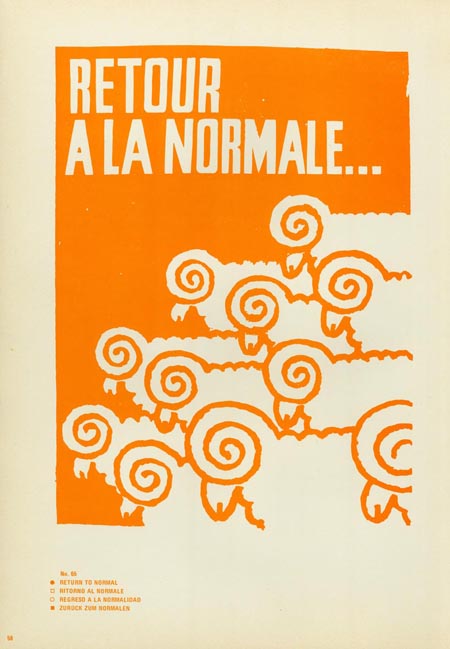

"Return to normal"

-

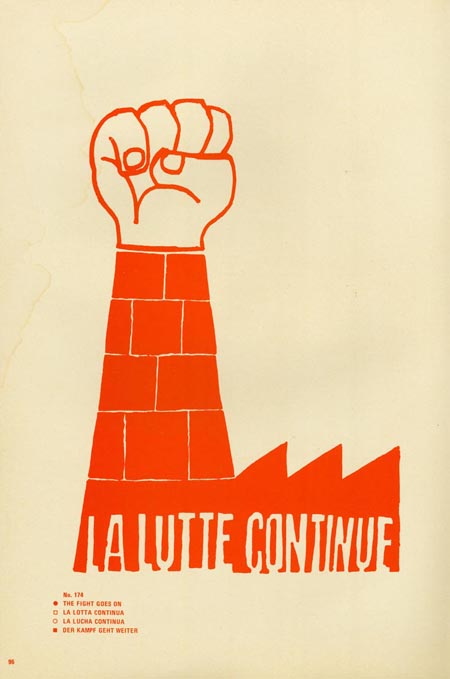

"The struggle continues"

