The surrealist impulse in art taps into not merely a human stream of consciousness, but the life and aura of everything around us, from the natural and organic to the built or crafted an inanimate. Nothing is definitively inanimate in the surrealist domain. Warhol saw acutely into the surrealism of the everyday and utilitarian commercial products, the brand aura of the stars of popular entertainment and mass-media. But this is removed only by degrees of luster or brilliance from the aura that might envelop everything around us—or at least everything within our view, or certainly within arm’s length.

To look at the drawings of Philip Rich, currently on view at the As-Is Gallery (in the West Adams neighborhood) is to be reminded of this aura, this ‘inner-life’ of objects. That has a slightly pantheistic ring to it—and there’s certainly something charmed and pixie-ish about many of these drawings—which we may be tempted to attribute to this artist’s specific formal and perceptual insights, or possibly something more psychologically sinister. Whether that quality has anything to do with the psychological and neurochemical demons that would eventually compel Rich to withdraw almost entirely from his work and life, we can only speculate. It’s a quandary we’re only beginning to unravel since Rich’s death in 2017.

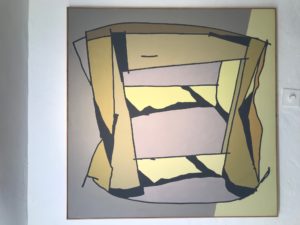

There is a painting upstairs at the Gallery (along with a few other souvenirs of Rich’s truncated artistic life), but the focus is on these drawings, made we’re told between 1965 and 1967—in other words from the moment when his brief career burned brightest to the beginning of his withdrawal. There’s a brute-Beardsley firmness and definition to these line drawings, almost a security to it. Rich draws with a firm, almost heavy hand, inking in dark voids and planes thoroughly, selective and precise in his hatchings and broken lines, or the odd fillip of a loop or spiral. We can also see the long shadow of such artists as Picabia and Schwitters (really a blur that runs from Dada and Surrealism through the peak of the Fluxus movement). Christopher Knight also suggested Ken Price and H.C. Westermann in his review (presumably with respect to an affinity with the mechanical), which seems right. (And certainly the spirit of Saul Steinberg—though without the same penchant for the rectilinear.)

