The term “street photographer” comes with a certain set of associations: Street photographers work in public, snapping candid photos of commuters or loiterers at telling moments. They take photographs of strangers in the crowd from the perspective of a stranger themselves—an anonymous face among the anonymous masses. Perhaps the most common assumption about this class of artists is the one implied by the term: that the street photographer has a street to photograph.

Estevan Oriol is a street photographer—one of LA’s best and best known—without a street. “Look out there,” Oriol said during a recent lunchtime interview with Artillery, gesturing toward the near-deserted sidewalks outside the restaurant window. “Do you see any people down there, walking around, to photograph? I don’t walk. I drive.” Indeed, he drives in style: a 1964 Chevy Impala SS.

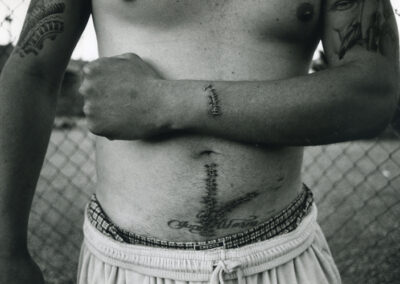

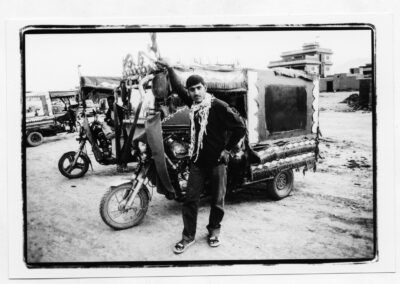

He’s also rarely met a stranger. The photos he’s best known for—of girls, gangs, guns, cars, fighters, and celebrities—portray these subjects intimately, rather than from a calculated distance. The sense in which Oriol is a street photographer is not literal but a quirk of the English language. His subjects—friends, or soon-to-be friends—are part of “the streets” in the metonymic sense of the word. They fix lowriders or lounge seductively on the cars’ luminescent hoods; they pose with guns in motel rooms or pull up their tank tops to display tattoos. They make out in the park, holding onto each other like it’s the last time.

Oriol shoots on film, in black and white, because he likes the classic feel—it erases the timestamp that digital and color photography inevitably leave behind. His work feeds both our nostalgia and our curiosity.

“Everybody wants to know about the underground cultures that they aren’t around,” he said. “Everybody wants to know about the unknown.” In the three decades of his career, Oriol’s work has become synonymous with a certain aesthetic of LA’s subcultures, especially the Chicano lowrider community. Meanwhile, he has continued to expand his life and work well beyond his hometown. He runs the clothing brand Joker with friends and collaborators Mr. Cartoon and Lucky Alvarez, and has directed movies such as L.A. Originals, a documentary from 2020 which ran up to number one on Netflix. For years, he traveled and made photographs with the rap groups Cypress Hill and House of Pain. He’s visited 56 countries. He’s made photos at every turn, the negatives of which he stores in filing cabinets in his studio before having the best made into silver gelatin prints by an elderly Iranian printer in Downtown LA, “the only guy left working in the city who can make the prints I want,” explained Oriol. “He serves you really strong, crazy tea while he makes the prints.”

