The whimsically titled three person exhibition “The Ocelots of Foothill Boulevard” featuring works by Mark Dion, Jessica Rath and Dana Sherwood, investigates the site of an abandoned infirmary located on land that is now a biological research field station. In the 40 some odd years since it was abandoned, the infirmary has become home to various opportunistic species and is emblematic of the kind of habitat formation fostered in the caesura of castoff human structures.

“Ocelots” orients itself to the idea of the Anthropocene, the emerging notion that radical change to Earth’s planetary systems and biomes and transformation of habitats by exotic or “invasive” species are generated by human activity.

Dion and Rath have mined the condemned structure for detritus, where in the galleries it coalesces into sculptural installation. In the act of disassembling portions of the building’s structures to generate sculptural work, the artists concomitantly disrupted the opportunistic colonization of the infirmary’s artificial biome.

Dion, known for Wunderkammer-like collections that consider the relations between artifacts and the coincident discourse of classification and cultural knowledge, has reconstructed a portion of the infirmary’s cabinetry fortified by various bits of unused medical paraphernalia and miscellaneous tools. Both his portion of the installation and Rath’s bear the marks of abandonment and reclamation from years of disuse, disasters—a fire and an earthquake—and invasive species. Dion’s Field Station (2015) exudes a feral aroma and is dotted with holes gnawed by rats, scorch marks and the remnants of smoke.

Rath’s conceptual projects address human relationships with the natural world, and her intricately researched interactions with this site resulted in poetically juxtaposed, sensuously fabricated objects transformed by her investigation. A number of Rath’s sculptural works elegantly suggest how water scarcity defines this region. Two fountains, Water Feed #1 (2016) and Water Feed #2 (2016), run continuously as if in defiance; the first, a 1950s-era water fountain juxtaposed with a vintage poster of nightfall at the Eiffel Tower, foregrounded by the fountains of Paris’ Trocadero Gardens; the second, a medical wash basin with a leg-activated control protruding beneath the basin. Honey to Brood (2016), a bronze cast of a non-native bee hive sandwiched between the infirmary windows and the plywood used to board them up, and Hive in Recess (2016) a Chromogenic print of the sandwiched hive as viewed from inside the infirmary refer to the space as transient habitat.

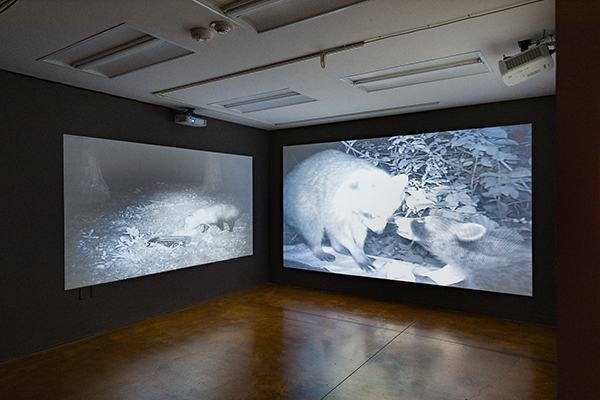

Dana Sherwood, Feral Nights Florida (raccoon, possum, fox (2015)

Courtesy of the artist , Images courtesy of Pitzer College Art Galleries, Claremont, CA, Photo: Ruben Diaz

Sherwood’s immersive video installation Feral Nights Florida (raccoon, possum, fox) (2015) and her single channel Crossing the Wild Line (Ocelot) (2015), which informs the show’s title—and contradictorily so, in that ocelots are not endemic to Southern California—provide a running soundtrack and a window into the boundary between nature and culture. But Sherwood’s work destabilizes such firm boundaries. Crossing the Wild Line (Ocelot) calls attention to the shifting ground between these arbitrary categories and underscores the cracks that nature exploits in the anthropogenic façade. Her animal “collaborators” feel familiar and take on personality—it is easy enough to anthropomorphize them, and that, perhaps, is the danger.