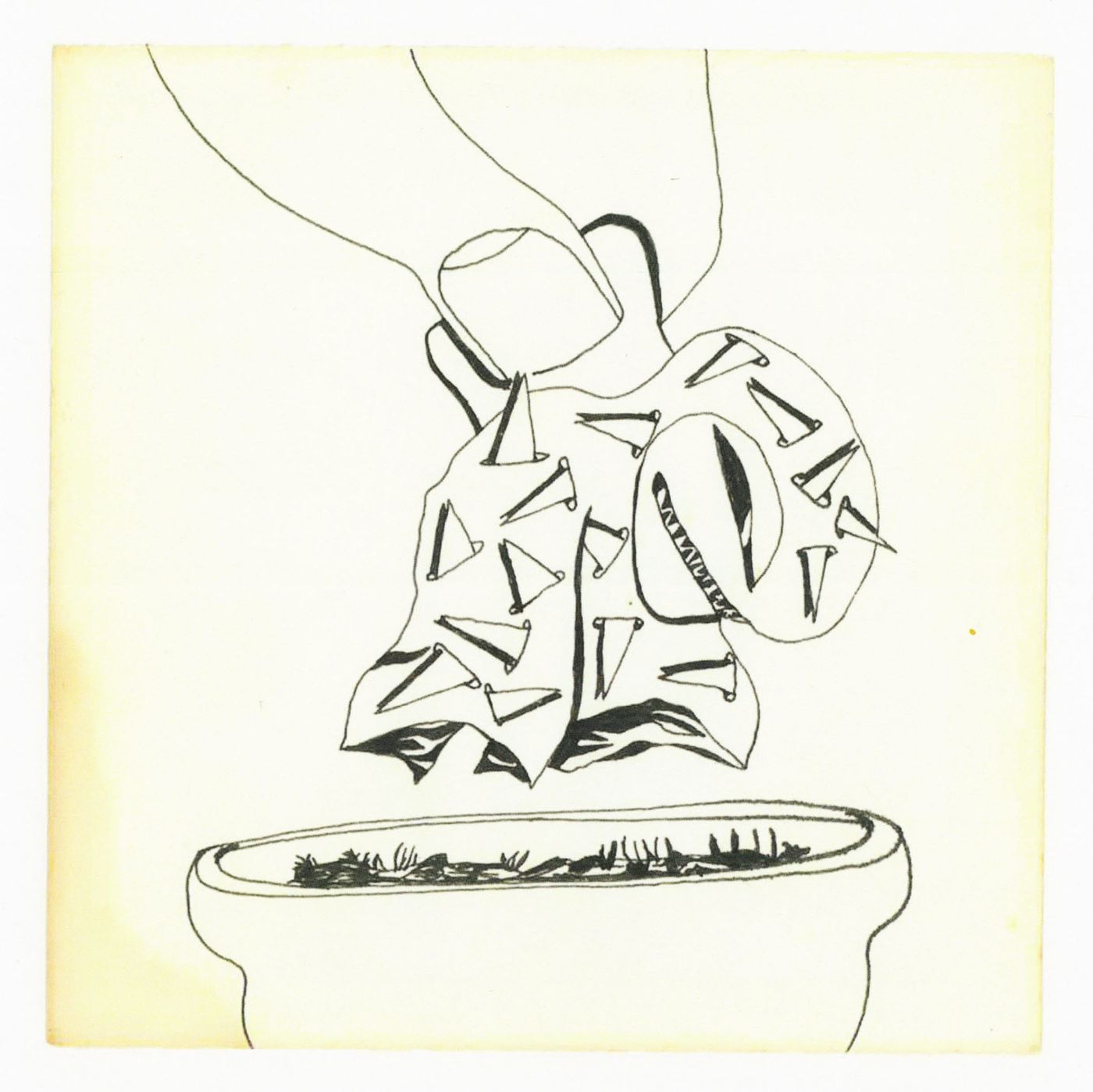

It’s almost as if Rich proceeded directly from ‘mechanical drawing’ right alongside life studies to study the inner life of machines or possibly their adaptation to a world populated by the consciousness of organic life. Consider a teetering arrangement of a faucet-like construction linked tenuously to a nasal-looking ‘tap’ construction, pivoting gyroscopically on a sketched hard(?)ware seating, uncertainly planted on a lozenge flecked plane, and dispensing an elliptical spiral of who-knows-what form of matter (or maybe just a notional plume of air), itself appearing to be mounted on another trapezoidal plane. Objects both natural and mechanical ‘act out’ a probing ballet of line and form to search and convey ‘meaning’. I’m thinking now of a drawing in which a spiky saguaro cactus with a walking cane crooked over one of its branches seems to write the word ‘Pal’ in the empty space of the paper, while another spiny form (plant? cactus? bigfoot?—albeit one planted on a pedestal) seems to push against a slender lancet sleeve or aperture of some kind.

Rich had an uncanny knack for placement and configuration of forms and the alternately logical and magical ‘illogic’ of their relationships. His caregiver told me that even as Rich had retreated from the art world, that knack never left him. He was “someone who could find some banal chotchke at a flea market, bring it home, put the right lighting on it, rearrange a few pieces of furniture around it, and give it an aura of being something very expensive.” The fancy and comedy of everyday objects (kitchen-sink comedy, if you will) inflects much of this work, but transformed and amplified by abstraction into forms both biomorphic and calligraphic or even linguistic (that Steinberg touch again). A talent for bemused observation never left him.

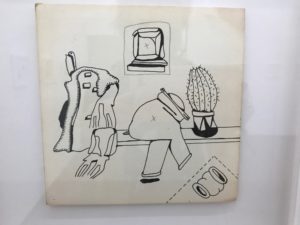

There’s also a subtle psychology at play in these drawings—a quasi-formalist sense of the simultaneous sympathy and indifference of objects. In one drawing a figure (or should we say, the shell, the container of a figure?) sits on a plank hunched over to one side (we even see a trace of the supporting hand in back of the figure), inclined towards a cactus (a recurring form), while on the other side of this bench what might be a kind of face, or a thatched house, or some configuration of aquatic life, melts and morphs into something else again. A kind of tubular form (hose? pottery?) is bracketed within dotted lines in the foreground, while in the upper quadrant, we see a rough crystalline rectangular formation not unlike one of his paintings (and specifically the one that can be seen upstairs at the gallery). Both the figure and the ‘art’ on the ‘wall’ in back of him are marked with a light ‘x’. The conundrum of an artist’s life.

There’s also a subtle psychology at play in these drawings—a quasi-formalist sense of the simultaneous sympathy and indifference of objects. In one drawing a figure (or should we say, the shell, the container of a figure?) sits on a plank hunched over to one side (we even see a trace of the supporting hand in back of the figure), inclined towards a cactus (a recurring form), while on the other side of this bench what might be a kind of face, or a thatched house, or some configuration of aquatic life, melts and morphs into something else again. A kind of tubular form (hose? pottery?) is bracketed within dotted lines in the foreground, while in the upper quadrant, we see a rough crystalline rectangular formation not unlike one of his paintings (and specifically the one that can be seen upstairs at the gallery). Both the figure and the ‘art’ on the ‘wall’ in back of him are marked with a light ‘x’. The conundrum of an artist’s life.

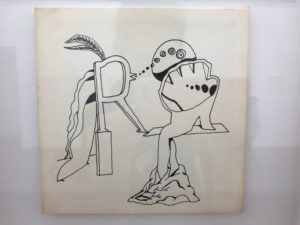

Rich is also preoccupied with the relationship of concrete objects (or their depiction or reimagination) the symbolic domain, and parallel to that the relationship of consciousness to language. In one drawing, a toothy orifice emerging on slender appendages from a primordial ooze seems to exchange smoke signals with a plumed and caparisoned letter ‘R’ lifted straight from a box of moveable type and morphed into a tweeting bird (and obviously tweeting ‘rings’ around this créature sauvage).

Rich himself was seemingly trapped in a similar Möbius strip of meaning/being and nonsense/nothingness. Once one of the Ferus Gallery’s bright lights, his star fell almost as soon as it had taken its place alongside artists like Billy Al Bengston, Lloyd Hamrol, Tony Berlant and Llyn Foulkes. However much he might have continued to suffer, given pharmacological advances since the late 1980s, he would have in all likelihood enjoyed a much more productive career even twenty years later. But the drawings give us a window on this troubled ‘soul’ beyond even the paintings’ more brutalist schema. It’s a machinery of utter madness no one entirely escapes; but these drawings locate fleeting moments of tenderness and delight we can only hope he was able to enjoy as well as share.

Philip Rich: Drawings, 1965 – 1967 closes today at the As-Is Gallery, Los Angeles.