I didn’t have the opportunity to see Carrie Mae Weems’ Guggenheim retrospective last year, but I was vaguely aware that she had taken advantage of the occasion (and location) to create something of a forum for conversation—both around the exhibited work and presumably moving forward from it. It seemed both logical and (I write this now, with some confirmation having just met the artist) characteristically generous. Weems’ work has (over the years of my encounters with it) always seemed more situational than directly confrontational. Even work with a more distinctly confrontational aspect has seemed to present itself almost neutrally—as an opportunity for thoughtful examination, consideration or reconsideration. Weems seemed in a sense to be opening up the work, the ‘situation,’ to deconstruction and reconstruction beyond the sheer mechanics of the image-making itself, to yet another level of reexamination—to probe, even cross-examine, the viewer’s apprehension and understanding.

Standing by Ceremony—Antigone

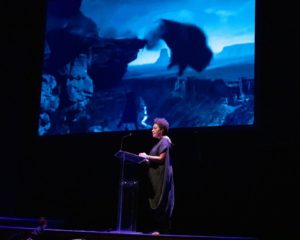

The first thing a prospective audience member might have noticed this past Friday night, the evening of Weems’ performance at the Theatre at the Ace Hotel, was that Weems had altered the title. Gone was the reference to ‘Future Perfect’. There was also the explicit shift in thematic focus—in a way, exactly the opposite of what we (usually) think about when we consider Weems’ work. The focal point here was burial—but also justice, bond, sacrifice, and sanctity. But, as in the original Antigone—Weems’ nominal inspiration here—the burial itself is undone, re-opened, or otherwise violated in various stages—a host of conflicts to be aired or exhumed.

I don’t think any of us (that is, those of us more or less familiar with Weems’ conceptual/photographic work) necessarily expected a full-blown recasting or conceptualization of the Sophoclean tragedy. But it was not hard to imagine what might have triggered it. I speak mostly for myself, but for many of us who first beheld the image of Michael Brown’s body lying face-down in a Ferguson, Missouri street, apparently abandoned for hours after a police officer shot the unarmed teen-age boy, the tragedy took on epic scope as we tried to process the horrifying actuality we were apparently still living with: after Rodney King’s police-gang beating in 1991, and the riots that followed the thugs’ acquittal in 1992; after the assassinated Martin Luther King, Jr., and the 1960s Civil Rights movement, the work of which remains unfinished (and partially undone); after Civil War and Reconstruction; after the founding of the American Republic; after…. We were all Antigone in that moment. And some of us were Creon, too.

And in 2019 we are Creon, still. (On so many levels—but I’m not going to get into that here. Weems didn’t, either; though she hinted at some of them in her texts.) I had imagined going in that the performance would be something on the order of an expansive poetic meditation, accompanied by staging or art direction that encompassed Weems’ photography and video (or possibly the stated ‘situations’ we might imagine from it) that have been at the core of her practice. And it was—indeed more conceptually abstract that most of her more familiar work. But the meditation was what took over; and I think this was Weems’ intention all along.

This was not a retrospective; and it wasn’t a forum or symposium, either, as we might have anticipated in the wake of Past Tense/Future Perfect. This was a full stop—not dissimilar in its own way from many recent artistic expressions in film, music and theatre, as well as the visual fine arts. CAP-UCLA’s notes placed Weems’ initial impulses for the work in the context of another live performance work she performed in 2016, Grace Notes, and I’m reasonably certain the work evolved from a number of disparate sources, ideas and influences. But Weems is acknowledging something much larger here in the way we perceive the shape of contemporary reality. It is a shift of mythic foundational dimension; ‘Antigone’ is simply another expression of its shape and offers us another lens through which to view its tragic scope.

Exhumation and Atonement

Notwithstanding a scope that necessarily encompassed the cosmic or divine, I’m not sure why Weems and her team felt compelled to augment her performance with additional texts by her co-performer Carl Hancock Rux, unless she felt the audience needed to be warmed up to the notion of a quasi-religious or spiritual experience, rite or ritual. Rux’s text, rendered in a kind of blank verse, took some pains to cover all bases from the notionally monotheistic to the agnostic; but it was scarcely necessary. The photographic and video backdrops were sufficiently oceanic to both open and empty our minds to whatever we might be asked to receive. (Weems understands the conditions essential to a truly meditative experience.) It was the ‘communion’ before the ‘offertory’—to draw a parallel to Roman Catholic liturgy. There would be no ‘gospel’. Whose ‘gospel’ could that even be? The point being that we would reach no clear or pre-set plot points in this meditation. This was an evening in which conflict and contradiction would be held in suspense. We had the observable and verifiable facts and their aftermath before us. What or how the trauma had been sustained might never be clearly established. We were here to confront the actuality and aftermath and come to some terms with it.

Nor would there be ‘grace’, unless we understood that to be in its least expansive, most reserved sense—of dispensation, reciprocal accommodation, stipulated entente, clemency, mercy—above all, mercy. After the first, largely superfluous preamble, the evening could be seen as one sustained ‘Kyrie’—yet an unapologetically secular one, in which the officiants felt no reservation in posing an existential question: ‘Here we are again … (as the first singer, entering from an aisle and crossing the stage intoned) … how did we get here?’