-

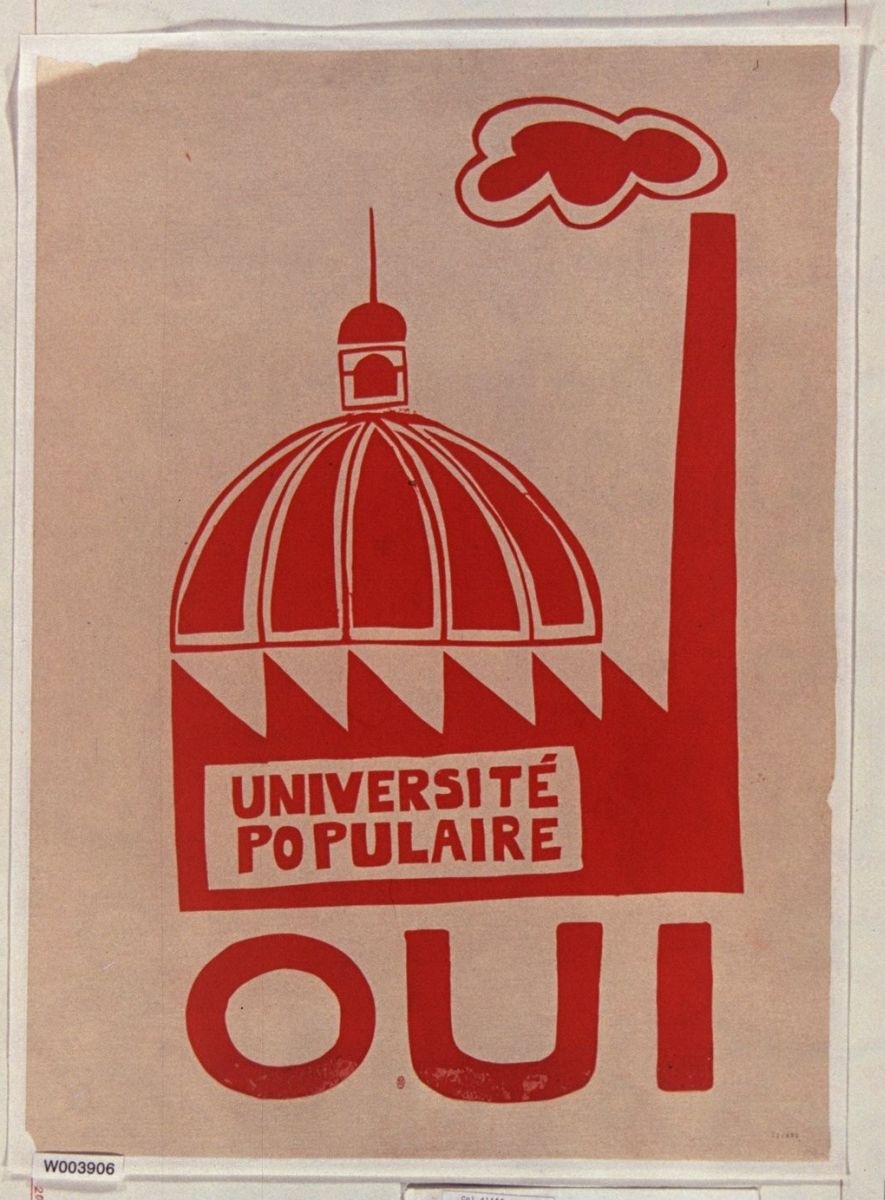

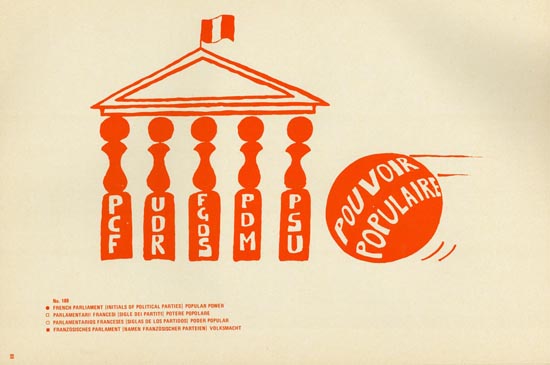

“Popular power,” with the initials of France’s political parties on the columns

-

“A youth disturbed too often by the future”

In the front of a 1969 volume, Posters From the Revolution, the Atelier Populaire made a collective statement:

“To the reader:

The posters produced by the Atelier Populaire are weapons in the service of the struggle and are an inseparable part of it.

Their rightful place is in the centres of conflict, that is to say in the streets and on the walls of the factories.

To use them for decorative purposes, to display them in bourgeois places of culture or to consider them as objects of aesthetic interest is to impair both their function and their effect. This is why the Atelier Populaire has always refused to put them on sale.

Even to keep them as historical evidence of a certain stage in the struggle is a betrayal, for the struggle itself is of such primary importance that the position of an “outside” observer is a fiction which inevitably plays into the hands of the ruling class.

That is why this book should not be taken as the final outcome of an experience, but as an inducement for finding, through contact with the masses, new levels of action both on the cultural and the political plane.”

While galleries throughout Europe have purchased the posters and featured them in countless exhibitions, the inclination to read them as artworks rather than political ephemera indeed feels misguided. However, considering the goals set forth by the comrades themselves — bearing historical witness, assisting in the finding of new levels of cultural and political action — the posters were arguably successful. It holding any aesthetic interest in them a tacit betrayal of their use?