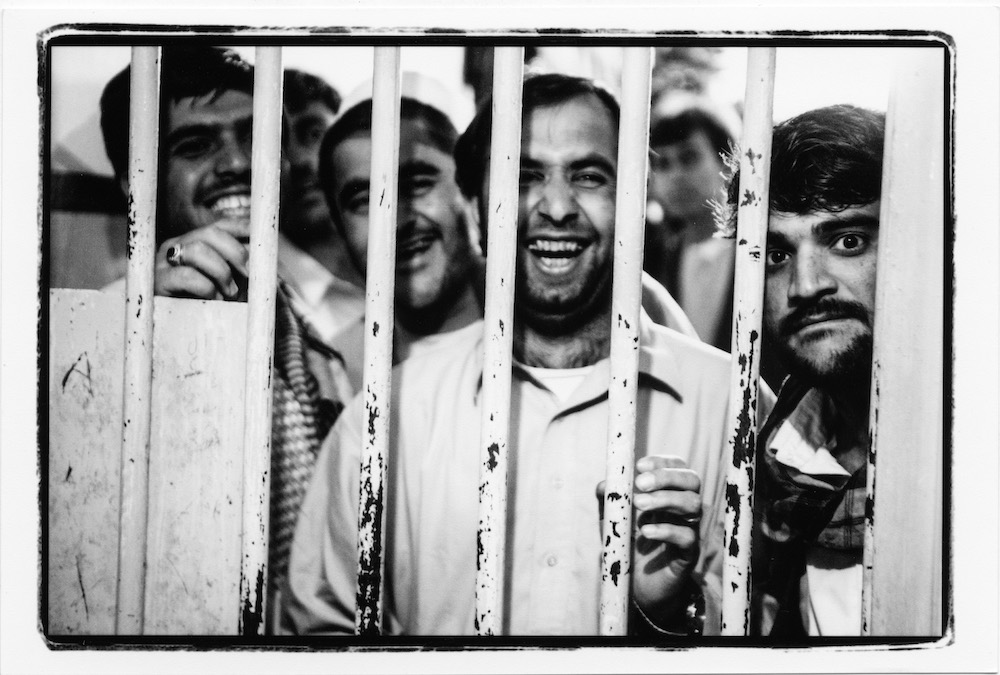

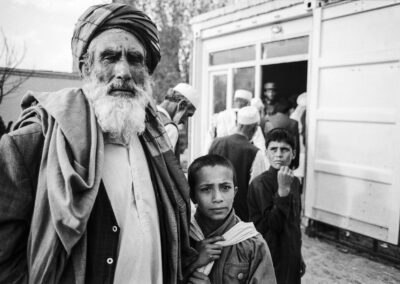

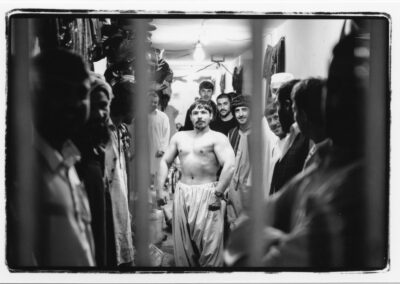

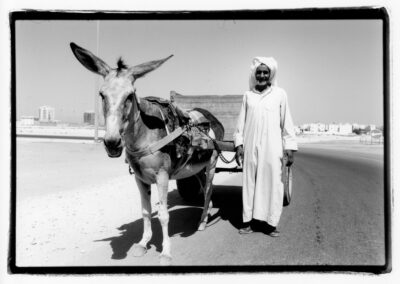

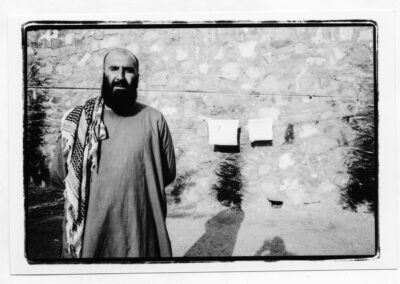

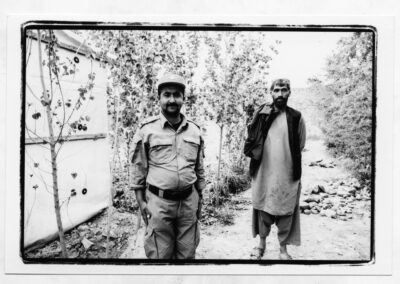

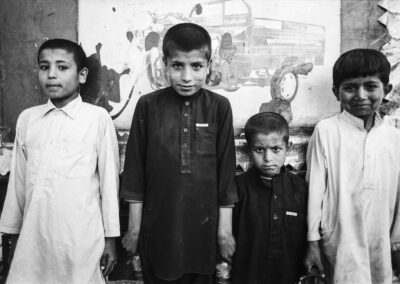

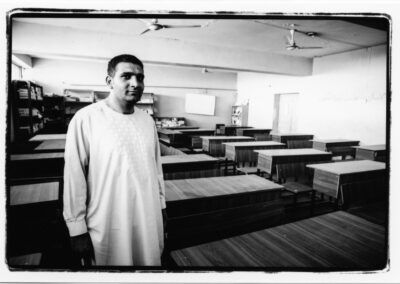

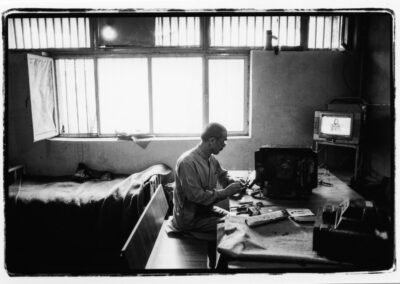

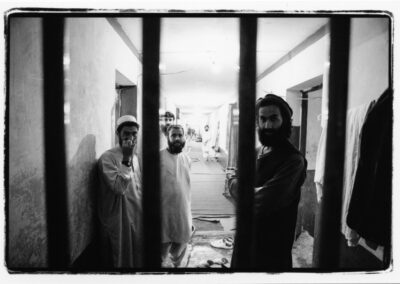

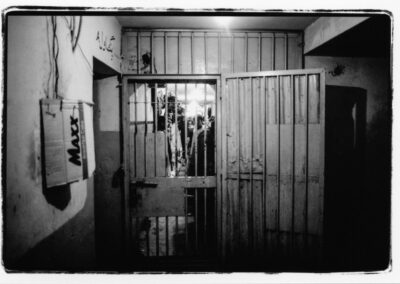

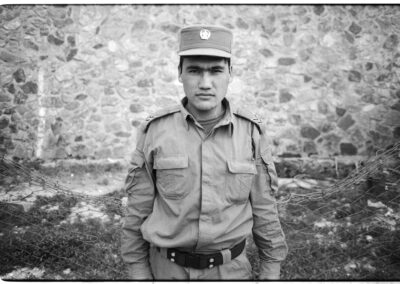

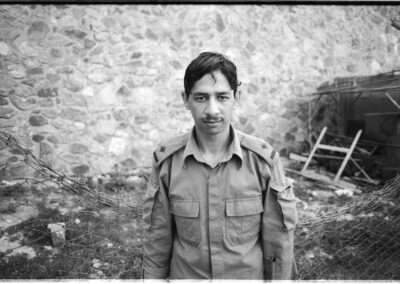

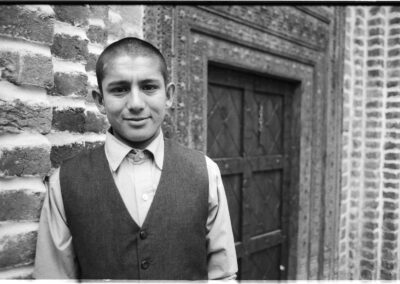

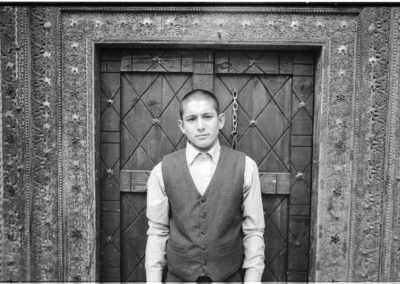

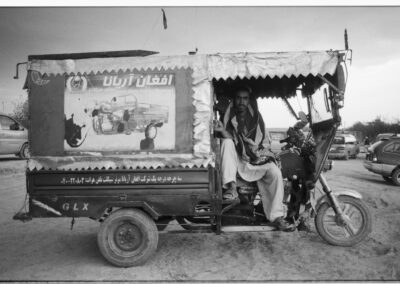

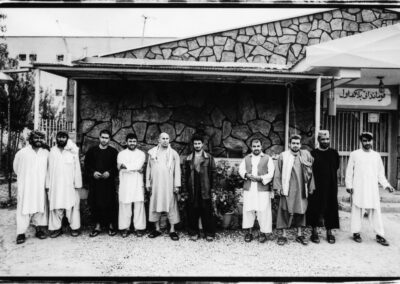

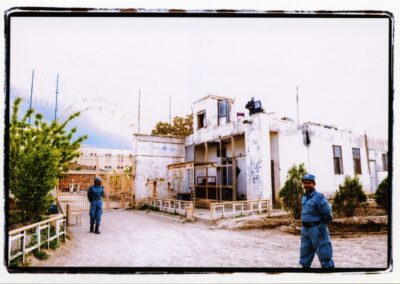

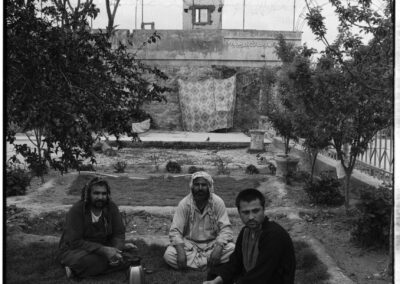

In 2016, Oriol traveled to Afghanistan. He traveled not as a photojournalist, but as part of what he called “a hangout”—he’d been in Dubai and Turkey with friends, celebrating a wealthy friend’s birthday. His host wanted to go to Afghanistan. (“He’d blindfolded himself and put a finger down on the map and decided to go to that country, which happened to be Afghanistan,” Oriol explained.) The country was not exactly open to tourists, but as Oriol put it: “If you were dumb enough to go there, they let you in.” Someone in his party found out that, among Oriol’s other subjects, he’d taken photos of prisoners in different jails around the world. They asked if he wanted to photograph a prison in Afghanistan that held Taliban prisoners. He had his reservations (“I’m an American in the middle of the war, right? Like, are these guys going to spit on me?”) but decided to go. The prisoners did not spit on him. They posed for photos. They were kind.

The photos he shot that day, of both Afghan prisoners and their visitors, are a world away from the subjects for which Oriol is best known. But his photographic eye—focused on the intimate, on beauty rather than newsworthiness or critique—produced images that reflect on this moment in America’s failed war differently than most other documents of the time and place. Seen at the distance of almost a decade, and with the knowledge of the pointlessness of the war, these images feel at once timeless and deeply fixed to an intractable history.

What is the role of memory, of nostalgia, in America’s forever wars in the Middle East? Oriol’s striking, poignant images complicate the question.