An inevitable consequence of democracy, of equality, of freedom; of systems and technologies that more evenly distribute the power to influence the world; is the production and distribution of a tremendous amount of bad art. More of us learning means more of us know art is an option, a free press means we have more to say, widespread access to paint, to press, to camera, to rentable rooms and to unsurveilled wallspace gives us more ways to say it, lack of censorship gives us a bigger potential audience, and progressive wealth distribution gives more of that audience the ability to support the art they (rightly or wrongly) love. We are and always have been, by the numbers, drowning in bad art.

Tyrannies also produce a lot of bad art, but they at least have the option of declaring it an enemy of the state. Despite this rare opportunity for tyranny to score a point in its favor, we’d also have to admit they’ve consistently flubbed it: Vladimir Putin’s favorite band is Thin Lizzy. Curation, along with military conquest, is one of the few venues for achievement open to tyrannies—but they never take the bait. What’s even the point of censorship if you’re going to inflict “Boys Are Back in Town” on an entire Moscow festival audience three decades after Phil Lynott’s dead?

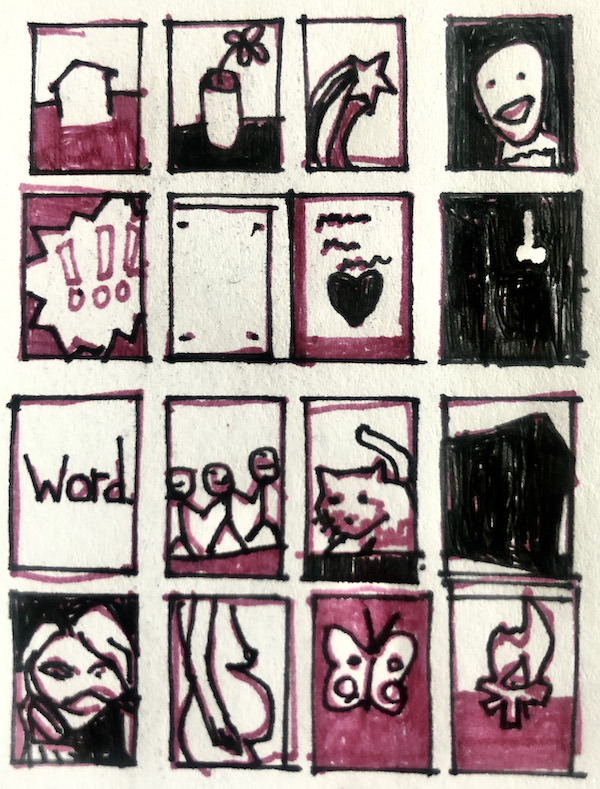

In the context of democracy-type conversations, we’re much more eager to discuss the effect of good art than the bad—we save discussing the bad art for our capitalism conversations. The cruel fact is, however, that even wholly divested of greed, we are dedicated to bad art, and we, the people, will not be diverted from making it. Bad art is as often a product of people as systems. We will always have buildings where form has shuffled dutifully after function only to realize a function ably served by 90 degree walls, whitewashed siding and what’s usually there. We will always have acid trip assemblages that never rise past quirky, we will always have high school poems that remind us how genuine and universal emotions can be very boring when they’re someone else’s, we will always have landscapes that say only that the landscape depicted would be preferable to the depiction, we will always be vulnerable to bold statements held as worthy, and paradoxically, because they contain theses it would never occur to anyone in their audience to doubt. And we will always have portraits which evoke the feeling that yep there’s a guy.

Thin Lizzy.

We will never utopianize past the possibility, indeed the necessity, of humans trying to do something worth doing and failing and then failing to notice they failed. We probably will never even utopianize past the possibility of these humans having fans. Art will be bad—let’s just accept it and study it—like bugs or the ocean.

There are more popular options for how to deal with the prevalence of the bad. Aside from seeing art as downstream of, well, everything else that could ever be wrong in the world, there’s the option to pretend the bad art has no effect, or that ignoring that effect is a good idea. (“I prefer to focus on the positive!”) If there’s one thing we keep having to be taught over and over, it’s that ignoring the effect of anything is a bad idea. Moreover: if we’re really going to keep saying the good has an effect, can we realistically say this without weighing it against the so-much-more-numerous bad?

Another option is to see the bad as simply the foot soldier of the good: good art is original, and bad art is just a harmless and less-effective echo of the good. Carrying the same insight and/or thrill… just not as much. Maybe yes but also, no: there is a particular quality to interacting with badness. A shriveling away, a disappointment with the possible—or at least with how it advertises itself. The bad sculpture doesn’t do what the good one does but less, it does the opposite: what’s expressed isn’t less expressed, it just seems less worth expressing.

We want art to touch us because there are so many petty barriers to being touched by the rich reality of whole and alien lives. When the parade of other’s loved images becomes needless and numbing to us, all other distance from humanity does as well, the death statistics and unread obituaries become as normal as anything else you scroll past. Overcoming that distance requires acknowledging all the forces that create it, including the ones that will always be there.

0 Comments