Nor would there be ‘grace’, unless we understood that to be in its least expansive, most reserved sense—of dispensation, reciprocal accommodation, stipulated entente, clemency, mercy—above all, mercy. After the first, largely superfluous preamble, the evening could be seen as one sustained ‘Kyrie’—yet an unapologetically secular one, in which the officiants felt no reservation in posing an existential question: ‘Here we are again … (as the first singer, entering from an aisle and crossing the stage intoned) … how did we get here?’

The video imagery was shifting, too, as the singers (serene and very strong) crossed the stage one after another and intoned the same undulant lines—a long sine-cosine wave of acknowledgment: swirls of migrating geese or birds that seemed to arc and spiral portentously as they moved through the gray skies; charging herds of buffalo or bison hurtling themselves off cliffs. While the imagery clearly announced we were at a precipice, Weems, entering stage left and walking directly to the lectern, seemed to convey a sense of calm patient deliberation. She was here to observe, bear witness no less than her audience. She began her remarks almost tentatively, as if to underscore the implicit understanding: we all knew something was going on lately in this country (no need to add, ‘and the rest of the world’): “an extraordinary transition” that (tentatively again) we might “help us navigate.” It was a proposition she was putting to us, and in the most direct, quotidian, matter-of-fact terms: referencing “shifting demographics,” and “disenfranchised white men” as well as “disaffected black men”; a key difference being that the disaffected black men were also the “dying black men.” Yet amid evident “resistance,” the violence was “escalating.” Here she crossed the threshold into the theatrical crucible she cautioned “is not a play.” And even here she interjected a factual note—that violence against black men had actually increased during the presidency of Barack Obama, and began dropping almost as soon as he left office.

It was as if Weems (along with the rest of us) had stumbled into this mythic, tragic terrain like those mortals compelled for one purpose or another to visit the underworlds of those classical and mythological texts. How was it possible that here we were again? Antigone would end entombed and ready to die; “but I want to live!” Yet ‘here we were again,’ returned to this domain of moral and ethical conflict—with moral imperatives in conflict with ethical norms, or alternatively, the law as written, understood, and enforced. Sophocles squares off these conflicting moral and ethical imperatives as the crux of his tragedy. And within the ineluctable tragedy of these catastrophic collisions Sophocles also articulates the dynamic of underlying motive and intention—“whether the offense was committed rightly or wrongfully.”

Unburied Dead and Unending Desecrations

“Rightly or wrongly, challenging … the laws of the state who refused to recognize, rightly or wrongly …. Rightly or wrongly, it is decreed…. Responding to a higher law, rightly or wrongly….” Weems would carry this suspension of judgment into the next section of the text—playing out the tragedy in microcosm as it’s lived on American streets. But in that moment it framed the character of the evening as an evening of atonement and remembrance. This was the ‘Kol Nidre’—the preliminary disavowals that would precede the litanies and petitions of the rest of the evening. And they had the character of a Yom Kippur service—though, just as there could be no ‘gospel’, there would be no Jonah/Haftarah here, either. This was about mourning, not necessarily forgiveness, much less redemption. To hear Weems set out the perfunctory details of such a hypothetical placid evening become an obscene murder under color of law was devastating. “Imagine: one evening you’re out strolling with your wife, a friend… a police car speeds by, its red strobe flashing… For reasons unknown… For no apparent reason… shots are fired… for no apparent reason…”And then we began to hear the names, conscious that the 200 might easily be 200 million—and we felt, as Weems circled back to the beginning again, “the West was trembling…. It was the Autumn of the Patriarch….”

The names flashed by on the screens; but although I know from a still photo of the event that Michael Brown’s name appeared, I can remember neither seeing it, nor hearing Weems reciting it. I have to assume I somehow blocked it. (I did clearly hear Sandra Bland’s name; and her death had had a similar impact at the time of the first news accounts.) The power of those initial reports and images endures much as Sophocles’ tragedy.

It was not an evening from which we could take joy or even hope. That function for all practical purposes was taken up by Weems’ musical team (Eddie Allen, Calvin Jones, Adam Klipple, Tony Lewis and Jay Rodriguez), which soared under the direction of Craig Harris, with some beautifully elegiac jazz material, both original and adapted (Jill Scott; plus there was a gorgeous setting of Gershwin’s “My Man’s Gone Now” (from Porgy and Bess)) as the show moved towards its closing moments). But if we’ve already passed the ‘autumn of the Patriarch,’ the winter of hell is not far off. Weems’ rite of atonement and remembrance was also one of admonishment. We’ve “heard the shot” again and again. And there can be no further excuse for “deceiv[ing] [our]selves,” Weems reminds us. The ethical and moral implications are plain. We continue to bear witness and resist because we want to live.

It was not an evening from which we could take joy or even hope. That function for all practical purposes was taken up by Weems’ musical team (Eddie Allen, Calvin Jones, Adam Klipple, Tony Lewis and Jay Rodriguez), which soared under the direction of Craig Harris, with some beautifully elegiac jazz material, both original and adapted (Jill Scott; plus there was a gorgeous setting of Gershwin’s “My Man’s Gone Now” (from Porgy and Bess)) as the show moved towards its closing moments). But if we’ve already passed the ‘autumn of the Patriarch,’ the winter of hell is not far off. Weems’ rite of atonement and remembrance was also one of admonishment. We’ve “heard the shot” again and again. And there can be no further excuse for “deceiv[ing] [our]selves,” Weems reminds us. The ethical and moral implications are plain. We continue to bear witness and resist because we want to live.