I’ve been thinking about the concept of damnatio memoriae recently. Translated as “condemnation of memory,” the term refers to a practice associated with ancient rulers who called for the erasure of their predecessors from the historical record; their likeness removed from statues, monuments, coinage and texts. It was a punishment the ancient Romans viewed as worse than death. Of course, it’s nearly impossible to obliterate someone of prominence from the historical record (Nero was subjected to the practice, and we still know about him, albeit in an unfavorable light). Still, it’s the official denial of adoration that leaves a stinging mark by removing an afterlife from otherwise immortal figures of authority.

It’s easy to see this process in the Trump administration’s recent actions such as refusing to reveal President Barack Obama’s White House portrait, and removing paintings of George W. Bush and Bill Clinton from the mansion’s grand foyer. These might seem like petty gestures (and they are). Still, they are two of many that—taken as part of a larger effort to undo President Obama’s legacy—articulate Trump’s creeping use of damnatio memoraie from on high. At the same time, Trump is rightfully concerned about how he will be remembered (or not) in the grandiose monuments he loves.

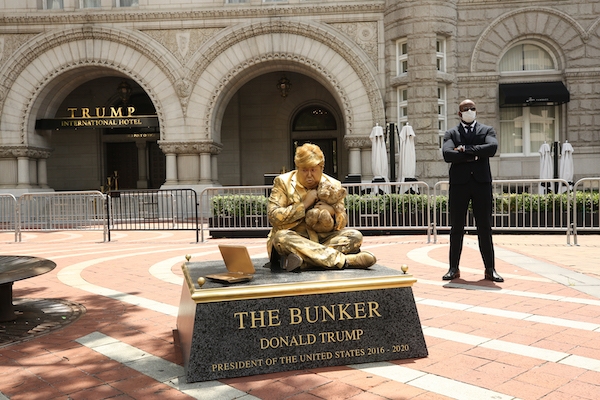

TrumpStatueInitiative, The Bunker (installation), July 17, 2020, photo by Robin Fader.

Against the backdrop of protests and actions to remove monuments to white supremacy, we are witnessing a new and beautiful kind of grassroots damnatio memoriae that is rising from the bottom up rather than the word of emperors. This correction to our monument landscape demands we not forget the evils of the past, but instead relegate the perpetrators of injustice to the reviled status they deserve. Such actions threaten those whose power stems from injustice and oppression, which is why Trump signed his executive order to “protect” American monuments; in them, he sees himself. In doing so, he revealed just how threatened he feels his legacy might be; and if past is prologue, he should be worried.

After all, Trump’s star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame has been pissed on, graffitied and jackhammered with regularity. During the 2016 U.S. Presidential campaign, the art collective Indecline placed numerous life-sized statues of a pasty, obese, naked Trump in cities across the country. In January, wooden statues of Donald and Melania were set ablaze in Slovenia, his wife’s home country. More recently, the Trump Statue Initiative installed performers painted like living statues across Washington, D.C., creating temporary monuments to some of 45’s most embarrassing moments—from hiding in the White House bunker, to public failures during the pandemic—and there are more of these monuments to come. This ongoing public critique can be viewed as a contemporaneous, perhaps pre-emptive damnation of Trump’s memory.

Unless he wins or steals the election, becoming the authoritarian he really wants to be, Trump, perhaps the worst American president in modern times, will likely suffer a popular damnatio memoriae like none ever seen in this country; a fitting punishment for such a self-absorbed man.