This was an ongoing conversation among the Atelier Populaire. Quotations from Guy Debord’s The Society of the Spectacle were featured on posters and graffitied on Parisian walls:. The Debord-Benjamin tradition warns against the tendency of political aestheticization to divert attention away from the practical goals of protest, instead favoring spectacle. Simultaneously, The Situationist International (the Situationists), a group of avant-garde social revolutionaries who played an important role in the uprisings — and with which Debord was affiliated — rejected the separation of artistic expression from politics and current events on the grounds that it was an attempt by the establishment to dismiss art featuring apt societal critique.

Even when considering the posters as political tools, their aesthetic strength and consistency are crucial components of their effectiveness. They also provide historical demonstration of how artistic and cultural expressions can be transformed by political urgency. Because of the pace of the events of the uprising, the Atelier Populaire strayed from traditional beaux-arts mediums like lithography and offset printing, preferencing the expediency of silkscreening (which was not taught at the fine arts school and was infrequently used by artists). The collective distributed a text detailing the steps of the silkscreen process, and worked in a manner similar to an assembly line. This connection with labor was deliberate — the Atelier Populaire rejected the elevation of artists above workers as myths put forth by the bourgeoisie and the French Ministry of Culture and kept the problems of the working class at the center of their objectives. In a manifesto, the group wrote, “We want to be clear that it is not a better relationship between artists and modern techniques that will better align them with all other categories of workers, but an opening to the problems of the workers — to the historical reality of the world in which we live.”

École des beaux-arts: ‘Atelier Populaire Oui!’

What about art’s ability to function as a medium for activism? The unified voice that is essential in protest often feels divorced from a clear artistic end. As Susan Sontag wrote in her essay on Cuban protest posters, “posters and public notices address the person not as an individual, but as an unidentified member of the body politic.” When considering the recent resurgence of activist-art, and activism by artists, the distinction is key. Boris Groys writes in an excellent essay on art-activism in E-Flux:

“I hope that the political function of these two divergent and even contradictory notions of aestheticization—artistic aestheticization and design aestheticization—has now became more clear. Design wants to change reality, the status quo—it wants to improve reality, to make it more attractive, better to use. Art seems to accept reality as it is, to accept the status quo. But art accepts the status quo as dysfunctional, as already failed—that is, from the revolutionary, or even postrevolutionary, perspective. Contemporary art puts our contemporaneity into art museums because it does not believe in the stability of the present conditions of our existence—to such a degree that contemporary art does not even try to improve these conditions. By defunctionalizing the status quo, art prefigures its coming revolutionary overturn. Or a new global war. Or a new global catastrophe.”

This divergence is useful, and creates a space for positive contradiction in art practices:

“But art activism cannot escape a much more radical, revolutionary tradition of the aestheticization of politics—the acceptance of one’s own failure, understood as a premonition and prefiguration of the coming failure of the status quo in its totality, leaving no room for its possible improvement or correction. The fact that contemporary art activism is caught in this contradiction is a good thing. First of all, only self-contradictory practices are true in a deeper sense of the word. And secondly, in our contemporary world, only art indicates the possibility of revolution as a radical change beyond the horizon of our present desires and expectations.”

Contrastingly, artist Francisco Brugloni, who has been formational in conceptual art utilizing found objects, has argued that public artworks are important materials in the study of political history.”The city is a space and a forge where we experienced and experimented with the world,” he said. “Our work was not about murals, or about decorating walls. We were concerned with revealing the city’s framework, mapping its interconnections, seeing what circulated it and how. We saw the city as a web that could be analyzed [through art practice]. And by analyzing it, we exposed and revealed it.”

The same could be said of the Atelier Populaire’s posters, though the protests of 1968 were quickly subdued. The Situationists splintered, workers went back to their jobs, and the de Gaulle party emerged stronger than before in the June elections. It is fitting, then, that the protesters did not want the posters to be read “as the final outcome of an experience.” They remain a tool “for finding, through contact with the masses, new levels of action both on the cultural and the political plane,” just as they were intended to.